Flawed scientific articles don’t just clutter journals — they misguide policies, waste taxpayer funds, and endanger lives. Errors in top-tier research persist due to a broken correction system. Consider our own recent experiences.

In March 2025, Communications Earth & Environment published a paper claiming oil palm certification reduces yields and drives land expansion. But the study misread satellite data – interpreting temporary declines during replanting as a loss of production area. When corrected, the data show no decline in efficiency.

The paper’s conclusion, that certification increases land demand, is therefore unsupported. Despite this, our request for retraction was declined, and we were asked to submit a rebuttal t…

Flawed scientific articles don’t just clutter journals — they misguide policies, waste taxpayer funds, and endanger lives. Errors in top-tier research persist due to a broken correction system. Consider our own recent experiences.

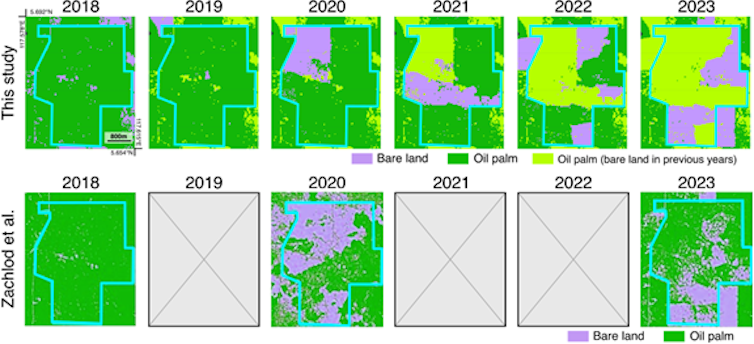

In March 2025, Communications Earth & Environment published a paper claiming oil palm certification reduces yields and drives land expansion. But the study misread satellite data – interpreting temporary declines during replanting as a loss of production area. When corrected, the data show no decline in efficiency.

The paper’s conclusion, that certification increases land demand, is therefore unsupported. Despite this, our request for retraction was declined, and we were asked to submit a rebuttal text, but our rebuttal remains under review nearly a year later.

Land-cover classifications compared. The original study (bottom) misidentified bare land (purple) as lost to palm oil production, while our reanalysis (top) shows this as replanting (light green) and continued palm oil production.

Another example is a 2023 Nature paper estimating deforestation due to rubber plantations. The study’s sampling errors overstated rubber’s deforestation footprint. Our correction finally appeared almost two years later – behind a paywall – by which time the flawed study had been cited 98 times and shaped multiple policy reports.

Both papers passed peer review in leading journals, showing that even top-tier systems promote errors as easily as insights.

Why errors are hard to fix

These cases, and too many more, show that academia’s “correction machinery” is faltering. Few journals prioritise retractions or errata, and researchers who expose errors receive little encouragement.

The academic economy rewards novelty over accuracy. Careers hinge on new papers, not careful corrections. Post-publication critique counts for little. Admitting error risks reputation. Pointing out others’ mistakes risks backlash.

In this context, it is unsurprising that errors – even those that are flagged – accumulate. Retractions are rare, slow, and often buried. One Nature paper was retracted 22 years later – after nearly 4,500 citations.

These delays carry costs. In medicine, flawed data have led to harmful clinical decisions – as seen in the now-retracted 2020 Lancet hydroxychloroquine study that briefly halted global COVID-19 trials.

In conservation, satellite-based deforestation estimates often vary widely, confusing policymakers and undermining trust in the evidence. Different studies have produced very different pictures of forest loss, leading to contested claims and uncertain priorities.

- ** Read more: ‘Publish or perish’ evolutionary pressures shape scientific publishing, for better and worse ** *

How we got here

The reasons are structural and self-reinforcing – driven by profit and pressure.

- Commercialisation of academic publishing

Many others have highlighted the problems of a system where the norm is that scientists, often funded by public money, conduct research, review papers for free, and then their institutions pay exorbitant fees to access the results while private companies pocket the profits.

The roots of this dysfunction trace back to Robert Maxwell, who in the 1960s turned Pergamon Press into a “perpetual financing machine”. Maxwell pioneered a model that commodified academic prestige and researcher vanity, creating the commercial empires that dominate the landscape today.

Maxwell’s model remains successful. Springer Nature reported profit margins of around 28% on nearly €2 billion (US$2.3 billion) in annual revenue. Elsevier and Wiley post even higher profit margins.

The website of Wiley, one of the global publishing giants posting high operating margins. shutterstock

Academic publishing is now one of the most lucrative industries per unit of input, but profitability rests on extensive unpaid academic labour – peer review alone totals more than 100 million hours annually – and on restricted public access to the outputs.

- ** Read more: Academic publishing is a multibillion-dollar industry. It’s not always good for science ** *

- Peer review and inequality of access

Peer review, the gatekeeper of scientific integrity, is buckling under an insatiable demand. The number of submissions is growing as many nations accelerate their scientific outputs, and AI tools facilitate the production of increasingly credible looking submissions. Nature itself recently described a “peer-review crisis”.

Retractions exceeded 10,000 in 2023 and continue to rise. Arguably, not a sign of self-correction working, but of quality control in crisis.

Meanwhile, paywalls and charges for open access publishing (APCs) exclude many of the researchers able to catch flaws. Nature’s APCs now reach €10,690 (US$12,690). These costs are effectively barring many from low-income countries from publishing, accessing or correcting published work.

Double income for the publishers: Researchers pay to publish. Readers pay to read.

Science, at least in theory, is self-correcting. But a system prioritising profit and prestige corrects only when it must – and slowly.

It’s time to reform

Science advances not by being right, but by discovering where it’s wrong – and fixing it. Systemic reform must reframe prompt correction as a hallmark of integrity, not a badge of failure.

Open correction platforms, shared data, and AI-assisted review tools already make rapid, collective scrutiny possible. What’s missing are the incentives and the courage to make that the new norm.

If publishers can profit from paywalled errors, they can afford open corrections. If institutions and funders can count our papers and citations, they can also count our corrections.

Open Access Publishing at least ensures that anyone can access and, therefore, correct science. shutterstock

Journals should make corrections visible, prestigious, and citable, and expand “Diamond Open Access” models. Wider access means more scrutiny and faster fixes.

Institutions should reward transparency over output, funders should back post-publication verification, and researchers should favour publishers that value rigour over hype.

You can encourage your university to join cOAlition S to advance fairer, faster correction. Readers, too, can help – by checking Retraction Watch before citing.

The tools for faster, fairer correction already exist – what’s missing is the will to use them. Errors are inevitable – but resigned silence isn’t. Science’s strength lies not in never being wrong, but in how effectively and openly it corrects itself.