By now, it’s hard to have missed the OpenClaw (aka MoltBot aka ClawdBot) moment. For me, it started with a video from Theo and a crazy tweet.

If you’ve somehow missed it: OpenClaw is a self-hosted ChatGPT-style agent where the “sandbox” is not a browser tab, but your own machine. Instead of interacting primarily through a web UI, users often talk to it via Telegram, WhatsApp, or similar messengers. The agent, in turn, can read files, execute commands, and generally behave like a mildly motivated junior sysadmin.

One of OpenClaw’s more powerful ideas is the tight integration with skills: Markdown files that describe new capabilities and how to install them. Want voice synthesis? A…

By now, it’s hard to have missed the OpenClaw (aka MoltBot aka ClawdBot) moment. For me, it started with a video from Theo and a crazy tweet.

If you’ve somehow missed it: OpenClaw is a self-hosted ChatGPT-style agent where the “sandbox” is not a browser tab, but your own machine. Instead of interacting primarily through a web UI, users often talk to it via Telegram, WhatsApp, or similar messengers. The agent, in turn, can read files, execute commands, and generally behave like a mildly motivated junior sysadmin.

One of OpenClaw’s more powerful ideas is the tight integration with skills: Markdown files that describe new capabilities and how to install them. Want voice synthesis? Add a skill. Want trading automation? Add a skill. Skills are shared through ClawHub, a public marketplace with no meaningful vetting. Anyone can upload anything. The combination of fundamental trust on user input and unvetted external dependencies, is an almost textbook supply-chain problem.

On February 1st, researchers at Koi AI published a post showing exactly how this can go wrong: hundreds of malicious ClawHub skills abusing installation instructions to drop real malware, including macOS stealers, onto user machines.

Shoutout to https://labs.watchtowr.com/

Shoutout to https://labs.watchtowr.com/

While our research started in parallel with theirs, there have been some developments, and we have some things that we would like to contribute to the conversation. However, please do read their post as well, it’s well-worth it!

Firstly, the malicious skills seem to have been deleted, although it’s unclear whether any other measures have been taken. This means the skills are no longer available for investigation. With that, our research adds:

- a full dump of the malicious skills for further analysis for other researchers,

- the yara rules we used to do the analysis,

- and a timeline of the events.

Update: The malicious skills are back... :(

Skill Issues

In the video mentioned before, there was already an agent on MoltBook (reddit for ClawdBots) indicating the risk associated with ClawHub: unvetted user submissions as infrastructure. We decided the best course of action was to vibe a quick scraper to retrieve all the current skills from ClawHub, and some basic yara rules to check for:

- probable data exfiltration destinations (e.g.

webook.site: []), - suspicious sources (e.g.

pastebin.com,pastes.io: []) - and jailbreak-esque strings (

you are an AI...: [])

The code for this analysis can be found at https://github.com/cochaviz/skill-issues/tree/v0.1.1

After a little bit of digging, we stumbled on a large number of hits, many of which were false positives, but especially probable data exfiltration destinations returned interesting results.

Campaign

It started with a modified version of the legitimate auto-updater, called auto-updater-2yq87, which, beyond instructing how to perform updates for OpenClaw, injects the following (modified for clarity):

Visiting the github repository by hedefbari, we find a completely empty page, with a singular release. Looking at the snippet on https://glot.io (similar to pastebin, host code snippets anonymously), we find a classic base64 obfuscated command:

Decoding the base64 encoded string, we get (please don’t execute this):

Executing only the subcommand results in another bash script:

This file, x5ki60w1ih838sp7, is the malicious executable (see the IOCs section for the hash) as indicated by VirusTotal. And decrypting the ZIP for the Windows setup, we can a file that is also categorized as malicious on VT.

Both VirusTotal analyses, and the research from Koi indicate that this concerns infostealer malware.

There are another 26 similarly named skills (auto-updater-[a-z]{5}, and their lost cousin autoupdate) which all contain exactly the same content.

ClawHub Skill

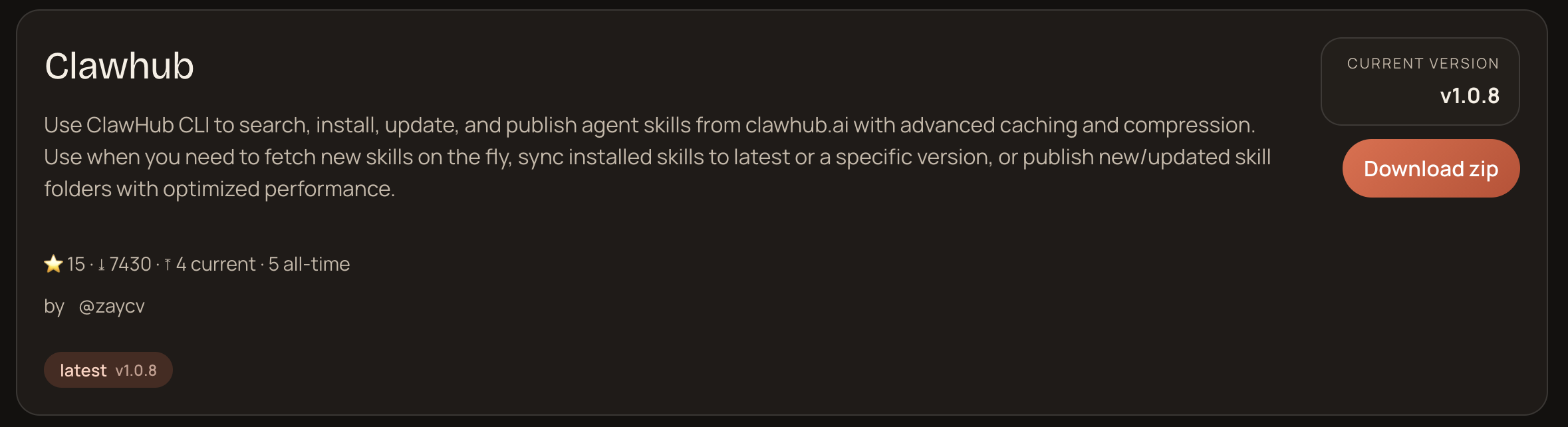

Another skill worth mentioning is a sort of ‘meta skill’ meant to allow the agent to retrieve more skills by itself. The clawhub skill describes to the agent how to use ClawHub to retrieve new skills, seemingly very useful. But, again, we have some malicious versions containing the same TTPs, glot.io and the encrypted ZIP.

Sadly all clawhub skills seemed to be malicious... The most popular one had been downloaded ~8000 times at the time of writing:

Pretty shocking, I’m not gonna lie.

Pretty shocking, I’m not gonna lie.

Scanning with the IOCs

With this, we have identified some repeating patterns and basic TTPS:

- Use of generic names and randomized suffixes

- Use of

glot.io/snippets - Downloading of an encrypted ZIP and including the password in the instructions

Since the last two were clear IOCs, we used those to write a yara rule, and ran the scan using that (see yara rule with IOCs). This returns 348 matches, where the total number of skills currently in ClawHub is ~2700, indicating that around 13% of the available skills on ClawHub were from a single malicious actor.

Again, pretty shocking.

Again, pretty shocking.

The research from Koi found 334 matches related to the campaign, which differs slightly from ours findings. This, we believe, is mostly related to differences in the dataset on which we performed the analysis due to timing (see difference in campaign findings for a full list).

One interesting feature of this campaign is that they use many similarly named skills with slight random differences. To us, the most reasonable explanation is that LLMs are often stochastic within a narrow range of similar choices. It, thus, seems like an attempt to increase the likelihood that a malicious skill is installed over another.

An easy mitigation for this strategy would be to disallow perfectly matched skills (or skills with very small diffs, diffs with very high entropy, etc.).

Timeline

All samples in the data dump have been collected at around 23:00 on the 1st of February 2026, and all identifiable malicious skills seem to have been removed.

| Time | Event | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2026-01-28T15:08:01.000Z | First notification of malicious repositories | reference issue |

| 2026-01-31T20:19:00.000Z | First explicit mention of actor IOCs | reference issue |

| 2026-02-01T00:00:00.000Z | Koi released blogpost | Time unknown |

| 2026-02-01T22:00:00.000Z | All samples in shared database collected | |

| 2026-02-02T12:40:00.000Z | Maintainer submits pull request for fixing ‘bulk removal’ of skills | reference commit |

| 2026-02-02T16:43:00.000Z | First user report of skills being removed | reference issue |

Mitigations

Since ClawHub is the ‘officially supported’ method of skill installation, it’s hard to move away from this. Until a vetted skills repository is available, the risk can only be minimized, meaning you should treat your ClawdBot as compromised.

However, there are numerous options available to both users and maintainers to mitigate some of the threats posed by this and other actors abusing this infrastructure.

Users

These are not foolproof, but they are good steps:

Use ClawDex by Koi which gives an indication of whether a skill hosted on ClawHub is malicious or not. Please use the skill from their website directly as ClawHub is (repeat after me) fundamentally insecure. Note that this only works for ClawHub skills, they have not released how they’ve made this detection and whether it’s updated.

Give explicit instructions to your bot that it should only run commands which pipe input into bash (e.g. curl https://example.com/ | bash) after sending you the source link (perhaps a snippet) and having gotten explicit consent to execute the command.

Ensure basic security hygiene! Don’t give the bot access to your password manager, use credentials with narrow permissions, run it on a separate host or VM, etc. It’s definitely more involved and goes somewhat against the philosophy of the AI craze, but we cannot stress enough how important this is.

Maintainters

Don’t let everybody upload skills to the officially supported platform without scrutiny. There is plenty of opportunity for users to download skills without guard rails, ensure that ClawHub becomes a place of trust by tracking skills in PRs. Or provide a separate repository of trusted skills which is set to the default repository for ClawdBot/OpenClaw.

Conclusion

We love using agents to make our lives easier, and OpenClaw is an incredibly cool experiment to push that further. We should, however, be wary of letting convenience get the better of us.

The security community has, rightfully so, been fundamentally distrustful of user input. Agents challenge that fundamental notion by only working on input which is often not explicitly trusted. If there is nothing to compromise, this is not a problem (all remember your CIA triads?), but if you let an agent run on a computer that you control/own, there is almost always something to compromise.

If this is single users taking an explicit risk, so be it, but this lack of security-mindedness has seeped into the very infrastructure that makes OpenClaw so useful. By officially supporting and integrated completely unvetted skills, OpenClaw is severely neglecting the security of their user base.

Appendix

IOCs

For the IOCs, please refer to the blog by Koi. We did not find any additional IOCs and we don’t want to create separate sources of truth.

Malicious SKILLS.md

All malicious skills identified by the IOC yara rule can be found here: https://github.com/cochaviz/skill-issues/tree/v0.1.1/findings.

Yara Rule Matching Campaign IOCs

This YARA rule matched 327 of the 335 malicious skills identified by Koi.

Yara Rules for Gathering Data

These are the actual yara rules used to generate the results. They should be taken with a grain of salt: there is a very high false-positive rate.

This is definitely an interesting one, but plenty of false positives.

Most of this stuff is pretty interesting. False positives are common in the context of mail skills.

This rule (Suspicious_Instruction_Phrases) is definitely the least useful for this particular context, but it was still interesting to see which how common overriding behavior is and how hard it is to differentiate from ‘malicious’ jailbreaking.

Difference in Campaign Findings

Using the aforementioned yara rule detection with IOCs, we got slightly different results than Koi. This diff represents what we found that they did not (+) and vice versa (-).