1.1. Origin of the Laplace Resonance

Ever since their serendipitous discovery by Galileo in 1610, the Jovian moons of Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto have been captivating targets for comparative planetology. A centerpiece of any discussion on the origin and evolution of the Jovian system is the resonant configuration between the former three moons, first quantified by Laplace in the late 18th century. The eponymous, three-body resonance consists of two 2:1 mean motion commensurabilities. Today, tidal heating in these moons is attributed to eccentricity forcing through this resonance, fueling Io’s extensive volcanism (e.g., S. J. Peale et al. 1979; A. S. McEwen et al. 2000), and preserving subsurface oceans in Europa and Ganymede…

1.1. Origin of the Laplace Resonance

Ever since their serendipitous discovery by Galileo in 1610, the Jovian moons of Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto have been captivating targets for comparative planetology. A centerpiece of any discussion on the origin and evolution of the Jovian system is the resonant configuration between the former three moons, first quantified by Laplace in the late 18th century. The eponymous, three-body resonance consists of two 2:1 mean motion commensurabilities. Today, tidal heating in these moons is attributed to eccentricity forcing through this resonance, fueling Io’s extensive volcanism (e.g., S. J. Peale et al. 1979; A. S. McEwen et al. 2000), and preserving subsurface oceans in Europa and Ganymede (e.g., P. Cassen et al. 1979; M. H. Carr et al. 1998; M. G. Kivelson et al. 2000, 2002).

The stability of the Laplace resonance can be expressed via librating resonant arguments (i.e., the conjunction longitude of each resonant pair, in a frame comoving with one of the two periapses). Henceforth denoting Io, Europa, and Ganymede as I, E, and G, the arguments are given by

where λ**X and ϖ**X are the mean longitude and longitude of periapsis of moon X, respectively. As such, I-E conjunctions occur at the periapsis of I but the apoapsis of E. While E-G conjunctions occur at the periapsis of E, G can be anywhere in its orbit (i.e.,* λE − 2λG + ϖG circulates; S. J. Peale 1999; S. J. Peale & M. H. Lee 2002). Combining the last two relations, we arrive at the Laplace relation: θ**L = λI − 3λE + 2λ*G ∼ π, describing the 4:2:1 resonance chain.

Models for the formation of the Laplace resonance fall into two major camps, invoking either (i) differential tidal expansion of orbits from tidal torques exerted by Jupiter (e.g., P. Goldreich & D. W. Sciama 1965; C. F. Yoder 1979; C. F. Yoder & S. J. Peale 1981; R. Greenberg 1987; R. Malhotra 1991; A. P. Showman & R. Malhotra 1997), or (ii) convergent, disk-driven migration in the Jovian circumplanetary disk (henceforth the “circum-Jovian” disk) within which the moons accreted (e.g., R. M. Canup & W. R. Ward 2002; S. J. Peale & M. H. Lee 2002; T. Sasaki et al. 2010; Y. Shibaike et al. 2019; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020; G. Madeira et al. 2021). Notably, these two paradigms differ vastly in their age estimates for the said resonance. While the former generally constrains this age to ≪3 Gyr (the exact value dependent on Jupiter’s tidal quality factor QJ), the latter implies an age coinciding with the lifetime of the circumsolar disk, which dissipated ∼4 Myr following the condensation of the solar system’s (SS) first solids (i.e., calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions; CAIs) ∼4.57 Gyr ago (H. Wang et al. 2017; B. P. Weiss et al. 2021; C. S. Borlina et al. 2022). In broad strokes, the tidal origin story posits that I and E were driven outward by the dissipative tide raised on Jupiter. By virtue of its larger mass, I approaches and eventually captures E into the 2:1 mean motion resonance. Moving out in lockstep, the pair subsequently encounters the 4:2:1 resonance with Ganymede. Resonant capture is thus envisioned to occur from “inside out,” with ensuing forced eccentricities damped by tidal dissipation in the moons, mainly I.

The disk-driven scenario envisions resonant capture from “outside in,” whereby the moons converge upon the 2:1 commensurabilities via so-called “Type I” migration (W. R. Ward 1997; H. Tanaka & W. R. Ward 2004; W. Kley & R. P. Nelson 2012; P. J. Armitage 2020). It has long been recognized that gravitational forces exerted by a planetary body on the disk material in which it is embedded lead to the launching of density waves at Lindblad resonances (i.e., mean motion resonances between the body and disk gas; P. Goldreich & S. Tremaine 1979, 1980). Such waves, along with co-orbiting gas executing horseshoe orbits (in the frame of the body), exert torques on the body that generally (i.e., for most of the disk, wherein density falls with radial distance from the host star/planet) lead to inward migration. Accordingly, I migrates inward until it encounters, and parks at, the disk inner edge (i.e., magnetospheric truncation radius; P. Ghosh & F. K. Lamb 1979; E. C. Ostriker & F. H. Shu 1995; F. S. Masset et al. 2006; S. Mohanty & F. H. Shu 2008). Subsequently, E and G migrate toward I and establish the Laplace resonance, with the timing of resonant captures dependent on their formation locations and disk structure.

A primordial origin by convergent migration is favored on several grounds. For one, the tidal scenario requires approximately in situ accretion of the moons. Considering the substantial presence of water ice in E, G, and Callisto (denoted C; O. L. Kuskov & V. A. Kronrod 2001; F. Sohl et al. 2002), this imposes an unrealistic constraint on models for the circum-Jovian disk: its midplane temperatures must be sufficiently low for the building blocks of the moons to lie beyond the water-ice sublimation front (henceforth denoted the “ice line”), despite their proximity to proto-Jupiter. Assuming (conservatively) an optically thin disk heated only by passive irradiation from proto-Jupiter (i.e., neglecting viscous heating, which is expected to dominate the inner disk region of interest; e.g., J. E. Chambers 2009; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020), with an effective temperature of TJ ∼ 1400 K, the ice line would have resided at a jovicentric distance  , where Tice ∼ 170 K represents the temperature of water-ice sublimation/condensation under nebular pressures (i.e., ≲10−3 bar), and RJ,pr Jupiter’s primordial radius, estimated to be ∼2–2.5 times its present-day radius RJ ≃ 7 × 107 m (K. Batygin & F. C. Adams 2025). This evaluates to ∼135–170RJ, well beyond the present-day location of C at ∼26RJ.

, where Tice ∼ 170 K represents the temperature of water-ice sublimation/condensation under nebular pressures (i.e., ≲10−3 bar), and RJ,pr Jupiter’s primordial radius, estimated to be ∼2–2.5 times its present-day radius RJ ≃ 7 × 107 m (K. Batygin & F. C. Adams 2025). This evaluates to ∼135–170RJ, well beyond the present-day location of C at ∼26RJ.

Moving on, recent measurements of the mass-dependent S and Cl isotopic composition in I’s atmosphere via the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) point to extensive volcanic activity and associated outgassing driven by tidal heating across most of the moon’s lifetime (K. de Kleer et al. 2024), thereby supporting a primordial Laplace resonance. Moreover, over the past decade, the discovery of numerous exoplanetary systems hosting planets in compact resonant chains (e.g., TRAPPIST-1; M. Gillon et al. 2017; R. Luger et al. 2017; G. Pichierri et al. 2024a, Kepler-223, S. Mills et al. 2016) suggests convergent migration into resonance is a common process in the evolution of planetary systems, and as such, renders the disk-driven scenario a natural and thus expected outcome. This is supported by the prevalent “peas-in-a-pod” architecture (i.e., intra-system uniformity in size and mutual spacing) exhibited by systems that define the Kepler survey (L. M. Weiss et al. 2018). This architecture naturally emerges from the “breaking” of resonant configurations established prior to disk dissipation (e.g., K. Batygin & F. C. Adams 2017; M. Goldberg & K. Batygin 2022), a point buttressed by the observation that resonance chains are ubiquitous in young (<100 Myr) systems and decay with age on a timescale on the order of ∼100 Myr (F. Dai et al. 2024).

1.2. Callisto’s Nonresonant Orbit

Any model for the creation of the Laplace resonance must address the exclusion of C from the resonant chain. In particular, disk-driven scenarios must contend with the relatively large mass of C (comparable to G), which should have led to rapid inward migration. The prevailing explanation for C’s nonresonant orbit is that it accreted late and/or slowly (i.e., ≫100 kyr), such that its migration was too slow to result in resonant capture with G prior to disk dissipation (S. J. Peale & M. H. Lee 2002; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020). This is indirectly supported by gravity measurements from the Galileo spacecraft, suggesting its interior is partially differentiated, characterized by a mixture of rock and ice extending from its center to beneath its outer ice shell (J. D. Anderson et al. 1998, 2001). That is, C formed too late for substantial interior heating by the short-lived radionuclide 26Al (t1/2 ∼ 0.717 Myr) to occur and/or too slowly (accretion timescale ≳0.5 Myr) for sufficient retention of accretionary energy, leading to an interior too cold for extensive melting of water ice (G. Schubert et al. 2004; A. C. Barr & R. M. Canup 2008).

In several works, C’s nonresonant orbit is described as a consequence of dynamical tides (J. Fuller et al. 2016), driving outward migration following the establishment of an 8:4:2:1 resonance chain (Y. Shibaike et al. 2019; G. Madeira et al. 2021). That is, C is originally locked in a 2:1 resonance with G, but breaks free therefrom after disk dissipation. While conceivable, these models have yet to be validated by astrometric observations of Callisto’s tidal migration timescale, and self-consistent simulations of Jupiter-satellite tidal dissipation effects remain absent.

Disk substructure offers an alternative explanation for C’s nonresonant orbit, as planet/satellite migration rates and directions depend strongly on local disk conditions, namely, the gradient in gas density (e.g., W. Kley & R. P. Nelson 2012). Over the past decade, ALMA observations have revealed the ubiquity of axisymmetric (e.g., concentric dust rings) and nonaxisymmetric (e.g., azimuthal dust trapping in vortices) substructures in protoplanetary disks (e.g., M. Flock et al. 2015; S. M. Andrews et al. 2018; C. P. Dullemond et al. 2018; see T. Birnstiel 2024 for review), showing them to be incompatible with long-adopted models for smooth, power-law disks. Pressure bumps serving as dust traps notably lend themselves to explaining population-level properties of disks (e.g., the size–luminosity relation; A. Tripathi et al. 2017) and exoplanetary systems (i.e., the intra-system uniformity in super-Earths; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2023). On the cosmochemistry front, nonuniformity in disk structure is supported by the salient dichotomy in nucleosynthetic isotope anomalies between non-carbonaceous and carbonaceous SS materials, calling for a prolonged (≳4 Myr) separation of dust reservoirs in the circumsolar disk (P. H. Warren 2011; C. Burkhardt et al. 2019; T. Kleine et al. 2020; T. E. Yap & F. L. Tissot 2023; F. L. Tissot et al. 2025). This separation is typically attributed to either Jupiter’s early formation (i.e., ∼20 Earth masses within 1 Myr from CAIs; T. S. Kruijer et al. 2017), a pressure bump near Jupiter’s formation region (R. Brasser & S. J. Mojzsis 2020), or preferential planetesimal formation at the silicate and water-ice sublimation fronts (J. N. Cuzzi & K. J. Zahnle 2004; K. A. Kretke & D. N. C. Lin 2007; F. Brauer et al. 2008; K. Ros & A. Johansen 2013; J. Drażkowska & Y. Alibert 2017; T. Lichtenberg et al. 2021; A. Morbidelli et al. 2022).

The prevalence of pressure bumps in protoplanetary disks provides confidence that they similarly occur in circumplanetary disks. Here, we show that such a bump in the circum-Jovian disk can serve as a migration “trap” for C, keeping it isolated from I, E, and G as they establish the Laplace resonance by convergent migration interior to the bump, thereby relaxing the need for its late/slow formation. The latter moons can form beyond the bump, as they are readily “pushed” across it once captured into a temporary mean motion resonance with their neighboring exterior moon (i.e., the combined Type I torque is sufficient to drive the interior moon over the bump). Accordingly, E pushes I across, G pushes E, and C pushes G. While we remain agnostic to the underlying origin for the bump invoked, we note that the ice line serves as a natural place for its development (e.g., K. A. Kretke & D. N. C. Lin 2007; F. Brauer et al. 2008; B. Bitsch et al. 2015; S. Charnoz et al. 2021; J. Müller et al. 2021).

The paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we provide an overview of the circum-Jovian disk model adopted, as well as the disk-dependent parametrizations for Type I migration and eccentricity damping. Derivations of key equations introduced in this section are relegated to the Appendix. A description of our simulations and their setup (e.g., initial conditions) is given in Section 3. In Section 4, we present our results, including a thorough analysis of a fiducial case and an exploration of how the structure of the pressure bump (i.e., its height and width) impacts the emergent architecture of the system. We discuss possible origins for pressure bumps, as well as the impact on our results from relaxing simplifying assumptions in our disk model in Section 5. There, we also consider variations on our envisioned scenario for the assembly of the Laplace resonance, and discuss our work in the context of Callisto’s interior structure. Final remarks are given in Section 6.

2.1. The Circum-Jovian Decretion Disk

Over the past decade, both hydrodynamical simulations (T. Tanigawa et al. 2012; A. Morbidelli et al. 2014; J. Szulágyi et al. 2022) and direct observations (R. Teague et al. 2018, 2019) of gas flow in the vicinity of gap-carving giant planets have inspired a dramatic reimagination of circumplanetary disk formation and evolution. Unlike the circumstellar disks in which they are hosted, circumplanetary disks are not mainly (i.e., across most of their radial extents) thought to be accreting, but decreting. Indeed, the said studies suggest that gas and dust in such disks are vertically delivered onto the giant planet Hill sphere from approximately a hydrostatic scale height above the circumstellar disk midplane via meridional flows, resulting in decretion beyond the centrifugal radius (see Figure 1). Following the approach of K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli (2020), we adopt a steady-state viscous model for the circum-Jovian decretion disk. This model departs from the classic accretion scenario of R. M. Canup & W. R. Ward (2002), but retains the key feature of being “gas starved.” That is, gas is introduced into, and cycled out of, the disk throughout its lifetime, gradually providing the dust that will constitute the moons.

Figure 1. Schematic of the circum-Jovian decretion disk. Gas and dust from the circumsolar accretion disk are subsumed into the Jovian disk from approximately one hydrostatic scale height via meridional flows and move outward beyond the magnetospheric truncation radius. Decretion  is driven by turbulence manifesting as a macroscopic viscosity, and parametrized by the Shakura–Sunyaev α parameter. The four Galilean moons are envisioned to form beyond the ice line and pressure bump, and undergo Type I migration inward. The bump serves as a migration trap, preventing Callisto from convergent migration into resonance with Io, Europa, and Ganymede.

is driven by turbulence manifesting as a macroscopic viscosity, and parametrized by the Shakura–Sunyaev α parameter. The four Galilean moons are envisioned to form beyond the ice line and pressure bump, and undergo Type I migration inward. The bump serves as a migration trap, preventing Callisto from convergent migration into resonance with Io, Europa, and Ganymede.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

The disk surface density profile Σ(r) (r being the radial jovicentric distance) serves as the backdrop to our simulations, to which the positions of the Galilean moons at each time step are mapped for the calculation of their respective Type I migration (i.e., semimajor axis damping) and eccentricity damping rates (i.e.,  and

and  ). Here, we outline the construction of Σ(r), showing how a pressure (i.e., Σ) bump in the disk follows directly from the implementation of a Gaussian dip in an otherwise flat profile of the Shakura–Sunyaev α parameter for turbulent viscosity (N. I. Shakura & R. A. Sunyaev 1973). A detailed derivation of our disk model is provided in the Appendix.

). Here, we outline the construction of Σ(r), showing how a pressure (i.e., Σ) bump in the disk follows directly from the implementation of a Gaussian dip in an otherwise flat profile of the Shakura–Sunyaev α parameter for turbulent viscosity (N. I. Shakura & R. A. Sunyaev 1973). A detailed derivation of our disk model is provided in the Appendix.

By conservation of mass and angular momentum, Σ(r) takes the form (D. Lynden-Bell & J. E. Pringle 1974)

where  is the mass decretion rate, and ν the turbulent viscosity facilitating decretion. The former is taken to be ∼0.1 MJ Myr−1, with M**J ≃ 1.9 × 1027 kg being Jupiter’s present-day mass. The latter is given by

is the mass decretion rate, and ν the turbulent viscosity facilitating decretion. The former is taken to be ∼0.1 MJ Myr−1, with M**J ≃ 1.9 × 1027 kg being Jupiter’s present-day mass. The latter is given by

where we have substituted for the isothermal sound speed  and the hydrostatic scale height of the disk h ≃ c**s/Ωk (assuming it is vertically isothermal at all r) in the second equality. Here, kB is the Boltzmann constant (≃1.38 × 10−23 J K−1), μ the mean molecular mass of disk gas (≃2.4 proton masses), T the disk midplane temperature, and

and the hydrostatic scale height of the disk h ≃ c**s/Ωk (assuming it is vertically isothermal at all r) in the second equality. Here, kB is the Boltzmann constant (≃1.38 × 10−23 J K−1), μ the mean molecular mass of disk gas (≃2.4 proton masses), T the disk midplane temperature, and  the Keplerian angular velocity, G ≃ 1.67 × 10−11 m3 kg−1 s2 being the gravitational constant. Returning to Equation (2), RHill represents Jupiter’s Hill radius, which roughly defines the disk’s outer edge. It is given by

the Keplerian angular velocity, G ≃ 1.67 × 10−11 m3 kg−1 s2 being the gravitational constant. Returning to Equation (2), RHill represents Jupiter’s Hill radius, which roughly defines the disk’s outer edge. It is given by  , where aJ ≃ 5.2 au and M⊙ ≃ 2 × 1030 kg are Jupiter’s semimajor axis and the solar mass, respectively. Toward (proto-)Jupiter, the disk is truncated at the magnetospheric cavity R**T, which we take to be ∼5 RJ. Note that in a viscous decretion disk, the quantity

, where aJ ≃ 5.2 au and M⊙ ≃ 2 × 1030 kg are Jupiter’s semimajor axis and the solar mass, respectively. Toward (proto-)Jupiter, the disk is truncated at the magnetospheric cavity R**T, which we take to be ∼5 RJ. Note that in a viscous decretion disk, the quantity  must decay with r, since the radial velocity of gas v**r is directed toward

must decay with r, since the radial velocity of gas v**r is directed toward  .

.

As is evident, Σ(r) depends on the specification of T(r). Here, we assume an optically thin disk heated solely by viscous shear, for which we have

where σSB ≃ 5.67 × 10−8 W m−2 K4 is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. Notably, with this prescription, the disk aspect ratio h/r ( ; on which the characteristic Type I damping timescale depends strongly (see Section 2.3), is independent of α.

; on which the characteristic Type I damping timescale depends strongly (see Section 2.3), is independent of α.

An optically thin disk is physically motivated by consideration of the mechanism with which it sources its gas and dust. As noted above, the vertical influx into the circum-Jovian disk (assumed to be confined within R**T) is sourced from approximately one scale height above the circumsolar disk midplane, denoted H to avoid confusion with h. It is well established that, owing to a balance between turbulent diffusion and gravitational settling, dust particles of a given size settle toward the midplane and establish a sub-disk of scale height H**d < H (B. Dubrulle et al. 1995). In accord with intuition, the largest particles (i.e., centimeter scale and above) in the dust size distribution settle most readily, and are characterized by the lowest H**d. Only the smallest (i.e., micron- to 1 mm-scale) particles, constituting a meager fraction of the solid budget, are dispersed to the upper disk layers (i.e., H**d ∼ H). Thus, gas subsumed into the circum-Jovian disk is expected to be dust-poor (T. Tanigawa et al. 2012; Y. Shibaike et al. 2019; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020), characterized by a metallicity (i.e., dust-to-gas ratio) far smaller than that of the circumsolar disk  .

.

For clarity, consider two gas parcels, one at the circumsolar disk midplane, and the other at height H above it. The former contains  dust by mass, of which ∼1% may be held in micron-scale particles to which most of the disk opacity is attributed. This parcel possesses a “micron-scale” metallicity

dust by mass, of which ∼1% may be held in micron-scale particles to which most of the disk opacity is attributed. This parcel possesses a “micron-scale” metallicity  . The latter parcel is also characterized by

. The latter parcel is also characterized by  , since the density of both gas and micron-scale dust is reduced by

, since the density of both gas and micron-scale dust is reduced by  (H**d ∼ H). However, here

(H**d ∼ H). However, here  , as settling of particles for which H**d < H has largely stripped the parcel of solids.

, as settling of particles for which H**d < H has largely stripped the parcel of solids.

Within the circum-Jovian disk, dust coagulation may further diminish  (I. Mosqueira & P. R. Estrada 2003; C. P. Dullemond & C. Dominik 2005; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020). If sufficiently rapid, dust accumulation would occur at and near the centrifugal radius (i.e., the infall point), such that only a small fraction of micron-scale particles are advected outward (S. H. Lubow & R. G. Martin 2013). Moreover, our model is envisioned to operate in the late stages of the circum-Jovian disk, when the moons have accreted enough mass to undergo Type I migration. At this stage, infall (and thus the decretion rate

(I. Mosqueira & P. R. Estrada 2003; C. P. Dullemond & C. Dominik 2005; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020). If sufficiently rapid, dust accumulation would occur at and near the centrifugal radius (i.e., the infall point), such that only a small fraction of micron-scale particles are advected outward (S. H. Lubow & R. G. Martin 2013). Moreover, our model is envisioned to operate in the late stages of the circum-Jovian disk, when the moons have accreted enough mass to undergo Type I migration. At this stage, infall (and thus the decretion rate  ) may have waned substantially from dissipation of the circumsolar disk, such that the circum-Jovian disk, and more specifically its optical depth τ, is low.

) may have waned substantially from dissipation of the circumsolar disk, such that the circum-Jovian disk, and more specifically its optical depth τ, is low.

Adopting an optically thick disk introduces a factor of ∼(3τ/4)1/4 to T(r) in Equation (4) (P. J. Armitage 2020), where  (B. Bitsch et al. 2014) and the dust opacity k**d ∼ 30 m2 kg−1. With

(B. Bitsch et al. 2014) and the dust opacity k**d ∼ 30 m2 kg−1. With  , it is clear that for Σ ∼ a few times 104 kg m−2 (applicable to the vicinity of the ice line in our model), we have τ ∼ 5. Thus, neglecting the impact of opacity amounts to underestimating T by merely factor of order unity. While we proceed with the optically thin assumption, we recognize the uncertainties that permit it, and discuss the significant changes its relaxation can have on the details of our work in Section 5.2. At this stage, note that while τ appears to be a weak control on our disk model and thus simulation results (entering as it does into the expression for T(r) to the 1/4 power), the Type I eccentricity damping timescale (see Section 2.3 below) on which the stability of the system strongly depends scales as ∼T2. Thus, an increase in a factor of a few in T (due to say

, it is clear that for Σ ∼ a few times 104 kg m−2 (applicable to the vicinity of the ice line in our model), we have τ ∼ 5. Thus, neglecting the impact of opacity amounts to underestimating T by merely factor of order unity. While we proceed with the optically thin assumption, we recognize the uncertainties that permit it, and discuss the significant changes its relaxation can have on the details of our work in Section 5.2. At this stage, note that while τ appears to be a weak control on our disk model and thus simulation results (entering as it does into the expression for T(r) to the 1/4 power), the Type I eccentricity damping timescale (see Section 2.3 below) on which the stability of the system strongly depends scales as ∼T2. Thus, an increase in a factor of a few in T (due to say  being closer to 10−3 than 10−4) leads to a commensurate decrease in the efficiency of eccentricity damping.

being closer to 10−3 than 10−4) leads to a commensurate decrease in the efficiency of eccentricity damping.

2.2. Implementing a Pressure Bump

A steady-state disk, as described above, is one wherein  is invariant with r (i.e., expressing negligible buildup/loss of mass in any disk annulus). As such, the functional form of Σ(r), beyond a decay with r facilitated by Ωk, is set wholly by that of α(r). More specifically, any local decrease in α must be counteracted with an increase in Σ, so as to maintain a constant

is invariant with r (i.e., expressing negligible buildup/loss of mass in any disk annulus). As such, the functional form of Σ(r), beyond a decay with r facilitated by Ωk, is set wholly by that of α(r). More specifically, any local decrease in α must be counteracted with an increase in Σ, so as to maintain a constant  across the disk. Since the disk midplane pressure

across the disk. Since the disk midplane pressure  , where the gas density

, where the gas density  , a bump in P is equivalent to one in Σ, and can be implemented as a dip in α.

, a bump in P is equivalent to one in Σ, and can be implemented as a dip in α.

In our model, the dip in α(r) takes the form of an inverted Gaussian centered on r0, the radial location of the P bump. Its minimum is denoted α0, and moving away from r0, α rises and plateaus at a constant value α**c ∼ 10−3. With these specifications, α(r) is given by

where

The width of the Gaussian w reflects that of the P bump, and must be ≳h0 (the hydrostatic scale height at r0) for the bump to be stable against Rossby wave instabilities (H. F. J. M. Li et al. 2000; C. P. Dullemond et al. 2018), and thus a long-lived disk feature. The structure of the Σ/P bump controls its ability to halt the Type I migration of a moon close to its peak, and is set by both w/h0, and ratio α**c/α0 (specifying its “height”), henceforth denoted as

We treat R**α and w/h0 as free parameters, with fiducial values of 2.5 and 1.25 (see Section 4.1), and 2 and 1 (see Section 4.3), respectively. In exploring their impact on the dynamical evolution of the Galilean moons (see Section 4.2), the former is allowed to range from 1.5 to 5, and the latter from 1 to 2.5.

Given a specification of R**α and w/h0, an aspect ratio for the bump can be calculated. To do so requires a translation of R**α to a length scale representative of bump height. The scale height h0 alone is inadequate—as mentioned above, the assumption of an optically thin disk renders h oblivious to changes in α, and thus the P bump. To proceed, note that while the height at which the midplane P falls by ≃e−1/2 does not change with α, P itself does. Stated differently, while h0 is constant with R**α, P(z = h0) is not. The bump simply shifts all P contours away from the midplane. That said, we define the height of the bump Δh as the difference between h0 and the height corresponding to P(z = h0) in the absence of the bump, which lies slightly above h0. The expression for Δh is (see the Appendix)

Accordingly, the aspect ratio is defined as Δh/w.

2.3. Type I Damping

Comprehensive investigations of planet–disk interactions require resource-intensive hydrodynamic simulations (e.g., P. Cresswell & R. P. Nelson 2008; B. Bitsch & W. Kley 2010; G. Pichierri et al. 2023; 2024b). When the focus of study lies not in the detailed nature of such interactions, but instead their phenomenology (e.g., how they sculpt the architecture of a planetary system), as is the case here, a more viable avenue is to rely on N-body simulations wherein fictitious forces mimicking the dynamical impact of disk material are implemented. Having constructed the steady-state surface density profile Σ(r), we now turn to the Type I forces it underpins—recall that satellite migration and e-damping are driven by torques exerted on the satellite by the local, perturbed gas. In our simulations, these forces are introduced as operators through REBOUNDx (see Section 3; D. Tamayo et al. 2020). Here, we outline the key equations used to compute  and

and  for each moon.

for each moon.

The evolution of a and e under the action of Type I forces can be expressed in terms of their respective timescales (i.e.,* τa* and *τe*) as

In terms of the evolution timescale  , where

, where  is the angular momentum, τ**a takes the form

is the angular momentum, τ**a takes the form

(This relationship is derived in the Appendix.) Formulae for τ**m and τ**e are expressed in terms of the the characteristic Type I damping timescale τwave, given by (H. Tanaka et al. 2002; H. Tanaka & W. R. Ward 2004)

Here, m**X and a**X represent the mass and semimajor axis of moon X (I, E, G, or C). Notably, τwave is shorter for larger m**X and Σ, with consequences for resonant capture (see Section 4). The timescale τ**m is given by

where γ is the local power-law index of Σ(r) ∼ r−γ (i.e., its slope in log-log space evaluated at the instantaneous position of the body considered). Note that γ controls the direction of migration (i.e., the sign of τ**m), and underlies the function of the pressure bump as a “trap” (on the interior side of the bump, γ is negative, leading to outward migration). Physically, this reflects the enhancement of the positive corotation torque, which (down-slope of the bump) overcomes the negative Lindblad torque (see Section 5.2.2). The quantity P**e is obtained from fitting 3D hydrodynamic simulations of protoplanet disk-driven migration (P. Cresswell & R. P. Nelson 2008), and takes the form

where e**X is the eccentricity of moon X. All r-dependent disk parameters (i.e., Σ, Ωk, h) are, like γ, evaluated at the instantaneous position of the body. Like τ**m, the expression for τ**e is also refined by best fits to the said hydrodynamic simulations, yielding

With these prescriptions,  and

and  are computed at each time step dt (see Section 3), and the variations

are computed at each time step dt (see Section 3), and the variations  and

and  are superposed with those resulting from gravitational interactions (e.g., resonant “pumping” of eccentricities).

are superposed with those resulting from gravitational interactions (e.g., resonant “pumping” of eccentricities).

Our N-body simulations are performed using the WHFAST symplectic Wisdom–Holman integrator in the REBOUND package (H. Rein & S. F. Liu 2012; H. Rein & D. Tamayo 2015), with a time step dt set to 5% the orbital period of I, the innermost moon. Here, we describe their relevant parameters, namely, the initial conditions of each moon, the position of the pressure bump, and the distance from (proto-)Jupiter at which we halt migration. The latter, denoted Rstop, is implemented simply by asserting that the direction of I’s migration past that point is reversed (i.e., flipping the sign of τ**m, and thus  , as calculated with Equations (9) and (10) above).

, as calculated with Equations (9) and (10) above).

We first performed simulations in which Rstop was set to 0.03 RHill, a factor of ≃4.5 larger than Rtrunc ≃ 0.0067 RHill, where migration is expected to have ceased in reality. This choice for Rstop is not physically motivated, but serves to reduce runtime, as these illustrative simulations make up the R**α–w space (see Section 2.2) exploration in Section 4.2. The only constraint on Rstop is that it needs to be sufficiently far within the pressure bump such that resonant capture thereat (i.e., the establishment of the Laplace resonance) does not interfere with dynamics at the bump. Here, we positioned the pressure bump (r0) at 0.18 RHill, far beyond the ice line to which it may owe its origin. The bump need not be associated with the ice line, however, and could have emerged at any “dead zone” where turbulence is reduced (see Section 5.1). The total duration of each simulation is 100 kyr, and the time at which each moon is initialized t**X is as follows: tI = tE = 0, tG = 25 kyr, and tC = 45 kyr. The initial semimajor axes of each moon a**i,X is defined relative to r0, and given by a**i,I/r0 = 1.1, a**i,E/r0 = 2, and a**i,G/r0 = a**i,C/r0 = 3. As capture into first-order mean motion resonances does not depend on inclination i (i.e., it is absent in the linear expansion of the disturbing function; e.g., K. Batygin 2015), the moons are initiated with i = 0, and the system remains planar across the simulation. With eccentricities e**X set to 0 at t**X, all other orbital parameters (i.e.,* ϖX*) are left undefined. The fiducial case discussed in Section 4.1 is characterized by *Rα* = 2.5 and w = 1.25h0.

Following the simulations just described, we performed one other with Rstop = Rtrunc and r0 just beyond (i.e., a factor of 1.25) the ice line (see Section 4.3). This simulation, more representative of how we envision the formation of the Laplace resonance, involves a pressure bump with R**α = 2 and w = h0. As discussed further below, given the smaller r0 (and thus the overall higher Σ at the bump), the bump must be smaller to accommodate a stable replacement of E by G at its peak. In other words, having captured E in resonance and proceeding to shepherd it across the bump via migration in lockstep, the torque (dependent on Σ; see Equation (11)) on G must not be so large as to destabilize the resonance. The total duration of this simulation is 60 kyr, and the moons are initialized at tI = tE = 0, tG = 15 kyr, and tC = 25 kyr. Respective a**i,X/r0 remain the same, and as in the “reduced runtime” simulations above, e**X and i**X were set to 0 at t**X.

The satellite introduction times tE,G,C, in addition to disk structure, control the timescale on which our proposed scenario unfolds. Importantly, this timescale, ultimately set by tC, cannot exceed the expected lifetime of the circum-Jovian disk. Broad bounds on the start and end of the disk can be gleaned from cosmochemistry. Regarding the latter, paleomagnetic investigation of meteorites suggests the circumsolar disk, the feedstock for Jupiter’s runway gas accretion, and the circum-Jovian disk dissipated at ∼4 Myr from CAI formation (H. Wang et al. 2017; C. S. Borlina et al. 2022). Regarding the former, analyses of nucleosynthetic isotope anomalies in SS materials spanning a wide range (i.e., a few Myr) of inferred accretion ages indicate an early (i.e., within ∼1 Myr post-CAIs) separation of inner and outer SS solid reservoirs, widely thought to have been facilitated by Jupiter’s formation (T. S. Kruijer et al. 2017; T. Kleine et al. 2020; T. E. Yap & F. L. Tissot 2023; F. L. Tissot et al. 2025). Thus, a circum-Jovian disk lifetime on the order of ∼1 Myr is not implausible. As shown below, our choice of tC in the tens of kiloyears leads to the establishment of the Laplace resonance within ∼0.1 Myr, concordant with the said cosmochemical constraints.

4.1. A Fiducial Case

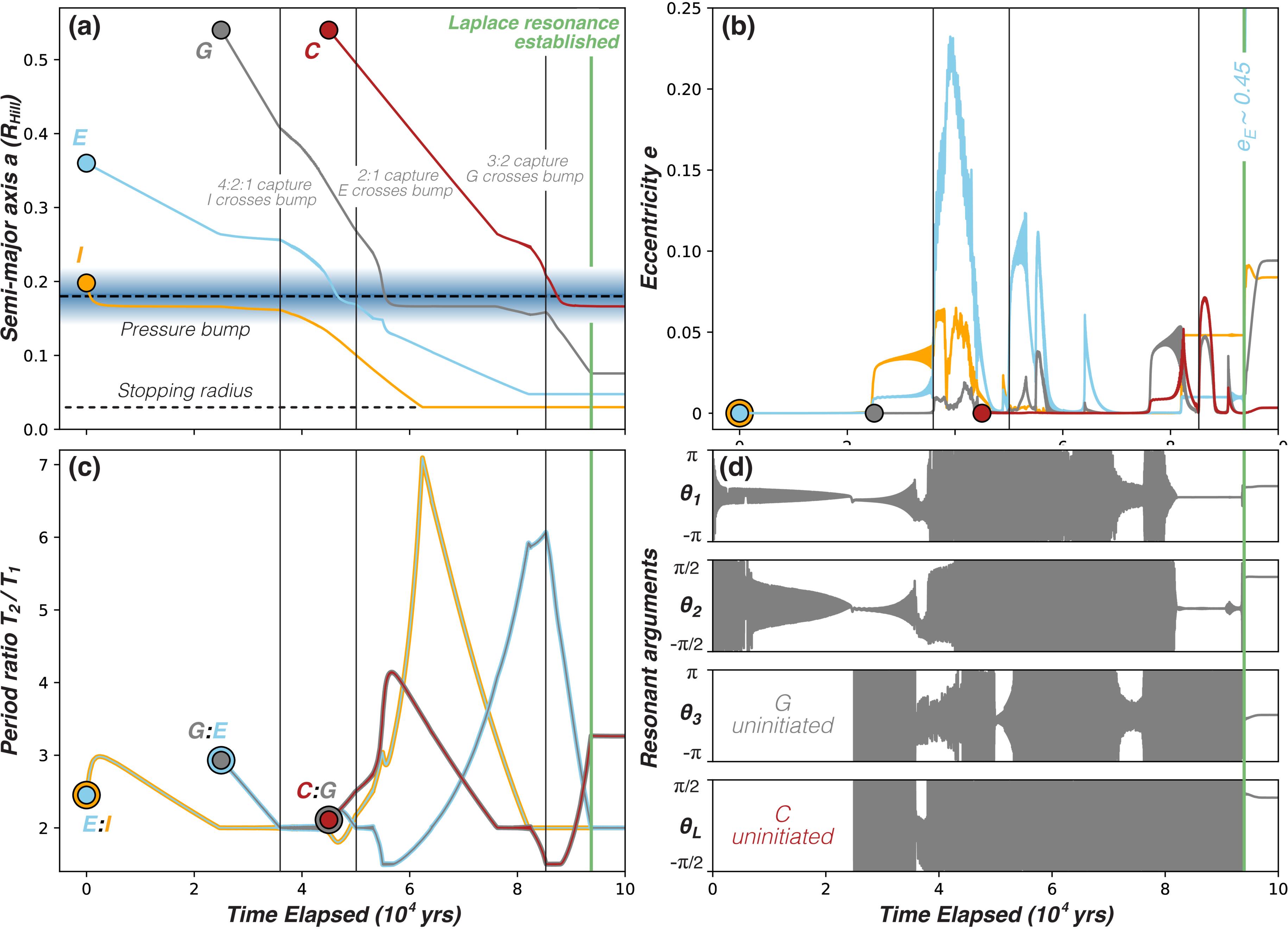

Before exploring how the structure of the pressure bump determines the final architecture of the Jovian system (see Section 4.2), it is worthwhile to consider in detail a fiducial case for which (i) the 4:2:1 Laplace resonance is established, and (ii) C is trapped at the bump. That is, an example of a R**α and w pair leading to the desired outcome (for the given r0 and disk model). In Figure 2, we provide the results from such a case, with R**α = 2.5 and w = 1.25h0. The four panels depict the (a) semimajor axes and (b) eccentricities of the moons, their (c) outer-inner period ratios, and (d) the resonant arguments θ1−3,L (see Section 1) across the simulation.

Figure 2. Simulation results for Rstop = 0.03RHill > R**T = 5RJ and r0 = 0.18RHill, assuming fiducial Rα = 2.5 and w = 1.25h0. Panels indicate the (a) semimajor axes and (b) eccentricities of the moons, (c) their outer-inner period ratios, and (d) resonant arguments between Io, Europa, and Ganymede. Key resonant captures are denoted by vertical lines. See Section 4.1 for a discussion.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

Soon after the start of the simulation, I is trapped at the pressure bump. At ∼25 kyr (when G is introduced), E captures I in a 2:1 resonance, “pushing” it across the bump in lockstep, albeit weakly given its small mass (see Section 2.3). At ∼35 kyr, G captures E into a 2:1 resonance, increasing the total torque on the three-body resonant chain and rapidly moving I past the bump. The steep, and thus rapid, climb of E up the bump at ∼45 kyr (when C is introduced) breaks the resonant chain, and leaves E trapped at its peak while I proceeds to migrate inward toward Rstop. In ∼5 kyr, G recaptures E into a 2:1 resonance and pushes it across the bump, leaving itself trapped. At ∼75 kyr, C captures G into a 2:1 resonance. As G is ushered down the bump, the torque driving it outward (i.e., back toward the peak) increases (due to the steepening profile) and eventually breaks the resonance. At approximately the same time, E enters the 2:1 resonance with I at Rstop. At ∼85 kyr, C recaptures G into the (stronger) 3:2 resonance and successfully displaces G short of ∼90 kyr. Finally, while C remains at the bump, G enters the 2:1 resonance with E, establishing the 4:2:1 Laplace resonance before 100 kyr.

With each resonant capture described above, eccentricities are pumped and stabilized by Type I e-damping. At the formation of the Laplace resonance, eI ∼ 0.08, eE ∼ 0.45, and eG ∼ 0.09. These eccentricities are sufficiently high as to induce asymmetric librations of resonant arguments away from 0 and π (S. J. Peale & M. H. Lee 2002; K. Batygin & A. Morbidelli 2020), as observed in Figure 2(d). Following disk dissipation, tidal dissipation assumes the role of e-damping, and without Type I migration “forcing” the moons into deeper resonance, eccentricities are rapidly damped (to ≪0.01). This leads to the Laplace resonance observed today.

4.2. Impact of Bump Structure

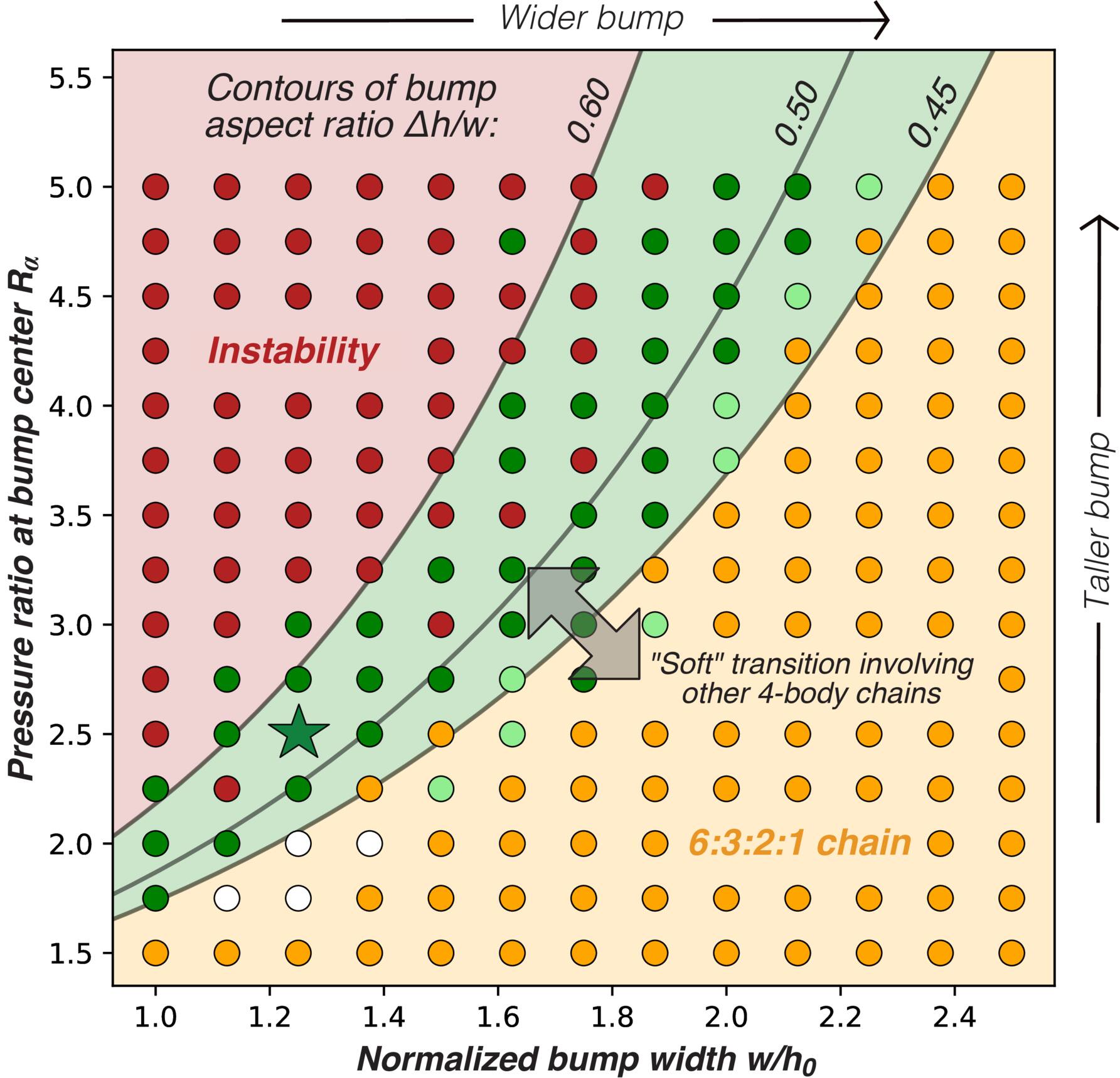

We have demonstrated, for a fiducial pressure bump “height” R**α and width w, that I, E, and G can be sequentially trapped at the bump, and stably “pushed” across it via resonant capture and subsequent lockstep migration. Having displaced G from the bump, C remains trapped while the Laplace resonance is established. We now explore how variations in R**α and w modify the simulation outcome. In doing so, we map out three main regimes in parameter space, and show that they can be understood as reflecting a single governing parameter—the bump aspect ratio Δh (see Section 2.2 and Equation (8)).

Allowing R**α to range between 1.5 and 5 in increments of 0.25, and w/h0 between 1 and 2.5 in increments of 0.125, a total of 195 simulations were performed (including the fiducial case from Section 4.1; Figure 2). The final results of these simulations are summarized in Figure 3. The said regimes are easily discerned and can be intuitively understood. As the bump gets wider and/or shorter (i.e., as we move to the bottom right of parameter space), it loses its function as a migration trap. Accordingly, all four moons make it past the bump, establishing a 6:3:2:1 resonant chain (see Figure A1 for example with R**α = 2.5 and w = 2h0). The 3:2 resonance between E and G reflects the large mass and thus rapid migration of the latter, violating the adiabatic criterion for 2:1 resonant capture (i.e., “overshooting” it; K. Batygin 2015). Conversely, as the bump gets thinner and/or taller (i.e., as we move to the top left of parameter space), it becomes too effective, or “stiff,” as a trap, such that the moons cannot be “pushed” across. Here, the moons pile up in a resonant chain at the bump, and Type I migration pumps eccentricities until instability sets in, resulting in either (i) a collision (see Figure A2 for example with R**α = 4.5 and w = 1.25h0), (ii) ejection from the system, or (iii) orbital exchanges (between E and G; P. Cresswell & R. P. Nelson 2008). In between the two regimes just described lies a “Goldilocks” zone, wherein the bump is “semipermeable” and thus conducive to both trapping and migration across it following resonant capture. The general sequence of events in these simulations is consistent with that described in Section 4.1.

Figure 3. Final simulation outcomes from exploration of R**α–w parameter space. Three main regimes are discerned: (red) for thin and tall disks to the top left, the bump is too “stiff” a trap, ultimately leading to a dynamical instability; (orange) for short and wide disks to the bottom right, the bump fails to trap the moons, leading to the formation of a 6:3:2:1 resonant chain; (green) between (red) and (orange) lies a “Goldilocks” zone wherein the bump can both function as a trap, and allow the moons to be “pushed” across it by migration in lockstep following resonant capture. This zone corresponds roughly to bump aspect ratios Δh between 0.45 and 0.6. Along its former boundary are simulations wherein alternatives to the resonant chain in (orange) are realized (light green: 8:4:2:1; and white: e.g., 12:6:3:2). The green star corresponds to the fiducial case discussed in Section 4.1. See Section 4.2 for a discussion.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

Overlaid on Figure 3 are contours of Δh/w. As is evident, these contours nicely bound the trend of the “Goldilocks” zone, demarcating boundaries between the three regimes discussed and indicating that (for our choice of r0, see Section 3) the desired outcome is obtained for Δh/w roughly between 0.45 and 0.6. Qualitatively, if the bump is widened (i.e.,* w* increases), a complementary increase in its“height” (i.e.,* R**α*) is needed for the bump to serve its intended purpose. While easily understood, we recognize that Δh/w is simply a proxy for γ (the local Σ power-law index; see Section 2.3) at the steepest point along the interior side of the pressure bump, which is the true factor controlling its function.

Regime boundaries (where Δh/w ∼ 0.6 and 0.45) are clearly “soft” considering simulation outcomes in their vicinity. Regarding the former, it is clear that simulations for which Δh/w < 0.6 can still result in instability. Close examination of R**α–w pairs corresponding to these simulations is hardly a meaningful exercise, as they reflect a confluence of assumed model parameters and initial conditions that yield the unfavorable outcome. While useful to first-order, Δh/w alone does not determine the final architecture of the system. Along the latter boundary are simulations resulting in four-body resonances distinct from the 6:3:2:1 chain described above. For w ≳ 1.5h0 (or R**α ≳ 2), these simulations (light green in Figure [3