Discover Ichi-go Ichi‑e, the Japanese Art of Savoring Every Moment

Each culture has its own sayings about the uniqueness and transience of the present moment. In recent years, the English-speakers have often found themselves reminded, through the expression “YOLO,” that they only live once. (The question of whether that should really be “YLOO,” or “You Live Only Once,” we put aside for the time being.) In Japan, unsurprisingly, one sometimes hears a much more venerable equivalent: “i**chi-go ichi‑e,” which some readers acquainted with the Japanese lan…

Discover Ichi-go Ichi‑e, the Japanese Art of Savoring Every Moment

Each culture has its own sayings about the uniqueness and transience of the present moment. In recent years, the English-speakers have often found themselves reminded, through the expression “YOLO,” that they only live once. (The question of whether that should really be “YLOO,” or “You Live Only Once,” we put aside for the time being.) In Japan, unsurprisingly, one sometimes hears a much more venerable equivalent: “i**chi-go ichi‑e,” which some readers acquainted with the Japanese language should be assured has nothing to do with strawberries, ichigo. Rather, the saying’s underlying Chinese characters (一期一会) can be translated as “one time, one meeting.”

The Buddhistically inflected “i**chi-go ichi‑e” is just one in the vast library of yojijukugo, highly condensed aphoristic expressions written with just four characters. (Other countries with Chinese-influenced languages have their versions, including sajaseongeo in Korea and *chéngyǔ *in China itself.) It descends, as the story goes, from a slightly longer saying favored by the sixteenth-century tea master Sen no Rikyū, “ichi-go ni ichi-do” (一期に一度).

One must pay respects to the host of a tea ceremony because the meeting would only ever occur once — which, of course, it would, even if the ceremony was a regularly scheduled event. For we never, to borrow an ancient Greek take on this whole subject, step into the same river twice; no two events, separated in time, can ever truly be identical.

One implication, as noted in the explanatory videos above from the BBC and Einzelgänger, is that we should savor whatever moment we happen to find ourselves in, however imperfect, because we won’t get a second chance to do so. And if it offers little or nothing to enjoy, we can find solace in the fact that its particular displeasure, too, can never revisit us. With the past gone and the future never guaranteed, the present moment, in any case, is the only time that actually exists for us, so we’d better make ourselves comfortable within it. Though these ideas have perhaps found their most elegant and memorable expression in Japan, they’re hardly considered exclusive cultural property there. The Japanese title of Forrest Gump, after all, was Foresuto Ganpu: Ichi-go Ichi‑e.

Related Content:

Wabi-Sabi: A Short Film on the Beauty of Traditional Japan

Memento Mori: How Smiling Skeletons Have Reminded Us to Live Fully Since Ancient Times

Based in Seoul, ColinMarshall writes and broadcas**ts on cities, language, and culture. He’s the author of the newsletter Books on Cities* as well as the books 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea) and Korean Newtro.* Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Using a Tape Recorder for the First Time, Reads from The Hobbit for 30 Minutes (1952)

in * Audio Books, Literature * | January 5th, 2026

Having not revisited The Hobbit in some time, I’ve felt the familiar pull—shared by many readers—to return to Tolkien’s fairy-tale novel itself. It was my first exposure to Tolkien, and the perfect book for a young reader ready to dive into moral complexity and a fully-realized fictional world.

And what better guide could there be through *The Hobbit *than Tolkien himself, reading (above) from the 1937 work? In this 1952 recording in two parts (part 2 is below), the venerable fantasist and scholar reads from his own work for the first time on tape.

Tolkien begins with a passage that first describes the creature Gollum; listening to this description again, I am struck by how much differently I imagined him when I first read the book. The Gollum of The Hobbit seems somehow hoarier and more monstrous than many later visual interpretations. This is a minor point and not a criticism, but perhaps a comment on how necessary it is to return to the source of a mythic world as rich as Tolkien’s, even, or especially, when it’s been so well-realized in other media. No one, after all, knows Middle Earth better than its creator.

These readings were part of a much longer recording session, during which Tolkien also read (and sang!) extensively from The Lord of the Rings. A YouTube user has collected, in several parts, a radio broadcast of that full session, and it’s certainly worth your time to listen to it all the way through. It’s also worth knowing the neat context of the recording. Here’s the text that accompanies the video on YouTube:

When Tolkien visited a friend in August of 1952 to retrieve a manuscript of The Lord of the Rings, he was shown a “tape recorder”. Having never seen one before, he asked how it worked and was then delighted to have his voice recorded and hear himself played back for the first time. His friend then asked him to read from The Hobbit, and Tolkien did so in this one incredible take.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2012.

Related Content

J. R. R. Tolkien Admitted to Disliking Dune “With Some Intensity” (1966)

J. R. R. Tolkien Reads from The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings & Other Works

J.R.R. Tolkien Snubs a German Publisher Asking for Proof of His “Aryan Descent” (1938)

Josh Jones* is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. *

When Two Filmmakers Make the Same Movie — and One of Them Is Werner Herzog

in * Film, Nature * | January 2nd, 2026

In 1991, the French husband-and-wife volcanologist-filmmaker team Maurice and Katia Krafft were killed by the flow of ash from the eruption of Mount Unzen in Nagasaki. Inexplicably, Werner Herzog didn’t get around to making a film about them for more than 30 years. These would seem to be ideal subjects for the documentary half of his career, a large portion of which he’s spent on portraits of eccentric, romantic, often foolhardy, and more than occasionally ill-fated individuals who pit themselves, or in any case find themselves pitted, against the raw elements of nature. Their couplehood makes the Kraffts a slight exception in that lineup, but it also makes them even less resistible to a more conventional documentarian — not that a documentarian could get much less conventional than Herzog.

Hence, perhaps, the appearance of two entirely separate documentaries on the Kraffts in the same year, 2022: Herzog’s The Fire Within, and Sara Dosa’s Fire of Love. The Like Stories of Old video above performs a direct comparison of the two films, both of which make heavy use of the volcano footage shot by the Kraffts themselves.

Herzog assembles it into wordless, operatically scored, and sometimes quite long sequences, intensifying their quality of the sublime, which we feel in that aesthetic zone where awe of beauty and fear of existential annihilation overlap completely. These do nothing to advance a narrative, but everything to put forth what Herzog has often referred to in interviews as a sense of “ecstatic truth,” a distillation of reality that cannot be captured by any conventional documentary means.

The video’s host Tom van der Linden describes Fire of Love as “much more fast-paced. Images come and go so quickly that they don’t really have a chance to reveal that strange, secret beauty, to take the spotlight with their own mysterious stardom. Instead, they feel subservient to whatever predetermined emotion the narrative wants you to experience,” as if the director is giving you orders: “Be in awe. Feel the romance. And now the comedy.” That hardly suggests incompetence on the part of Dosa and her collaborators, or any deficiency in her highly acclaimed film. But it does give us a sense of what becomes wearying about the techniques of mainstream cinema in general, fictional, or nonfictional. The truth is that Werner Herzog may be uniquely well placed to appreciate not just the fearsomely enrapturing object of the Kraffts’ obsession, but also the driving passion, and flashes of ridiculousness, in the Kraffts themselves — who were, after all, fellow soldiers of cinema.

Related Content:

An Introduction to the Painting of Caspar David Friedrich, Romanticism & the Sublime

Underwater Volcanic Eruption Witnessed for the First Time

Werner Herzog Discovers the Ecstasy of Skateboarding: “That’s Kind of My People”

Based in Seoul, ColinMarshall writes and broadcas**ts on cities, language, and culture. He’s the author of the newsletter Books on Cities* as well as the books 한국 요약 금지 (No Summarizing Korea) and Korean Newtro.* Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

The Birth of Espresso: The Story Behind the Coffee Shots That Fuel Modern Life

in * Food & Drink, History * | January 2nd, 2026

Espresso is neither bean nor roast.

It is a method of pressurized coffee brewing that ensures speedy delivery, and it has birthed a whole culture.

Americans may be accustomed to camping out in cafes with their laptops for hours, but Italian coffee bars are fast-paced environments where customers buzz in for a quick pick-me-up, then head right back out, no seat required.

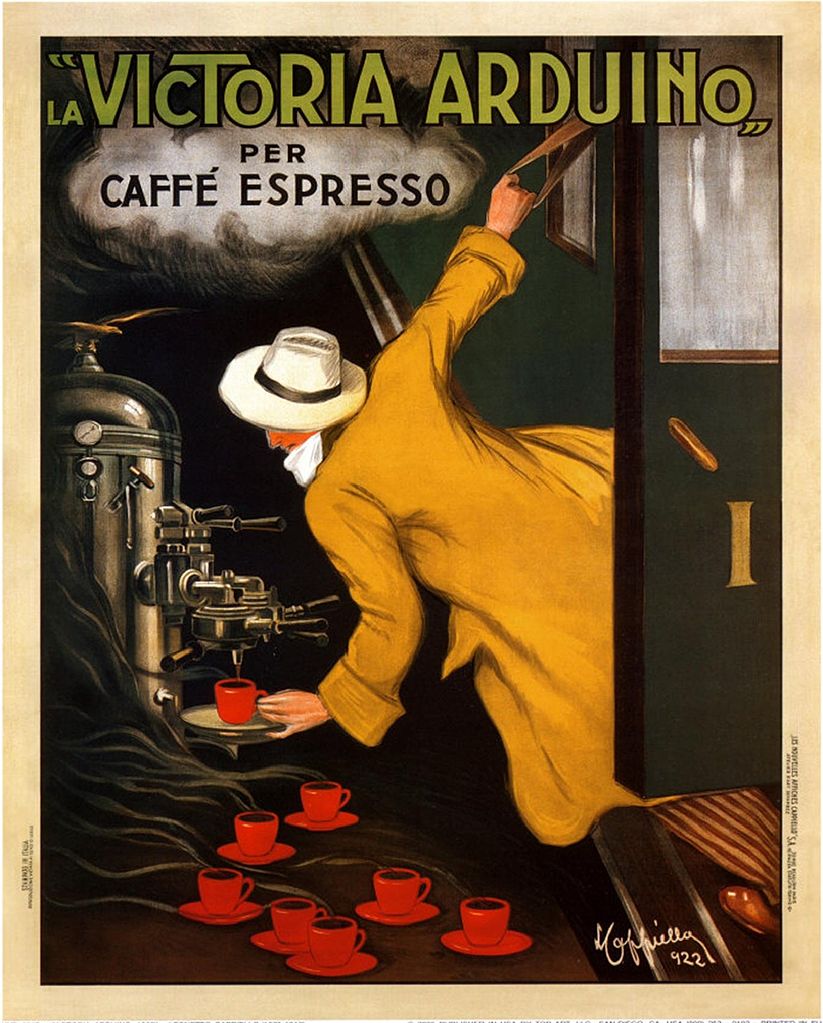

It’s the sort of efficiency the Father of the Modern Advertising Poster, Leonetto Cappiello, alluded to in his famous 1922 image for the Victoria Arduino machine (below).

Let 21st-century coffee aficionados cultivate their Zen-like patience with slow pourovers. A hundred years ago, the goal was a quality product that the successful businessperson could enjoy without breaking stride.

As coffee expert James Hoffmann, author of The World Atlas of Coffee points out in the above video, the Steam Age was on the way out, but Cappiello’s image is “absolutely leveraging the idea that steam equals speed.”

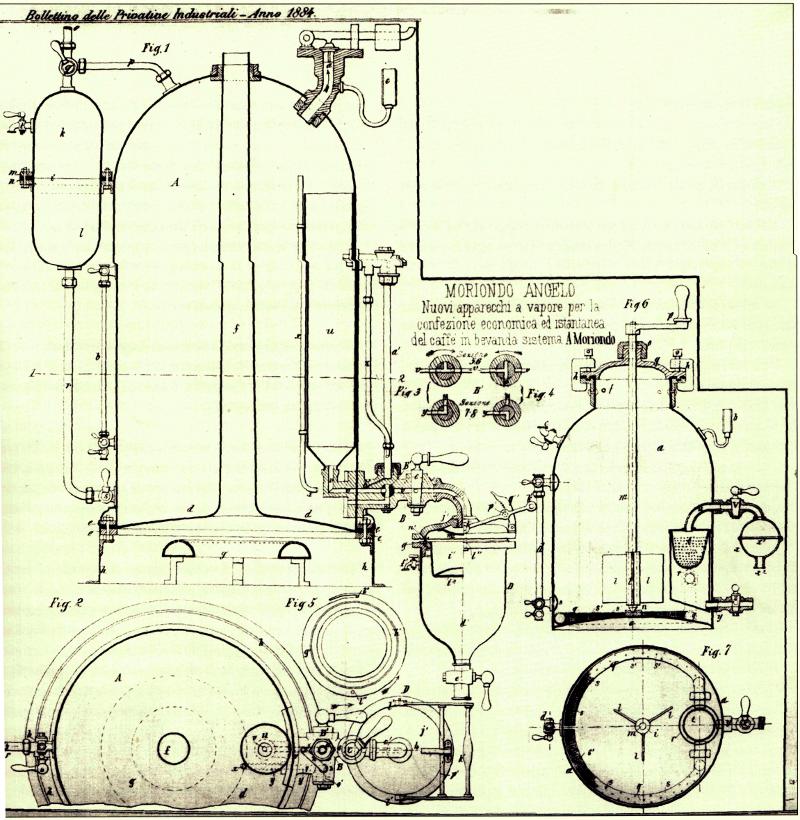

That had been the goal since 1884, when inventor Angelo Moriondo patented the first espresso machine (see below).

The bulk brewer caused a stir at the Turin General Exposition. Speed wise, it was a great improvement over the old method, in which individual cups were brewed in the Turkish style, requiring five minutes per order.

This “new steam machinery for the economic and instantaneous confection of coffee beverage” featured a gas or wood burner at the bottom of an upright boiler, and two sight glasses that the operator could monitor to get a feel for when to open the various taps, to yield a large quantity of filtered coffee. It was fast, but demanded some skill on the part of its human operator.

As Jimmy Stamp explains in a Smithsonian article on the history of the espresso machine, there were also a few bugs to work out.

Early machines’ hand-operated pressure valves posed a risk to workers, and the coffee itself had a burnt taste.

Milanese café owner Achille Gaggia cracked the code after WWII, with a small, steamless lever-driven machine that upped the pressure to produce the concentrated brew that is** **what we now think of as espresso.

Stamp describes how Gaggia’s machine also standardized the size of the espresso, giving rise to some now-familiar coffeehouse vocabulary:

The cylinder on lever groups could only hold an ounce of water, limiting the volume that could be used to prepare an espresso. With the lever machines also came some new jargon: baristas operating Gaggia’s spring-loaded levers coined the term “pulling a shot” of espresso. But perhaps most importantly, with the invention of the high-pressure lever machine came the discovery of crema – the foam floating over the coffee liquid that is the defining characteristic of a quality espresso. A historical anecdote claims that early consumers were dubious of this “scum” floating over their coffee until Gaggia began referring to it as “caffe creme,“ suggesting that the coffee was of such quality that it produced its own creme.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2021.

Related Content:

Coffee Entrepreneur Renato Bialetti Gets Buried in the Espresso Maker He Made Famous

The Life & Death of an Espresso Shot in Super Slow Motion

*Ayun Halliday *is an author, illustrator, and theater maker in NYC.

What’s Entering the Public Domain in 2026: Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, All Quiet on the Western Front, Betty Boop & More

in * Books, Comics/Cartoons, Film, Law, Music * | January 1st, 2026

Though it isn’t the kind of thing one hears discussed every day, serious Disney fans do tend to know that Goofy’s original name was Dippy Dawg. But how many of the non-obsessive know that Mickey’s faithful pet Pluto was first called Rover? (We pass over in dignified silence the quasi-philosophical question of why the former dog is humanoid and the latter isn’t.) It is Rover, as distinct from Pluto, who passes into the public domain this new year, one of a cast of now-liberated characters including Blondie and Dagwood as well as Betty Boop — who, upon making her debut in Fleischer Studios’ Dizzy Dishes of 1930, has a somewhat canoid appearance herself. You can see them all in the video above from Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, with much more information available in their blog post marking this year’s “Public Domain Day.”

The year 1930, write the Center’s Jennifer Jenkins and James Boyle, was one “of detectives, jazz, speakeasies, and iconic characters stepping onto the cultural stage — many of whom have been locked behind copyright for nearly a century.”

Novels that come available this year include William Faulkner’s *As I Lay Dying, *Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, and Agatha Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage; among the films are Lewis Milestone’s Best Picture-winning All Quiet on the Western Front, Victor Heerman’s Marx Brothers picture Animal Crackers, and Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s L’Âge d’Or. In music, compositions like “I Got Rhythm” and “Embraceable You” by the Gershwin Brothers as well as recordings like “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” by Marian Anderson and “Sweet Georgia Brown” by Ben Bernie and His Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra have also, at long last, gone public.

Reflection on some of these works themselves suggests something about the importance of the public domain. With the title of Cakes and Ale, another book in this year’s crop, Somerset Maugham makes reference to “a classic public domain work, in this case Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night”; so, for that matter, does Faulkner, given that the line “as I lay dying” comes from the Odyssey. “To tell new stories, we draw from older ones,” write Jenkins and Boyle. “One work of art inspires another — that is how the public domain feeds creativity.” Today, we’re free to take explicit inspiration for our own work from Nancy Drew, “Just a Gigolo,” Blondie, Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow, Hitchcock’s Murder!, and much else besides. And by all means use Rover, but if you also want to bring in Dippy Dawg, you’re going to have to wait until 2028.

Related Content:

The Harlem Jazz Singer Who Inspired Betty Boop: Meet the Original Boop-Oop-a-Doop, “Baby Esther”

Cartoonists Draw Their Famous Cartoon Characters While Blindfolded (1947)

Vintage Audio: William Faulkner Reads From As I Lay Dying

16 Free Hitchcock Movies Online

Based in Seoul, ColinMarshall writes and broadcas**ts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities* and the book *The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Woody Guthrie Creates a Doodle-Filled List of 33 New Year’s Resolutions (1943): Beat Fascism, Write a Song a Day, and Keep the Hoping Machine Running

in * Uncategorized * | January 1st, 2026

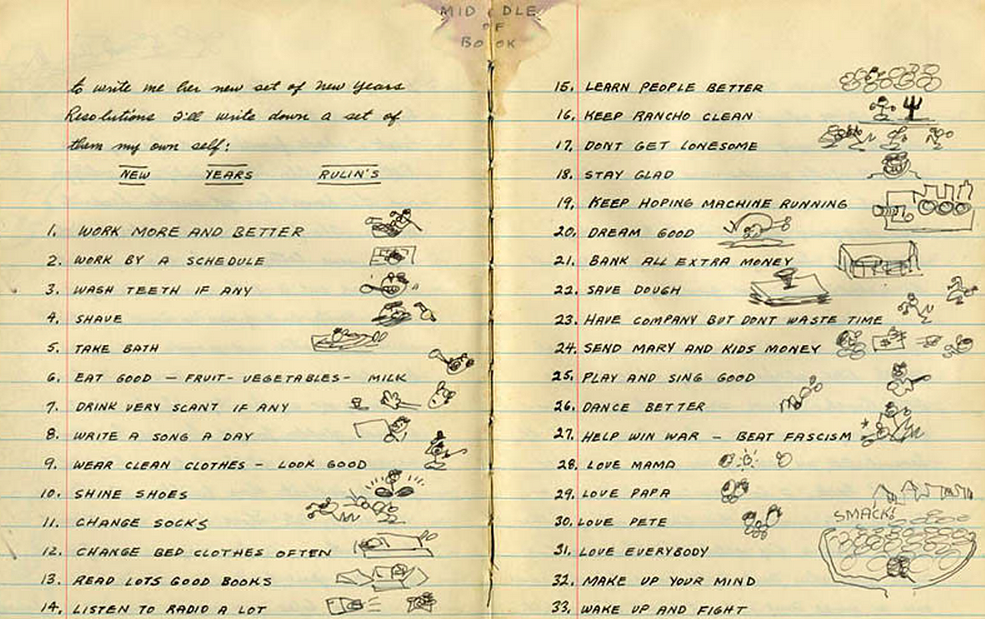

On January 1, 1943, the American folk music legend Woody Guthrie jotted in his journal a list of 33 “New Years Rulin’s.” Nowadays, we’d call them New Year’s Resolutions. Adorned by doodles, the list is down to earth by any measure. Family, song, taking a political stand, personal hygiene—they’re the values or aspirations that top his list. You can click the image above to view the list in a larger format. Below, we have provided a transcript of Guthrie’s Rulin’s.

1. Work more and better 2. Work by a schedule 3. Wash teeth if any 4. Shave 5. Take bath 6. Eat good — fruit — vegetables — milk 7. Drink very scant if any 8. Write a song a day 9. Wear clean clothes — look good 10. Shine shoes 11. Change socks 12. Change bed cloths often 13. Read lots good books 14. Listen to radio a lot 15. Learn people better 16. Keep rancho clean 17. Dont get lonesome 18. Stay glad 19. Keep hoping machine running 20. Dream good 21. Bank all extra money 22. Save dough 23. Have company but dont waste time 24. Send Mary and kids money 25. Play and sing good 26. Dance better 27. Help win war — beat fascism 28. Love mama 29. Love papa 30. Love Pete 31. Love everybody 32. Make up your mind 33. Wake up and fight

We wish you all a happy 2018.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!**

Note: This fine list originally appeared on our site back in 2014.

Related Content:

Marilyn Monroe’s Go-Getter List of New Year’s Resolutions (1955)

Antonio Gramsci Writes a Column, “I Hate New Year’s Day” (January 1, 1916)

The Top 10 New Year’s Resolutions Read by Bob Dylan

The Mystery of How a Samurai Ended up in 17th Century Venice

in * History * | December 31st, 2025

It wouldn’t surprise us to come across a Japanese person in Venice. Indeed, given the global touristic appeal of the place, we could hardly imagine a day there without a visitor from the Land of the Rising Sun. But things were different in 1873, just five years after the end of the *sakoku *policy that all but closed Japan to the world for two and a half centuries. On a mission to research the modern ways of the newly accessible outside world, a Japanese delegation arrived in Venice and found in the state archives two letters written in Latin by one of their countrymen, dated 1615 and 1616. Its author seemed to have been an emissary of Ōtomo Sōrin, a feudal lord who converted to Christianity and once sent a mission of four teenagers to meet the Pope in Rome — a mission that took place earlier, in 1586.

So who could this undocumented Japanese traveler in the fifteen-tens have been? That question lies at the heart of the story told by Evan “Nerdwriter” Puschak in his new video above. The letter’s signature of Hasekura Rokemon would’ve constituted a major clue, but the name seems not to have rung a bell with anyone at the time.

“In 1873, there was likely no one on planet Earth who knew why Hasekura Rokemon was in Venice in 1615,” says Puschak. The reasons have to do with the arrival of Christianity in Japan — or at least the arrival of the first major Jesuit missionary — in 1549. Not every ruler looked kindly on their work, and especially not Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who ordered them removed from the country in 1587 and later had 26 Catholics crucified in Nagasaki.

Hideyoshi was succeeded by the more tolerant Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), during whose rule the Japanese-speaking Franciscan friar Luis Sotelo arrived in Japan. Over the ensuing decade, he worked not just to spread his faith but also to build hospitals, one of which successfully treated a European concubine of the feudal lord Date Masamune. The two men got on, realizing the mutual benefit their relationship could bring: perhaps Sotelo could found a new diocese in Date’s northern territory, and perhaps Date could establish links with the Spanish empire. In order to accomplish the latter, he had a ship built and a team assembled for a mission to Europe, including Sotelo himself. He sent with them a loyal retainer, a samurai by the name of Hasekura Rokemon — or to use his full name, Hasekura Rokuemon Tsunenaga, previously featured here on Open Culture for his meeting with the pope and adoption of Roman citizenship. He may have been Japanese, but a mere tourist he certainly wasn’t.

Related Content:

The 17th Century Japanese Samurai Who Sailed to Europe, Met the Pope & Became a Roman Citizen

21 Rules for Living from Miyamoto Musashi, Japan’s Samurai Philosopher (1584–1645)

A Mischievous Samurai Describes His Rough-and-Tumble Life in 19th Century Japan

How to Be a Samurai: A 17th Century Code for Life & War

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Meet Yasuke, Japan’s First Black Samurai Warrior

Based in Seoul, ColinMarshall writes and broadcas**ts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities* and the book *The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

J. R. R. Tolkien Admitted to Disliking Dune “With Some Intensity” (1966)

in * Books, Literature * | December 30th, 2025

One can easily imagine a reader enjoying both The Lord of the Rings and Dune. Both of those works of epic fantasy were published in the form of a series of long novels beginning in the mid-twentieth century; both create elaborate worlds of their own, right down to details of ecology and language; both seriously (and these days, unfashionably) concern themselves with the theme of what constitutes heroic action; both have even inspired multiple big-budget Hollywood spectacles. The reader equally dedicated to the work of J. R. R. Tolkien and Frank Herbert turns out to be a more elusive creature than we may expect, but perhaps that shouldn’t surprise us, given Tolkien’s own attitude toward Dune.

“It is impossible for an author still writing to be fair to another author working along the same lines,” Tolkien wrote in 1966 to a fan who’d sent him a copy of Herbert’s book, which had come out the year before. “In fact I dislike DUNE with some intensity, and in that unfortunate case it is much the best and fairest to another author to keep silent and refuse to comment.”

That lack of elaboration has, if anything, only stoked the curiosity of Lord of the Rings and Dune enthusiasts alike, as evidenced by this thread from a few years ago on the r/tolkienfans subreddit. Was it the materialism and Machiavellianism implicit in Dune’s worldview? The preponderance of invented names and coinages that surely wouldn’t meet the etymological standard of an Oxford linguist?

Maybe it was the aristocratic isolation — a kind of anti-fellowship — of its protagonist Paul Atreides, who comes to possess the equivalent of Tolkien’s Ring of Power. “In Dune, Paul willingly takes the (metaphorical) ring and wields it,” writes Evan Amato at The Culturist. “He leads, transforms, and conquers. The universe bends to his vision. He suffers for it, yes, and questions it, but he never truly rejects the call to rule. Contrast this with the world of Middle-earth, where all Tolkien’s heroes do the opposite. When Frodo offers the Ring to Aragorn, he refuses. Even Samwise, humble as he is, feels the surge of the Ring’s power, and lets it go.” Assuming he managed to get through the first Dune novel, Tolkien could hardly have approved of the narrative’s moral arc. Whether his or Herbert’s vision puts up the more realistic allegory for humanity’s lot is another matter entirely.

Related Content:

Frank Herbert Explains the Origins of Dune (1969)

J. R. R. Tolkien Writes & Speaks in Elvish, a Language He Invented for The Lord of the Rings

Based in Seoul, ColinMarshall writes and broadcas**ts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities* and the book *The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Brian Eno’s Book & Music Recommendations

in * Books, Music * | December 30th, 2025

If you’re a regular listener, you know that Ezra Klein wraps up his podcast interviews with a familiar question: what three books would you recommend to the audience? When Klein interviewed Brian Eno in October, the producer had these three books to offer.

First up was Printing and the Mind of Man, a catalog from an exhibition held at the British Museum in 1963. “It was about the history of printing, but actually, the book is about the most important books in the Western canon and the impact that they had when they were released.” “It’s such a fascinating book because you really start to understand where the big, fundamental ideas that made Western culture came from.”

Next came A Pattern Language by the architect Christopher Alexander. “It’s really a book about habitat, about what makes spaces welcoming and fruitful, or hostile and barren.” Eno has returned to the book again and again over the years. “Over the course of my life, I’ve bought, I would say, 60 copies of that book because I always give it to anyone who is about to renovate a house or about to build a house. It’s a great read, and you would love it.”

His third recommendation was Naples ’44, a war diary kept by Norman Lewis, a British intelligence officer sent to Naples during World War II. “He kept a diary, and this is the most fabulous diary you’ll ever read. It’s just hilariously funny, deeply moving, and totally confusing—and you realize that Naples was, like, another planet.”

Understandably, Klein couldn’t let the interview end without also asking what albums influenced Eno most. In response, Eno offered The Rural Blues, a series of recordings of Black American music from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. It’s the same music that later inspired pop and rock musicians in England when Eno came of age. He also pointed to the Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album, calling it a “beautiful, beautiful record, beautifully controversial in many ways.” He then added: “In fact, probably without that record, I wouldn’t have been a pop musician.” Many other musicians have said the same.

And finally, despite being an atheist, Eno selected a gospel recording act known as The Consolers, best known for their 1955 track “Give Me My Flowers.” You can listen to more of their greatest hits here.

Alongside his musical and literary influences, Eno recently shared his own ideas in the book What Art Does: An Unfinished Theory.

**Related Content **

Brian Eno on the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music

A 6‑Hour Time-Stretched Version of Brian Eno’s Music For Airports: Meditate, Relax, Study

Brian Eno Creates a List of 20 Books That Could Rebuild Civilization

Jump Start Your Creative Process with Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” Deck of Cards (1975)

How Far Back in History Can You Start to Understand English?

in * English Language, History, Language * | December 29th, 2025

It’s easy to imagine the myriad difficulties with which you’d be faced if you were suddenly transported a millennium back in time. But if you’re a native (or even proficient) English speaker in an English-speaking part of the world, the language, at least, surely wouldn’t be a problem. Or so you’d think, until your first encounter with utterances like “þat troe is daed on gaerde” or “þa rokes forleten urne tun.” Both of those sentences appear in the new video above from Simon Roper, in which he delivers a monologue beginning in the English of the fifth century and ending in the English of the end of the last millennium.

An Englishman specializing in videos about linguistics and anthropology, Roper has pulled off this sort of feat before: we previously featured him here on Open Culture for his performance of a London accent as it evolved through 660 years.

But writing and delivering a monologue that works its way through a millennium and a half of change in the English language is obviously a thornier endeavor, not least because it i