Background: European Papermaking Techniques 1300-1800

Timothy Barrett

On this page:

- Introduction

- Raw Materials

- Retting

- Intermediate Steps

- Stamper Beating and Washing during Beating

- Sheet Forming

- Drying

- Sizing

- Finishing

- Aesthetics

- Additional Information on Hand Papermaking

- Citations

Introduction

The following essay describes the materials and techniques used to make paper by hand in Europe between 1300 and 1800 CE. Some have questioned ending at 1800 when the real trouble with paper stability was just beginning. The 1300 through 1800 period, however, represents the rise and the slow but certain decline …

Background: European Papermaking Techniques 1300-1800

Timothy Barrett

On this page:

- Introduction

- Raw Materials

- Retting

- Intermediate Steps

- Stamper Beating and Washing during Beating

- Sheet Forming

- Drying

- Sizing

- Finishing

- Aesthetics

- Additional Information on Hand Papermaking

- Citations

Introduction

The following essay describes the materials and techniques used to make paper by hand in Europe between 1300 and 1800 CE. Some have questioned ending at 1800 when the real trouble with paper stability was just beginning. The 1300 through 1800 period, however, represents the rise and the slow but certain decline of hand papermaking as a major industry. In the late 1700s traditional methods were still in use in many mills. After 1800, however, the craft was rapidly changed by various “improvements,” including the papermaking machine, the universal acceptance of the Hollander beater, chlorine bleach, rosin and alum internal size, and the introduction of impure wood-pulp fibers as a substitute for rags.

What follows is an attempt to give a detailed picture of the tools and techniques used by early European papermakers to make high-quality book and writing papers. It is based heavily on an essay I first published in 1989 and it is presented again here with permission of the original publisher.1 The text draws as well on the earlier and the current research, my own experience as a papermaker, and the sources cited in the endnotes. By and large, the latter sources are well known to paper historians. In a number of instances scholars working in related fields have offered especially interesting references or made other important contributions. John Bidwell, Howard Clark, Richard L. Hills, and Leonard Rosenband gave especially generous support on the occasion of the original 1989 publication and their help remains much appreciated in the context of this website.

The literature of papermaking is sparse until the mid-eighteenth century, when the French writers Jérôme Lalande, Louis-Jacques Goussier, and Nicolas Desmarest began documenting the craft in their country.2 The absence of details from earlier periods is no doubt a result of trade secrecy, the habit of passing skills directly to family members or in-laws rather than to outsiders, and the lack of ability, time, or need to document the craft in writing.

As a result, what follows is in part generalization and in part hypothesis. Generalizations are dangerous. Attempting to describe the methods used to make paper in Europe between 1300 and 1800 in a short essay such as this is like trying to describe the methods used to make cheese throughout the continent during the same period. The raw materials, local conditions, routines, and traditions were almost certainly very diverse. But a generalization, once understood as such, is probably the best way we have of looking back over the past, especially if the subject is new to us. To hypothesize is dangerous as well, but if the hypothesis is based on knowledge and expertise, it can add considerably to our general sense of what actually transpired.

In summary, what follows is a guess, based on limited research, about what may have been the routine in a mill producing high-quality papers somewhere in Europe between 1300 and 1800. If this text broadens the reader’s view of the craft only a bit, raises new questions, and inspires new research, it will be ample reward for the effort.

Readers interested in the briefest introduction to how sheets of paper were made by hand, pressed, and dried may wish to jump to the “Sheet Forming” section below. Alternatively, or in addition, they can view excellent short YouTube videos showing papermaking by hand.3 Another related site gives an interactive view of the spread of papermaking and printing across Europe during the fifteenth century.4

Timothy Barrett August, 2011 Iowa City, Iowa****

Raw Materials

Water

For anyone who has tried to make paper free of specks and other debris, it is not hard to imagine the concern about water quality in any mill where high-quality white paper was in production. For papermakers of any era, stray bits of foreign matter seem to enter the pulp no matter how much care is taken to keep them out. Diligence and attention are the only ways to win the battle. Clear, fresh water is, and was, of the essence. Lalande describes eighteenth-century water-treatment systems consisting of settling tanks and sand filters used to clear particulates from incoming process water.5 In another mill, says Lalande,

the water arrives in the stamping-troughs, only after having passed through a wicker straining basket from the canal, a water-outlet designed to precipitate the dirt, a strainer in the large settling tank, a water-outlet and a very fine grid in the small settling tank, often several piles of rags, and finally through the strainer of the small feed tank: all of these precautions have their use; one can never be too careful when it is a question of the purity of the water used on the rags and in the making of the paper.6

Alfred Shorter, in his work on papermaking in England, cites “plentiful, pure and clear or ‘fair’ water” as one of the essential ingredients in producing white paper of good quality.7 Separating process water from water used for power was an alternative, and often a routine necessity. A nearby spring might offer top-quality water for actual papermaking, while the immediate river would be used only for power. (This was the normal working arrangement at J. Barcham Green in England for some time, until use of the water wheel was discontinued).8

While it is unlikely that papermakers were knowledgeable about the contribution of calcium and magnesium carbonate to paper permanence, they would easily have noted the ill effects of water high in iron content by the reddish or brownish cast it gave their paper. The historical papers with lighter and less red colors analyzed during this research contained higher calcium and lower iron concentrations. Calcium compounds such as lime are known to have been use in early papermaking. Józef Drabowski and John Simmons cite F. M. Grapaldo’s 1492 description of the addition of lime to the stamper pits.9 This was likely done to help swell the cellulose and expedite fiber shortening and fibrillation during stamping. Ground chalk might have been added in small amounts as a whitener to counteract the yellowing effects of retting or iron in the water. Limed skins and other animal parts used to make gelatin size may have been another source. Finally, at least a portion of the calcium compounds entered the paper via the water supply. Calcium and magnesium carbonate can appear as sources of hardness in ground and surface water. During papermaking, cellulose fiber very rapidly accumulates metals dissolved in water, be they favorable or unfavorable to the permanence of the paper.

While Lalande and other writers seem to indicate a preference for soft water free of iron and other hardness promoting components because of its apparent ability to degrease the rags more readily and dissolve sizing, it is likely that much of the available water had a degree of natural hardness. The analyses I reported on in 1989 showed considerably more residual metals in historical specimens than in modern handmade sheets produced in a laboratory with soft (deionized) water.10

In summary, if the early papermaker took care to obtain a supply of fresh water free of iron and debris, he was, more often than not, on the right track to making quality paper. The makers of many of the better-quality sheets studied during this research had to have been very aware of the quality of the process water entering their mills.

Fiber

To appreciate the nature of the rags used as raw material in early European papermaking, we need to consider textile manufacture of the period. Raw flax and hemp fiber are both naturally dark in color as a result of the encrusting plant material that remains attached to the fiber after its separation from the inner stalk or straw of the plant. Since strong chemicals and bleaches were not available at the time, it required time, considerable handwork, and patience to produce a very light-colored fabric from material woven of these fibers. A revealing chart by M. Th. Mareau (as cited by A. Proteaux) gives an indication of the work and loss occurring during the gradual transition of raw flax plants into paper.11

Figure 1. Loss in weight of raw flax during the transition into paper

| Condition of the Material | Kilograms |

|---|---|

| Raw picked flax | 100.00 |

| Dry flax | 25.00 |

| Rippled flax | 17.50 |

| Retted flax | 4.40 |

| Combed flax | 4.18 |

| Spun thread | 3.55 |

| Linen cloth | 2.84 |

| White linen | 2.41 |

| Papermaking | 1.69 |

Ignoring the steps involved in processing raw flax into linen cloth, the following account by Dr. Francis Howe, from John Horner’s Linen Trade of Europe (1755; abbreviated by me), gives some idea of the work required to produce white linen fabric using “the old Dutch method.”12

After the cloth has been sorted in to parcels of an equal fineness, as near as can be judged, they are . . . steeped in water, or equal parts water and lye . . . from thirty-six to forty-eight hours. . . . The cloth is then taken out, well rinsed . . . and washed. . . . After this it is spread on the field to dry. When thoroughly dried it is ready for bucking or the application of salts. [The liquor used in bucking was made from a mixture of ashes in water.] This liquor is allowed to boil for a quarter of an hour, stirring the ashes from the bottom very often, after which the fire is taken away. The liquor must stand till it has settled, which takes at least six hours and then it is fit for use. . . . After the linens are taken up from the field, dry, they are [immersed in the lye] for three or four hours. . . . The cloth is then carried out, generally early in the morning, spread on the grass, pinned, corded down, exposed to the sun and air and watered for the first six hours, so often that it never is allowed to dry. . . . The next day in the morning and forenoon, it is watered twice or thrice if the day is very dry, after which it is taken up dry again . . . fit for bucking. . . . This alternate course of bucking and watering is performed for the most part from ten to sixteen times, or more, before the linen is fit for souring. . . .

Souring, or the application of acids . . . is performed in the following manner. Into a large vat or vessel is poured such a quantity of buttermilk or sour milk as will sufficiently wet the first row of cloth. . . . Sours made with bran or rye meal and water are often used instead of milk. . . . Over the first row of cloth a quantity of milk and water is thrown, to be imbibed by the second, and so it is continued until the linen to be soured is sufficiently wet and the liquor rises over the whole . . . [and] just before this fermentation, which lasts five or six days, is finished . . . the cloth should be taken out, rinsed, mill-washed, and delivered to the women to be washed with soap and water. [Then it was carried outdoors to be bucked yet again.] From the former operation these lyes are gradually made stronger till the cloth seems of a uniform white, nor any darkness or brown color appears in its ground. . . . From the bucking it goes to the watering as formerly . . . then it returns to the souring, milling, washing, bucking and watering again. These operations succeed one another alternately till the cloth is whitened, at which time it is blued, starched, and dried.

Horner adds:

This process, including the field bleaching, required from six to eight months to complete. At Haarlem this industry continued large and lucrative until the end of the eighteenth-century, when the modern system of bleaching by the agency of chlorine practically stifled it.

Doubtless, many rags that found their way into paper did not receive this sort of attention during their original manufacture. Rough or off-white rags and tough and strong waste material such as old ropes, sails, and canvas certainly ended up in the sorting rooms of paper mills, but such materials were set aside for making rougher-quality papers, wrapping paper, or board. Rags of the finest quality used for making better-quality paper, however, very likely started off being bleached using the “old Dutch method” described above. Thereafter such items were repeatedly washed, and used again and again until they became too weak to be serviceable and were finally collected as rags and sold to the paper mill.

The excellent formation quality apparent in some of the better historical specimens tested during this project, in combination with the rather short fiber lengths encountered during the 1989 research13 suggest that great care was taken in sorting the raw material. Less attention was necessary if a poorer-quality or thicker paper was being made. Caustic chemicals and high-pressure cooking equipment were not available to weaken a strong raw material. The stampers, though shod with iron teeth and quite capable of cutting, were slow, and prolonged time in the stamper pits cost money. Therefore, a fine-quality white paper with good look-through was most readily and economically made by first selecting well-worn white rags of a similar strength.

This step in the process, like all those that followed, required skill and experience. Women and girls worked in the rag-sorting rooms of paper mills, and the younger ones learned from their mothers or other relatives. Important sensitivities were passed from one to another while working together day after day, year after year.

Figure 2. Sorting rags into grades of varying quality and strength.

Note: This and the historical plates that follow are all from the Diderot Encyclopédie published in Paris between 1751 and 1765.14 No images have come to light that show the same steps in fourteenth- or fifteenth-century European papermaking, and therefore these rather idealized depictions of the steps in eighteenth-century papermaking workplaces will have to suffice.

Lalande indicates that the women in mills in the Auvergne sorted rags into three grades: fine, medium, and coarse. However, he adds,

"Those [mills that] wish to take even more care over the sorting have up to six compartments for six grades of rag: superfine, fine, fine seams, medium, medium seams and coarse, without taking into account the extremely coarse matter which is discarded."15

Poorly sorted rags, stronger than the rest in a graded lot, could cause those in charge of retting and stamping tremendous headaches. With regard to retting, Lalande warns that

rags with varying degrees of strength and wear react in different ways to the retting process. Some are already spoilt when others have not yet shown the effects of the first fermentation; it is necessary, therefore, to put rags of similar qualities, chosen with great care, to work together if one does not wish to run the risk of ruining the whole by the inclusion of cloth which differs radically from the remainder.16

At stamping, remaining bits and pieces of the stronger material would force the crews to prolong the stamping, to clear up the pulp, risking its ruin. Unlike the Hollander beater in which the roll-to-bedplate opening could be adjusted to minimize damage to already separated and shortened fiber, the stampers continued to work on every fiber caught under their blow. The secret of success was therefore to start with a carefully culled batch of rags of similar weight, color, and tenderness. The entire lot of fiber had to finish in the stampers at the same time. Without access to rags in a range of qualities, and skilled workers in the sorting rooms, a mill would have had no choice but to make only rougher-quality papers. Henk Voorn describes an eighteenth-century Swedish attempt to hire skilled workers from Dutch paper mills. One of the first workers to be located, Voorn tells us, was “a highly skilled sorter,” since the high quality of Dutch paper was considered to be a result, at least in part, of careful sorting of the rags.17

Regarding the use of hemp, flax, and cotton fiber in papers from this period, microscopic analyses by Thomas Collings and Derek Milner of paper specimens made in Europe between 1400 and 1800 generally showed mixtures of hemp and flax fiber with higher concentrations of hemp (e.g., 75%) during the earlier dates.18 While cotton, or cotton-containing fabrics, were available in Europe during this period, their use was not common enough to generate substantial cotton-rag material for papermaking until the nineteenth century. Cotton fiber in significant quantity is therefore rare in papers before 1800, according to these researchers.19

The question naturally arises as to the use of new fiber, in the form of waste generated during processing of plant to fiber to thread or new textile cuttings. Raw unspun fiber, thread, and unbleached cloth waste were certainly available, but their strength in combination with their often dark color would have relegated them to use only in thicker, poorer, rougher-quality papers. Whitened new material in the form of cuttings from garment making or other sources must also have been at hand, but its strength was still a disadvantage. Fermentation and stamping techniques could have been employed to reduce any type of fiber to the proper length for papermaking, but only with great expenditure of time, space, and labor. “New material,” writes Lalande, “is not altogether suitable; it takes too long to fine down.”20

While apparently new, long fibers do seem prevalent in some thick papers used as cover stock in Italian limp-paper binding, such fibers were rare in the 130 historical book-paper specimens selected for the 1989 research.21 There were only four examples (specimens P160, P153, P79, and P43). All were thin, gray, knotty, and made of pulp that seemed to consist, at least partly, of a long fiber, perhaps new flax or hemp waste, combined with recycled printed paper. One other quite long-fibered paper (G17) was noted, dating from around 1400 based on the watermark. It may have been made from raw fiber, but is more likely to have been made from select, carefully prepared rag. Generally, a wide variety of old, well-worn and tender materials formed the bulk of the rag stock in mills where high-quality book papers were being made.

Figure 3. Cutting rags into smaller pieces and removing buttons, pins, and other foreign matter.

It is worth exploring the role washing soaps, diet, and personal hygiene may have played in affecting the nature of these old hempen and linen rags before they came to the paper mills. For instance, Fernand Braudel tells us that Europeans appear to have bathed less and less from the fifteenth and into the seventeenth century, and that public baths became less prevalent after the sixteenth century.22 He also tells us that the rather high consumption of meat in Europe declined after 1550, suggesting a greater likelihood of residual animal fats in rags before that date.23 It is very likely that residual components in the rags during different eras and in different locations would have had a bearing on the chemistry of subsequent steps in papermaking, the nature of the finished paper, and the changes in paper quality and character through the centuries. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to investigate this question during this research. For the moment it remains a potential variable worthy of further attention. Whatever their specific provenance, these rags, with their unique history before arrival at the paper mill, are the main reason that the better papers of the period can never be duplicated.

Retting

Retting is perhaps the least appreciated step in the early craft of papermaking. Its widespread disappearance between the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth-centuries may account for the general lack of attention to the process and to those responsible for it in contemporary discussions of hand papermaking. But its importance to the craft at earlier dates was evident to Lalande:

The fermentation, or retting, makes the paper uniform, binding, soft and gives it weight; if stopped too soon, the paper becomes coarse, hard, light and stiff, . . . [and the pulp] needs much more time to be worked; the starch [pulp] flies about and settles far less readily; it is a “wild” material in papermakers’ terms [it forms a less even, less uniform sheet].

If, on the other hand, the rags were left to ferment too long, there would be, as far as the papermaker is concerned, a considerable wastage.

The rettery constitutes a fundamental part of a papermill; in Auvergne the standard of the mill is judged by this. The room must be vaulted for the sake of cleanliness; the more it is protected from variation in temperature, the less the manufacturer is liable to error in the time necessary for correct fermentation; and because of this the process is neither interrupted nor hurried.24

Considerable skill and experience were required to evaluate the strength of the rag and the degree of retting required to produce fibers that would respond readily to stamping yet yield an optimum-quality sheet, with minimal loss of fiber. In the more substantial and well-established mills, fermenting was the job of a specialist, who passed his craft on to his sons or other young artisans. Knowing how to ret rags was not unlike knowing how to ferment grape juice to make good wine. Our knowledge of wine making, and our respect for it, is still considerable because we have seen fit to preserve the art. If we were able to travel back in time to the age of rag fermentation for papermaking, the man in charge in a good mill would have skills that were at least as highly respected as those of the man in the same town who made good wine. Over the ages, the art of making wine in the old way has sadly, but perhaps naturally, proved to be closer to people’s hearts than the making of good paper the old way.

The fermentation methods used by various mills are very likely to have differed as much as the construction and location of the mills themselves. Citing the fermentation routine at a particular mill is therefore a bit risky but probably worthwhile in light of our general lack of exposure to the technique. Lalande offers descriptions of several approaches:

In certain parts of Auvergne . . . the rettery is no more than a large basin of dressed stone for the fermentation and, so to speak, the rotting of the rags; it can be up to sixteen feet long by ten feet wide and three feet deep; the sides are cemented, but not the bottom, and the water thrown on the rags that this basin . . . contains can drain away by itself. . . . When the retting tank is full of rags, water is thrown over them until the tank is full [and is then allowed to drain] over a period of ten days, eight or ten times a day, without stirring. They are then left alone for another ten days approximately, without being watered; they are turned and the centre is brought to the surface to help the fermentation; when they have been turned, they are again left to ferment for fifteen to twenty days with the result that the rotting-down process can last up to five or six weeks; there is no fixed time limit, but when the heat has increased to the point where the hand can be left inside for a few seconds only, it is considered time to stop the process.

In the mills where there are but a few rags to be used, they are allowed to rot for a longer period, since the piles, being smaller, heat up less and with greater difficulty; so it is impossible to fix a precise duration for the retting process. It depends also on the quality of the cloth; the finer linen rots down less quickly than the coarser material and the old cloth with more difficulty than the new because the moisture content which predisposes the fiber to fermentation is greater in new or coarse cloth than it is in fine or old.25

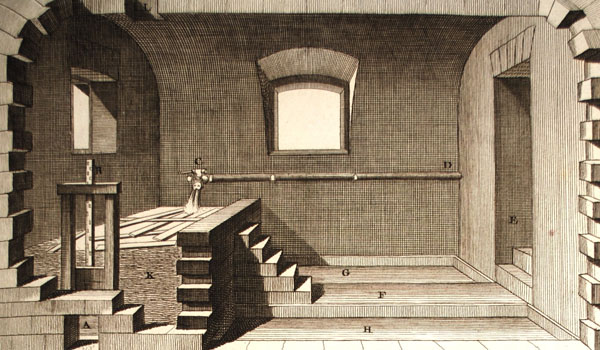

Figure 4. Rettery for fermentation of rags, which were pushed down from the sorting and cutting rooms above through the hole in the ceiling.

Lalande’s latter comment about the speed of the retting action (which he attributes to variations in moisture content of the rags) is of considerable interest. Pure cellulose is quite resistant to most bacterial and fungal attack, partly because of its inaccessible crystalline structure, but also because it lacks the nutrients sought after by most organisms, including those secreting cellulolytic enzymes. Newer or less fine linens and cloths may have fermented more quickly, as Lalande reports, simply because they contained components that acted as food for a larger organism population. No mention is made in the older references surveyed for this study of the addition of materials that may have acted as a “nutrient broth,” but, as suggested earlier, residual components in the old rags themselves may have played a key role in the ability of a pile of rags to support enzyme-secreting organism growth in a relatively short time.

Proteaux cites an enlightening 1813 French description by D’Arcet and Merimée, of the effects of retting:

The first change observed in the rags, after they have been for some time in the fermenting vat, is the disengagement of a material resembling mucus, so sparingly soluble in water that it is not removed in triturating the rags, and is even found in the vat at the time of manufacturing the paper. Pulp, produced by rags thus prepared [insufficiently fermented?] retains water, so that the paper made of this material shrinks very much in drying and in consequence has neither the weight nor the size which it should have. This mucosity is more abundant in proportion as the rags are coarser, as they have been less thoroughly washed before rotting and as the air of the fermenting vessel is more stagnant. This substance decomposes as the putrefaction advances, and gives rise to a kind of white mildew, similar to that which is seen on manure; and by that time a considerable portion of the rag fibers have been reduced to mold. In regard to the quantity of water which this mucous substance in the pulp will retain, the paper resembles that made from tow, containing a great deal of gluten. Fermentation facilitates trituration by destroying the glutinous materials which unite [or are present in] the rag-fibers.26

The “mucosity” referred to here may suggest the presence of a by-product of fermentation that acted as an antiflocculant or a formation aid. Such a component in fermented pulps would help explain the excellent knot-free formation seen in some higher-quality sheets.

While each mill certainly had its own resident population of organisms adhering to rettery walls from countless previous rets, the only artificially introduced starter or catalyst commonly mentioned in historical references as an aid to fermentation is lime. As an alkali, lime served to swell the cellulose, opening it up and making it more susceptible to chemical action by the enzymes secreted by the organisms present during the fermentation. Lime may have also encouraged the growth of microbes that favored the higher pH range. Whatever the chemistry, lime so effectively contributed to the speed of the ret that it was outlawed by regulation in some areas. Curiously, in complete contradiction to Lalande’s warnings about lime, D’Arcet and Merimée writing in 1813, described the use of lime to stop, rather than to accelerate, fermentation:

Lime, it is well known, has been employed at all times in our [French] paper-mills, and in some of them is so at the present day, not, however, to macerate the rags, but on the contrary to arrest the effects of maceration. When some circumstance has given rise to long delay the rags are taken out of the fermenting vessel, where they would not remain long without turning into mold, and dipped into a milk of lime. The material, when thus prepared, can be kept indefinitely. The same means are also employed to preserve the pulp, while in the condition of half-stuff.27

This approach and view more closely match my use of a slaked lime, Ca(OH)2, cook to stop a fermentation of new raw-flax fiber, kill microbes and most spores, counter the acidic pH of the ferment, and leave a residual compound that eventually will act as an alkaline reserve in the form of calcium carbonate.28 The contradictory views on lime mentioned above may be related to historical reporter or translator confusion over the form of lime employed. The more aggressive quicklime, CaO (calcium oxide), would have given much more action on the fiber than a slaked lime, Ca(OH)2 (calcium hydroxide), or old slaked lime which may have long since changed to the benign CaCO3 (calcium carbonate, limestone, or chalk).

With the possible exception of some form of lime, in most mills the only catalyst was apparently the leftover resident ‘starter’ from the previous fermentation. It is very likely that this was a distinctive population that evolved at each mill over many decades of repeated ferments. While early voices are generally silent on the matter, papermakers at later dates wished for an alternative to retting. Lalande lists several advantages to doing without the step:

If it were possible to destroy the strength and weave of the material and to degrease it without corrupting the substance by rotting, if one undertook the task of reducing the rags to pulp without fermentation, the paper would be stronger, less brittle and whiter. Some manufacturers say that retting gives, at least to the surface of each rag, a yellowish tinge that the mill eradicates only with difficulty and cannot eradicate completely if the material is too far gone.29

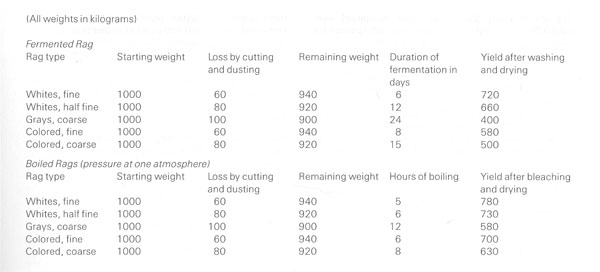

Cooking and bleaching, the modern substitution for fermentation and washing during beating, apparently came into use in Europe in the early nineteenth century. In the only such reference known to me, Proteaux cites work by Louis Piette and reprints his actual comparisons of the yields of different grades of fermented versus cooked rags.30 The same table is reproduced here as figure 5 below.

Figure 5. Piette’s comparison of yields from fermentation versus cooking.

The data here show a clear yield and time advantage to the cooking approach (chemical and concentration not given), but no mention is made of the effects of the two techniques on paper quality (paper permanence, durability, performance in use, and character).

Whatever the losses, the fermentation step was crucial to the early craft. It weakened the fiber and left it more readily shortened and fibrillated at beating, it helped cleanse the rags by ridding the fiber of noncellulosic impurities, and it played a key role in determining the quality and character of the finished paper.31 As mentioned above, chemical cooking and bleaching are used today to produce similar effects, but after fiber selection, Hollander beating is the key controlling factor used by the contemporary hand papermaker to determine the nature of the finished sheet. Relatively short variations in beating times can produce radically different papers from the same fiber. During most of the 1300–1800 period, however, fermentation was, after fiber selection, the key tool in the papermaker’s hand. Beating (by stampers) played an interrelated but secondary role.

Contemporaneous descriptions of the difference between paper made with fermented versus unfermented fiber can be found in work by Desmarest and other French writers who sought explanations for what they considered to be the superior quality of Dutch papers of the late eighteenth century. One key difference was that the Dutch papers were made from unfermented rags, since the Hollander beaters were able to work the rag fiber to the proper length without preliminary fermentation treatment. In describing differences in the papers at the sizing vat, sheets made from fermented pulps were considered weak and tender or “flabby” and “impermeable.”32 There are contradictory comments with regard to absorbency, as sheets made of fermented fiber were sometimes also considered too absorbent, requiring much more size than sheets made of unfermented Hollander-beaten fiber.33 It appears that whereas insufficient fermentation left sheets very impermeable, overfermentation left them too highly absorbent, and either extreme could complicate the application of size. The Dutch sheets, on the other hand, took the size slowly but kept it very tenaciously during pressing and exchanging.

Late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century criticism aside, the sensitive use of retting is a crucial reason for the unique look, feel, and handle of many of the best early book papers—comparable in importance to the use of gelatin sizing and loft drying, and second in importance only to the special nature of the old-rag raw material. The more subtle effects of retting on the fiber and its subsequent contribution to sheet forming, bonding, and the mechanical properties of the finished sheet remain to be investigated. In the meantime, the masterful use of retting in fiber preparation must be considered a lost art and one well worth learning again.

Intermediate Steps

Before proceeding with a discussion of beating, it is worth noting Lalande’s reference to two steps that often preceded beating: cutting and washing. The rags, many of which were fermented in their full original size, were cut into pieces no larger than two inches in any dimension to facilitate the action of the stampers. Washing the rags by hand in fresh water followed in some, but not all mills that Lalande observed. The latter step was often dispensed with because of the thorough washing accomplished during beating.

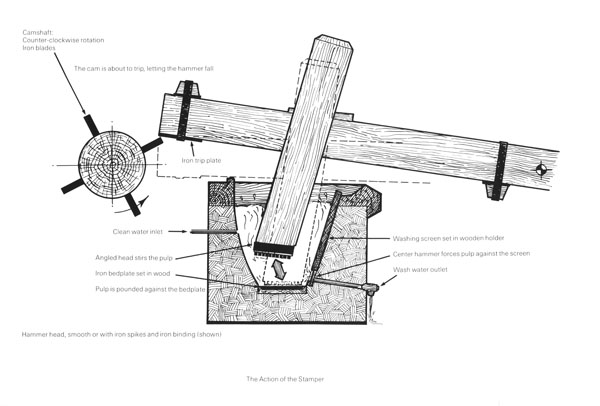

Stamper Beating and Washing during Beating

Much attention has been given to the early routine use of stampers. The Hollander beater (figure 15) was invented sometime between 1650 and 1680, but it was probably not until 1740 or 1750 that it replaced stamper beating in most mills in Europe. Even at that date, many papermakers stuck to their old stampers for reasons of tradition or cost.34 There was a belief then, as there is now, that the stampers made pulp that yielded a better paper. The commonly cited reason is that stamping left the fiber longer, and research on fiber length undertaken during the 1989 project tends to support this notion.35 Fiber length in that study decreased during the period between 1400 and 1800, in good and poor papers alike.

(Other reasons for the long life of paper made from stamper-beaten fiber should, of course, also be considered and would include favorable pH and residual metals, better-quality raw materials and more careful workmanship).

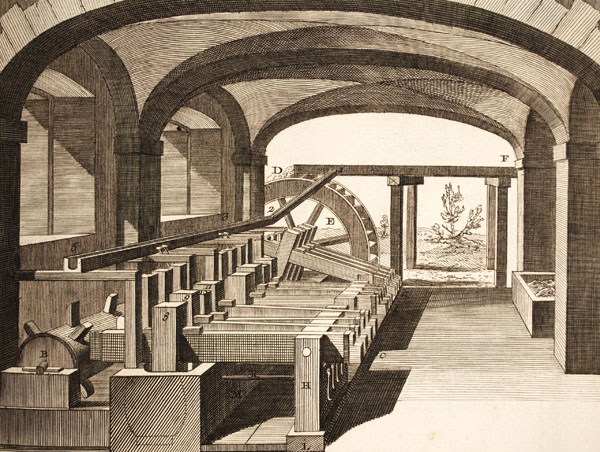

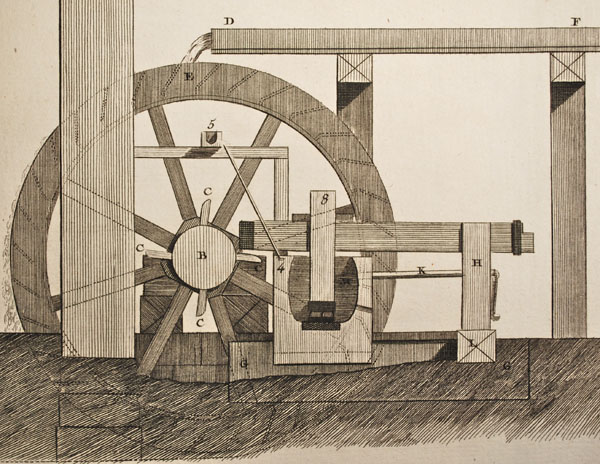

Figure 6. Diderot Encyclopédie stampers showing perspective view.36

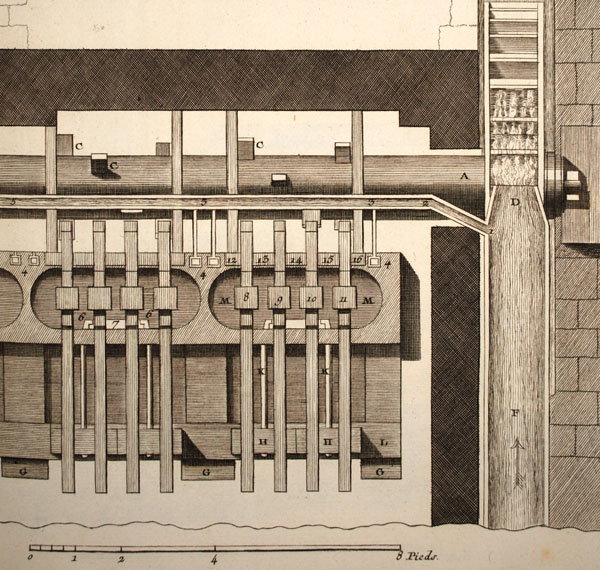

Figure 7. Encyclopédie stampers; top view.

Figure 8. Encyclopédie stampers; cut-away side view.

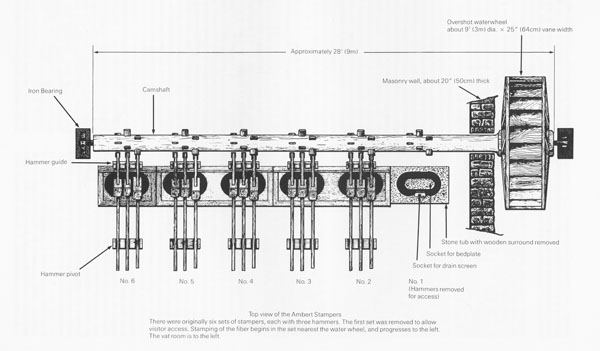

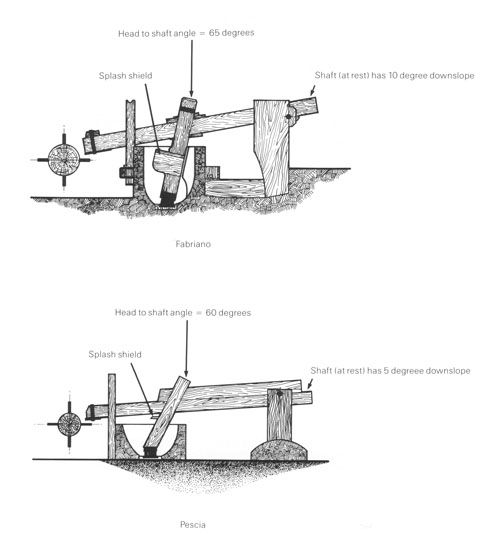

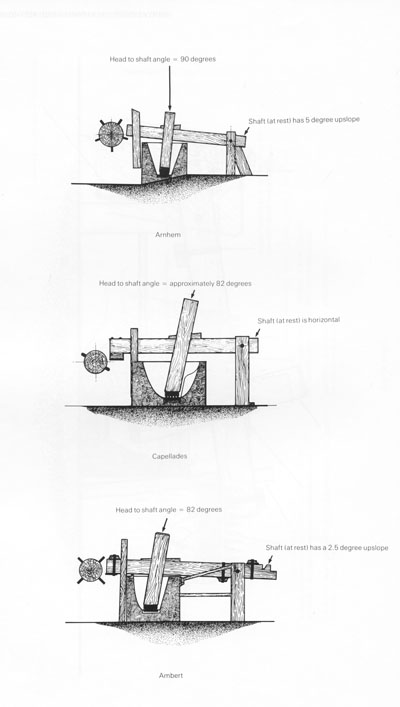

One of the best sources for studying early stampers are the few sets of such equipment still extant at various locations in Europe. Such a study has been one of the key areas of interest of Dr. Richard L. Hills, of the International Association of Paper Historians, whose work has proved extremely helpful to this research.37 Dr. Hills generously agreed to have his previously published drawings redrawn in more detail by Howard Clark of Twinrocker Handmade Paper.38 They appear as figures 9-14 below.

Stamping equipment, like waterwheels, varied considerably depending on the country, locale, date, and the skills and background of the millwright or builder. Attempting to accurately describe the average or generic stamper setup is therefore largely futile, though necessary in any attempt to understand the general workings of the machines in more detail. The images found in numerous older references are helpful but rarely detailed enough to tell the whole story.

It is hoped these drawings will serve to clarify some questions about stamper construction and operation. It must be emphasized, however, that exhaustive drawings of these sites have yet to be made and that the images shown here are composites based on field sketches of selected pieces of equipment. They are intended to represent some of the equipment in use between 1400 and 1800.

The drawings below should be considered in combination with a review of the operational set of full sized stampers masterfully constructed in 2009 by Jacques Bréjoux, Principal Papermaker of the Moulin du Verger (papermill) in France.39

Figure 9. Richard de Bas stampers, Ambert, France; top view.40

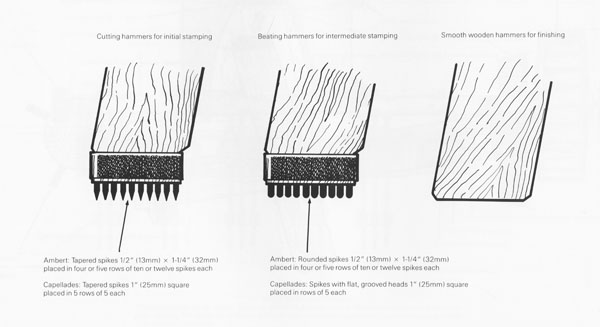

Figure 10. Stamper and nail head configurations.

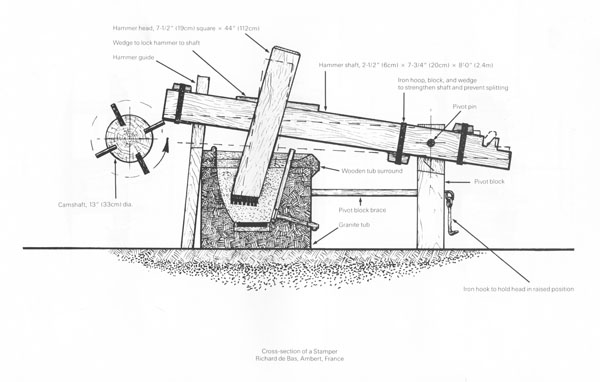

Figure 11. Richard de Bas stamper, cross section.

Figure 12. Richard de Bas stamper, cross section showing stamper action.

Figure 13. Variation of stamper head angles by location.

Figure 14. Variation of stamper head angles by location.

The superior condition of certain papers from earlier dates (1400–1500) has led some to speculate that stampers from that period were not shod with iron. Most historians seem to feel, however, that iron or possibly bronze “tackle” (stamper nail heads and bedplate) was a fairly early innovation (possibly circa 1300) and that between 1400 and 1800 it was much more the rule than the exception.

The general setup was to have separate pits or “troughs,” each fitted with three or more hammers. The hammers in a particular trough were all faced with tackle intended to accomplish a specific job. The first set of hammers was often shod with nails with rather aggressive heads designed expressly to cut the pieces of rag into smaller bits, a process often referred to as “breaking.” At the Papermill Museum in Capellades, Spain, spare nails still exist that show a distinct taper to a very narrow and sharp leading edge. Breaking stamper heads, like those in subsequent trough sets, worked against a bedplate of cast or wrought iron. With rags and water in place, of course, the head rarely, if ever, came in contact with the bedplate.

One of the more revealing aspects of Dr. Hills’ and Lalande’s work concerns the apparent attention to circulation of stuff in the trough. It seems clear that, at least in the more advanced mills, a number of details were designed specifically to promote the constant circulation, and therefore even treatment, of the rag fiber. Trough shape, hammer-head angle, hammer size, striking order of the heads, individual hammer lift distance and the consistency of the stock in the trough were all taken into consideration, monitored and altered to improve the work in hand. Dr. Hills’s research makes a clear case for the slanted positioning of the stamper head at many locations. Subsequent supportive work by Howard Clark on the stampers in figures 11 through 14 indicates a considerable increase in head swept volume (and therefore pulp circulation) as the hammer angle is increased.41

Measured amounts of rags were fed into the first trough, a little at a time, according to Lalande, in order that they might not choke up and bind together.42 Once the rags had been well cut and at least partially separated into threads in the first trough, the entire lot was transferred by hand to the second trough, where the hammers were fitted with more rounded or flat, broad-headed nails designed not to cut but to fray and separate the remaining bits of rag and threads into the individual cellulose fibers required for papermaking. The latter part of the treatment in the second set of stampers softened and plasticized the fiber, and raised short, fine fibrils from the main fiber surface (fibrillation). These latter effects were greatly facilitated by the retting pretreatment. As suggested earlier, it is my suspicion, although it has not been demonstrated, that the superb formation quality evident in many of the best early papers may have been a result of self-dispersive constituents that remained in the fiber as by-products from retting and began to take effect during stamper beating.

In the third type of trough, the faces of the hammers consisted only of plain wood. Their purpose was to brush, loosen or “liquefy” the pulp, by freeing it of flocs, especially if it had been left standing or concentrated for a time. In most mills, Lalande tells us, there were usually six troughs, three for breaking, two for beating and one for brushing out. He also tells us that each hammer struck forty blows a minute when the mill was running well.43 Relatively greater space was required for breaking, probably because the rough rags required more water to circulate properly. Breaking took six to twelve hours and beating another twelve to twenty-four hours or more, depending on the strength of the material.44 In this study no figures have been calculated for estimated consistency (percentage of fiber in water), but it is clear that fluid movement of the fiber in the trough was essential. Jacques Bréjoux reports working consistencies in his stampers of 5.6% to 6.7% (56 g to 67 gr per liter of water) depending on the nature of the rags, the degree of fermentation, and the stage of the beating.45

In some mills with irregular supplies of water, a large amount of breaking was accomplished during the winter and spring floods when water power was plentiful. The resulting “half stuff” was stored in stuff chests and the beating proper was completed later, just prior to papermaking.46 Fiber might also be pressed free of excess water and kept to mellow for shorter periods before preceeding to the next step.47

As beating progressed in the breaking and beating troughs, the fiber was being constantly washed with fresh water.

This step, like fermentation, is one of the less acknowledged but essential techniques in the early process. Clear water was led into the troughs by a system of wooden gutters and channels and the dirty water let out at the same rate through a horsehair net in the wall of the stamper trough. A good deal of water was made to pass through the fiber during the long breaking and beating periods required. It seems, in a way, odd that the fine white rags that formed the raw material for making higher-quality papers would have required such continuous washing to yield a fine white finished sheet. But strong detergents with optical whiteners were not available at the time, and it is more than likely that the rags were not that light in color to begin with. Many were soiled and, as mentioned above, the retting process left the rags with a yellow tinge that papermakers always sought to remove. Because they did not have strong cooking chemicals or bleaches that would quickly yield the desired brightness, washing surfaced as the standard procedure.

The addition of a white pigment such as ground limestone, chalk or sea shells would seem to have been a possible alternative, or an additional lightening technique. Based partly on the high levels of calcium detected in some specimens, and partly on their feel and appearance, it is my opinion that such materials were occasionally added, but the practice appears rare compared to the routine use of washing.

A side benefit of washing may have been its tendency to reduce drastically the population of spore-forming microbes remaining in the rag after fermentation. When paper specimens made in the laboratory (for the 1989 research) of retted or cooked raw-flax fiber were cut into 5 x 6 mm samples and exposed to a nutrient media, the samples that had received continuous washing during beating showed little or no bacterial growth compared with their unwashed counterparts.48 Of five historical specimens in good condition in the same experiment, only one showed any inclination to produce growth (although their considerable ages were certainly a factor).

In short, washing during beating appears to have been a key aspect of the early process that not only lightened the color of the finished paper but also very probably cleansed the fiber of impurities and microbes, permitted absorption of concentrations of calcium and magnesium carbonate (when they occurred naturally in the water) and removed a certain amount of fines, thereby improving drainage and raising the concentration of longer fibers.

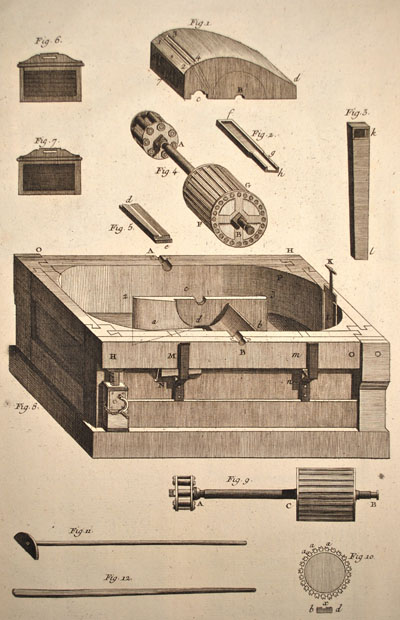

Figure 15. Hollander beater, Diderot Encyclopédie.49

The Hollander beater, a Dutch invention from the mid-seventeenth century, was designed to use windmill power and replace the heavy water wheel powered stampers that had been the standard in the papermaking trade across Europe for at least three centuries before. Rags and water were placed in an oblong tub fitted with a partition that ran along the center of its length. When power was applied the beater roll turned and pulled the rags beneath it where they were caught between the bars on the roll and the “bedplate;” another set of bars mounted permanently in the bottom of the tub. The rags circulated continuously around the tub as the bar to bar shearing action cut the rags into smaller pieces, the smaller pieces into individual threads, and the threads into fibers. Eventually the roll was lowered to shorten the fiber and fibrillate its surfaces, softening and plasticizing it at the same time. Less beating, whether in the Hollander or in the stampers, gave a more opaque, softer and weaker sheet while more beating gave a less opaque, harder, crisper, and stronger sheet.

Regarding the debate about stamper versus Hollander beaten fiber, in fact, in the hands of a skilled beaterman, a Hollander beater could be used to produce a paper with fiber as long, or longer than that produced in stampers employing the same raw material. The “fault” of the Hollander, if we choose to call it that, was in its substantially improved beating action, in particular its cutting ability. In the hands of an incompetent, or someone urged to get the job done faster, it makes it much easier to spoil an otherwise good fiber. The stampers, on the other hand were slow, and unlike the Hollanders they could not be adjusted to give a more aggressive, faster cutting action if desired (unless the pulp was beaten at a lower consistency, which would have been uneconomical). In any mill attentive to the financial realities of running a business, stamper time had its set cost. In brief, fiber was not allowed to remain in the stampers any longer than was necessary to gain the formation quality required for a given grade of paper. The gelatin size added to the finished paper made the more significant contribution to strength. The upshot of the matter was that stamper-beaten fibers very likely tended to remain longer in length than those produced in Hollanders. An unfortunate negative influence