- 27 Dec, 2025 *

Multi-tenant platforms which facilitate e-commerce transactions hold people’s money. Getting that money to the right people, in the right amounts, at the right time, is the core trust contract with your partners. This is the most critical and sensitive component in our system as if it fails, trust erodes quickly.

We needed a payment engine that could collect funds from multiple sources, track what’s owed across different transaction types, batch payments to minimize fees, and handle the messy reality of refunds, multi-currency, and timing mismatches.

This post covers how we:

- Implementing double-entry bookkeeping in software: advantages, challenges, and key design decisions

- Database schema design for ledgers, transactions, and journal entries

- Transaction st…

- 27 Dec, 2025 *

Multi-tenant platforms which facilitate e-commerce transactions hold people’s money. Getting that money to the right people, in the right amounts, at the right time, is the core trust contract with your partners. This is the most critical and sensitive component in our system as if it fails, trust erodes quickly.

We needed a payment engine that could collect funds from multiple sources, track what’s owed across different transaction types, batch payments to minimize fees, and handle the messy reality of refunds, multi-currency, and timing mismatches.

This post covers how we:

- Implementing double-entry bookkeeping in software: advantages, challenges, and key design decisions

- Database schema design for ledgers, transactions, and journal entries

- Transaction states, batching strategy, and idempotency

- The complete payout pipeline from event completion to funds disbursement

- Extensibility: how the system accommodates new transaction types cleanly through extension

The Business Problem

Paying People Accurately and On Time

Event organizers, comedians, and venue partners rely on receiving exactly what they’re owed, when they expect it. Someone who performed on Saturday expects their cut by Tuesday at the latest, as cash flow in the industry is generally tight. We are dealing with people’s livelihoods and they have trusted us with one of the most important parts of their business: selling shows and collecting funds.

Money Flows Both Directions

Customers buy tickets (revenue flows in), but accounts also purchase card readers, run ads, or get charged service fees (charges flow out). Meanwhile, they earn referral bonuses and tips. The net result: at any given moment, someone either owes us money or we owe them and this account needs to be settled cleanly. Often times clubs have multiple shows where different accounts need to be paid even though all the performances were at the same club.

Minimizing Transaction Costs

Tipalti, our disbursement provider, charges $2.10 per outgoing payment. If we paid each transaction individually, we would bleed money as 50 payouts would cost us $105 in fees, making the business model untenable. Batching them into one payment at the right time and covering a reasonable span of transactions is key to minimizing transaction costs. Across hundreds of accounts paying out weekly, this compounds into significant savings, but this has to be balanced with timing.

Multi-Currency, Multi-Region Support

Events happen in USD, CAD, GBP, EUR. An organizer in London running shows might have ticket sales in pounds and euros, or if they’re Canadian, in CAD. We must track revenue per currency, convert correctly, and pay in their preferred currency. Tipalti handles the actual disbursement mechanics, but we must get the numbers right.

One Invoice, Many Line Items

An organizer’s weekly payout isn’t just "event revenue." It might include:

- Event ticket sales: +$500

- Tips earned: +$45

- Service fee split: +$30

- Card reader purchase: -$75

- Meta ad spend: -$120

- Net payout: $380

All of these must appear on the same statement, clearly itemized.

The Refund Timing Problem

A customer requests a refund on Monday. The event happened Saturday. We already paid the organizer on Sunday. That refund must be accounted for retroactively—deducted from their next payout—and clearly tracked so they understand why this week’s payment is lower.

Why Not Off-the-Shelf?

Payment platforms like Stripe Connect handle simpler splits, but our requirements of having multiple transaction types flowing both directions, batched payouts to external payment processors, multi-currency with conversion, and retroactive adjustments, require a purpose-built accounting layer.

We explored Stripe Connected Accounts feature but payment processing delays, and Stripe’s unintuitive Connected Account interface was causing a lot of confusion for customers. Their onboarding process was also problematic and often required manual intervention which our customers found annoying. We also explored paying people using services like Interac E-Transfer but hit usage limits very quickly.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping & Key Design Decisions

Why Double-Entry?

We took our inspiration from Square and the Payments Engineer blog which have some guidance on how to think about the complexity tradeoffs that double-entry bookkeeping presents. In short, it’s worth it if you can reason about it.

Every money movement creates balanced journal entries. If cash increases (debit), accounts_payable increases (credit). The books always balance, providing an immutable audit trail and catching errors immediately. This is an unintuitive approach unless you’re an accountant or in finance, but it creates immutability and an audit trail of what happened and why.

By thinking about money movements as inflows and outflows in certain ledgers, rather than the maintenance of a specific balance, we’re able to "replay" history more easily and derive rather than store balances.

Advantages and Challenges in an IT System

Though double-entry bookkeeping is much more complex to implement than maintaining a simple balance amount, it has its clear advantages:

Self-validating — If debits don’t equal credits, something is wrong. No silent data corruption. Your accounting becomes intrinsically verifiable by examining individual transactions and the ledgers they impacted, rather than reverse-engineering why a balance is what it is.

Complete temporal audit trail — Every cent is traceable to its source transaction. Every money movement is the result of something changing, and that something is reflected as a transaction. The transaction stores what’s changed, not the current state, so we can always ask the question "what as the balance three days ago" because we’d examine the "projections" (CQRS anyone?) up until three days ago.

Flexible reporting — Generate balance sheets, cash flow statements, and account summaries from the same data becomes easy due to the comprehensive audit trail.

Refunds are natural — A refund is simply the reverse entry pattern. No special logic needed. We just increment/decrement (or debit/credit) in the opposite manner.

And challenges:

Cognitive overhead — Developers must think in debits/credits, not just "add money" or "subtract money." This is not an easy hurdle to get past, and having a good understanding of core accounting principles helps (I did an MBA a while back and that came in handy here).

Schema complexity — More tables, more joins, more migrations than a simple balance column.

Query complexity — Calculating a balance requires summing journal entries, not reading a single field. It is easy to get the queries wrong if you don’t understand how a "purchase" vs a "charge" is recorded, i.e., what ledgers are modified and how.

Eventual consistency concerns — Must ensure both sides of an entry are written atomically (solved with database transactions). And in cases where transactions span network boundaries, compensation is required. In our case, using the Reactor library.

Database Design & Data Model

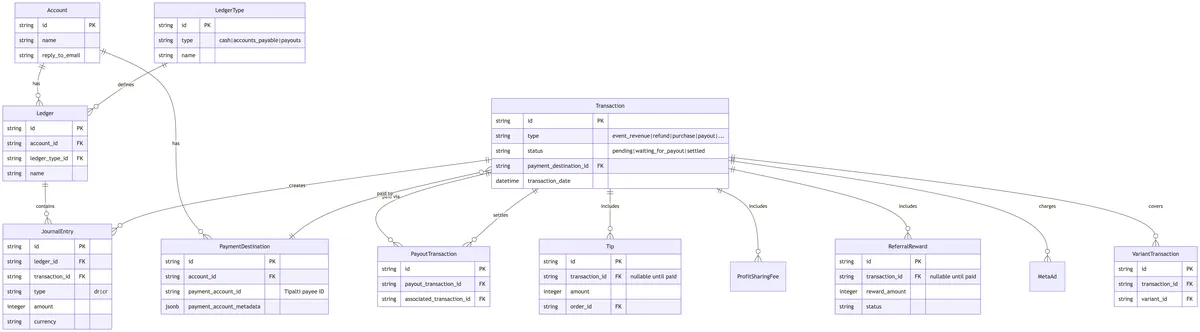

Here’s the key elements of the data model and a brief description, more on this in the later sections:

- Account - a user’s account in the system

- Payment Destination - something like PayPal, a bank account

- Tip, MetaAd - business objects which demand a need for payments

- Transaction - models a singular business money movement

- LedgerType - an accounting book, e.g., accounts payable

- Ledger - an accounting book for a particular account

- PayoutTransaction - shares the same physical table as Transaction (with a different type) but models outgoing money movements and is composed of other transaction types (e.g., event revenue). This is a powerful concept in the system.

Entity Relationship Diagram

Transaction Types and Journal Entry Patterns

| Transaction Type | Debit | Credit | Business Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| event_revenue | cash | accounts_payable | We collected ticket sales, owe organizer |

| tips_earned | cash | accounts_payable | We collected tips, owe organizer |

| gift_card_revenue | cash | accounts_payable | Gift card redeemed for event |

| service_fee_split | cash | accounts_payable | Organizer’s share of service fees |

| customer_cashback | accounts_payable | cash | Referral reward owed to customer |

| refund | accounts_payable | cash | We refunded customer, owe organizer less |

| purchase | accounts_payable | cash | Organizer bought something (card reader) |

| ads | accounts_payable | cash | Ad spend charged to organizer |

| payout | payouts | cash | We disbursed funds to organizer |

Core Bookkeeping Function

defp create_journal_entry(ledger, transaction, entry_type, %{

"amount" => amount,

"currency" => currency

}) do

%JournalEntry{

ledger: ledger,

transaction: transaction,

type: entry_type,

amount: amount,

currency: currency

}

|> Repo.insert!()

end

This simple function is the foundation of the entire system. Every money movement flows through it.

Transaction States, Batching & Idempotency

Finite State Machine for Transactions

Most transaction types, for example event_revenue which represents money earned from an event follows this (simplified) pattern:

pending → waiting_for_payout → settled

- pending — Transaction recorded, awaiting payout batch

- waiting_for_payout — Included in a payout batch, not yet sent

- settled — Payment executed successfully

States prevent double-payments, enable clear reporting ("what’s been paid vs pending"), and allow recovery if processes fails mid-batch. Being in a particular state implies that all previous rules concerning that state have been satisfied. For example, if a transaction of type event_revenue is in waiting_for_payout we can assume that the total payment amount has been calculated, the account has not been paid, and will be paid on the next scheduled run. These are corollaries of a transaction of a particular type being in a particular state.

The combination of transaction type plus transaction state gives us a very clear view on how the money is moving.

The Batching Algorithm

To minimize transaction costs, handle multi currencies, and allow the same account to have funds dispersed to many different bank accounts, we batch the transactions and introduce the concept of a payment_destination which has many-to-one relation with an account.

The create_pending_payout_transactions/0 groups all pending transactions by (currency, payment_destination_id, account_id). Each group becomes one payout transaction, regardless of how many underlying transactions exist.

def create_pending_payout_transactions do

Repo.transaction(fn ->

# Fetch all pending transactions grouped by currency, payment_destination_id, and account_id

pending_transactions =

Repo.all(

from je in JournalEntry,

join: t in assoc(je, :transaction),

join: l in assoc(je, :ledger),

where:

t.status == "pending" and

t.type in [

"event_revenue",

"refund",

...

],

group_by: [fragment("lower(?)", je.currency), t.payment_destination_id, l.account_id],

select: {fragment("lower(?)", je.currency), t.payment_destination_id, l.account_id}

)

# Process each group to create a payout transaction

Enum.map(pending_transactions, fn {currency, payment_destination_id, account_id} ->

payout_amount = calculate_payout_amount(account_id, currency, payment_destination_id)

# ... create or update payout transaction

end)

end)

end

This is the central algorithm which looks at transactions and their journal entries, and calculates how much is owed to each account, and within each account, how funds must be disbursed to different payment destinations (e.g., PayPal, Bank).

Idempotency by Design

It is important that these processes are not time-dependent and can be run at any time without affecting overall amounts. Processes/jobs should be able to be run multiple times without negative consequences, i.e., they need to be idempotent.

create_pending_payout_transactions/0is idempotent—if a pending payout already exists for a destination, it updates the amount rather than creating a duplicate.- If a job fails and retries, or runs twice, the result is the same.

- No orchestration dependencies—event revenue, tips, refunds, and ads can be processed in any sequence. The batching step always queries current state and produces correct results.

transaction =

case Repo.get_by(Transaction,

type: "payout",

status: "pending",

payment_destination_id: payment_destination_id

)

|> Repo.preload(:journal_entries) do

nil ->

# Create new payout transaction

%Transaction{

type: "payout",

status: "pending",

payment_destination_id: payment_destination_id,

transaction_date: DateTime.utc_now()

}

|> Repo.insert!()

existing_pending_payout_transaction ->

# Update existing - idempotent!

Enum.each(existing_pending_payout_transaction.journal_entries, fn je ->

je |> Ecto.Changeset.change(%{amount: payout_amount}) |> Repo.update!()

end)

existing_pending_payout_transaction

end

Calculating Net Payout

Calculating payouts is all about consulting the accounts_payable ledger as that keeps track of how much money is owed to a customer:

defp calculate_payout_amount(account_id, currency, payment_destination_id) do

# Query total credits from accounts_payable ledger

credits_query =

from je in JournalEntry,

join: t in assoc(je, :transaction),

join: l in assoc(je, :ledger),

join: lt in assoc(l, :ledger_type),

where:

je.type == :cr and lt.type == "accounts_payable" and l.account_id == ^account_id and

fragment("lower(?)", je.currency) == fragment("lower(?)", ^currency) and

t.status in ["pending", "waiting_for_payout"],

select: sum(je.amount)

# Query total debits from accounts_payable ledger

debits_query =

from je in JournalEntry,

join: t in assoc(je, :transaction),

join: l in assoc(je, :ledger),

join: lt in assoc(l, :ledger_type),

where:

je.type == :dr and lt.type == "accounts_payable" and l.account_id == ^account_id and

fragment("lower(?)", je.currency) == fragment("lower(?)", ^currency) and

t.status in ["pending", "waiting_for_payout"],

select: sum(je.amount)

credits = Repo.one(credits_query) || 0

debits = Repo.one(debits_query) || 0

credits - debits

end

Result can be positive (we owe them), zero (nothing to pay), or negative (they owe us—carried forward).

Key Design Decisions

1. Transaction Type Drives Journal Entries

We faced a choice: should the system rely on tracking events by creating specific ledgers for different transactions (e.g., tips, hardware purchases etc.) and then summing debits and credits, or by looking at transaction type and status? We chose the latter for its simplicity while .

Transaction type and journal entries are related but orthogonal concepts:

- Transaction type answers: "What happened?" (event_revenue, refund, purchase, payout)

- Journal entries answer: "How did it affect money movement?"

When creating a transaction, the type determines which journal entry pattern to apply:

event_revenue → DR cash, CR accounts_payable

refund → DR accounts_payable, CR cash

payout → DR payouts, CR cash

Alternately, we could have created a event_cash and event_payable book and examine those, but we found it overkill to reason about so many ledgers. Besides, we can always extend them at no cost. But querying WHERE type = 'event_revenue' AND status = 'pending' is far more intuitive than traversing specific journals based on type to reconstruct intent. Type alone is sufficient.

2. Bridging Accounting and Business Domains via transaction_id

Transactions are generic accounting records as they know about amounts, currencies, and ledger entries. But the business needs to answer questions like "which tips are included in this payout?" or "what ad campaigns does this charge cover?"

We solve this by adding transaction_id as a foreign key on business domain tables:

| Business Table | Links To | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

Tip | Transaction | Which tips were paid in this transaction |

ProfitSharingFee | Transaction | Which service fee splits are included |

ReferralReward | Transaction | Which cashback rewards were processed |

MetaAd | Transaction | Which ad charges are covered |

VariantTransaction | Transaction + Variant | Which event variants generated this revenue |

This creates bidirectional traceability:

- Accounting → Business: Given a transaction, find all the tips/ads/rewards it covers

- Business → Accounting: Given a tip, find which transaction (and ultimately which payout) included it

When creating a transaction, we update the business records:

# In create_tips_earned_transaction

Repo.update_all(

from(t in Tip, where: t.id in ^tip_ids),

set: [transaction_id: transaction.id]

)

This means payment summaries can show "Tips from 12 orders: $45" with full drill-down capability.

3. Per-Account Ledgers, Not Global Ledgers

Each account gets its own set of ledgers (cash, accounts_payable, payouts). We chose per-account because:

- Queries for account balances are simpler

- Natural isolation between accounts

- Ledger-level reporting is account-scoped by default

setup_ledgers(account_id)lazily creates ledgers on first transaction—no upfront provisioning needed

4. Payment Destination as the Batching Key

Transactions are grouped by (currency, payment_destination_id, account_id), not just account. This allows:

- One account to have multiple payment destinations (UK bank for GBP, US bank for USD)

- Different payout schedules per destination if needed

- Clean separation when an account changes bank details mid-cycle

- Allows for different events to be paid to different payment destinations within the same account

5. Amounts in Cents as Integers

All amounts are stored as integers representing the smallest currency unit (cents, pence). No floating point arithmetic means no rounding errors accumulating across thousands of transactions.

6. Status Lives on Transaction, Not JournalEntry

Journal entries don’t have independent status—they inherit from their parent transaction. This avoids the complexity of partially-settled transactions and keeps state management in one place.

7. Join Table for Payout Associations

Rather than adding payout_transaction_id to the Transaction table, we use a separate PayoutTransaction join table. This:

- Preserves the original transaction record unchanged

- Allows a transaction to theoretically be part of multiple payout attempts (retry scenarios)

- Makes "what was included in this payout?" a clean query

8. Atomic Transaction Creation

Every accounting operation wraps in Repo.transaction/1. If creating the second journal entry fails, the first is rolled back. The books are never unbalanced, even momentarily. As mentioned earlier, the Reactor library is used to compensate/undo transactions when API calls to disbursement system fails.

Our Ledger Types

- cash — Money we hold (bank account)

- accounts_payable — Money we owe to organizers

- payouts — Money we’ve disbursed

The golden rule: Every transaction creates exactly two journal entries that sum to zero.

The Payout Pipeline & Execution

Payment Flow Sequence

sequenceDiagram

participant Scheduler as Oban Scheduler

participant EPM as EventPaymentMaker

participant AC as AccountingContext

participant TPM as TransactionPaymentMaker

participant Tipalti as Tipalti API

participant Mailer as Email Service

Scheduler->>EPM: create_event_revenue_transactions()

EPM->>EPM: Find payable variants (completed events)

EPM->>EPM: Find payment destination for each

EPM->>EPM: Calculate payable amount (with currency conversion)

EPM->>AC: create_event_complete_transaction()

AC->>AC: Create Transaction (status: pending)

AC->>AC: Create JournalEntry (DR cash)

AC->>AC: Create JournalEntry (CR accounts_payable)

AC->>AC: Link VariantTransaction records

Note over Scheduler: Similar flow for tips, gift cards, refunds, ads...<br/>Each updates business records with transaction_id

Scheduler->>AC: create_pending_payout_transactions()

AC->>AC: Group pending transactions by (currency, destination, account)

AC->>AC: Calculate net payout for each group

AC->>AC: Create/update payout Transaction (idempotent)

AC->>AC: Link via PayoutTransaction join table

AC->>AC: Mark source transactions as waiting_for_payout

Scheduler->>TPM: pay()

TPM->>AC: get_pending_payout_transactions()

loop For each payout transaction

TPM->>AC: settle_payout_transactions()

AC->>AC: Mark payout + associated as settled

TPM->>Tipalti: make_payment(amount, currency, payee_id)

Tipalti-->>TPM: batch_reference_id

TPM->>TPM: Record payout history

TPM->>Mailer: Send payment summary email

end

Scheduled Orchestration

An Oban worker runs on schedule, executing the full payout flow:

defmodule Amplify.ScheduledJobs.EventPayoutTipalti do

use Oban.Worker, queue: :event_payouts, max_attempts: 1

require Logger

@impl Oban.Worker

def perform(_args) do

Logger.info("Starting Creating Payout Transactions")

Amplify.EventPaymentMaker.create_event_revenue_transactions()

Logger.info("Finished Creating Event Revenue Transactions")

Amplify.GiftCardPaymentMaker.create_gift_card_transactions()

Logger.info("Finished Creating Gift Card Transactions")

Amplify.DigitalProductPaymentMaker.create_digital_product_transactions()

Logger.info("Finished Creating Digital Product Transactions")

Amplify.CustomerCashbackTransactionCreator.create_customer_cashback_transactions()

Logger.info("Finished Creating Customer Cashback Transactions")

Amplify.AccountingContext.create_pending_payout_transactions()

Logger.info("Finished creating pending payout transactions")

# Start ProcessAdPayments job to handle Meta ad billing

%{}

|> ProcessAdPayments.new()

|> Oban.insert()

Logger.info("Enqueued ProcessAdPayments job")

:ok

end

end

Payment Execution

TransactionPaymentMaker.pay/0 iterates pending payout transactions created earlier to disburse funds and update statuses:

def pay do

{:ok, result} = AccountingContext.get_pending_payout_transactions()

result

|> Enum.map(fn {account_id, payment_destination_id, transactions} ->

Repo.transaction(fn ->

Enum.map(transactions, fn transaction ->

amount = transaction.journal_entries |> List.first() |> Map.get(:amount)

currency = transaction.journal_entries |> List.first() |> Map.get(:currency)

payment_destination = Repo.get!(PaymentDestination, payment_destination_id)

{:ok, [%Transaction{} = payout_transaction]} =

case amount do

amount when amount >= 0 ->

AccountingContext.settle_payout_transactions([transaction.id])

_ ->

{:ok, [transaction]}

end

{:ok, batch_reference_id} =

case amount do

amount when amount > 0 ->

Tipalti.make_payment(%{

"amount" => amount / 100,

"currency" => currency,

...

})

_ ->

{:ok, nil}

end

if amount >= 0 do

Tipalti.create_payout_history(%{

payment_destination_id: payment_destination_id,

transaction_id: payout_transaction.id,

batch_reference_number: batch_reference_id,

amount: amount,

currency: currency

})

send_payment_summary_email(%{

payout_transactions: payout_transaction.payout_transactions,

batch_reference_id: batch_reference_id,

account_id: account_id

})

end

payout_transaction

end)

end)

end)

end

Handling Edge Cases

Post-payment refunds — Creates a new refund transaction that reduces the next payout automatically. The DR accounts_payable, CR cash pattern naturally reduces the amount owed.

Zero/negative payouts — No Tipalti call; balance carries forward to the next payout cycle.

Missing payment destinations — Skip and notify via email; transactions remain pending until the organizer adds payment info.

Extensibility: Adding New Transaction Types

The Model Accommodates Change

New revenue streams and charge types are inevitable. The system was designed so adding a new transaction type doesn’t require schema changes or breaking existing logic.

Adding a New Transaction Type Requires:

- Define the type string (e.g.,

"membership_fee") - Decide the journal entry pattern (revenue: DR cash, CR accounts_payable; charge: reverse)

- Create a function which creates a transaction using an established pattern

- Add the type to the batching query’s

type in [...]list - Optionally: add

transaction_idto a business domain table for traceability

Example: Adding Subscription Revenue

def create_subscription_revenue_transaction(%{"subscription_ids" => subscription_ids} = params) do

Repo.transaction(fn ->

setup_ledgers(params["account_id"])

transaction = create_transaction(params |> Map.put("type", "subscription_revenue"))

cash_ledger = get_ledger("cash", params["account_id"])

accounts_payable_ledger = get_ledger("accounts_payable", params["account_id"])

create_journal_entry(cash_ledger, transaction, :dr, params)

create_journal_entry(accounts_payable_ledger, transaction, :cr, params)

# Link to business domain for traceability

Repo.update_all(

from(s in Subscription, where: s.id in ^subscription_ids),

set: [transaction_id: transaction.id]

)

Repo.get!(Transaction, transaction.id)

|> Repo.preload([:journal_entries, :subscriptions])

end)

end

The batching and payout logic automatically picks it up and no changes needed downstream.

For variations within a type (e.g., differentiating "premium event" vs "standard event" revenue), we can always:

- Add a

subtypefield to Transaction - Store additional context in a JSONB

metadatafield - Link to domain-specific tables via join tables

The core accounting remains unchanged; subtypes are for reporting and business logic. More important than what needs to change is what doesn’t need to change when new payment requirements inevitably popup:

- Database schema (unless linking to new domain entities)

- Batching logic (queries by status, not type)

- Payout execution (reads journal entries, agnostic to transaction type)

- State machine (all types follow the same pending → waiting_for_payout → settled flow)

This has been tested thoroughly as since inception we’ve added support for the following transaction types cleanly:

- customer_cashback — Referral rewards paid to customers (reverse flow)

- ads — Meta ad spend charged to accounts

- service_fee_split — Revenue sharing with partners

Each took hours to implement, not days, because the foundation was solid.

Lessons Learned

1. Invest in the Foundation Early

Building double-entry bookkeeping felt like over-engineering initially. A simple balance column would have shipped faster. But when we needed to add refunds, then tips, then ad charges, then multi-currency, the foundation paid for itself many times over. Each new transaction type slots in cleanly instead of requiring architectural surgery.

2. Idempotency Is Worth the Complexity

Making operations idempotent required more upfront thought—checking for existing records, updating instead of inserting, querying current state rather than relying on sequence. But it eliminated an entire class of bugs: duplicate payments, orphaned records, and state corruption from retried jobs. When your system handles money, "ran twice by accident" cannot mean "paid twice."

3. Separate Accounting from Business Logic

The transaction_id foreign key pattern was a late addition. Initially, we tried to make transactions self-describing with rich metadata. But queries like "show me all tips in this payout" became convoluted. Keeping transactions as clean accounting records and linking them to business entities via foreign keys gave us the best of both worlds: simple accounting logic and rich business context.

4. Status Is Easier Than Ledger Math

We debated whether to derive "what’s pending" by summing ledger entries (the pure accounting approach) versus querying transaction status (the pragmatic approach). Status won. Developers can reason about status = 'pending' without understanding debits and credits. The journal entries remain the source of truth for amounts; status is the source of truth for workflow state.

5. Batching Is a Product Feature, Not Just a Cost Optimization

We initially thought of batching as purely an internal optimization to reduce Tipalti fees. But organizers love seeing a single weekly payment with a detailed breakdown rather than dozens of micro-deposits. The batching architecture became a product feature: predictable payment schedules with comprehensive statements.

6. Plan for Retroactive Adjustments

The refund-after-payment scenario seemed like an edge case but it’s actually quite popular. Chargebacks, late refund requests, and corrections happen regularly. Because every adjustment is just another transaction with the appropriate DR/CR pattern, the system handles them naturally. The next payout simply reflects the updated balance.

7. Currency Handling Is Subtle

We underestimated currency complexity. It’s not just conversion rates, it’s also case sensitivity (USD vs usd), timing of conversion (at transaction time vs payout time), and reporting currency vs payment currency. Using fragment("lower(?)", je.currency) everywhere and storing the payment destination’s preferred currency solved most issues, but we wish we’d been more deliberate from the start.

8. Traceability Saves Support Time

Every support ticket about payments boils down to "why did I get this amount?" Full traceability—from payout email → payout transaction → source transactions → individual tips/events/charges → original orders—means support can answer definitively instead of guessing. The join tables and foreign keys that felt like extra work during development save hours of investigation weekly.

Conclusion

Building a payment engine from scratch is a significant undertaking, but for multi-sided marketplaces, it may be unavoidable. Off-the-shelf solutions optimize for simpler flows like point-to-point atomic transactions. However, when money moves in multiple directions, across currencies, with retroactive adjustments and batched payouts, you need control over the accounting layer.

The key architectural decisions that served us well:

- Double-entry bookkeeping provides self-validation and an immutable audit trail

- Transaction types drive journal entries, making business logic explicit

- Linking accounting to business domains via

transaction_idenables full traceability - Per-account ledgers simplify queries and provide natural isolation

- Idempotent operations eliminate duplicate payment risks

- State machine for transactions makes workflow explicit and prevents double-processing

- Batching by payment destination minimizes fees while improving the organizer experience

The system has processed millions of dollars across multiple currencies, handled thousands of refunds (including post-payment adjustments), and scaled to support new transaction types as the business evolved. The upfront investment in a solid foundation made all of this possible.

If you’re building something similar, start with the accounting model. Get the ledgers, journal entries, and transaction patterns right first. Everything else like batching, scheduling, and notifications builds cleanly on top of a sound foundation.

Built with Elixir, Phoenix, Ecto, and Oban. Payment processing via Tipalti.