- 24 Dec, 2025 *

When you’re selling stuff, every click away from your website is a potential lost sale. Customers kept asking us to allow people to buy tickets without leaving their branded site. They loved the service, but wanted to retain brand presence and coherence.

The ask seemed simple enough. Drop a widget on any webpage, show some events, let people check out. But as we dug into it, the technical challenges started stacking up. How do you maintain cart state across page refreshes? How do you track marketing attribution when the purchase happens on someone else’s domain? And how do you process payments securely in what is essentially a third party context?

This is the quick post of how we tried a bunch of approaches, hit walls, and eventually landed on Phoenix Channels as …

- 24 Dec, 2025 *

When you’re selling stuff, every click away from your website is a potential lost sale. Customers kept asking us to allow people to buy tickets without leaving their branded site. They loved the service, but wanted to retain brand presence and coherence.

The ask seemed simple enough. Drop a widget on any webpage, show some events, let people check out. But as we dug into it, the technical challenges started stacking up. How do you maintain cart state across page refreshes? How do you track marketing attribution when the purchase happens on someone else’s domain? And how do you process payments securely in what is essentially a third party context?

This is the quick post of how we tried a bunch of approaches, hit walls, and eventually landed on Phoenix Channels as our solution.

The Business Problem

Our platform handles ticketing for comedy shows and events. Most of our customers have their own websites where they promote their shows, but when someone wants to buy a ticket, they get redirected to our checkout flow. That redirect isn’t an issue if you’re coming from Google or some social media platform, but it is a point of friction if you’re coming from someone else’s website and already viewing event information there.

The numbers were fairly clear: cart abandonment spiked whenever users had to leave the original site. People would click "Buy Tickets", land on our domain, get distracted, and never complete the purchase. Our customers wanted a way to keep buyers on their own turf through the entire flow.

So we set out to build an embeddable widget that could handle the complete purchase experience. Browse events, add to cart, enter customer info, pay with Stripe, get confirmation. All without leaving the host page.

What We Needed to Solve

Beyond the basic checkout flow, we had a bunch of technical requirements that made this tricky.

First, we needed to track marketing parameters. When someone lands on a page with utm_campaign or fbclid in the URL, those values need to follow the user all the way through checkout so we can attribute the sale correctly. Same deal with referral codes and other tracking identifiers.

Second, we needed location detection. Different regions have different currencies and tax rules. We needed to figure out where the user was coming from and apply the right pricing.

Third, cart persistence. If someone adds tickets to their cart and then refreshes the page, that cart better still be there. And ideally, if they come back the next day, same thing.

Fourth, conversion tracking. When an order completes, we need to fire Meta Pixel events, Google Tag conversions, Reddit Pixel tracking. All the usual suspects for marketing attribution.

And finally, all of this had to work on any website, regardless of what tech stack they’re running. WordPress, Squarespace, custom Rails apps, static HTML. The widget needed to just work.

The Approaches We Tried

Web Components with REST

Our first instinct was the obvious one. Build a Web Component that makes REST calls to our API for everything. Add to cart? POST request. Update quantity? PUT request. Checkout? More requests.

We actually had an older implementation using this pattern from a few years back, built with Stencil. We got a prototype working pretty quickly. The problem was state management. Keeping the web component UI state in sync required us to retrieve data every time something changed and the component became a giant HTTP client with tons of boilerplate and error handling code. This isn’t necessarily bad, but a core tenet of Elixir development is to reduce boilerplate and opt for messaging over RPC, so we quickly ditched this approach.

The bigger issue was that we were essentially rebuilding our entire checkout flow in JavaScript. All the price formatting logic, the discount calculations, the conditional display rules based on product configuration. We had all of this working beautifully in Elixir already. Duplicating it on the client felt wrong. The client side code didn’t get gnarly, but there was considerable duplication of what the web component was rendering, and what our website was rendering.

iframes

Next we tried the iframe approach. Just embed our existing checkout in an iframe on the host page. This way we could reuse all our LiveView code with zero modifications.

The cross origin communication was the first problem. Getting the parent page and the iframe to talk to each other meant a bunch of postMessage calls with careful origin checking. But the real killer was third party cookies.

Modern browsers are cracking down on third party cookies hard. Safari was already blocking them by default, Chrome is phasing them out, Firefox has restrictions. Our session management relied on cookies, and suddenly half our users couldn’t stay logged in through the checkout flow. The iframe approach was dead on arrival even though the PoC worked. Chasing the JavaScript stack and tracking all the latest tweaks browsers and libraries make isn’t a business worth getting into.

LiveView Inside Web Components

This one seemed promising. Phoenix LiveView gives you that real time reactivity we wanted. What if we could mount a LiveView inside a Web Component’s Shadow DOM?

We spent a good chunk of time trying to make this work. The problem is that LiveView’s DOM patching fundamentally conflicts with Shadow DOM encapsulation. LiveView needs to own the DOM tree it’s managing, and Shadow DOM creates a boundary that the patching algorithm can’t cross properly. Event delegation breaks. The morphdom updates don’t penetrate the shadow boundary correctly.

We looked at the Phoenix source code, read through the forums and Discord. The consensus was clear: this isn’t a supported pattern and probably never will be even though libraries like live_portal are trying hard to solve it.

Other Libraries

We evaluated a bunch of other options. Hologram looked interesting but connecting the web component’s socket to what Hologram seemed brittle and intrusive, especially as Hologram is relatively early stage and APIs are likely to change. LiveVue and LiveSvelte are designed for using those frameworks inside LiveView, not the other way around.

None of them gave us what we needed.

Why Phoenix Channels Worked

The breakthrough came when we stopped trying to embed LiveView and started thinking about what we actually needed from the server.

We didn’t need the full LiveView abstraction. We needed real time communication with state management. We needed the server to be able to push updates when things changed. And we already had this infrastructure running: Phoenix Channels.

Channels give you a persistent WebSocket connection with built in topic subscription, message passing, and presence tracking. We use them extensively for other features in the platform. Why not for the widget?

The key insight was realizing we could send rendered HTML over the channel instead of JSON. This sounds backwards at first. Aren’t you supposed to send data and let the client render it? But hear me out.

By rendering HTML on the server, we get to reuse all our existing Elixir code. Price formatting that handles multiple currencies and locales? Already written. Display logic that varies based on brand settings? Just a function call away. Conditional rendering for sold out events versus available ones? Same templates we use everywhere else.

If we sent JSON, we’d have to duplicate all of this in JavaScript. And then keep the two implementations in sync. This might follow some esoteric separation of concern goals, but it feels wonky and unnecessary. Also, we’re essentially the same app.

The other thing about WebSockets is they’re fast. Once that connection is established, you’re not paying the TCP handshake cost on every interaction. Headers get stripped down to almost nothing. For something like a cart that might see dozens of updates in a session, that overhead reduction adds up.

And browser support? WebSockets have been solid across all major browsers since 2011. This isn’t experimental technology.

The Architecture

Here’s how the pieces fit together.

On the client side, we have a Web Component called product-list-widget. You drop it on any page with a script tag and a custom element, pass it a widget ID as an attribute, and it handles the rest.

We debated between Lit and Stencil for building the Web Component. We had used Stencil in our original REST based implementation years ago, but this time we went with Lit. Stencil is more oriented toward building design systems and component libraries, with its own compiler and build toolchain. For our use case of a single focused widget, Lit’s lighter weight approach made more sense. You just extend a base class and you’re done.

When the component mounts, it establishes a WebSocket connection to our Phoenix application and joins a channel specific to that widget. The channel handler on the server looks up the widget configuration, fetches the relevant products, renders the initial HTML, and sends it back.

From there, every user interaction goes through the channel. Click add to cart? The component sends a message, the server updates the cart, renders the new state, and replies with HTML. During checkout it’s the same pattern. The server handles the business logic and responds with the next view to display.

Host Website (any domain)

└── product-list-widget (Web Component)

└── Phoenix Channel Connection

└── ProductListChannel

└── CheckoutService (shared with main site)

└── All our existing Elixir code

The Web Component provides encapsulation so our styles don’t leak into the host page and vice versa. The Shadow DOM keeps everything contained.

Handling Parameters

One of the first problems we hit was tracking parameters. When someone lands on a page with marketing UTMs in the URL, we need to capture those and associate them with any purchase that happens.

The solution is straightforward. When the widget initializes, it reads the current URL and extracts any parameters we care about. UTM campaign, source, medium. Facebook click IDs. Referral codes from our affiliate program. Venue access codes for special pricing.

These get sent along when joining the channel. On the server side, we stash them in the socket assigns and later write them into the cart context when the cart gets created.

const trackingParams = {

utm_campaign: url.searchParams.get('utm_campaign'),

utm_source: url.searchParams.get('utm_source'),

fbclid: url.searchParams.get('fbclid'),

customer_referral_code: url.searchParams.get('customer_referral_code'),

ref: url.searchParams.get('ref')

};

channel.join("product_list:1", { tracking_params: trackingParams });

When the order eventually completes, all these parameters are sitting in the cart context, ready for our analytics pipeline to process.

Location Detection

Currency and tax rules depend on where the buyer is located. We handle this by grabbing the IP address from the socket connection and running it through a geolocation service.

The channel join handler pulls the IP from the socket, looks up the location, and uses that to determine the default currency and region. If we detect someone in Canada, they see Canadian dollars. Someone in the US sees USD.

This happens transparently on the first connection. The user doesn’t have to select their country from a dropdown or anything like that. We just figure it out and show them relevant pricing.

Cart Persistence

LocalStorage handles cart persistence on the client side. When we create a cart on the server, we get back a cart ID. The widget stores that ID in LocalStorage keyed by the widget ID.

Next time the page loads, the widget checks for an existing cart ID and sends it along when joining the channel. The server validates that the cart exists and is still usable, then restores the previous state. If the cart has expired or been completed, we just start fresh.

private getStoredCartId(): string | null {

return localStorage.getItem(`widget_cart_${this.widgetId}`);

}

private storeCartId(cartId: string): void {

localStorage.setItem(`widget_cart_${this.widgetId}`, cartId);

}

This works around the third party cookie problem entirely. LocalStorage is partitioned by origin, but the widget JavaScript runs in the context of the host page, so it has access to that page’s storage.

DOM Diffing with Idiomorph

Here’s a detail that makes a huge difference in user experience. When the server sends back new HTML, we don’t just blast it into the DOM with innerHTML. That would reset focus on input fields, lose scroll position, and generally feel janky.

Instead we use Idiomorph, a library that does intelligent DOM diffing and morphing. You give it the current DOM and the new HTML you want, and it figures out the minimal set of changes needed to transform one into the other. Elements that haven’t changed stay put. Focus stays on the input you were typing in. Scroll position is preserved.

import { Idiomorph } from 'idiomorph';

private updateContent(html: string) {

Idiomorph.morph(this.contentContainer, html, {

morphStyle: 'innerHTML'

});

}

This gives us LiveView style reactivity without actually using LiveView. When you update your cart quantity, the rest of the page stays exactly where it was. You don’t lose your place or have to refocus on the field. It feels smooth.

Payment Integration

Stripe Elements handles the payment UI. After the customer fills in their info and clicks continue, we create a PaymentIntent on the server and send back the client secret along with instructions to show the payment form.

The widget mounts Stripe Elements into a container within the Shadow DOM. User enters their card, we confirm the payment with Stripe, and on success we send a message back through the channel to complete the order.

Free orders skip the Stripe step entirely. If the cart total is zero (maybe they used a 100% off promo code), we just submit the order directly without involving payment processing.

Conversion Tracking

Getting conversion pixels to fire correctly took some thought. On our main site, we use LiveView’s push_event/3 to send conversion data to a JavaScript hook that fires the various tracking pixels. But in the widget context, we don’t have LiveView hooks.

The solution is to include the conversion event data in the order success response. When an order completes, the server looks up what analytics elements are configured for that account, builds out the event payloads for each one, and includes them in the response.

{:ok, conversion_events} = CheckoutService.get_order_conversion_data(order_id)

{:reply, {:ok, %{

html: render_success_view(order_data),

view: "success",

conversion_events: conversion_events

}}, socket}

On the client side, we iterate through those events and fire them using the appropriate global functions. fbq for Meta, gtag for Google, rdt for Reddit.

if (response.conversion_events?.length) {

setTimeout(() => {

this.fireConversionEvents(response.conversion_events);

}, 2000);

}

The two second delay matches what we do on the main site. It gives the page time to stabilize before we start making network requests to third party tracking services.

One caveat here: the host page needs to have these tracking libraries loaded. If they haven’t included the Facebook Pixel script, our fbq calls just silently fail. We log a warning to the console but don’t crash.

Reducing Duplication

One of the things we were most worried about was maintaining two parallel implementations. The main site checkout and the widget checkout doing the same things in slightly different ways.

We solved this by extracting shared logic into a CheckoutService module. Cart validation, customer adding, Stripe setup, order completion. All the core checkout operations live in one place and get called from both the LiveView code and the channel handlers.

defmodule AmplifyWeb.CheckoutService do

def complete_cart_with_validation(cart_id)

def setup_stripe_payment(cart_id, currency_code)

def add_customer_to_cart(cart_id, customer_params, opts)

def validate_customer_params(params)

def get_order_conversion_data(order_id)

end

Before this refactor, we had the same cart completion logic written out in three different places. Each one had slight variations that had accumulated over time. Consolidating them into a single service eliminated about a hundred lines of duplicated code and gave us one canonical implementation to maintain.

The conversion event building is a good example. Both the CartComplete LiveView and the widget channel need to fire the same tracking pixels with the same data. Now they both call the same get_order_conversion_data/1 function and get the same events back.

What we didn’t try to share is the template rendering. The widget uses string interpolation templates since it’s returning raw HTML over the channel. The main site uses HEEx templates with all the LiveView compile time goodness. These are fundamentally different rendering contexts, and trying to abstract over them would have been more trouble than it’s worth. DRY isn’t always good, sometimes some duplication is OK.

Monorepo Structure

We keep the Lit widget code in the same repository as the Phoenix application. The widget lives in assets/widget/ with its own package.json, TypeScript config, and build scripts. This wasn’t an obvious choice at first since we could have created a separate npm package and published it independently.

The monorepo approach won out for a few reasons. First, the widget and the server are tightly coupled. When we change how the channel sends data, we often need to update how the widget handles it. Having both in the same repo means we can make those changes atomically in a single commit. No version coordination, no wondering if the deployed widget matches the deployed server.

Second, shared types. We generate TypeScript interfaces from our Elixir structs for the channel message formats. Keeping everything together means the types stay in sync automatically. When we add a field to a response, the TypeScript compiler immediately tells us everywhere that needs updating.

Third, simpler CI. One repo means one pipeline. We run the Elixir tests, build the widget, and deploy everything together. If the widget build fails, the whole deploy fails. No chance of shipping a broken widget because someone forgot to bump a version number.

The build process is straightforward. We have a mix task that shells out to npm to build the widget, then copies the output to priv/static/widget/. The widget JS and CSS get served as static assets. When someone includes our script tag, they’re pulling from the same CDN that serves the rest of our static files.

amplify/

├── lib/ # Elixir code

│ └── amplify_web/

│ └── channels/

│ └── product_list_channel.ex

├── assets/

│ ├── js/ # Main app JavaScript

│ └── widget/ # Widget package

│ ├── src/

│ │ └── product-list.ts

│ ├── package.json

│ └── tsconfig.json

└── priv/static/widget/ # Built widget output

This also helps with our customer UX as they just have to paste a script tag into their Squarespace site. Hosting the widget ourselves and keeping it in the monorepo gives us full control over the experience.

What We Learned

Start with the primitives you already have. We wasted some timeim trying to shoehorn LiveView into a context it wasn’t designed for. Phoenix Channels were sitting right there the whole time, battle tested and ready to go. Sometimes the answer isn’t a new library or a clever workaround. It’s the boring infrastructure you’ve been using for years.

Server rendered HTML over WebSockets is underrated. The conventional wisdom says send JSON and render on the client. But that only makes sense if you don’t already have rendering logic on the server. We had years of Elixir code handling edge cases in price formatting, discount calculations, and conditional display logic. Sending HTML meant we could reuse all of it. The widget got our production tested rendering for free.

DOM diffing libraries are table stakes for any dynamic UI. We almost shipped with raw innerHTML updates. The first time we saw a user lose their place in a form because the whole container re-rendered, we knew we needed Idiomorph. The integration took maybe two hours. The UX improvement was immediate and obvious. If you’re updating DOM content dynamically, use a morphing library. It’s not optional.

LocalStorage beats cookies for cross origin state. The iframe approach died because of third party cookie restrictions. LocalStorage doesn’t have that problem since the widget runs in the host page’s context. The tradeoff is that carts are now per device rather than per user session, but for our use case that’s actually fine. Most ticket purchases happen in a single session anyway.

Monorepo simplifies everything when client and server are tightly coupled. We briefly considered publishing the widget as a separate npm package. The coordination overhead would have been brutal. Every channel message format change would require syncing versions across repos. Keeping everything together means atomic commits and one deployment pipeline. The simplicity is worth the slightly larger repo.

Wrapping Up

Phoenix Channels gave us the foundation we needed to build an embeddable widget that actually works. The persistent WebSocket connection handles real time updates elegantly. Sending rendered HTML lets us reuse our existing Elixir codebase. Idiomorph keeps the DOM updates feeling smooth.

If you’re building something similar with Elixir and Phoenix, consider whether channels might be a better fit than trying to embed LiveView directly. The pattern of Web Component plus Channel plus server rendered HTML is surprisingly powerful and sidesteps a lot of the complexity we ran into with other approaches.

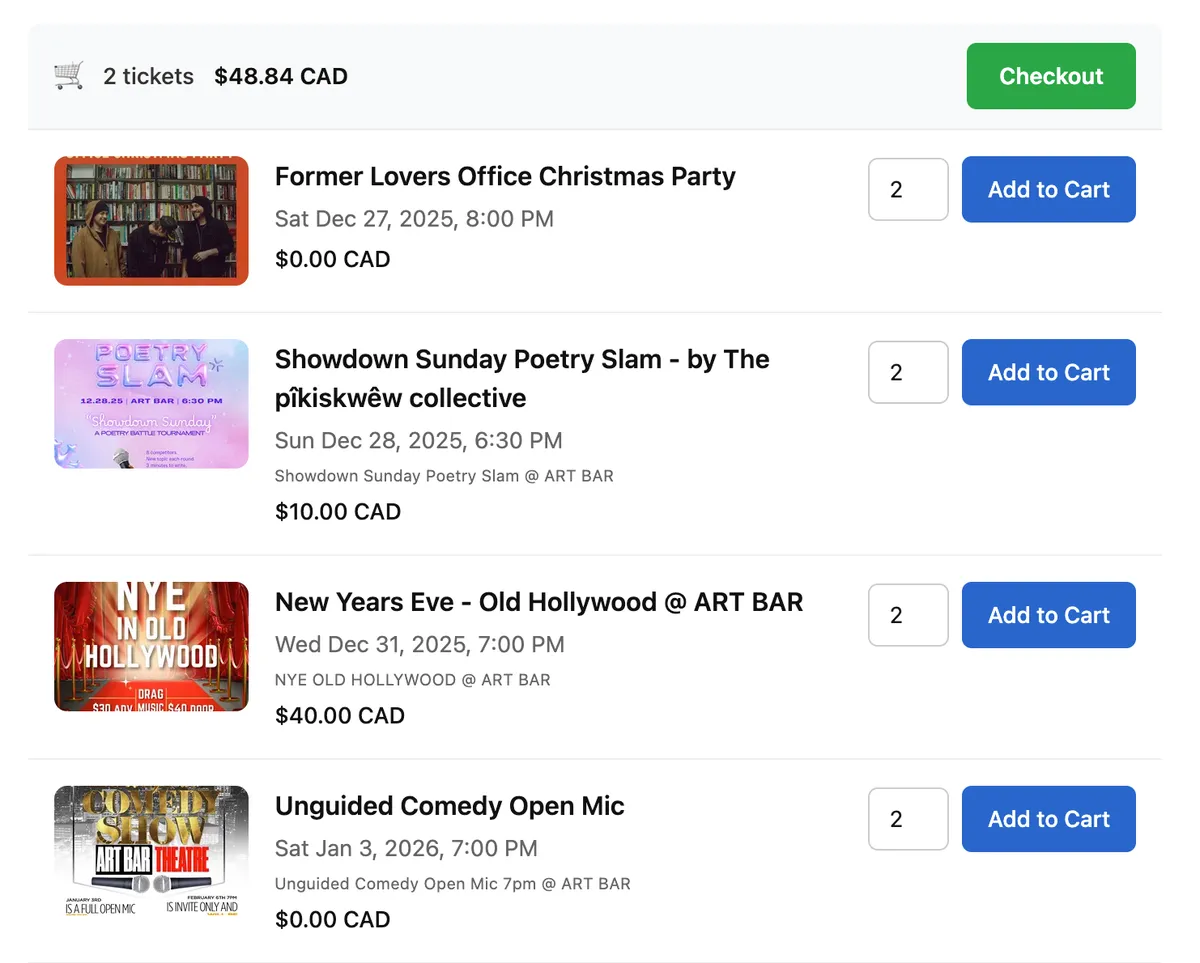

The widget is now running in production on customer sites across different platforms and tech stacks. Drop in a script tag, add the custom element, and you’ve got a full checkout flow without sending users anywhere. Here’s what the final widget looks like: