In Poland, a ghost hunter warns that the spirits might go on strike: they’re angry that we believe in them less and less. In Australia, an ornithologist is trying to prove the existence of a bird species that whistles popular songs from the 1920s. Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, scientists are speculating that we might live inside a computer simulation.

You wouldn’t believe what people are up to.

The writer and comedian Dan Schreiber — like an anthropologist of crazy ideas — dedicates himself to compiling these cases, which, in fact, seem t…

In Poland, a ghost hunter warns that the spirits might go on strike: they’re angry that we believe in them less and less. In Australia, an ornithologist is trying to prove the existence of a bird species that whistles popular songs from the 1920s. Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, scientists are speculating that we might live inside a computer simulation.

You wouldn’t believe what people are up to.

The writer and comedian Dan Schreiber — like an anthropologist of crazy ideas — dedicates himself to compiling these cases, which, in fact, seem to haunt him. The 41-year-old has a friend who demanded that Schreiber confess that he’s an actor and that his life is a simulation, like The Truman Show. He’s met someone who claims to be half-reptilian, as well as another person who claims to have seen the Virgin Mary at the foot of her bed. This last person is his own partner, Fenella. Schreiber maintains that we’re all a little crazy.

“There are many mysteries in the world and many people are convinced they’ve solved them,” the comedian notes, via video conference from London. “They dedicate their lives to defending what they believe to be true. And that makes world history much funnier and stranger than it seems.” To illustrate this, he wrote The Theory of Everything Else: A Voyage Into the World of the Weird (2022), where he explores the strangest aspects of human thought.

As an example, he explains, we talk a lot about Charles Darwin, his voyage on the HMS Beagle, the fantastic idea of natural selection and the evolution of species. “What we don’t know is that Darwin was almost not allowed on the ship… because Captain FitzRoy didn’t like the shape of his nose!” There’s an explanation for this: it was the era of phrenology, the pseudoscience that believed cranial structures revealed a lot about individuals.

Schreiber likes unusual stories, and his is certainly anything but conventional. His parents were hairdressers (his father Australian, his mother British) who fell in love in Hong Kong. They opened a Western-style salon and dedicated themselves to styling the hair of celebrities. “They worked with expats; the Chinese weren’t particularly interested in having their hair styled by Westerners,” he explains. But then, Madonna’s fame exploded in Hong Kong, and suddenly, all the women wanted that kind of hairstyle. And so, Schreiber and his siblings were born in the city, all because of Madonna’s hairstyle.

They moved to Sydney, Australia, when he was 13. But his childhood in Hong Kong was a major influence: “That city was a melting pot of cultures: when I went to friends’ houses for dinner, they were Indian, or Chinese, or Canadian families… I was exposed to a very diverse set of beliefs.” After finishing high school, he moved to the U.K. (where he still lives), working as a television writer on the BBC program QI — which stands for “Quite Interesting” — and hosting podcasts such as The Museum of Curiosity and No Such Thing as a Fish.

He has found (or rather, he claims, they’ve presented themselves to him unexpectedly) some very strange things: in 1970, the Philips record label released the album A Musical Seance. Compiled by Rosemary Brown, a former London cook, it contained previously unreleased pieces by Liszt, Chopin, Beethoven, Brahms and Debussy. Brown had gained access to them in a curious way: she made mental contact with the deceased composers, who had dictated the scores exclusively to her.

Another fascinating character is Kary Mullis, the U.S. biochemist who developed the PCR test and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for it (he died in 2019, shortly before we all became familiar with his invention). Despite making such an important contribution to science and human health, Mullis was an eccentric character who claimed to have seen a glowing raccoon in the night (who spoke to him) and denied the existence of HIV. Interestingly, Luc Montagnier — who won the Nobel Prize for identifying HIV — became a fervent anti-vaccine activist. He also believed in the “water memory” theory and recommended eating papaya to treat Parkinson’s disease.

In his book, Schreiber uses these figures to criticize what he calls “Nobelitis,” or the proliferation of experts whom we blindly believe simply because they have a Nobel Prize. Schreiber is fascinated by these brilliant minds, who, while dominating their disciplines, are also completely eccentric. For example, the great physicist Wolfgang Pauli was fascinated by the number 137 and saw it everywhere. Other Nobel laureates — such as Linus Pauling and William Shockley — defended eugenics. And he’s not just talking about Nobel Prize winners: tennis champion Novak Djokovic — also famous as a vaccine denier and believer in strange theories about diet — thinks that a bad mood can be transmitted to food, destroying its nutritional properties. You have to eat when you’re happy!

There are people who take advantage of strange theories to make a profit. For example, in Shingo, an island in Japan, they claim that Jesus Christ died there, after crossing Alaska and Siberia. On the island, locals have even built a lucrative business around his hypothetical tomb. And it isn’t the only town that has managed to bolster its existence with the strange. There’s Loch Ness, Scotland, where the famous (and never seen) monster brings in profits; there are the islands of the infamous Bermuda Triangle; and, of course, there are the wooded villages where (so they say) Bigfoot has been sighted.

“One of the best things anyone can say to you is, ‘Your house is haunted!’” Schreiber exclaims. He’s talking about that old English house in Pontefract, where the ghost of the Black Monk lives: people go there to spend the night, they get terrified… and then, they post fantastic reviews online. “Once, an exorcist came, ready to banish the ghost. But the owner got furious: that monk was his livelihood!” the author chuckles. Perhaps he should put up a sign saying “No Exorcisms.”

Strange theories are great fun. However, as the writer points out, they should be taken with a grain of salt: he warns that none of it is real. And, as with the case of anti-vaxxers, these myths can be dangerous. Especially since we’re living through a global offensive against scientific knowledge, fueled by the Trump administration. “I want to go back to a time when telling ghost stories around the campfire, [or] marveling at a conspiracy theory about Kennedy’s death, was controlled. When this was innocent and not used as a weapon. When the story itself was what mattered,” the writer sighs, referring to the polarization caused by widespread misinformation.

Today, he says, we live amidst a crisis of confidence, fueled by a thirst for “global gossip.”

“People like to tell each other stories about what scientists or leaders are doing, just like how they tell each other stories about the other parents at school,” he details. And many people with unusual beliefs seek to overcome loneliness and individualism. They wish to belong to something bigger, to a community, through those beliefs: this is seen in the case of flat-Earthers. “It’s like someone who is religious — not so much for the beliefs themselves — but rather so that they can go to church on Sundays, socialize and have someone to ask for help,” the writer explains.

Ultimately, one could say that part of the world’s problems stem from the fact that we’ve lost our sense of humor and have taken ourselves – even our own beliefs – too seriously. “I think that, after music, humor is humanity’s greatest invention,” Schreiber affirms. “With a joke, you can make someone feel better; laughter generates endorphins. That’s why there’s a British comedian who says that comedians are like drug dealers of a drug that makes you feel great through the magic of words.”

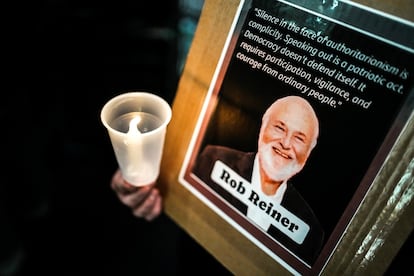

This is why, according to the author, many people took Trump’s comments about the death of director Rob Reiner badly, or why so many mourned Robin Williams’ death: “They brought so much happiness to the world.”

Speaking of the U.S. president: does Schreiber find Trump funny? “Yes!” he replies. “Many people refuse to accept it, because they think that this implies that he’s a good guy. But part of the Trump problem is that he’s funny... even though he can’t laugh at himself,” the author concludes.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition