- 02 Dec, 2025 *

Introduction

This is continuation of the first series on using custom C header file (safe_c.h) to build a sizeable small program (2-3k loc) as an experiment related to DX and the final program result.

If the first series I put the focus on safe_c.h header file, in this second series I want to talk in depth on the final program result: cgrep. The thing is, there are plenty of angles I want to talk about especially because this has been a long chain reaction of investigation I did and in order to get the complete picture I will need to refer you to my past blog posts. These investigations I did in the end inspired me to build a (rip)grep clone.

[Fasta benchmarks game](htt…

- 02 Dec, 2025 *

Introduction

This is continuation of the first series on using custom C header file (safe_c.h) to build a sizeable small program (2-3k loc) as an experiment related to DX and the final program result.

If the first series I put the focus on safe_c.h header file, in this second series I want to talk in depth on the final program result: cgrep. The thing is, there are plenty of angles I want to talk about especially because this has been a long chain reaction of investigation I did and in order to get the complete picture I will need to refer you to my past blog posts. These investigations I did in the end inspired me to build a (rip)grep clone.

Fasta benchmarks game

I love doing benchmarks of all kinds, I have a knack for performance..I would fight for an extra millisecond faster program. Now imagine my shock when I found out some of the most popular benchmark websites (un)knowingly mislead people with their summary table. Read the article for the whole story but the essence can be summarized:

Summary tables from both websites shows Rust is #1 on the rank, as the saying goes: “Blazingly fast!”. The punchline: the Fasta Rust programs are both multi-threaded, while the C and Zig programs are single-threaded.

“What a blazingly ass comparison!” was my first thought and from there I went on a “witch hunt” for these kinds of misleading practices.

Levelized cost of resources in benchmark

In this article I pointed out the need to levelize or normalize resource cost / usage. It’s great to see program XY is almost 3x faster compared to program AB, but how do you feel if it’s at the cost of 8x more resource usage? Is it worth it?

I also underlined ripgrep github benchmark that unfortunately compared multi-threaded to single-threaded program, while ripgrep got the option to set -j1 (to make it single-threaded) but as you can check yourself, the benchmarks are not using the -j1 flag. Do you think it’s a fair comparison?

Another important point I made at the end of the article: doing benchmarks in quiet vs noisy system. This point of view inspires me in the later part of the article to split the cgrep vs ripgrep benchmark in both systems (quiet & noisy) as I think noisy system better simulates real usage environment.

The point I want to make:

When using a program (such as [rip]grep), do you close the other running processes first? Or would you just run the program ALONGSIDE other running processes? Exactly my point and hence the noisy system test is important as well coz some programs have deep performance regression when ran in a noisy system.

Compiler optimization options

This article serves as complementary coz it discusses a lot surrounding ripgrep.

cgrep : high performance grep

Written in C23, the program serves as my experimental project on using my custom safe_c.h header file with the purpose: “write C, get C++ and Rust features”. Someone posted the first article about safe_c.h on hackernews and it ranked #3 for a short while, what’s interesting was the discussion and I love reading those multiple different PoVs.

For my future C projects I will keep on using safe_c.h as it has become an invaluable tool for me and it has elevated my DX albeit the C I’m writing might seem foreign to some.

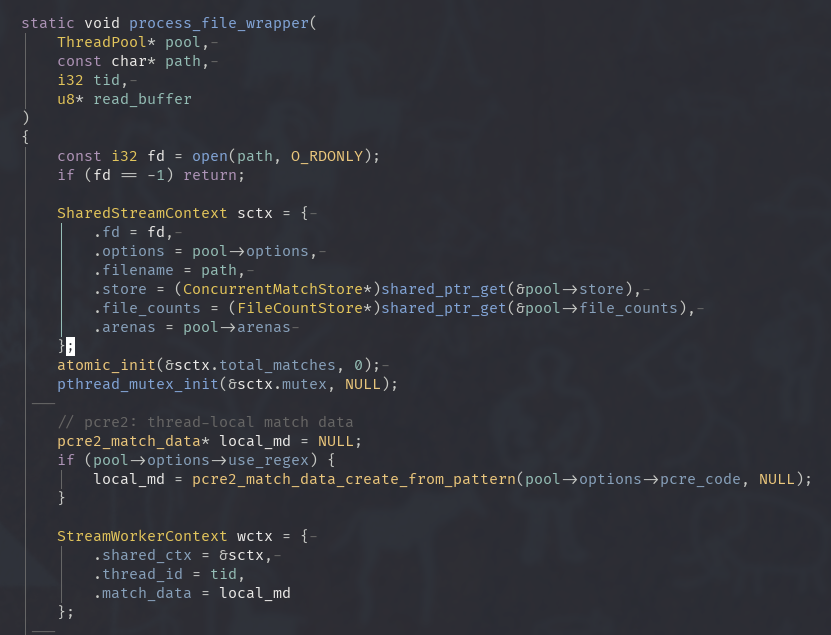

Check below one of cgrep’s function:

Main Workflow: a team of supercharged workers

Producer-Consumer multi threading model where one Producer scans directories while applying “smart filters” where it ignores dirs such as node_modules, .gitand puts valid file paths for the Consumer (worker threads) to process. It also applies back-pressure for a situation where the Producer finds files faster than the Consumer can read them, the queue fills up.

In the benchmark session you’ll find I always put -j4 flag in ripgrep’s command, this is because I hard-coded the number of threads to 4 in cgrep. When writing a program I prefer to find another solution other than the dreaded “add more threads!” which is embarassingly parallel. I also prefer to have cohesion, the balance of the overall system is more important than having all cores (mine is 16) to run a program.

This is because in my normal daily workflow I have a fairly noisy system (Bloomberg non-stop, trading workstation to run my algo, 20+ tabs to do market research, and sometimes while having 4-5 Python instances to do data scraping). This is why I built cgrep to be more durable against these kinds of environment (noisy system) and you shall see from the benchmark the performance regression is not as magnified compared to ripgrep.

Engine Room: processing bulk data with SIMD

At start cgrep checks your system’s SIMD capabilities and automatically selects the best implementation (AVX512, AVX2, SSE). Using SIMD is like going from using straw to try extinguish a fire to using a proper firehose ~ instead of loading one character at a time, SIMD loads 64 at once.

I added an extra 64 bytes padding for SIMD safety, this also remove the necessity to bounds check constantly which is one of the causes of slow down.

// core of the AVX-512 search engine

// instead of checking one char at a time, we load 64 bytes into a register.

__attribute__((target("avx512f,avx512bw,avx512vl")))

static const u8* simd_search_avx512(const u8* haystack, size_t haystack_len, ...)

{

// ..setup..

const __m512i fc = _mm512_set1_epi8((char)needle[0]);

for (size_t i = 0; i < max; i += 64) {

__mmask64 m = _mm512_cmpeq_epi8_mask(_mm512_loadu_si512(haystack+i), fc);

while (m) {

// find the index of first match using hardware instruction (count trailing zeros)

const size_t pos = (size_t)__builtin_ctzll(m);

// verify full string match..

// clear the bit and keep searching this chunk

m &= m - 1;

}

}

return NULL;

}

Memory Strategy: think big, think in arenas and pages.

- Arena allocators: constantly asking the operating system for small blocks of memory (malloc) and releasing them (free) can be slow and lead to memory fragmentation.

cgrep uses Arenas. For temporary data, a thread asks for one giant block of memory (an “arena”) and then carves out the small pieces it needs from within that block. When it’s done, it can discard the entire arena at once. This is vastly faster and keeps memory tidy.

- Huge pages: no more 4KB pages, cgrep request in 2MB chunks! This is like having an index for a book that points to entire chapters instead of individual sentences. The CPU has far fewer entries to manage, TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) misses are drastically reduced, and memory access becomes much faster.

This will be explained more in the benchmark section where cgrep got much more cache references but has much less cache misses.

Memory Safety Net : safe_c.h comes into play!

With the use of my custom header file – memory leaks, buffer over/underflows, dangling pointers becomes irrelevant: smart pointers via AUTO_UNIQUE_PTR, bounds checking via StringView and Vector, RAII implementation for memory, files and mutexes, and many other discussed in the first article of this series.

Write high performance low level code without sacrificing safety.

// inside the worker thread that reads files:

static void* worker_literal_single(void* arg)

{

// ..context setup..

// AUTO_MEMORY == a smart pointer for raw memory.

// allocates the buffer and registers a cleanup function.

AUTO_MEMORY(buf, CHUNK_READ_SIZE + PADDING_SIZE);

if (!buf) return NULL;

while (true) {

// ..file reading logic..

const ssize_t bytes = read(ss->fd, buf, CHUNK_READ_SIZE);

if (bytes <= 0) {

// case study: early exit

// break the loop here because the file is done or an error occurred.

// in legacy C, you would likely forget to free(buf) here, causing a leak.

// with safe_c.h, we just break.

break;

}

// ..processing logic..

}

return NULL;

// 'buf' is automatically freed here when the function scope ends.

}

Regex Engine: PCRE2

cgrep uses PCRE2 JIT compiler with a specific design strategy to make it extra speedy: Avoidance. The thing is, the fastest way to run regex is to not run it at all (~ avoiding work for the regex engine). Let’s say I want to search for User ID: \d+ :

- cgrep analyzes the pattern and extracts a fast needle: the string “User ID: “. It knows that no match can possibly exist unless that specific literal string is present.

- Handshake: cgrep unleashes the SIMD engine to scan for “User ID: “ literal string while the regex engine sits idle, doing nothing (this is by design ~ avoiding unnecessary work).

- Only when the SIMD engine finds the needle, then it wake up the PCRE2 engine to verify if the digits

\d+actually follow.

This turns an O(N) complexity into a sub-linear search: if I’m scanning a 200MB log file and “User ID” only appears twice, the regex engine only runs twice too!

- Thread-local scratchpads: PCRE2 requires “match data” blocks to store information about where a match starts and ends. Allocating and freeing these blocks inside a loop would be catastrophic for performance!

Instead, cgrep allocates these scratchpads once per thread at startup. Each worker thread carries its own pcre2_match_data context. This allows the threads to run fully in parallel without fighting over memory locks or waiting for the operating system to allocate space for the results.

By combining the raw speed of native assembly (JIT) with the “Lazy” evaluation of fast needle skipping, cgrep ensures that the heavy cost of regex is paid only when necessary.

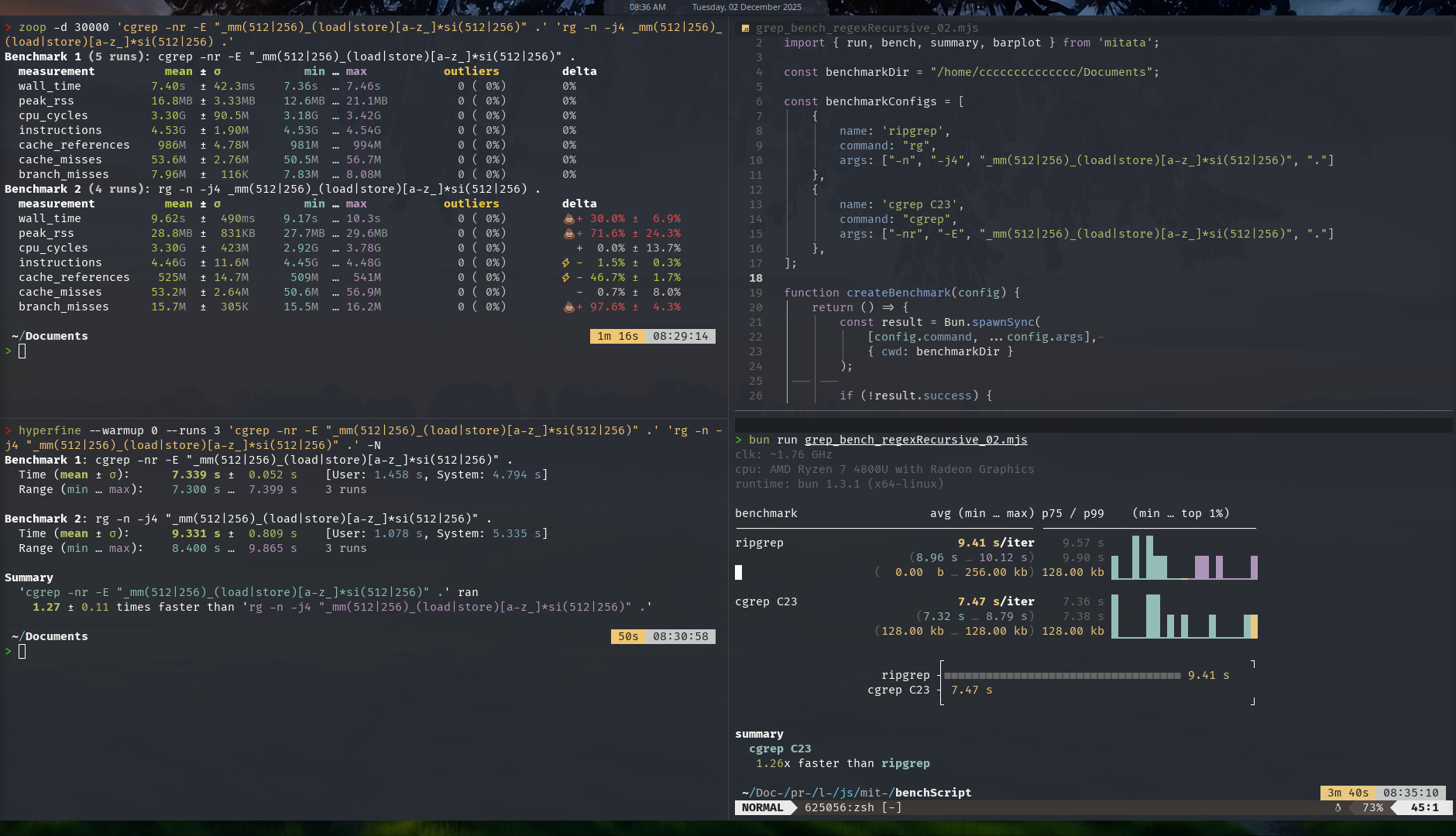

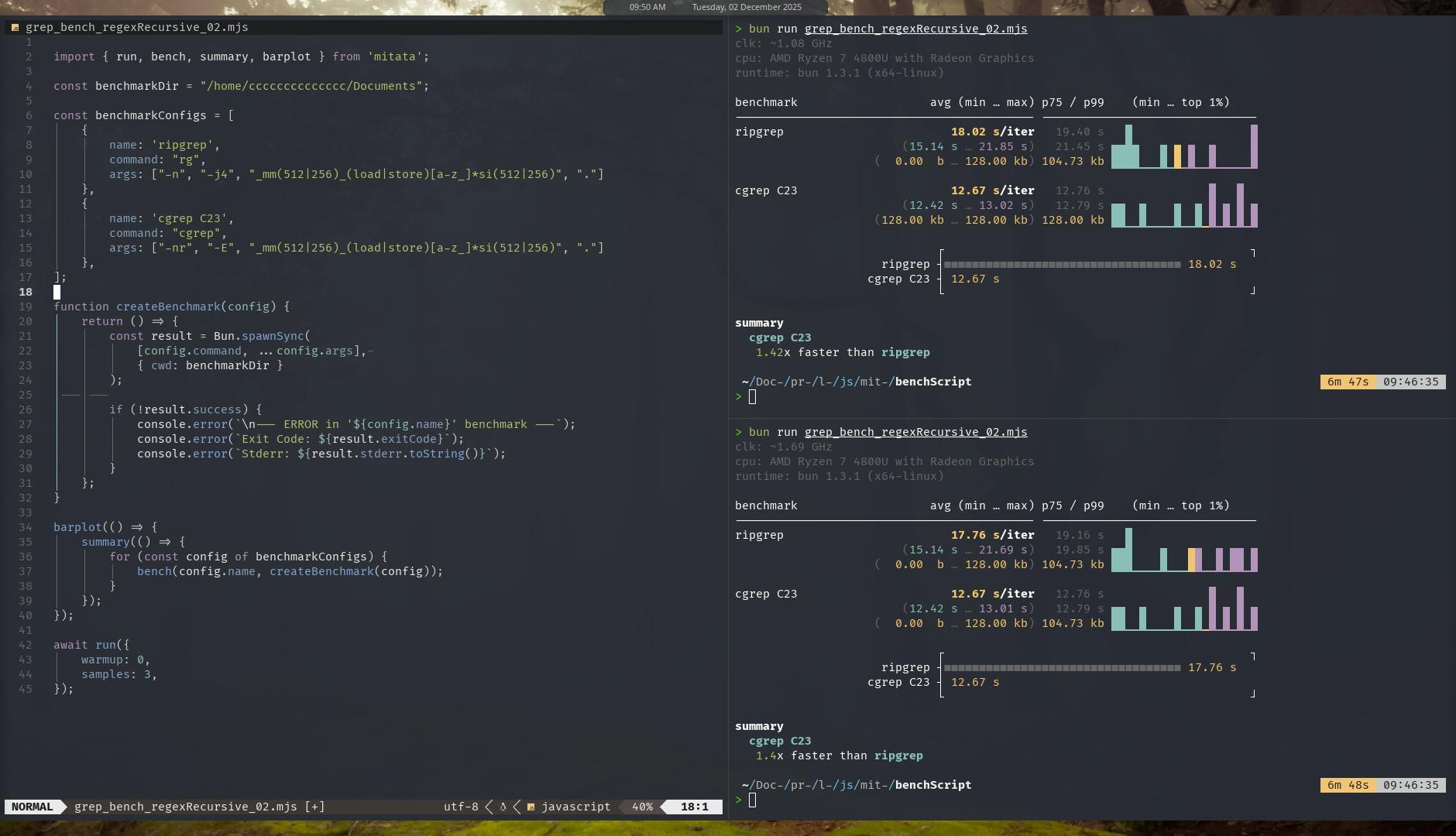

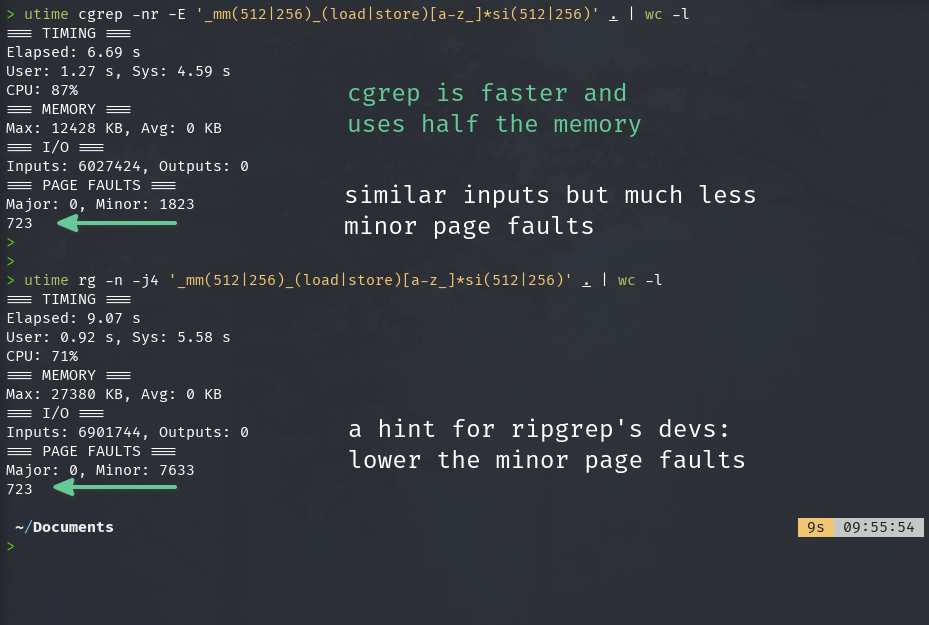

Benchmark - recursive directories

Okay let’s get to my favorite section: benchmarking! Lets start from the quiet test system:  In the quiet system, there’s minimum running processes, consider it as if it’s just rebooted with idle system usage. Result: cgrep is a bit faster compared to ripgrep (around 25% faster). Note the test was recursive grepping my entire Documents directory (and its sub dirs) which is quite massive with hundreds of sub dirs and thousands / tens of thousands files. I didn’t include the original GNU grep coz it took > 70 seconds to finish and each of these tests were repeated 20-30x, took too much time if I included GNU grep.

In the quiet system, there’s minimum running processes, consider it as if it’s just rebooted with idle system usage. Result: cgrep is a bit faster compared to ripgrep (around 25% faster). Note the test was recursive grepping my entire Documents directory (and its sub dirs) which is quite massive with hundreds of sub dirs and thousands / tens of thousands files. I didn’t include the original GNU grep coz it took > 70 seconds to finish and each of these tests were repeated 20-30x, took too much time if I included GNU grep.

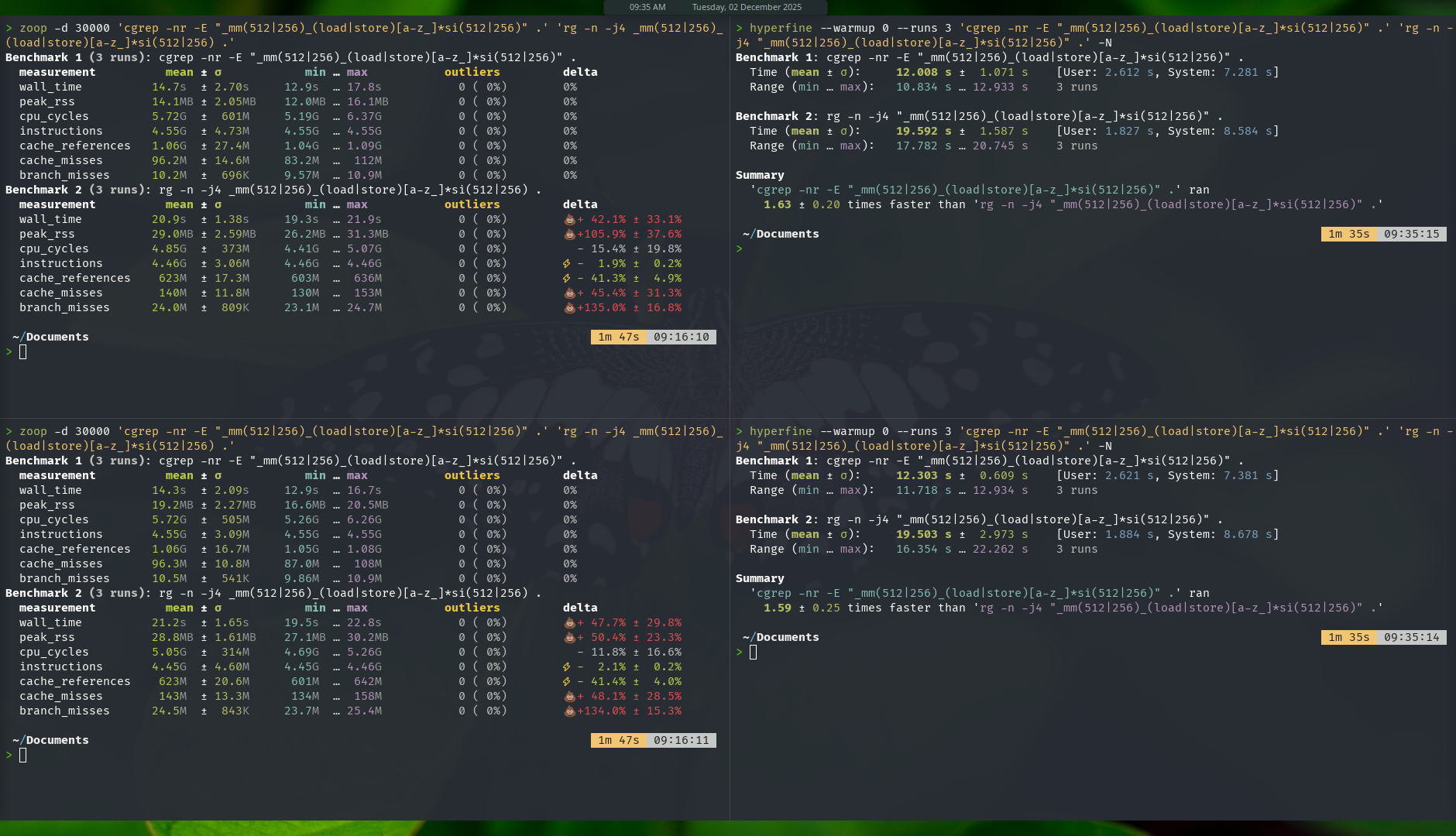

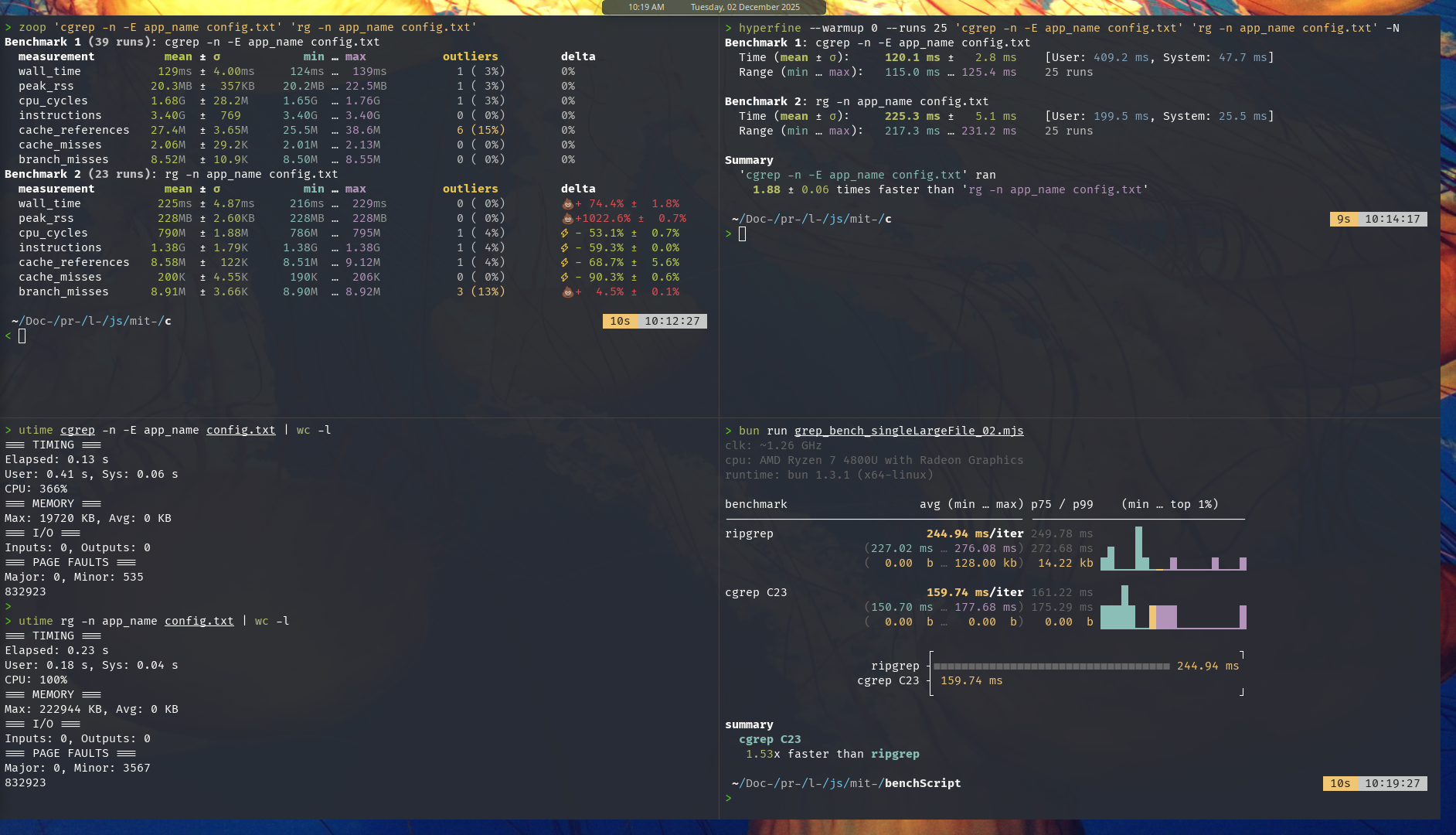

Below is the result for noisy test system

Zoop and Hyperfine

Mitata

Here’s how I did the test in the noisy system, :

- Running 2 instances of each zoop, hyperfine and mitata benchmark in parallel at the same time.

- Background processes: Trader Workstation app and a browser with 5 tabs open.

Result: the gap widen, cgrep is now 40-60% faster than ripgrep.

Now if you ask why bother differentiating between these quiet and noisy test environments? This goes back to the Levelized Cost of Resources article mentioned in the opening. The argument:

- When running an app, let’s say we want to grep something while we are in the middle of doing some work, do we close down all other running apps / processes before start grepping? Or do we just grep right away and let it run alongside other processes?

- Which one do you think simulates real world usage? Do you close down your apps when you want search for a keyword in your directories?

- These questions should capture my argument: controlled noisy system test is a better representation of real world usage.

I want to also encourage benchmark testers to start including noisy system test into their workflow, because this exercise captures a very important quality that is often forgotten: the durability of the program when facing non-ideal conditions. And from the bench it shows, cgrep has better durability, it does show performance regression as well, but not as bad as ripgrep’s regression.

Do you know the VW scandal back in 2008-2015? Volkswagen was caught manipulating its emmision test. Open air vs lab test showed open air got 35x more emission compared to the lab test (lab environment == the ideal condition). Turned out VW manipulated the software in the cars’ engines to recognize it’s on emission test mode, and then produced great bench output.

This is totally wrong and misleading practice! You can read about it here, here and here.

Note: each of these grep tests has been repeated 20-30x and while there were some slight variations on the results, aggregated outcome paints the same picture.

Additional info from utime stats, found matches are the consistent for the test command.

Benchmark - single large file

Ran on a 200MB config file with 10 million lines of data.  Note: by default ripgrep memory usage can be quite high on large files, but you can use the –no-mmap flag and it will use small memory footprint.

Note: by default ripgrep memory usage can be quite high on large files, but you can use the –no-mmap flag and it will use small memory footprint.

Conclusion

The biggest takeaway from this experimental project is that I’m going to keep using safe_c.h on all my C projects going forward coz it’s so damn good and convenient! It’s so good I think I’m going to reduce writing Zig programs (at least until Zig’s async i/o is released).

As for cgrep, I’m actually not surprised with it surpassing ripgrep in performance. If you had been following along and carefully read the articles mentioned at the start of this post, you’d see why I’m not at all surprised...the breadcrumbs were clear, akin to “it was written on the wall”.

Yeah for sure currently feature-wise cgrep only got like less than 30% of what’s available in the original grep and ripgrep, but these features are the ones I often use and as mentioned before: I built cgrep for my personal use.

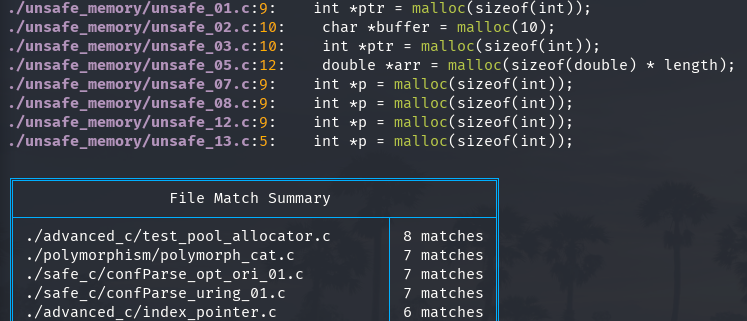

I’ve added a “Summary Table”, a feature I felt missing from grep and ripgrep:

What’s next?

So far I’m satisfied with cgrep in terms of feature and performance and I’ve already got several other projects on the pipeline:

- Smart Wallet: prototype done in safe_C23, Zig and Rust. I’m still contemplating what proglang should I select if I decide to go forward with this.

- Deterministic Financial Simulation (DFS): inspired by TigerBeetle’s Deterministic Simulation Testing, if TigerBeetle got fault injector, in DFS we got “Financial Events” injector. DFS turns the black-box nature of Markov Chain Monte Carlo into a glass-box ~ transparent, traceable, actionable.

If you enjoyed this post, click the little up arrow chevron on the bottom left of the page to help it rank in Bear’s Discovery feed and if you got any questions or anything, please use the comments section.