Putting FreeBSD’s “power to serve” motto to the test.

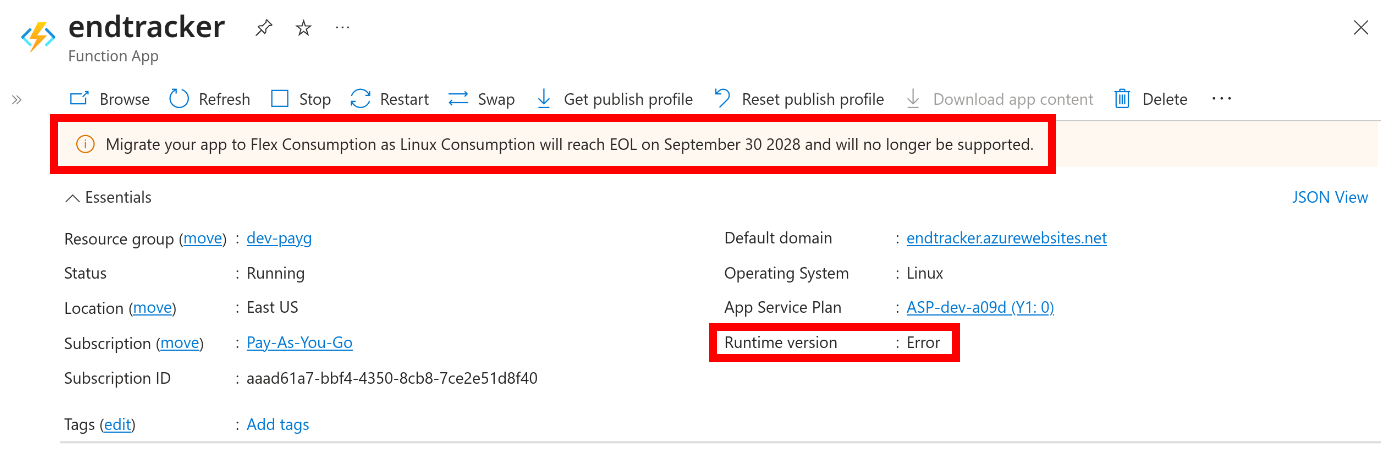

On Thanksgiving morning, I woke up to one of my web services being unavailable. All HTTP requests failed with a “503 Service unavailable” error. I logged into the console, saw a simplistic “Runtime version: Error” message, and was not able to diagnose the problem.

I did not spend a lot of time trying to figure the issue out and I didn’t even want to contact the support black hole. Because… there was something else hidden behind an innocent little yellow warning at the top of the dashboard:

Migrate your app to Flex Consumption as Linux Consumption will reach EOL on September 30 2028 and will no longer be supported.

I had known for a few weeks now, while trying to set up a new app, that all of my Azure Functions apps were on…

Putting FreeBSD’s “power to serve” motto to the test.

On Thanksgiving morning, I woke up to one of my web services being unavailable. All HTTP requests failed with a “503 Service unavailable” error. I logged into the console, saw a simplistic “Runtime version: Error” message, and was not able to diagnose the problem.

I did not spend a lot of time trying to figure the issue out and I didn’t even want to contact the support black hole. Because… there was something else hidden behind an innocent little yellow warning at the top of the dashboard:

Migrate your app to Flex Consumption as Linux Consumption will reach EOL on September 30 2028 and will no longer be supported.

I had known for a few weeks now, while trying to set up a new app, that all of my Azure Functions apps were on death row. The free plan I was using was going to be decommissioned and the alternatives I tried didn’t seem to support custom handlers written in Rust. I still had three years to deal with this, but hitting a showstopper error pushed me to take action.

All of my web services are now hosted by the FreeBSD server in my garage with just a few tweaks to their codebase. This is their migration story.

How did I get here?

Back in 2021, I had been developing my EndBASIC language for over a year and I wanted to create a file sharing service for it. Part of this was to satisfy my users, but another part was to force myself into the web services world as I felt “behind”.

At that time, I had also been at Microsoft for a few months already working on Azure Storage. One of the perks of the job was something like $300 of yearly credit to deploy stuff on Azure for learning purposes. It was only “natural” that I’d pick Azure for what I wanted to do with EndBASIC.

Now… $300 can be plentiful for a simple app, but it can also be paltry. Running a dedicated VM would eat through this in a couple of months, but the serverless model offered by Azure Functions with its “infinite” free tier would go a long way. I looked at their online documentation, found a very good guide on how to deploy Rust-native functions onto a Linux runtime, and… I was sold.

I quickly got a bare bones service up and running on Azure Functions and I built it up from there. Based on these foundations, I later developed a separate service for my own site analytics (poorly named EndTRACKER), and I recently started working on a new service to provide secure auto-unlock of encrypted ZFS volumes (stay tuned!).

And, for the most part, the experience with Azure has been neat. I learned a bunch and I got to a point where I had set up “push on green” via GitHub Actions and dual staging vs. prod deployments. The apps ran completely on their own for the last three years, a testament to the stability of the platform and to the value of designing for testability. Until now that is.

The cloud database

Compute-wise, I was set: Azure Functions worked fine as the runtime for my apps’ logic and it cost pennies to run, so the $300 was almost untouched. But web services aren’t made of compute alone: they need to store data, which means they need a database.

My initial research in 2021 concluded that the only option for a database instance with a free plan was to go with, no surprise, serverless Microsoft SQL Server (MSSQL). I had never used Microsoft’s offering but it couldn’t be that different from PostgreSQL or MySQL, could it?

Maybe so, but I didn’t get very far in that line of research. The very first blocker I hit was that the MSSQL connection required TLS and this hadn’t been implemented in the sqlx connector I chose to use for my Rust-based functions. I wasted two weeks implementing TLS support in sqlx (see PR #1200 and PR #1203) and got it to work, but that code was not accepted upstream because it conflicted with their business strategy. Needless to say, this was disappointing because getting that TlsStreamWrapper to work was a frigging nightmare. In any case, once I passed that point, I started discovering more missing features and bugs in the MSSQL connector, and then I also found some really weird surprises in MSSQL’s dialect of SQL. TL;DR, this turned into a dead end.

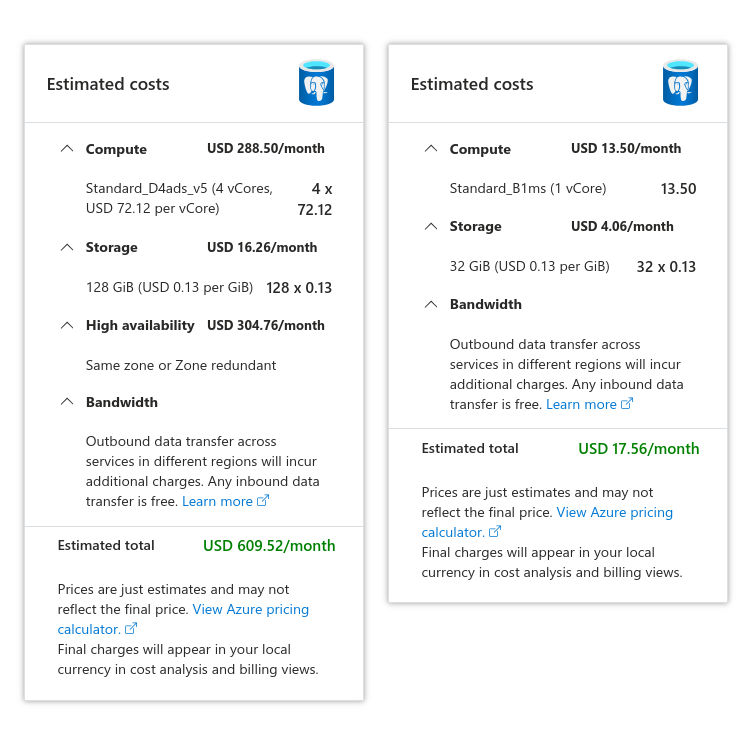

On the left, the default instance and cost selected by Azure when choosing to create a managed PostgreSQL server today. On the right, minimum possible cost after dialing down CPU, RAM, disk, and availability requirements.

On the left, the default instance and cost selected by Azure when choosing to create a managed PostgreSQL server today. On the right, minimum possible cost after dialing down CPU, RAM, disk, and availability requirements.

I had no choice other than to provision a full PostgreSQL server on Azure. Their onboarding wizard tried to push me towards a pretty beefy and redundant instance that would cost over $600 per month when all I needed was the lowest machine you could get for the amount of traffic I expected. Those options were hidden under a “for development only” panel and riddled with warnings about no redundancy, but after I dialed all the settings down and accepted the “serious risks”, I was left with an instance that’d cost $15 per month or so. This fit well well within the free yearly credit I had access to, so that was it.

The outage and trigger

About two months ago, I started working on a new service to securely auto-unlock ZFS encrypted volumes (more details coming). For this, I had to create a new Azure Functions deployment… and I started seeing the writing on the wall. I don’t remember the exact details, but it was really difficult to get the creation wizard to provision me the same flex plan I had used for my other services, and it was warning me that the selected plan was going to be axed in 2028.

At the time of this writing, 2028 is still three years out and this warning was for a new service I was creating. I didn’t want to consider migrating neither EndBASIC nor EndTRACKER to something else just yet. Until Thanksgiving, that was.

On Thanksgiving morning, I noticed that my web analytics had stopped working. All HTTP API requests failed with a “503 Service unavailable.” error but, interestingly, the cron-triggered APIs were still running in the background just fine and the staging deployment slot of the same app worked fine end-to-end as well. I tried redeploying the app with a fresh binary, thinking that a refresh would fix the problem, but that was of no use. I also poked through the dashboard trying to figure out what “Runtime version: Error” would be about, making sure the version spec in host.json was up-to-date, and couldn’t figure it out either.

Summary state of my problematic Azure Functions deployment. Note the cryptic runtime error along with the subtle warning at the top about upcoming deprecations.

Summary state of my problematic Azure Functions deployment. Note the cryptic runtime error along with the subtle warning at the top about upcoming deprecations.

So… I had to get out of Azure Functions, quick.

Not accidentally, I had bought a second-hand, over-provisioned ThinkStation (2x36-core Xeon E5-2697, 64 GB of RAM, a 2 TB NVMe drive, and a 4x4 TB HDD array) just two years back. The justification I gave myself was to use it as my development server, but I had this idea in the back of my mind to use it to host my own services at some point. The time to put it to serving real-world traffic with FreeBSD 14.x had come.

From serverless to serverful

The way you run a serverless Rust (or Go) service on Azure Functions is by creating a binary that exposes an HTTP server on the port provided to it by the FUNCTIONS_CUSTOMHANDLER_PORT environment variable. Then, you package the binary along a set of metadata JSON files that tell the runtime what HTTP routes the binary serves and push the packaged ZIP file to Azure. From there on, the Azure Functions runtime handles TLS termination for those routes, spawns your binary server on a micro VM on demand, and redirects the requests to it.

By removing the Azure Functions runtime from the picture, I had to make my server binary stand alone. This was actually pretty simple because the binary was already an HTTP server: it just had to be coerced into playing nicely with FreeBSD’s approach to running services. In particular, I had to:

- Inject configuration variables into the server process at startup time. These used to come from the Azure Functions configuration page, and are necessary to tell the server where the database lives and what credentials to use.

- Make the service run as an unprivileged user, easily.

- Create a PID file to track the execution of the process so that the

rc.dframework could handle restarts and stop requests. - Store the logs that the service emits via stderr to a log file, and rotate the log to prevent local disk overruns.

Most daemons implement all of the above as features in their own code, but I did not want to have to retrofit all of these into my existing HTTP service in a rush. Fortunately, FreeBSD provides this little tool, daemon(8), which wraps an existing binary and offers all of the above.

This incantation was enough to get me going:

daemon \

-P /var/run/endbasic.pid \

-o /var/log/endbasic.log \

-H \

-u endbasic \

-t endbasic \

/bin/sh -c '

. /usr/local/etc/endbasic.conf

/usr/local/sbin/endbasic'

I won’t dive into the details of each flag, but to note: -P specifies which PID file to create; -o specifies where to store the stdout and stderr of the process; -H is required for log rotation (much more below); -u drops privileges to the given user; and -t specifies the “title” of the process to display in ps ax output.

The . /usr/local/etc/endbasic.conf trick was sufficient to inject configuration variables upon process startup, simulating the same environment that my server used to see when spawned by the Azure Functions runtime.

Hooking that up into an rc.d service script was then trivial:

#! /bin/sh

# PROVIDE: endbasic

# REQUIRE: NETWORKING postgresql

. /etc/rc.subr

name="endbasic"

command="daemon"

rcvar="endbasic_enable"

pidfile="/var/run/${name}.pid"

start_cmd="endbasic_start"

required_files="

/usr/local/etc/endbasic.conf

/usr/local/sbin/endbasic"

endbasic_start()

{

if [ ! -f /var/log/endbasic.log ]; then

touch /var/log/endbasic.log

chmod 600 /var/log/endbasic.log

chown endbasic /var/log/endbasic.log

fi

echo "Starting ${name}."

daemon \

-P "${pidfile}" \

-o /var/log/endbasic.log \

-H \

-u endbasic \

-t endbasic \

/bin/sh -c '

. /usr/local/etc/endbasic.conf

/usr/local/sbin/endbasic'

}

load_rc_config $name

run_rc_command "$1"

And with that:

sysrc endbasic_enabled="YES"

service endbasic start

Ta-da! I had the service running locally and listening to a local port determined in the configuration file.

As part of the migration out of Azure Functions, I switched to self-hosting PostgreSQL as well. This was straightforward but required a couple of extra improvements to my web framework: one to stop using a remote PostgreSQL instance for tests(something I should have done eons ago), and another to support local peer authentication to avoid unnecessary passwords.

Log rotation

In the call to daemon above, I briefly mentioned the need for the -H flag to support log rotation. What’s that about?

You see, in Unix-like systems, when a process opens a file, the process holds a handle to the open file. If you delete or rename the file, the handle continues to exist exactly as it was. This has two consequences:

- If you rename the file, all subsequent reads and writes go to the new file location, not the old one.

- If you delete the file, all subsequent reads and writes continue to go to disk but to a file you cannot reference anymore. You can run out of disk space and, while

dfwill confirm the fact,duwill not let you find what file is actually consuming it!

For a long-running daemon that spits out verbose logs, writing them to a file can become problematic because you can end up running out of disk space. To solve this problem, daemons typically implement log rotation: a mechanism to keep log sizes in check by moving them aside when a certain period of time passes or when they cross a size threshold, and then only keeping the last N files around. Peeking into one of the many examples in my server, note how maillog is the “live” log where writes go to but there is a daily maillog.N.bz2 archive for up to a week:

$ ls -l /var/log/maillog*

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 4206 Dec 6 05:41 maillog

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 823 Dec 6 00:00 maillog.0.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 876 Dec 5 00:00 maillog.1.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 791 Dec 4 00:00 maillog.2.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 820 Dec 3 00:00 maillog.3.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 808 Dec 2 00:00 maillog.4.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 759 Dec 1 00:00 maillog.5.bz2

-rw-r----- 1 root wheel 806 Nov 30 00:00 maillog.6.bz2

$ █

Having all daemons implement log rotation logic on their own would be suboptimal because you’d have duplicate logic throughout the system and you would not be able to configure policy easily for them all. This is where newsyslog(8) on FreeBSD (or logrotate(8) on Linux) comes into play.

newsyslog is a tool that rotates log files based on criteria such as size or time and optionally compresses them. But remember: the semantics of open file handles mean that simply renaming log files is insufficient! Once newsyslog takes action and moves a log file aside, it must ensure that the process that was writing to that file closes the file handle and reopens it so that writes start going to the new place. This is typically done via sending a SIGHUP to the daemon, and is why we need to pass -H to the daemon call. To illustrate the sequence:

- The system starts a service via

daemonand redirects logs to/var/log/service.log. newsyslogruns and determines that/var/log/service.logneeds to be rotated because a day has passed.newsyslogrenames/var/log/service.logto/var/log/service.log.0and creates a new and empty/var/log/service.log. At this pointdaemonis still writing to/var/log/service.log.0!newsyslogsends aSIGHUPto thedaemonprocess.- The

daemonprocess closes its file handle for the log, reopens/var/log/service.log(which is the fresh new log file), and resumes writing. newsyslogcompresses the/var/log/service.log.0file for archival now that it’s quiesced.

Configuring newsyslog is easy, but cryptic. We can create a service-specific configuration file under /usr/local/etc/newsyslog.d/ that provides entries for our service, such as:

/var/log/endbasic.log endbasic:wheel 600 7 * @T00 JC /var/run/endbasic.pid

I’ll leave you to the manpage to figure out what the 7 * @T00 JC magic is (but in short, it controls retention count, rotation schedule, and compression).

TLS termination

As I briefly mentioned earlier, the Azure Functions runtime was responsible for TLS termination in my previous setup. Without such a runtime in place, I had to configure TLS on my own in my HTTP server… or did I?

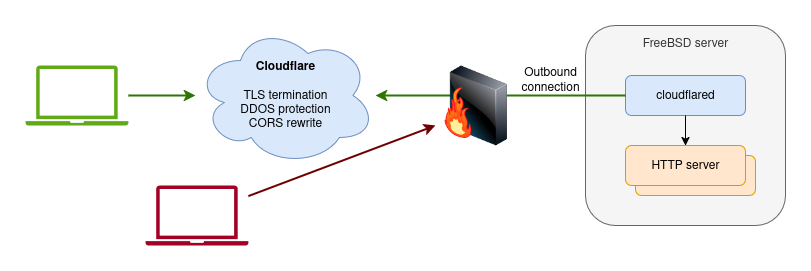

I had been meaning to play with Cloudflare Tunnels for a while given that I already use Cloudflare for DNS. Zero Trust Tunnels allow you to expose a service without opening inbound ports in your firewall. The way this works is by installing the cloudflared tunnel daemon on your machine and configuring the tunnel to redirect certain URL routes to an internal address (typically http://localhost:PORT). Cloudflare then acts as the frontend for the requests, handles TLS termination and DDOS protection, and then redirects the request to your local service.

Interactions between client machines, Cloudflare servers, the cloudflared tunnel agent, and the actual HTTP servers I wrote.

Interactions between client machines, Cloudflare servers, the cloudflared tunnel agent, and the actual HTTP servers I wrote.

The obvious downside of relying on someone else to do TLS termination instead of doing it yourself on your own server is that they can intercept and modify your traffic. For the kinds of services I run this isn’t a big deal for me, and the simplicity of others dealing with certificates is well welcome. Note that I was already offloading TLS termination to Azure Functions anyway, so this isn’t a downgrade in security or privacy.

CORS

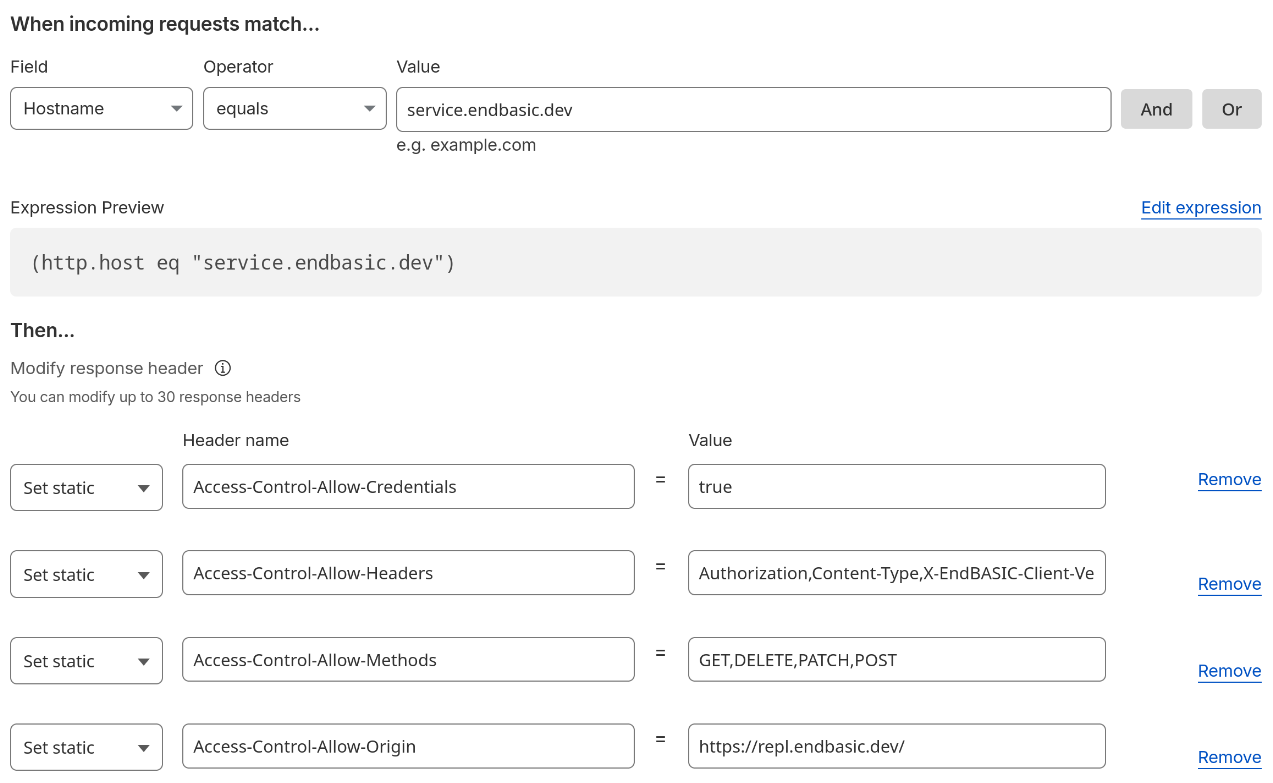

But using Cloudflare as the frontend came with a little annoyance: CORS handling. You see: the services I run require configuring extra allowed origins, and as soon as I tried to connect to them via the Cloudflare tunnel, I’d get the dreaded “405 Method not allowed” error in the requests.

Before, I used to configure CORS orgins from the Azure Functions console, but no amount of peeking through the Cloudflare console showed me how to do this for my tunneled routes.

At some point during the investigation, I assumed that I had to configure CORS on my own server. I’m not sure how I reached that bogus conclusion, but I ended up wasting a few hours implementing a configuration system for CORS in my web framework. Nice addition… but ultimately useless.

I had not accounted for the fact that because Cloudflare acts as the frontend for the services, it is the one responsible for handling the pre-flight HTTP requests necessary for CORS. In turn, this means that Cloudflare is where CORS needs to be configured but there is nothing “obvious” about configuring CORS in the Cloudflare portal.

AI to the rescue! As skeptical as I am of these tools, it’s true that they work well to get answers to common problems—and figuring out how to deal with CORS in Cloudflare was no exception. They told me to configure a transformation rule that explicitly sets CORS response headers for specific subdomains, and that did the trick:

Sample rule configuration on the Cloudflare portal to rewrite CORS response headers.

Sample rule configuration on the Cloudflare portal to rewrite CORS response headers.

Even though AI was correct in this case, the whole thing looked fishy to me, so I did spend time reading about the inner workings of CORS to make sure I understood what this proposed solution was about and to gain my own confidence that it was correct.

Results of the transition

By now, my web services are now fully running on my FreeBSD machine. The above may have seemed complicated, but in reality it was all just a few hours of work on Thanksgiving morning. Let’s conclude by analyzing the results of the transition.

On the plus side, here is what I’ve gained:

Predictability: Running in the cloud puts you at the mercy of the upgrade and product discontinuation treadmill of big cloud providers. It’s no fun to have to be paying attention to deprecation messages and adjust to changes no matter how long the deadlines are. FreeBSD also evolves, of course, but it has remained pretty much the same over the last 30 years and I have no reason to believe it’ll significantly change in the years to come.

Performance: My apps are so much faster now it’s ridiculous. The serverless runtime of Azure Functions starts quickly for sure, but it just can’t beat a server that’s continuously running and that has hot caches at all layers. That said, I bet the real difference in performance for my use case comes from collocating the app servers with the database, duh.

Ease of management: In the past, having automated deployments via GitHub Actions to Azure Functions was pretty cool, not gonna lie. But… being now able to deploy with a trivial sudo make install, perform administration PostgreSQL tasks with just a sudo -u postgres psql, and inspecting logs trivially and quickly by looking at /var/log/ beats any sort of online UI and distributed system. “Doesn’t scale” you say, but it scales up my time.

Cost: My Azure bill has gone from $20/month, the majority of which was going into the managed PostgreSQL instance, to almost zero. Yes, the server I’m running in the garage is probably costing me the same or more in electricity, but I was running it anyway already for other reasons.

And here is what I’ve lost (for now):

Availability (and redundancy): The cloud gives you the chance of very high availability by providing access to multiple regions. Leveraging these extra availability features is not cheap and often requires extra work, and I wasn’t taking advantage of them in my previous setup. So, I haven’t really decreased redundancy, but it’s funny that the day right after I finished the migration, I lost power for about 2 hours. Hah, I think I hadn’t suffered any outages with Azure other than the one described in this article.

A staging deployment: In my previous setup, I had dual prod and staging deployments (via Azure Functions slots and separate PostgreSQL databases—not servers) and it was cool to deploy first to staging, perform some manual validations, and then promote the deployment to prod. In practice, this was rather annoying because the deployment flow was very slow and not fully automated (see “manual testing”), but it indeed saved me from breaking prod a few times.

Auto-deployments: Lastly and also in my previous setup, I had automated the push to staging and prod by simply updating tags in the GitHub repository. Once again, this was convenient, but the biggest benefit of it all was that the prod build process was “containerized” and not subject to environmental interference. I’d very well set up a cron job or webhook-triggered local service that rebuilt and deployed my services on push… but it’s now hard to beat the simplicity of sudo make install.

None of the above losses are inherent to self-hosting, of course. I could provide alternatives for them all and at some point I will; consider them to-dos!