Nobody who has watched Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) can ever forget the boy at the beginning of the film: he is sitting up on a bed, running his hand across a surface, which may or may not be a screen. On that surface emerges the indistinct face of a woman (perhaps Bibi Andersson?), which gazes hauntingly at us. Then a bright spasm of light dissolves it.

When the film credits are about to roll, the same shot returns – and the boy keeps running his hand over the screen.

Twilit reimaginations

The poems in Jennifer Robertson’s debut collection of poetry, Folie à Deux, are just like that: microscopic attempts to get at a world beyond the ordinary…

Nobody who has watched Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) can ever forget the boy at the beginning of the film: he is sitting up on a bed, running his hand across a surface, which may or may not be a screen. On that surface emerges the indistinct face of a woman (perhaps Bibi Andersson?), which gazes hauntingly at us. Then a bright spasm of light dissolves it.

When the film credits are about to roll, the same shot returns – and the boy keeps running his hand over the screen.

Twilit reimaginations

The poems in Jennifer Robertson’s debut collection of poetry, Folie à Deux, are just like that: microscopic attempts to get at a world beyond the ordinary, to peel the surface of language and discover the shadowy undercurrents beneath it. In a voice that comes across as both intimate and intrepid, Robertson crafts a poetic persona that recalls tenderness, yet is unafraid to perform incisions. Here are poems that are battle scars, twilit reimaginations of the what-might-have-been, poems that peck hard at the surface of our language, and poems which offer a startlingly wry portrait of life before and after the internet age.

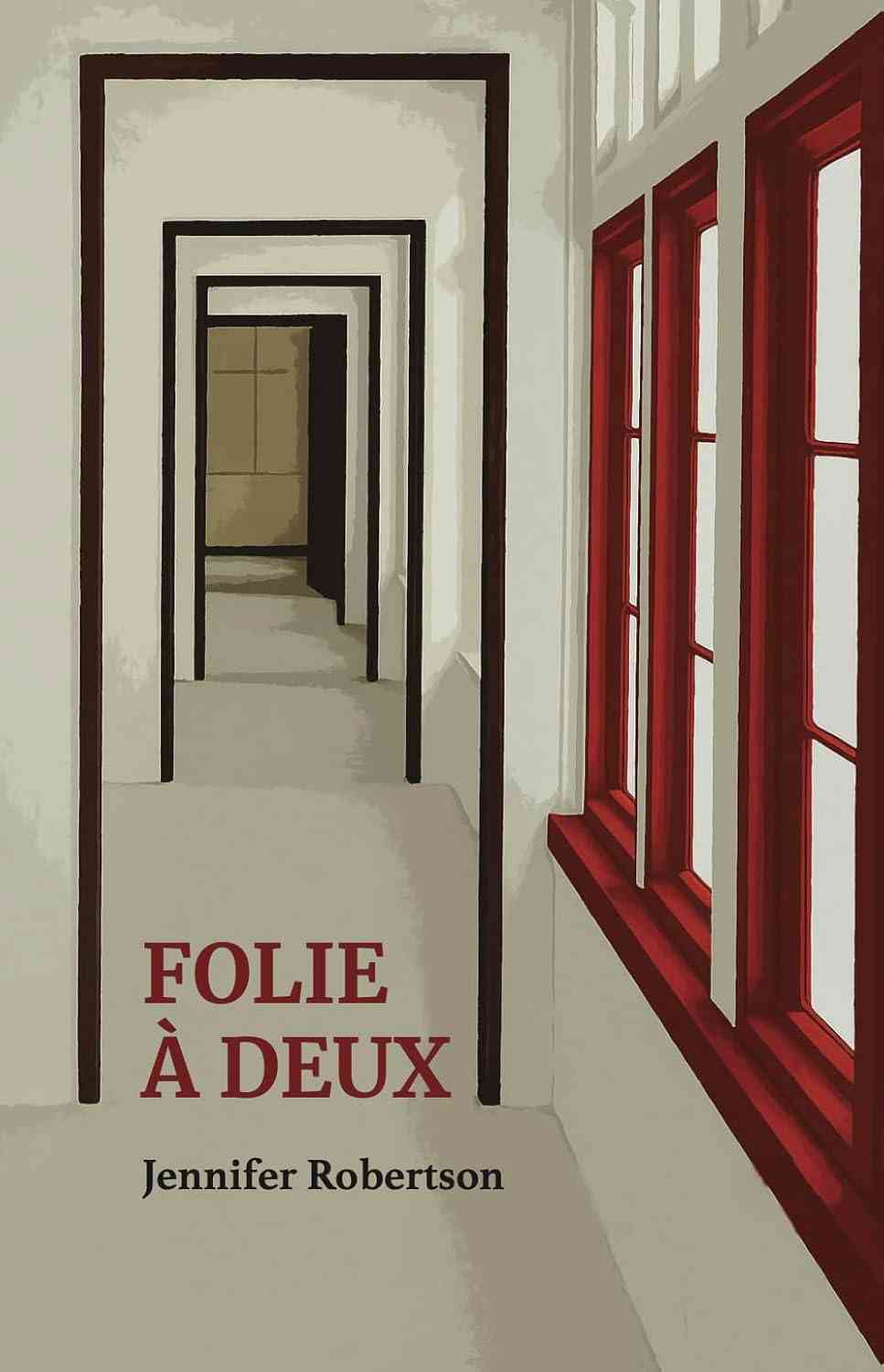

*Folie à Deux *is divided into five sections (or “acts”) – “The Latch-Key Girl”, “Because We Spoke Like Bees Do”, “To Kiss Like Caravaggio”, “The Final Finding of the Sea”, and “The Locus Amoenus” – which take the reader on a journey both sublime and surrealistic. In many ways, it is like going through a museum of mise en abyme: within each picture is a copy of itself, creating an endlessly referential loop. This effect is amply testified by the book’s cover image – designed by the Paperwall team after a photograph by Nimisha Pixie – which depicts a similar series of rooms within a room. This instantly situates the reader within the topography of the poems, which have “two doors and no exit”.

Reading the first section, “The Latch-Key Girl”, is a little like going through an old photo album: this is the world of Lambretta rides and mixtape music, of growing up home alone without the aid of smartphones or grandparents. Yet Robertson evokes this now-vanished world with a dispassionate tenderness that can often seem cynical – such as the frighteningly sharp ending to “Pots, Pans, and Petals”:

“Beep, beep, beep I wonder if that is my conscience or the microwave”

And yet, there is also a sense of wistful tugging at memory, as in that stunningly short elegy, “We Grew up in Places that are Gone”:

“Why do we look for sutures and siblings

in all the wrong places when Google gives us

22,950,000,000 results for the word home?”

Poems like these cleave through what Kafka calls “the frozen sea within us”, managing to express the seemingly inexpressible. It is as if Robertson is engaged on a quest for articulation, and every medium – be it cinema, music or writing – is patiently turned over and examined for the possibilities it inspires. This could come in the form of playful little interventions, such as the moment in “The Relevance of Assorted Wikipedia Lines”, in which she states, “Sometimes, you need eyes to hear some noise”.

In yet another poem, she writes, “Not everything is citable. What is silence, if not a discretion of turning the pillow over?” Ordinary fragments of activity like these take on a renewed significance. Likewise, sounds and other symbols develop a recurring pattern of their own – such as the palpatory motion “lub-dub, lub-dub”, or “the ruined number, seventeen”. As the reader grows to identify with these symbols, others begin to appear – sometimes from history, sometimes from literature. At one point, Ezra Pound’s famous injunction “Make it new” resurfaces as an Instagram idea:

“Make it new. Repost. The panoply of ideas.”

Parallel to this wry sendup of modernism and technology is also a strong streak of identification with female figures in history. We are pleasantly surprised to find Mrs Dalloway walking away at the end of a poem, or Emily Dickinson discreetly dotting the corners of another. Later, the poem dedicated to Clara Schumann is another masterpiece of conjuration, which appears to give voice to the congeries of images that flit through our mind while listening to music. Many of the poems thus act not just as explorations of a personal dreamscape, but also as footnotes to historical figures, reclaiming and revivifying their artistic achievements. And in doing so, Robertson places herself in a long ancestry of feminine writing dating back to Sappho.

Between interstices

One of the major highlights of the collection is the section called “To Kiss Like Caravaggio”. Like the famous epigraph from EM Forster’s novel Howards End (1910). “Only connect”, the poems here imagine various kinds of contact and connection. A man walks “like a monologue”, and “pauses like the word saudade”; or “a sentence tastes red”, before tasting “like a ruined number, seventeen”. Sight and sound are mingled together in one synaesthetic bundle, as memory leads on to memory, and develops a logic of its own. It is not long before the reader is reminded of another comparison, perhaps an experience that everyone undergoes at some point in their childhood: sitting in a stationary train, and seeing the neighbouring train begin to move. Where, we wonder, does the movement come from? From within or without? Or both?

In a way, the poems are an attempt to answer just that; many of them take place in that small interstice between wondering which train is moving, and finding out that it isn’t one’s own. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that even this little experience is charted by Robertson in a poem called “All Maps are Tactile”.

Movement, we soon realise, is central to this collection; the poems move like human feet, and ascend and descend like a Chopin piece. The movements can take any form – the syllables of a word, the motion of a person’s legs, a face crumpling into tears, or even a civilisation hastening towards its decline. In between the utterance of a word and the running of a gazelle, we learn, there is no difference. A particularly poignant piece is “The Tiny Economies of Restraint”, where the poet prefers not knowing to knowing: “I like not knowing your coldness/or the length of your shadow/or the haunted architecture of your face”. Rather, she says, “I like the tiny economies of restraint/of not knowing the size of your fist/when the doorbell rings”. Because anticipation is part of intimacy.

Other such gems crop up throughout the collection. Unwittingly, perhaps, Robertson ends up completing what Forster left unsaid: “Only connect, and everything will make sense”.

Variations on tactility

“Tactility” is another important element in the poems. Like the morbidly curious boy in Persona, Robertson’s poetry seems to be straining hard to break through the artifices of daily life. Yet poetry is not cinema, and the pen does not possess the restless agility of the camera; instead, throughout this collection, it offers us tantalising glimpses of this world beyond the curtain. These could come in the form of the “evenings (that) arrive as toddlers”, or the “untamed grief (that) often turns feral, runs wild/Becomes a gazelle”. As words turn into images, connotations get blurred, and new patterns of association emerge. Language, in Robertson’s hands, keeps getting denuded and reconfigured; at no point in time is it constant and quiescent. On occasions, it merely becomes a tenant in the brain’s imagination; tamed to the point of servility, it yields to the kind of brilliant simplicity which is evident at the beginning of “X-Ray”:

“One doesn’t discover loneliness suddenly, like an experiment”

It ends with a noirish imagery in which bones “show up as white” and “the air in your lungs/shows up as black”. In one fell swoop, the loneliness of the individual becomes a collective, urban disease, which is inhaled and exhaled daily like cigarette smoke; more than two centuries ago, the famous English critic Samuel Johnson would have decried this kind of comparison as “yoked by violence together”. Yet today, we know better – after all, we have come to inhabit such metaphors in the cities we have built.

Elsewhere, language wriggles haplessly in the hand like an earthworm out of its hole. Indeed, many of the poems seem to have an air of having forced language out of its burrowing place, and we, the readers, become privy to this process of excavation. Much of this may have to do with Robertson’s familiarity with another kind of excavation, that of the human body – her father was an anatomy professor – and this lends it a quaintly surreal quality. As bones and osseous material start invading the poems, we realise that the poet, like an expert anatomist, is trying to get at the “skull beneath the skin” (as TS Eliot once put it). This fascination with the structural part of language is borne in the tellingly titled “What I Write About When I Write About Bones”:

“There’s nothing sexier than a well-written sentence. I love to watch the tension between phrases; an ill-fitted, rank outsider word getting acclimatised: the cutting, the pruning, the economy of slitting a word bare; the descent into pithiness, the elevation into a body of leanness. The sheer vanity of sentence creation is nothing short of spectacular love-making”.

In the last section, “The Locus Amoenus”, everything comes full circle – it is like an indulgent, retrospective glance at the whole collection, surprising us with its ability to lull the reader into the poet’s workshop. “Poetry was surprise and magic”, writes Robertson, “akin to finding a broadsheet with/Sappho’s fragments on a subway”. As we climb deeper into the labyrinth, we suddenly begin to encounter familiar objects and sensations– until we realise that we are face to face with the poetic persona itself. In its original Latin connotation, locus amoenus refers to a sort of pleasant spot or retreat; and sure enough, this section is where we can find the poet at her calmest: in the act of creation.

It is also here that the book’s epigraph – “Break cover, rebel heart/And speak”, from Ranjit Hoskote’s poem “Diagnosis” (collected in Vanishing Acts) – at last finds full resonance. While the act of articulation can become a vehicle for disrupting monolithic histories, it also marks a decisive moment in the individual consciousness: it is a step towards achieving a fuller personhood, and a step away from a passive, Bartleby-like fate. Folie à Deux thus becomes a remarkable vessel of self-expression, managing to comb through personal history with a clinical finesse, while at the same time providing expression to some of the deepest ironies of our age.

Aditya Shiledar is a writer and researcher whose works have previously appeared in The Hitavada and NCPA’s ON Stage*, among others.*

**Folie à Deux, Jennifer Robertson, Paperwall Publishing.

- We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in. *

Get the app