The source of this tutorial is available on GitHub. Feel free to use that source repository to contact the author with questions, discuss possible improvements or report mistakes.

Virtual machines provide a level of isolation unattainable by any flavor of Linux container. Virtualization technologies are widely adopted in the industry as a response to stringent security requirements, particularly in environments that share hardware between multiple tenants and must guarantee opaque boundaries between those tenants. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that cloud hyperscalers provide access to compute in various forms of virtual machines[1](https://labs.iximiuz.com/tutorials/unikernels-i…

The source of this tutorial is available on GitHub. Feel free to use that source repository to contact the author with questions, discuss possible improvements or report mistakes.

Virtual machines provide a level of isolation unattainable by any flavor of Linux container. Virtualization technologies are widely adopted in the industry as a response to stringent security requirements, particularly in environments that share hardware between multiple tenants and must guarantee opaque boundaries between those tenants. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that cloud hyperscalers provide access to compute in various forms of virtual machines1 rather than some abstraction on top of a shared OS kernel.

But reaping the security benefits of virtual machines typically requires compromising on performance aspects. Cold booting an entire operating system takes significantly more time than spawning an OS process, which hinders dynamic application scaling. Also with each VM’s kernel making independent scheduling decisions on top of the same hardware resources (CPU, memory, network, GPUs, ...), running multiple general-purpose operating systems such as Linux side by side requires smart hypervisors in order to distribute those resources optimally2.

You will often encounter the term "Micro VM" to describe a type of virtual machine that attempts to address the aforementioned limitations by reducing their memory footprint through restricted device support and guest3 functionalities. While this approach demonstrates measurable improvements to boot times, the guest itself still carries the overhead of a full, general-purpose operating system.

Unikernels propose a solution to that exact problem.

Throughout this tutorial, you will learn what a unikernel is made of and even build one yourself. You will be guided throughout the steps required for running this unikernel on any Linux host, then package it as an OCI image that can be run by Docker.

Requirements

- Notions about virtualization: what is a virtual machine, a hypervisor.

- A high level understanding of how an OS process interacts with its kernel: libc, syscalls.

- A good understanding about the subsystems involved in the composition of a Linux container: namespaces, cgroups, CNI.

What Is a Unikernel?

Core Principles

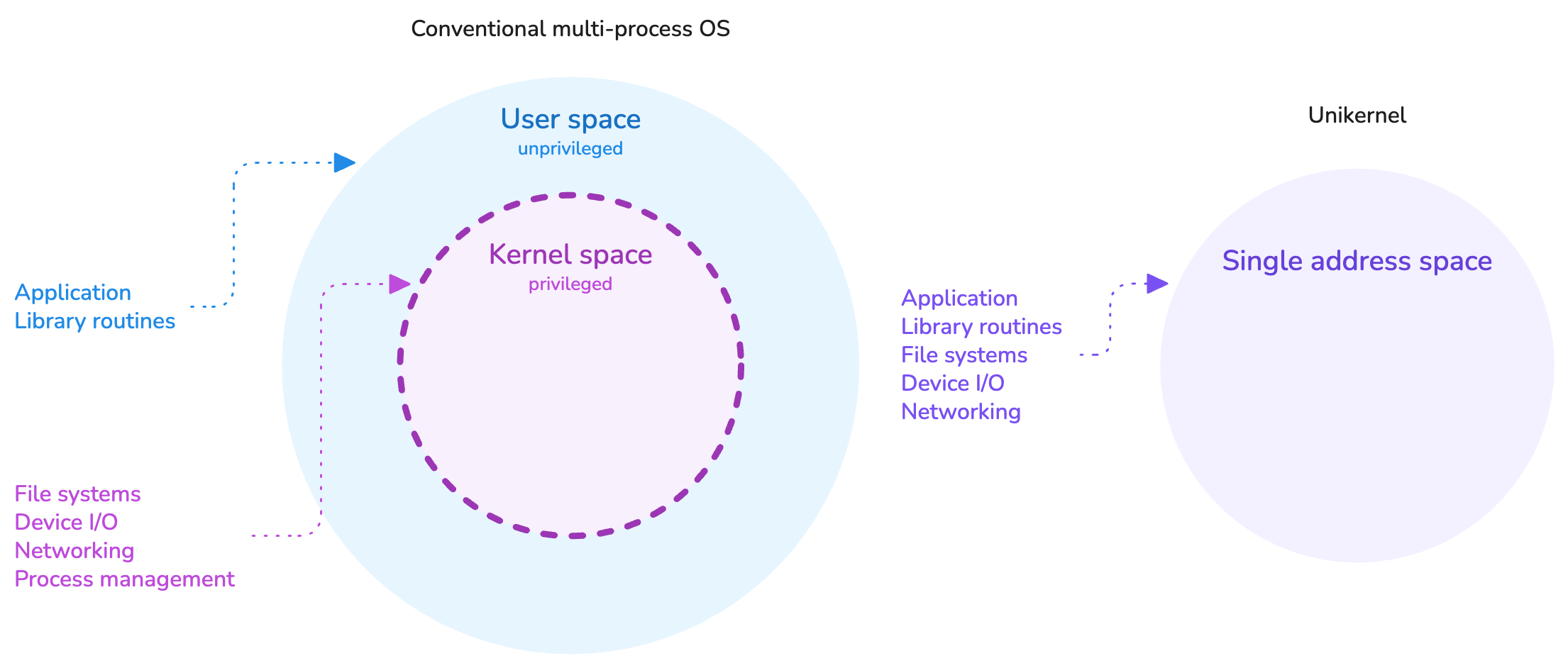

In essence, a unikernel is a highly specialized type of kernel that is tailored for running one application, and that application specifically. By this property, a unikernel is capable of running in a single address space, where the usual distinction between kernel and user spaces does not exist. The application is the kernel, as much as the kernel is the application.

This design avoids paying the performance penalty of switching contexts on system calls between the user space and the kernel space, a behavior that is unavoidable in traditional operating systems. It allows a direct and quicker access to the hardware.

Unikernels operate in a single address space.

There exists different types of unikernel projects. Some are tailored to run applications written in specific programming languages, others are more versatile. Some are monolithic, others are modular. Some require compiling and linking the application in a special way, others are able to run unmodified ELF executables.

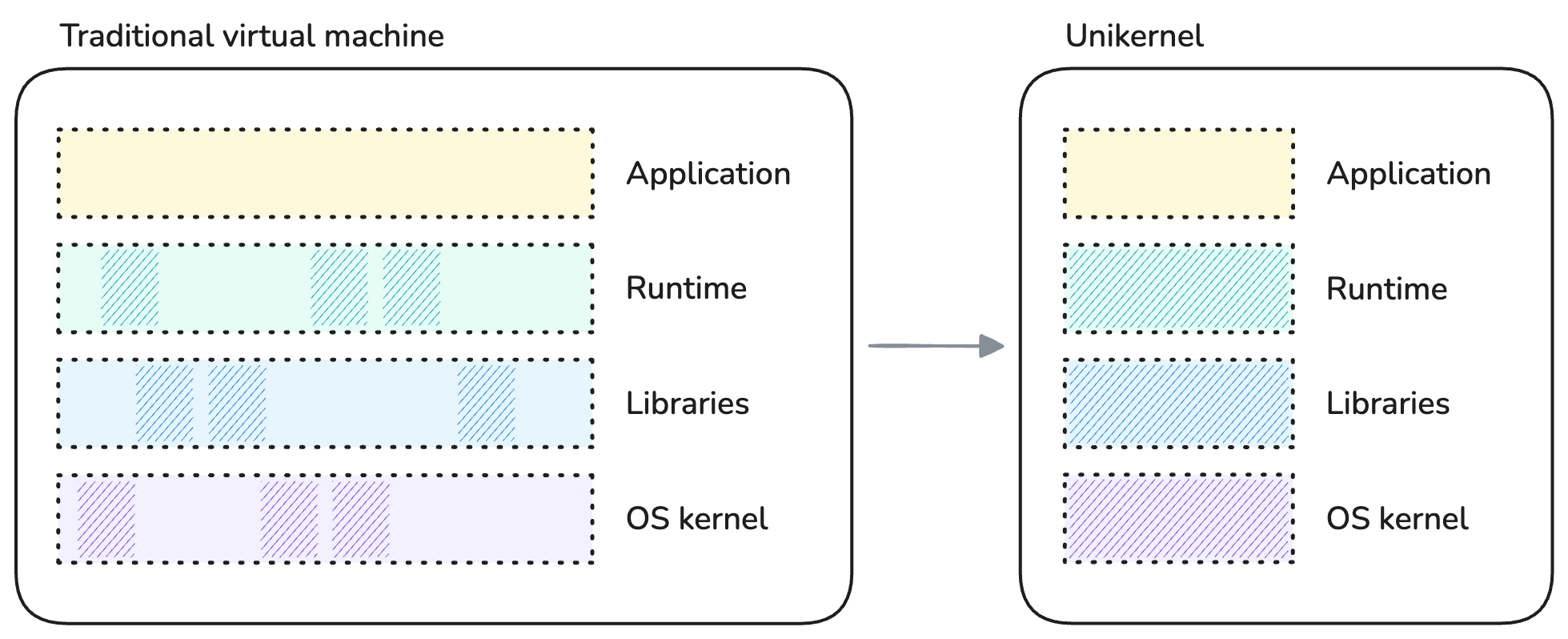

Despite those differences, all strive to achieve specialization in a similar way: by selecting only the components of the software stack which are relevant to the application. For instance, there is no use for disk filesystem drivers in a piece of software which interacts solely with the network and does not write any data to disk. Likewise, because the unikernel is a single application, it does not require any user management or scheduling facilities. These become opportunities for reducing the software footprint by cutting on bloat, also reducing its attack surface by extension.

We often refer to the unikernel paradigm as "library operating systems".

Specializing a unikernel by components selection.

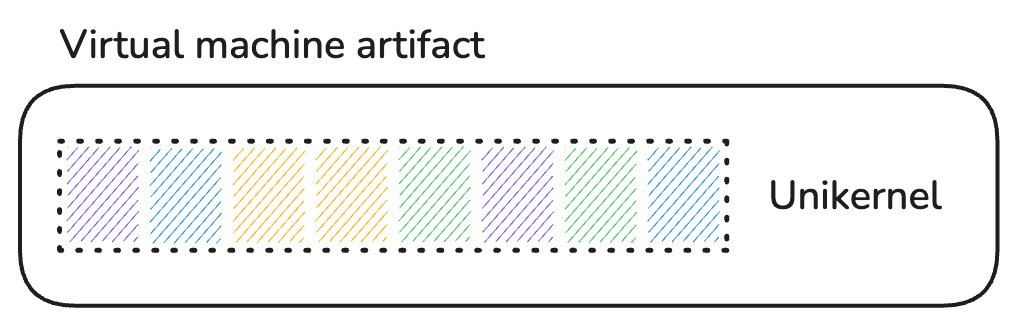

The artifact produced by building a unikernel is a kernel executable that comprises the application, along with only the parts of the OS kernel, libraries and possible runtime that were selected for that application. Because a unikernel is meant to be materialized as a virtual machine, the produced artifact is specific to the target hypervisor (KVM4, Xen5, VMware, ...) and CPU architecture.

Final unikernel artifact.

In summary, unikernels:

- Operate in a drastically minimized software stack without separation between kernel and user spaces.

- Have a smaller memory footprint and attack surface than a Linux process.

- Do not share any kernel components with the host.

- Benefit from the strong isolation of a virtual machine.

As a result, unikernels offer increased security and performance compared to a containerized Linux process.

Trade-Offs

It would feel dishonest to praise unikernels for their many benefits without acknowledging some of their limitations.

Nowadays, the comparison of unikernels with Linux containers seems unavoidable, therefore the aspects enumerated below focus deliberately on use-cases that a container typically enables and which presents challenges when running the same application as a unikernel.

No Shell, No Users

We are starting with some fully embraced bait; the absence of shells and users is absolutely desired for reducing the attack surface of applications.

Yet, when comes the need to troubleshoot a misbehaving live application it is hard to beat the convenience of containers. Need to use a specific tool but the container’s root filesystem is only one statically linked executable? No problem, attach your favorite debugging shell to the namespaces of the container, become root if you please, and off you go.

With a unikernel? You better be sure that the application has comprehensive observability facilities built-in.

Single Process

Unikernels are inherently single-process OSes due to their single address space design.

A range of applications use the POSIX fork system call to create child processes such as additional workers, data snapshotters, etc. Running such applications as unikernels present challenges and require trade-offs. Some notable examples:

- The PostgreSQL database server has process-based architecture rather than using threads.

- The most widely used worker (MPM) of Apache HTTPd implements a hybrid multi-process / multi-threaded server.

- The Redis in-memory cache persists data on disk using a child process.

Containers being regular OS processes, they do not suffer from such limitation.

No Standardization

Unikernels are still considered a niche technology despite building on concepts developed in the late 1990s. As such, they lack the standardization that emerges once a technology achieves a certain degree of maturity. This means that there is currently no compatibility whatsoever between unikernel projects and their associated tooling.

Interestingly, compatibility with container-centric and cloud-native tooling is limited but not nonexistent, as you will discover later in this tutorial.

This lack of standardization is no different from the early days of containers, which weren’t standardized either until several years into the existence of Docker containers.

Knowledge Requirements

Because unikernels are purpose-built and combine both the user and kernel code, they generally require a deeper knowledge about the software stack than is required for building conventional application artifacts. Porting an application as a unikernel may require specialist knowledge from the runtime through the kernel interfaces all the way down to the hardware.

As previously mentioned, there exists unikernel projects that can run unmodified ELF executables in a binary-compatible mode (POSIX compliant). Even though these do not enable the full, uncompromised performance and security benefits of purpose-built unikernels, they preserve a number of those benefits over a general-purpose, multi-user operating system kernel like Linux. They also bring the process of building a unikernel closer to the one of assembling a container image. Win-win.

Limited Inter-Process Communications

Finally, one limitation that stems from the virtual machine model and not the unikernel architecture in itself is the lack of supporting facilities for inter-process communications. Without a shared kernel to provide such facilities, applications running as unikernels must communicate over the network or via channels provided by their underlying hypervisor.

Containers allow multiple processes to be confined together and communicate over UNIX domain sockets, POSIX message queues, a loopback network interface, OS signals, etc.

Building the Unikernel

Now that you are equipped with general knowledge about unikernels, let’s begin with the hands-on part of the tutorial, shall we?

In this tutorial, you are going to build the Nginx web server as a Unikraft unikernel, from sources.

Nginx is a classic example of server application that is both incredibly widespread6 and easy to interact with.

The Unikraft kernel was chosen for this tutorial because it ticks the following boxes:

- Comprehensive implementation of the library OS concept with a modular design that supports both porting from sources and binary compatibility.

- Supported by some of the OCI7 tooling used later in this tutorial.

The playground box is pre-initialized with the following two directories inside your HOME:

ls -p

nginx/ sources/

nginx/is your workspace for building the Nginx application as a Unikraft unikernel.sources/contains the source code of the Unikraft core, of Nginx itself (as a thin Unikraft library) and of additional libraries required by the Nginx application.

Start by changing your working directory to nginx/. You will remain in there throughout most of this tutorial:

cd nginx

This directory contains a few files which are solely responsible for configuring and building the unikernel:

ls -p1 --group-directories-first

oci/

rootfs/

workdir/

Config.uk

Makefile

Makefile.uk

qemu-x86_64.defconfig

Use the tabs below for a description of the purpose of each of these files:

qemu-x86_64.defconfig

Config.uk

workdir

Makefile

A file in which kernel options with non-default values are specified.

Options which are specific to our flavor of the unikernel are enabled in this file and will be merged with the defaults of the Unikraft kernel:

- The target platform/hypervisor: KVM.

- Our preference for printing kernel messages at the info level (only errors are printed by default).

- Some filesystem implementation (embedded initrd).

qemu-x86_64.defconfig

CONFIG_PLAT_KVM=y

CONFIG_LIBUKDEBUG_PRINTK_INFO=y

CONFIG_LIBVFSCORE_AUTOMOUNT_CI=y

CONFIG_LIBVFSCORE_AUTOMOUNT_CI_EINITRD=y

Kernel Configuration

First, a kernel needs a configuration, and a unikernel in no exception. You have already encountered the qemu-x86_64.defconfig file, you are now going to generate the full kernel configuration based on those few customized values:

UK_DEFCONFIG=$PWD/qemu-x86_64.defconfig make defconfig

MAKE kconfig

...

#

# configuration written to /home/laborant/nginx/.config

#

This command should have generated a file named .config inside the workspace:

git status --short

?? .config

It contains an aggregation of all the kernel options explicitly or implicitly selected inside the workspace, merged with the defaults from the Unikraft core.

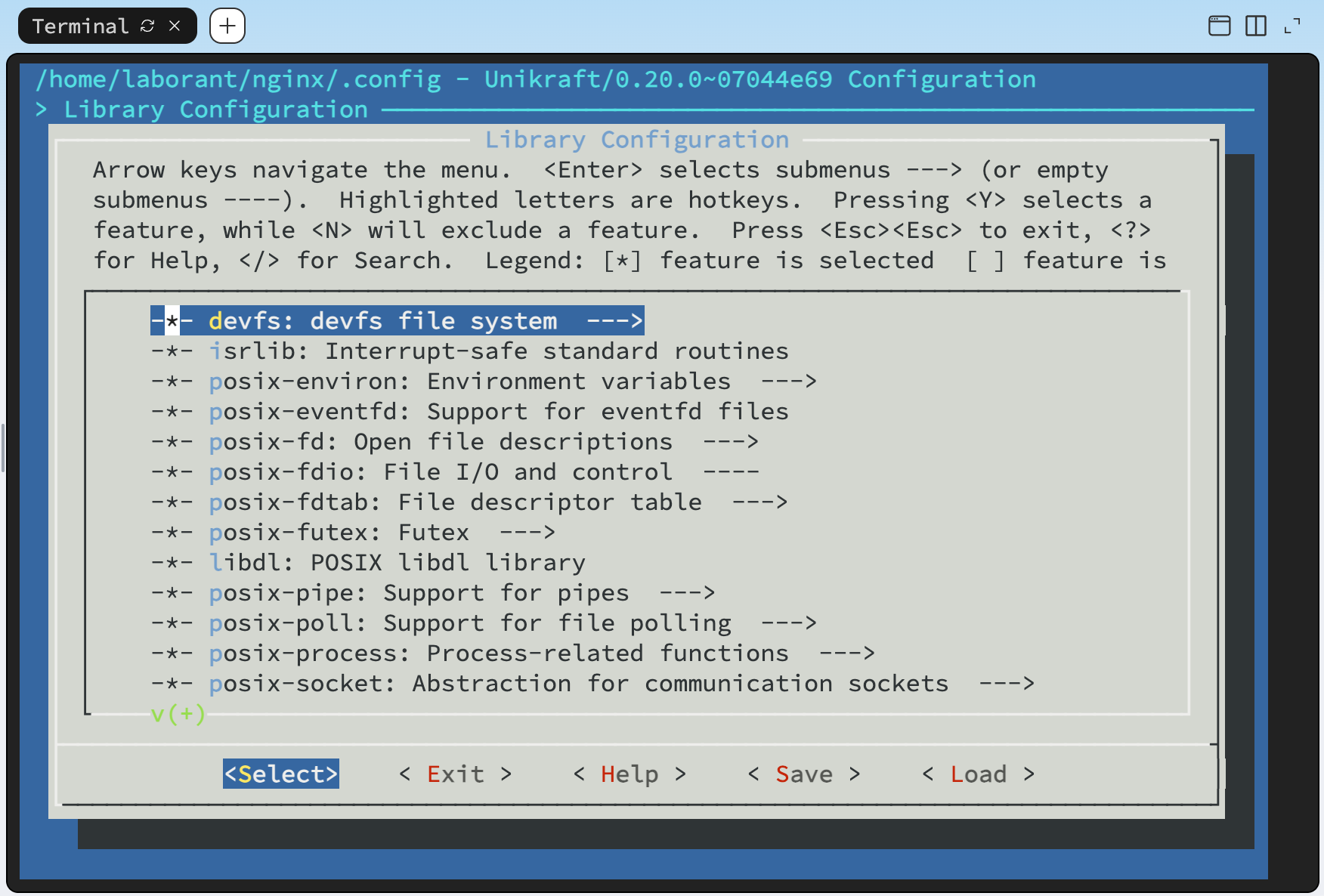

Configuration TUI

Instead of invoking the defconfig goal, you could have selected kernel options via a terminal-based kernel configuration interface.

Since your .config file is already generated, opening this interface will display the options that were selected by the defconfig goal. Give it a try! If you have ever built the Linux kernel from sources this should look familiar, even spark a bit of nostalgia :)

(You might have to expand the side panel for your web-based terminal to have large enough dimensions.)

make menuconfig

With the kernel configuration generated, you are now ready to proceed with the build. Let’s go:

make -j $(nproc)

The build process goes through a few steps, including fetching the source code of the libraries and application (Nginx) which are not yet cached locally:

...

WGET libmusl: https://www.musl-libc.org/releases/musl-1.2.3.tar.gz

...

WGET libnginx: http://nginx.org/download/nginx-1.15.6.tar.gz

Unfortunately, about 10 seconds in, an error comes and ruins the party already:

make[3]: *** No rule to make target '/home/laborant/nginx/initrd.cpio', needed by '/home/laborant/nginx/workdir/build/libvfscore/einitrd.o'. Stop.

This is part of the tutorial and a good segue into some peculiarity about the unikernel you are building.

Files Access

If you take a step back and think about what a typical application package contains—be it an OS package or a container image—you might be able to guess where we are heading. Let’s take a look at the files included with the nginx-common package of the playground box’s distribution:

dpkg -L nginx-common

/etc/default/nginx

/etc/init.d/nginx

/etc/logrotate.d/nginx

/etc/nginx/fastcgi.conf

/etc/nginx/fastcgi_params

/etc/nginx/koi-utf

/etc/nginx/koi-win

/etc/nginx/mime.types

/etc/nginx/nginx.conf

/etc/nginx/sites-available/default

/usr/lib/systemd/system/nginx.service

/usr/share/apport/package-hooks/source_nginx.py

/usr/share/doc/nginx-common/changelog.Debian.gz

/usr/share/nginx/html/index.html

That’s right, a bunch of static resources. While some are support files for the playground’s Linux distribution (service definition, logrotate config, docs) others, such as the highlighted ones, are required by the Nginx application to function.

On any Linux system, exposing such files to an application is commonly accepted as storing the files on a mounted filesystem and giving read/write permissions on these files to the UNIX user that the application is going to run as. In a container image, those same files are either part of the root filesystem already, or bind mounted at run time to the root filesystem that the container pivots to.

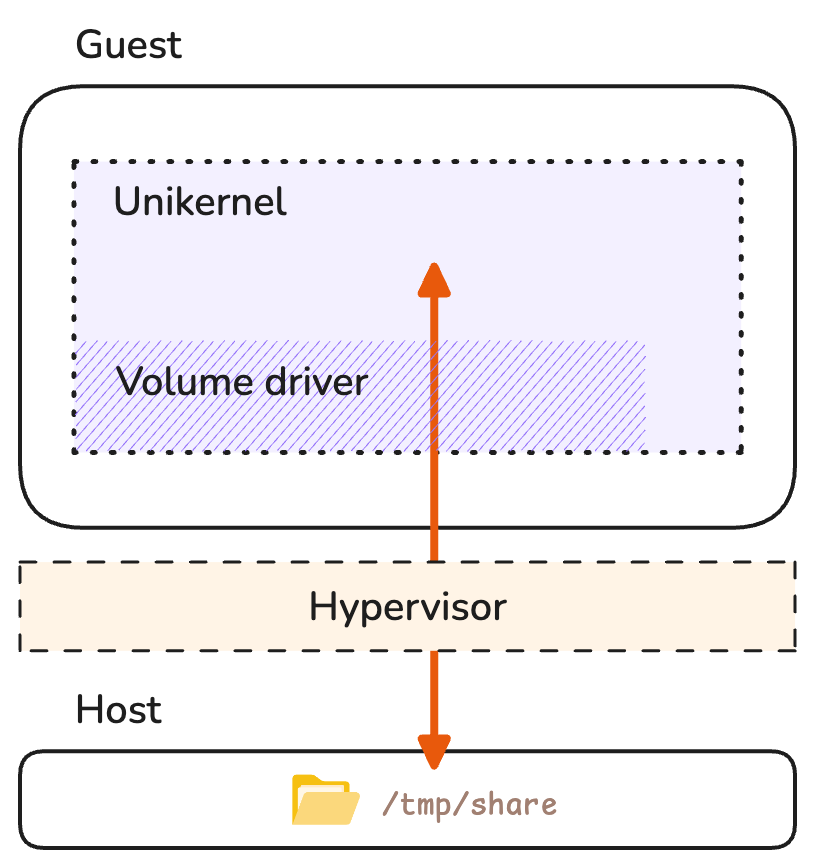

But our unikernel does not have access to a filesystem exposed through a shared host kernel, so those files must be provided to the application by different means. One option could have been to enable selected filesystem drivers via kernel options and share files from the host at run time through the target hypervisor, similarly to a bind mount on Linux.

Sharing files from the host over the 9p protocol.

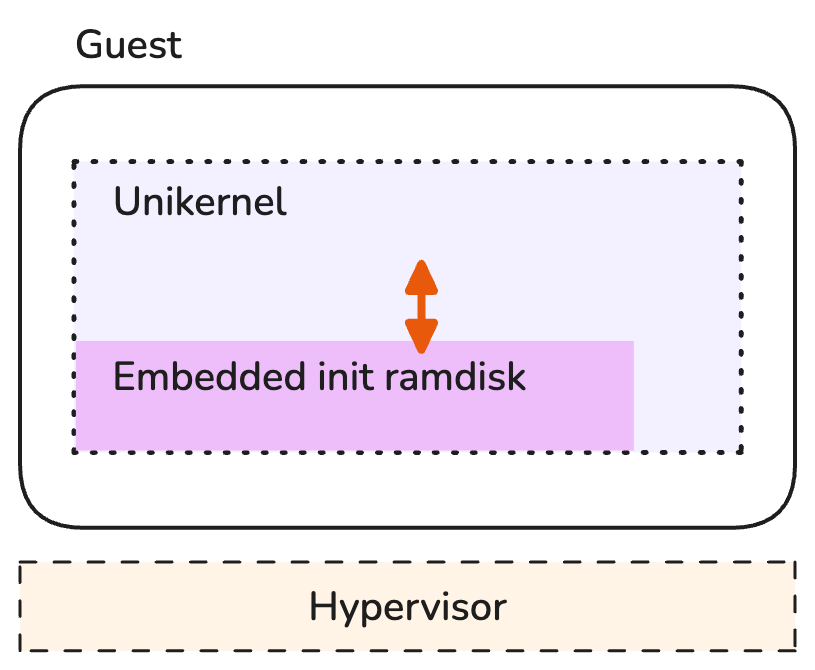

However, the option we selected in this tutorial is to embed the files in an initial ramdisk (initrd) using the kernel option CONFIG_LIBVFSCORE_AUTOMOUNT_CI_EINITRD=y (and related CONFIG_LIBVFSCORE_AUTOMOUNT_* configuration options). With this approach, the initial ramdisk is expanded into a root filesystem mounted as a read-write RAM-based filesystem (ramfs) upon booting the unikernel. A perfect solution for static and non-persistent files.

Embedding files into the unikernel as an init ramdisk.

We pinpointed earlier the lack of standardization across unikernel projects. The approaches proposed in this section are a demonstration of mechanisms and configurations which are highly Unikraft-specific and may or may not have an equivalent in other unikernels.

The files that need to be embedded are already part of your workspace and stored in the rootfs/ directory:

tree rootfs

rootfs/

└── nginx

├── conf

│ ├── mime.types

│ └── nginx.conf

├── html

│ └── index.html

└── logs

└── error.log

You need to convert the contents of this directory into a cpio8 archive. (Remember the error message?) The Unikraft core includes a support script which achieves just that:

workdir/unikraft/support/scripts/mkcpio initrd.cpio rootfs

The result is an archive named initrd.cpio containing all the files staged for embedding into the unikernel artifact at build time.

git status --short

?? .config

?? initrd.cpio

The cpio archive format

The format of a cpio archive isn’t that different from that of a tarball. Files are merely concatenated with their contents separated by some headers and metadata.

You can print the contents of the generated initrd.cpio using the following command and verify that it matches that of the rootfs/ directory:

bsdcat initrd.cpio

Kernel Build

You should now have all required resources sorted out:

.config– a kernel configuration.initrd.cpio– an init ramdisk for loading a root file system with a few static files into memory.

Let’s try building the unikernel one more time:

make -j $(nproc)

After about 2 minutes, you should see the build succeed with a final linking and stripping of the build artifacts:

...

OBJCOPY libmusl.o

LD nginx_qemu-x86_64.dbg

SCSTRIP nginx_qemu-x86_64

UKBI nginx_qemu-x86_64.bootinfo

MULTIBT nginx_qemu-x86_64.multiboot

make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/laborant/sources/unikraft'

All files resulting from the build are written to the build/ directory. The one without an extension in the list below is the kernel:

git status --short

?? .config

?? initrd.cpio

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.bootinfo

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.bootinfo.cmd

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.cmd

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.dbg

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.dbg.cmd

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.dbg.gdb.py

?? workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64.multiboot.cmd

Unikraft kernel’s naming convention

The base name of the generated kernel artifacts follows the naming convention:

$(CONFIG_UK_NAME)_$(KVM_VMM)-$(CONFIG_UK_ARCH)

You can verify that the file name nginx_qemu-x86_64 indeed matches the kernel configuration used during the build:

grep -E 'CONFIG_(UK_NAME|UK_ARCH|KVM_VMM)' --color .config

CONFIG_UK_ARCH="x86_64"

CONFIG_KVM_VMM_QEMU=y

# CONFIG_KVM_VMM_FIRECRACKER is not set

CONFIG_UK_NAME="nginx"

The format of this kernel is an ELF executable, just like the Linux kernel that your playground box is currently running on:

Nginx unikernel

Linux kernel

file workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64

workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped

One thing should be particularly striking about this artifact: its small size. The Nginx application and all the OS components required for running it fit into... less than 2 MB!

du -h workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64

2.0M workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64

For comparison, on the playground box’s distribution the nginx binary, the GNU libc and the Linux kernel taken together weigh almost 60 MB:

du -hL /boot/vmlinux /usr/sbin/nginx /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6

56M /boot/vmlinux

1.3M /usr/sbin/nginx

2.1M /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6

Running the Unikernel

The kernel you just built can be run as a machine. A unikernel could technically boot on a physical machine (e.g. your laptop) providing that it was built with drivers compatible with its hardware. However, unikernels are largely meant to run as virtual machines rather than physical ones, as mentioned in the introduction to this tutorial. This is mostly for two reasons:

- One reason is that unikernels have such a minimal footprint that, in a majority of cases, it wouldn’t make a lot of sense to dedicate the entire hardware of one machine to just one of them.

- The second reason has to do with hardware compatibility. By targeting paravirtualized VirtIO9 devices for instance, a unikernel can indirectly support a lot of physical hardware while retaining its high performance guarantees.

A Note on Hypervisor Support

Your nginx_qemu-x86_64 kernel is suitable for the KVM hypervisor and its userspace component in the QEMU10 virtual machine manager (VMM). You will leverage both when running the unikernel on the playground box. Producing a unikernel for a different hypervisor (such as Xen) or a different VMM (such as Firecracker11) would have required different build time parameters (kernel options).

The KVM kernel module effectively turns the Linux host operating system into a type-1 hypervisor. To leverage this virtualization solution, the host’s CPU needs to support certain CPU instructions through virtualization extensions.

Existing CPU extensions for virtualization

Virtualization extensions for x86-based CPUs are denoted as:

- "SVM" on AMD CPUs, which stands for Secure Virtual Machine. Marketed as "AMD-V".

- "VT-x" on Intel CPUs, which stands for Virtual Machine Extensions.

You can check whether those extensions are enabled on the playground box by looking for the corresponding CPU flags:

grep -E 'svm|vmx' --color /proc/cpuinfo

The other requirement is that the host’s Linux kernel includes the kvm module, expectedly.

Both of those requirements can conveniently be checked using a single command: kvm-ok.

No KVM module is available inside iximiuz Labs playgrounds, whether kvm_amd nor kvm_intel, even though the CPU could support it:

sudo kvm-ok

INFO: /dev/kvm does not exist

HINT: sudo modprobe kvm_amd

INFO: Your CPU supports KVM extensions

KVM acceleration can be used

sudo modprobe kvm_amd

modprobe: FATAL: Module kvm_amd not found in directory /lib/modules/5.10.246

This is luckily not an obstacle, as QEMU is capable of running virtual machines without KVM support. Machines with emulated hardware do not offer the same performance as the ones with hardware-assisted virtualization, but this is totally acceptable in the context of this tutorial.

Simply omit any KVM-related flag such as -enable-kvm in the following command and you should be good to go.

Create and Run the Virtual Machine

Let’s now run the kernel as a freshly created virtual machine using QEMU. Notice the unikernel executable you built in the previous section passed as argument, as well as kernel command-line parameters pointing at one of the files from your previously generated cpio archive:

sudo qemu-system-x86_64 \

-nographic \

-m 64M \

-kernel workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64 \

-append '-c /nginx/conf/nginx.conf'

Interestingly, those kernel parameters do not look like typical OS kernel command-line parameters, and indeed they are not. Those parameters are Nginx command-line parameters! A unikernel has OS and application components built into a single kernel artifact, so this should hopefully make a lot of sense.

Should you need to pass parameters to the core kernel components, you would have to keep them separated from the application’s parameters with --, as follows:

netdev.ip= vfs.fstab= random.seed= -- -c /nginx/conf/nginx.conf

We will use this mechanism in the next section of this tutorial.

As soon as the virtual machine is created, its console output will be printed to your terminal, just like when booting a Linux box. It includes the BIOS messages and the unikernel’s boot messages:

SeaBIOS (version 1.16.3-debian-1.16.3-2)

iPXE (https://ipxe.org) 00:03.0 CA00 PCI2.10 PnP PMM+02FCAE00+02F0AE00 CA00

Booting from ROM..[ 0.000000] Info: [libukconsole] <console.c @ 176> Registered con0: COM1, flags: IO

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukconsole] <console.c @ 176> Registered con1: vgacons, flags: -O

[ 0.000000] Warn: [libukrandom_lcpu] <init.c @ 28> Could not initialize the HWRNG (-95)

[ 0.000000] Info: [libkvmplat] <memory.c @ 498> Memory 00fd00000000-010000000000 outside mapped area

[ 0.000000] Info: [libkvmplat] <setup.c @ 99> Switch from bootstrap stack to stack @0x11000

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 280> Unikraft constructor table at 0x2d1000 - 0x2d1058

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 289> Initialize memory allocator...

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukallocbbuddy] <bbuddy.c @ 658> Initialize binary buddy allocator 11000

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 348> Initialize the IRQ subsystem...

[ 0.000000] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 355> Initialize platform time...

[ 0.000000] Info: [libkvmplat] <tscclock.c @ 255> Calibrating TSC clock against i8254 timer

[ 0.100033] Info: [libkvmplat] <tscclock.c @ 276> Clock source: TSC, frequency estimate is 4192526940 Hz

[ 0.100962] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 359> Initialize scheduling...

[ 0.101289] Info: [libukschedcoop] <schedcoop.c @ 289> Initializing cooperative scheduler

[ 0.102603] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 392> Init Table @ 0x2d1058 - 0x2d1148

[ 0.103145] Info: [libukbus] <bus.c @ 133> Initialize bus handlers...

[ 0.103609] Info: [libukbus] <bus.c @ 135> Probe buses...

[ 0.104003] Info: [libukbus_pci] <pci_bus.c @ 158> PCI 00:00.00 (0600 8086:1237): <no driver>

[ 0.104582] Info: [libukbus_pci] <pci_bus.c @ 158> PCI 00:01.00 (0600 8086:7000): <no driver>

[ 0.105068] Info: [libukbus_pci] <pci_bus.c @ 158> PCI 00:02.00 (0300 1234:1111): <no driver>

[ 0.105559] Info: [libukbus_pci] <pci_bus.c @ 158> PCI 00:03.00 (0200 8086:100e): <no driver>

[ 0.106190] Info: [liblwip] <init.c @ 174> Initializing lwip

[ 0.107715] Warn: [liblwip] <init.c @ 460> No network interface attached!

[ 0.108323] Info: [libvfscore] <mount.c @ 122> VFS: mounting ramfs at /

[ 0.109350] Info: [libvfscore] <automount.c @ 558> Extracting initrd @ 0x26ed50 (7168 bytes, source: "embedded") to /...

[ 0.110007] Info: [libukallocregion] <region.c @ 187> Initialize allocregion allocator @ 0x374020, len 5136

[ 0.110719] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 248> Creating directory /.

[ 0.111433] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 253> Path exists, checking type

[ 0.111895] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 278> Path exists and is dir, doing chmod

[ 0.112514] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 357> ./nginx inode 144531 has more than 1 link (5)

[ 0.113055] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 248> Creating directory /./nginx

[ 0.113795] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 357> ./nginx/conf inode 144532 has more than 1 link (2)

[ 0.114352] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 248> Creating directory /./nginx/conf

[ 0.115256] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 194> Extracting /./nginx/conf/nginx.conf (361 bytes)

[ 0.116722] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 194> Extracting /./nginx/conf/mime.types (5058 bytes)

[ 0.117400] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 357> ./nginx/logs inode 144537 has more than 1 link (2)

[ 0.117924] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 248> Creating directory /./nginx/logs

[ 0.118398] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 194> Extracting /./nginx/logs/error.log (0 bytes)

[ 0.118891] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 357> ./nginx/html inode 144535 has more than 1 link (2)

[ 0.119397] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 248> Creating directory /./nginx/html

[ 0.119875] Info: [libukcpio] <cpio.c @ 194> Extracting /./nginx/html/index.html (139 bytes)

[ 0.120493] Info: [libdevfs] <devfs_vnops.c @ 307> Mount devfs to /dev...VFS: mounting devfs at /dev

Powered by

o. .o _ _ __ _

Oo Oo ___ (_) | __ __ __ _ ' _) :_

oO oO ' _ `| | |/ / _)' _` | |_| _)

oOo oOO| | | | | (| | | (_) | _) :_

OoOoO ._, ._:_:_,\_._, .__,_:_, \___)

Kiviuq 0.20.0~07044e69

[ 0.139012] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 472> Pre-init table at 0x2d11e8 - 0x2d11e8

[ 0.139491] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 483> Constructor table at 0x2d11e8 - 0x2d11e8

[ 0.140007] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 498> Environment variables:

[ 0.140307] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 500> PATH=/bin

[ 0.140582] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 506> Calling main(3, ['workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64', '-c', '/nginx/conf/nginx.conf'])

[ 0.155220] Warn: [libposix_process] <rt_sigprocmask.c @ 72> __uk_syscall_r_rt_sigprocmask() stubbed

[ 0.155796] Warn: [libposix_process] <rt_sigaction.c @ 69> __uk_syscall_r_rt_sigaction() stubbed

There are three notable things to be observed in this output:

- The

libvfscorecomponent mounted a ramfs at/(timestamp0.108323). - The

libukcpiocomponent extracted all the files of the (embedded) initial ramdisk into this ramfs filesystem (from timestamp0.110719). - The

libukbootcomponent finally called the kernel’smain()function, namely the Nginx application, with the parameters passed on the command line (timestamp0.140582).

All of this within 150 milliseconds, on emulated hardware.

For comparison, the Micro VM that your current playground box is running in requires about 2 seconds just to reach the point where it can run its init process, and about half a second more for reaching the main user target:

sudo journalctl -b -o short-monotonic

[ 0.000000] docker-01 kernel: Linux version 5.10.246 (root@buildkitsandbox) ...

[ 0.000000] docker-01 kernel: Command line: panic=1 8250.nr_uarts=1 rw pci=off ...

...

[ 1.808932] docker-01 kernel: Run /sbin/init as init process

...

[ 2.459813] docker-01 systemd[1274]: Reached target default.target - Main User Target.

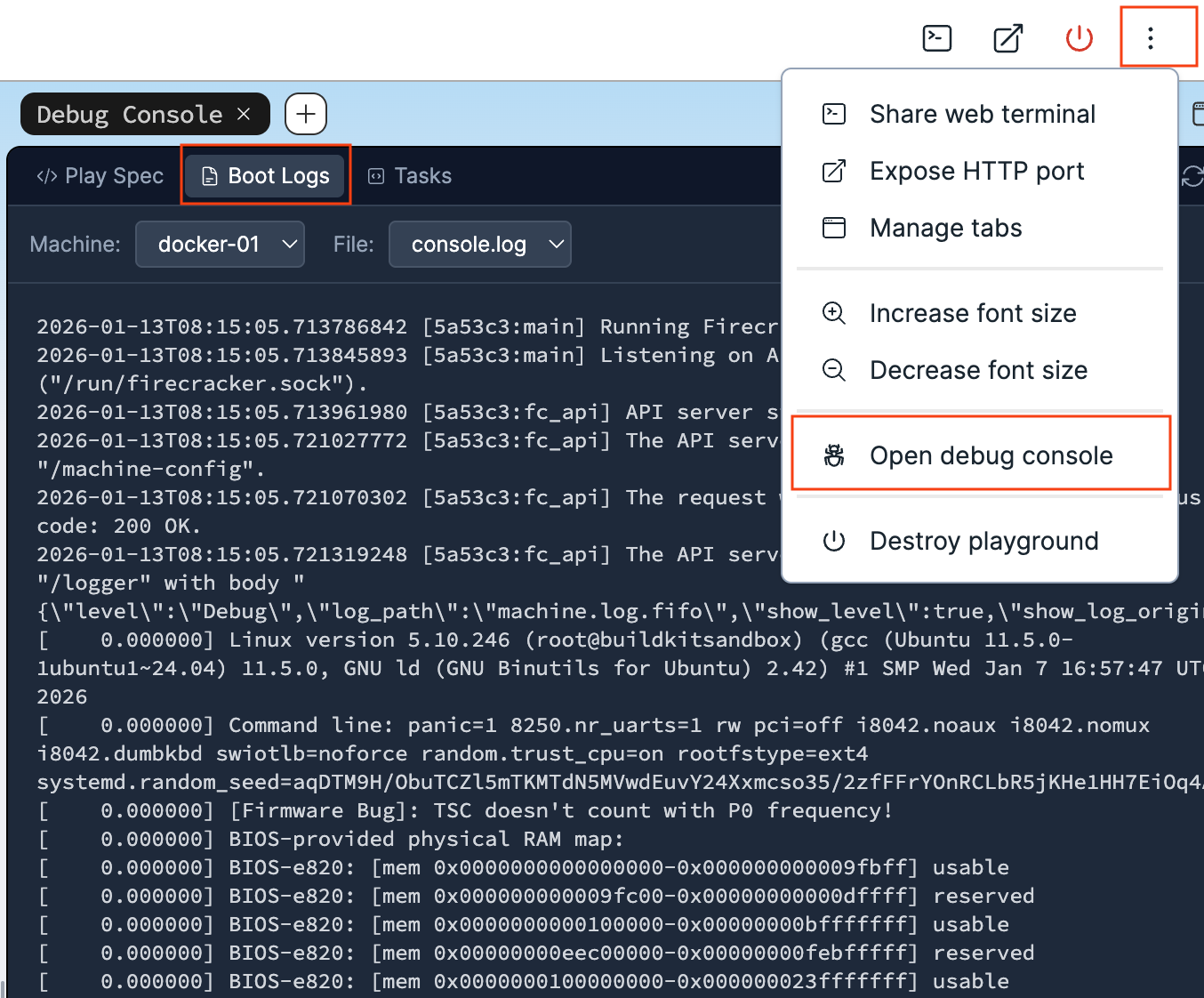

Console logs of the playground box

Take a look at the console logs of your playground Linux box and compare them with what you are currently seeing in your terminal :)

So, what else can we do with this unikernel at that point? Not much, at least not just yet. Since you did not create the virtual machine with any network device, you cannot perform any meaningful interaction with the Nginx server, such as sending a HTTP request to it. This aspect was deliberately left out from this section. The good news is that we are going to remediate to it in the next one.

For now, terminate the QEMU process by sending the key combination Ctrl+A followed by X on your keyboard.

QEMU: Terminated

In case this key sequence does not work for you, open a second terminal and interrupt the QEMU process from there:

sudo killall qemu-system-x86_64

As the BIOS sends control characters which tend to corrupt interactive terminals, consider resetting your terminal’s state now to avoid glitches when typing future commands:

reset

Docker Integration

By Docker, what we really mean here is software conforming to the OCI image and runtime specifications. But that didn’t make for a catchy heading.

Arguably, we could have covered a bit of the network configuration required for obtaining a HTTP response from Nginx in the previous section, and this tutorial could have ended here. Except that would have meant passing on some very interesting ways of running unikernels alongside Linux containers.

Containers are currently the dominant deployment unit in the cloud-native landscape. A rich ecosystem of technologies, rallied behind the Kubernetes12 project, allows virtually anyone to run services at "Google-scale" nowadays. Much of this convenience stems from the assumption that everything is packaged and run like a container.

Could unikernels, instead of competing against this ecosystem, tap into its richness to ease their adoption?

It turns out that this idea isn’t new. Several projects have shown that it is possible to run applications as if they were a container, but with the enhanced isolation of a virtual machine. Those are presented in the section Secure Container Runtimes of the post Journey From Containerization To Orchestration And Beyond.

In this section, you will use two open source projects listed on the page of the Unikernel Alliance:

- Bunny — to create an OCI image from your already built Nginx unikernel.

- urunc — to run the Nginx unikernel off its OCI image, this time with network support.

... all of this using nothing but the docker CLI.

Let’s get started.

OCI Image

Bunny makes packaging unikernels as easy as it is to package containers. The resulting images are standard OCI images that can be pushed to and pulled from any container registry.

First off, change your working directory to oci/, assuming that you are currently still in the nginx/ workspace:

cd oci

This directory contains a single file named bunnyfile with a YAML syntax.

cat bunnyfile

bunnyfile

#syntax=harbor.nbfc.io/nubificus/bunny:latest

version: v0.1

platforms:

framework: unikraft

version: 0.20.0

monitor: qemu

architecture: x86

kernel:

from: local

path: nginx_qemu-x86_64

cmd: ['-c', '/nginx/conf/nginx.conf']

You would be right to assume that a unikernel shall be packaged using instructions from a Dockerfile, like any other container image. However, because Bunny was designed to be used as a frontend for BuildKit13, it is able to parse its own build definition which is tailored for packaging the special software artifact which are unikernels.

In a bunnyfile, the generic and imperative instructions of a Dockerfile (ENV, COPY, RUN, etc.) are traded for declarative and structured attributes which describe the nature of the unikernel and how it should be run:

- The

frameworkit was built with (what type of unikernel). - The virtual machine

monitorthat can run it (what hypervisor). - The

cmd(command-line parameters) that should be supplied to the kernel at boot time. - The

pathat which the kernel image resides on the local filesystem.

The Dockerfile syntax is also supported by Bunny as an alternative to the bunnyfile syntax.

According to that last path instruction, Bunny expects the unikernel executable inside the current directory with the name nginx_qemu-x86_64, so you will need to copy it there:

cp ../workdir/build/nginx_qemu-x86_64 .

Run a Docker image build inside the current directory, using bunnyfile in place of the default Dockerfile, and see what happens:

docker image build \

-f bunnyfile \

-t lab/nginx-unikernel:latest \

.

[+] Building 6.0s (8/8) FINISHED docker:default

=> [internal] load build definition from bunnyfile 0.0s

=> => transferring dockerfile: 274B 0.0s

=> resolve image config for docker-image://harbor.nbfc.io/nubificus/bunny:la 1.4s

=> docker-image://harbor.nbfc.io/nubificus/bunny:latest@sha256:5c4ea3e06932d 3.9s

=> => resolve harbor.nbfc.io/nubificus/bunny:latest@sha256:5c4ea3e06932d2668 0.0s

=> => sha256:0e389784892b49cd4cd99ca91a80297d06961a154497f72 6.32MB / 6.32MB 3.7s

=> => extracting sha256:0e389784892b49cd4cd99ca91a80297d06961a15449f3efe7c0c 0.1s

=> Internal:Read-bunnyfile 0.0s

=> => transferring context: 274B 0.0s

=> local://context 0.0s

=> => transferring context: 2.01MB 0.0s

=> copy /nginx_qemu-x86_64 /.boot/kernel 0.0s

=> mkfile /urunc.json 0.0s

=> exporting to image 0.3s

=> => exporting layers 0.2s

=> => exporting manifest sha256:f32ca3bca1dd80259da2fdd4fbc1e4e31127f50d6e02 0.0s

=> => exporting config sha256:d6fee3cd090c49bcaea28735d783b410fe16519199a158 0.0s

=> => exporting attestation manifest sha256:6b208d4aab720d228a27adf0576d7050 0.0s

=> => exporting manifest list sha256:42e109d9ea5fba9c86de0296559468f13d3f2f7 0.0s

=> => naming to docker.io/lab/nginx-unikernel:latest 0.0s

=> => unpacking to docker.io/lab/nginx-unikernel:latest 0.0s

Even though bunny does not come pre-installed inside the playground box, the build completed without hurdle. Is this surprising? Upon closer inspection, it shouldn’t be.

Because the first line in the bunnyfile is a syntax directive with a special meaning, BuildKit was able to understand that it had to load the bunny frontend dynamically from a container image and invoke it to generate its build graph:

#syntax=harbor.nbfc.io/nubificus/bunny:latest

Neat!

The OCI images produced by Bunny have the peculiarity of being automatically labeled with some exotic key-values. You can enumerate these by inspecting the lab/nginx-unikernel:latest image you created:

docker image inspect \

--format='{{range $k,$v := .Config.Labels}}{{printf "%s=%s\n" $k $v}}{{end}}' \

lab/nginx-unikernel:latest

com.urunc.unikernel.binary=/.boot/kernel

com.urunc.unikernel.cmdline=-c /nginx/conf/nginx.conf

com.urunc.unikernel.hypervisor=qemu

com.urunc.unikernel.initrd=

com.urunc.unikernel.mountRootfs=false

com.urunc.unikernel.unikernelType=unikraft

com.urunc.unikernel.unikernelVersion=0.20.0

Without further ado, let’s figure out what makes those labels useful.

OCI Runtime

In order to create and run a container, the containerd container manager invokes a container runtime that prepares the containerized process to run within the desired namespaces and cgroups hierarchy. In the realm of Linux containers, the container runtime of reference is runc.

runc makes numerous assumptions about the way a container has to run:

- a Linux process

- on top of a shared kernel

- with standard I/O streams (stdin/stdout/stderr)

- isolated from other processes by namespaces

- with its resources constrained by the facilities of that shared kernel (cgroups)

A unikernel is different. As a virtual machine running under the management of a virtual machine manager:

- Its resource constraints are enforced by virtualized hardware, not just cgroups.

- The host’s namespaces do not propagate inside the guest, making namespaces such as

PID,Mount,UserandCgrouplargely irrelevant. - Bind mounts must be passed from the host through the hypervisor, in a form that is supported by the guest kernel.

- I/O streams of the guest application are not forwarded outside of the virtual machine.

For those reasons, spinning up a unikernel–or in fact any kind of virtual machine–from a container image requires a container runtime that is aware of those distinctions and is capable of operating around them.

That runtime is urunc.

In containerd, there is a naming convention that allows selecting a specific runtime for running a container without having to configure containerd to know about that runtime. By requesting a runtime named io.containerd.$(RUNTIME).v2 on the command line, containerd attempts to create the container through the shim executable containerd-shim-$(RUNTIME)-v2, if available in the PATH.

It turns out that the urunc shim executable installed on the playground box follows that naming convention:

ls -F1 /usr/local/bin/*urunc*

/usr/local/bin/containerd-shim-urunc-v2*

/usr/local/bin/urunc*

So all you need to do in order to pick urunc for running your Nginx unikernel image is specify that runtime name as an argument to docker container run. We also set its name explicitly to unikernel to facilitate future docker commands:

docker container run \

-d --rm \

--name unikernel \

--runtime io.containerd.urunc.v2 \

lab/nginx-unikernel:latest

e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0

Default runtime

When the --runtime flag is not specified in docker container run commands, containerd chooses the runtime based on its own default. In a vanilla containerd distribution, this default is runc:

containerd config default

config.toml

[plugins.'io.containerd.cri.v1.runtime']

#...

[plugins.'io.containerd.cri.v1.runtime'.containerd]

default_runtime_name = 'runc'

#...

[plugins.'io.containerd.cri.v1.runtime'.containerd.runtimes]

[plugins.'io.containerd.cri.v1.runtime'.containerd.runtimes.runc]

runtime_type = 'io.containerd.runc.v2'

Verify that the unikernel is running (as a container):

docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

e2348010d439 lab/nginx-unikernel:latest "-c /nginx/conf/ngin…" 10 seconds ago Up 10 seconds unikernel

Then print its logs (console output):

docker container logs unikernel

...

Powered by

o. .o _ _ __ _

Oo Oo ___ (_) | __ __ __ _ ' _) :_

oO oO ' _ `| | |/ / _)' _` | |_| _)

oOo oOO| | | | | (| | | (_) | _) :_

OoOoO ._, ._:_:_,\_._, .__,_:_, \___)

Kiviuq 0.20.0~07044e69

[ 0.131892] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 472> Pre-init table at 0x2d11e8 - 0x2d11e8

[ 0.132060] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 483> Constructor table at 0x2d11e8 - 0x2d11e8

[ 0.132218] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 498> Environment variables:

[ 0.132344] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 500> PATH=/bin

[ 0.132467] Info: [libukboot] <boot.c @ 506> Calling main(3, ['/.boot/kernel', '-c', '/nginx/conf/nginx.conf'])

[ 0.153510] Warn: [libposix_process] <rt_sigprocmask.c @ 72> __uk_syscall_r_rt_sigprocmask() stubbed

[ 0.153760] Warn: [libposix_process] <rt_sigaction.c @ 69> __uk_syscall_r_rt_sigaction() stubbed

The output is more or less identical to the one shown when you ran the unikernel via QEMU earlier.

As the BIOS sends control characters which tend to corrupt interactive terminals, consider resetting your terminal’s state now to avoid glitches when typing future commands:

reset

It doesn’t end here. Check the IP address assigned to the container:

docker container inspect \

--format='{{.NetworkSettings.Networks.bridge.IPAddress}}' \

unikernel

172.17.0.2

Then send a HTTP request to that IP address using curl:

curl -D- http://172.17.0.2

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.15.6

Date: Fri, 01 Jan 2026 00:00:00 GMT

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 139

Last-Modified: Fri, 01 Jan 2026 00:00:00 GMT

Connection: keep-alive

ETag: "69611cbd-83"

Accept-Ranges: bytes

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello from iximiuz Labs!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello from iximiuz Labs!</h1>

</body>

</html>

This time around, networking is fully functional, and it appears to be working just like with a container!

That is great progress compared to what you ended up with at the end of the previous section. Not only interacting with the application running inside the guest is now a reality, but reaching that state was remarkably easy; you did not need to use anything but docker commands, or even make adjustments to your unikernel.

Understanding the Unikernel Container

We are now going to dissect what just happened in order to understand how making the unikernel feel like we are interacting with a Linux container is even possible.

As explained earlier in this tutorial, iximiuz Labs playgrounds do not support KVM. During its initialization, your playground box built and installed a patched version of urunc which omits certain problematic QEMU CLI flags such as -enable-kvm.

Process Tree

If you look at the processes currently running in your playground box, you should see a process with a familiar command line at the bottom of the list:

ps axjfww

PPID PID PGID ... COMMAND

1 23927 23927 ... /usr/local/bin/containerd-shim-urunc-v2 -namespace moby -id e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0 -address /run/containerd/containerd.sock

23927 23951 23951 ... \_ /usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 -m 268M -L /usr/share/qemu -nographic -vga none -smp 1 --sandbox on,obsolete=deny,elevateprivileges=deny,spawn=deny,resourcecontrol=deny -kernel /.boot/kernel -net nic,model=virtio,macaddr=6e:e5:40:9d:22:87 -net tap,script=no,downscript=no,ifname=tap0_urunc -append Unikraft env.vars=[ PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin HOSTNAME=e2348010d439 ] netdev.ip=172.17.0.2/24:172.17.0.1:8.8.8.8 -- -c /nginx/conf/nginx.conf

That’s right, a QEMU process, parented to the urunc container shim, with arguments that look very similar to the ones you passed on the command line to create the virtual machine manually in the previous section of this tutorial.

Remember those somewhat exotic labels set on the container image? You just found the usage of two of them:

com.urunc.unikernel.hypervisor=qemu

com.urunc.unikernel.cmdline=-c /nginx/conf/nginx.conf

This parenting of qemu-system-x86_64 to the container shim is the reason why docker container logs printed the standard output (stdout) of the QEMU process, namely the virtual machine’s console output.

Intermediate process tree

If you manage to list the processes fast enough while the container is still being created, you will notice that the process with the container’s PID was originally a urunc process (not to be mistaken for a urunc shim process):

ps axjfww

PPID PID PGID ... COMMAND

1 23927 23927 ... /usr/local/bin/containerd-shim-urunc-v2 -namespace moby -id e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0 -address /run/containerd/containerd.sock

23927 23951 23951 ... \_ urunc --root /run/containerd/runc/moby --log /run/containerd/io.containerd.runtime.v2.task/moby/e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0/log.json --log-format json create --bundle /run/containerd/io.containerd.runtime.v2.task/moby/e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0 --pid-file /run/containerd/io.containerd.runtime.v2.task/moby/e2348010d439f4f8197d1d706b2f99fbeebab76595e8320478057f7c48fc2da0/init.pid e234801