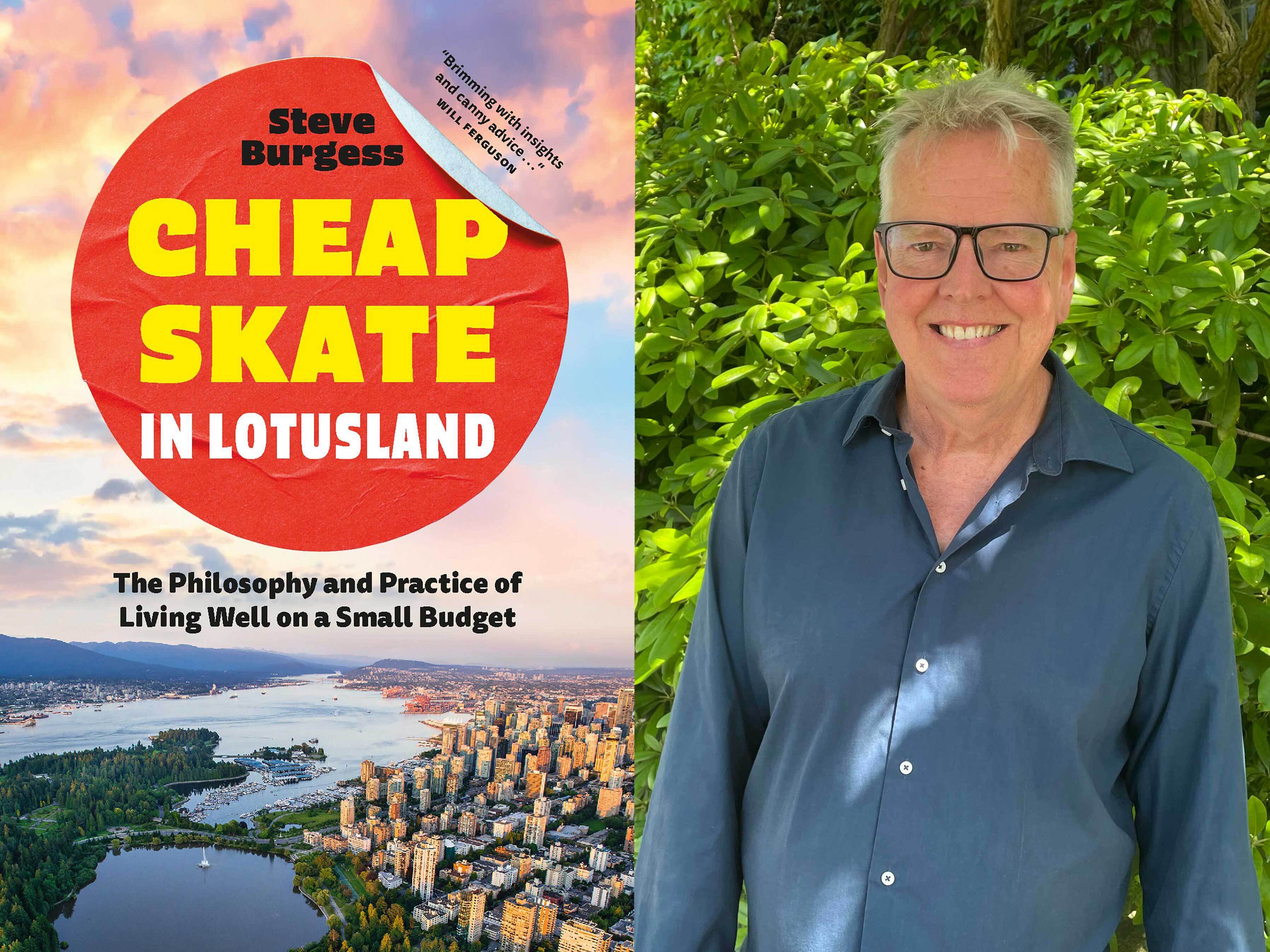

[Editor’s note: Tyee contributing editor Steve Burgess’s latest book dives into the philosophy and practice of frugality. A blend of memoir and reportage, ‘Cheapskate in Lotusland: The Philosophy and Practice of Living Well on a Small Budget’ is out through Douglas & McIntyre in the new year and considers what it means to live modestly but happily in Vancouver, an expensive city. In this excerpt from ‘Chapter Two: Eye of the Owl,’ Burgess takes us along on one of his favourite weekly pastimes: grocery shopping.]

It’s a Thursday evening at the No Frills supermarket in Denman Place Mall in Vancouver’s West End: a landscape of shelves and display cases, people strollin…

[Editor’s note: Tyee contributing editor Steve Burgess’s latest book dives into the philosophy and practice of frugality. A blend of memoir and reportage, ‘Cheapskate in Lotusland: The Philosophy and Practice of Living Well on a Small Budget’ is out through Douglas & McIntyre in the new year and considers what it means to live modestly but happily in Vancouver, an expensive city. In this excerpt from ‘Chapter Two: Eye of the Owl,’ Burgess takes us along on one of his favourite weekly pastimes: grocery shopping.]

It’s a Thursday evening at the No Frills supermarket in Denman Place Mall in Vancouver’s West End: a landscape of shelves and display cases, people strolling through a towering forest of consumer goods.

Gliding through the fluorescent light, I am an owl, a remorseless raptor in search of prey. In the corner of my vision, a red sticker. Silently I wheel about. The unsuspecting container of discounted spinach is doomed.

Grocery trips are highlights of my week. Does that sound sad? It shouldn’t. I love grocery shopping.

It’s a favourite activity even when I am abroad — a foreign supermarket can be especially fascinating, a window into a different culture. Here at home, supermarkets are easily taken for granted. But they are wonderlands, veritable El Dorados of sustenance as well as monuments to the staggering extravagance available to the 21st-century consumer. The capitalist marketplace, red in tooth and claw, is on display every day in retail arenas around the city. Proper navigation of these venues requires skill and a wary eye.

Wednesday is always a big day — that’s when the new flyers are posted online. Denman Street, the main shopping drag two blocks from my apartment, has both the No Frills and a Safeway. When their preview flyers go up one day ahead of their Thursday activation, I read them as avidly as brokers read stock tickers. I am looking for outliers, the really good deals on items that are my pantry staples.

I do not go to the store with a list or a budget. For me, making a budget would be equivalent to writing “Do not leap into traffic” on my shoes. Budgets are a means of restraint — necessary only if one is straining to get off the leash. Not me. I am always on the prowl for discounts, and with the exception of a few staples like milk and eggs, if I cannot get the item at a reduced price, I will do without for the time being. I enjoy a good hamburger, but it’s not a requirement for my personal happiness.

Lately, flyers have offered fewer bargains and are frequently padded with regular-priced items. The relative paucity of flyer discounts makes the actual shopping trip all the more crucial.

Most of the best deals now are spot discounts, individual store clearances not listed in national flyers and, most important of all, the red-sticker discounts on expiring meat and produce. Those items call for a shift to owl mode. Alas, I cannot turn my head 270 degrees like my avian role models. But unlike owls, I have eyes that can move in their sockets, which is just as good.

Look out, world. Tyee contributing editor Steve Burgess is shifting into owl mode for his new book, Cheapskate in Lotusland: The Philosophy and Practice of Living Well on a Small Budget.

Look out, world. Tyee contributing editor Steve Burgess is shifting into owl mode for his new book, Cheapskate in Lotusland: The Philosophy and Practice of Living Well on a Small Budget.

‘Every supermarket trip has a mission’

As I try to game the shopping trip to my own advantage, the supermarket is simultaneously attempting to manipulate me into irrational expenditure. Grocery shopping can be a battle of wits.

Dr. Jordan LeBel of Concordia University has spent many years studying supermarket retail techniques. He says every step you or I take in the store has been analyzed.

“Each major supermarket has a distinctive ‘planogram,’ how they’re going to lay things out,” LeBel says. “The way you go through the store is carefully studied.”

LeBel says the prevailing strategies have changed over time. “Years ago — and there are still some supermarkets that fall into this category — the first food section you’d see coming in would be fresh fruits and vegetables. The thinking at the time was, people see this when they come in, it’s colourful, it smells nice, it puts them in a good mood. Then they fill up the basket with fresh fruits and vegetables, which gives them a good conscience. So that when they turn the corner and end up in baked goods, the cookie aisle, they think, ‘Oh, well, I bought all these fruits and vegetables. I can grab the Oreo Double Creme,’ or whatever.”

That strategy no longer dominates, LeBel says. “Unfortunately, fresh fruit and vegetable margins are not all that high. There’s a lot of waste. So maybe 12, 15 years ago, Loblaws and [other supermarket chains] started changing the planogram. Now they might start with the ‘Grab and Go’ buffet, because they’re competing with restaurants. A lot of people, instead of going to a Burger King or McDonald’s, might swing by the supermarket, grab a wrap, a salad or whatever. So they’ll put that section first, followed typically by baked goods.”

Planograms are likely to keep changing. Research firm Grocery Doppio recently found consumer habits have been shifting, possibly as a result of widespread use of weight-loss drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro. In the first half of 2024, U.S. sales of whole fruits and vegetables were up 13 per cent, while sales of snacks and confectionary purchases like chocolate, candy and sugar-coated treats were down 52 per cent. Sales of prepared baked goods were down 47 per cent.

There are two phrases beloved by grocery retailers, LeBel says: “Grow the basket” and “Win the trip.”

“So, ‘Win the trip’ — every supermarket trip has a mission, a purpose,” he says. “It might just be to pick up milk, or I’m missing some vegetables for tonight’s dinner, I need to find a side, or bread, or whatever. But the trip may be a bit more complex — I’m hosting friends on Saturday, and I want to impress. You as the retailer, if you understand what that mission or that purpose is, you arrange things so that it’s easier for the customer to find. You get to the fish counter, you’ve got your salmon, your lemon, your dill, all put together for you. It’s about arranging items that go together to meet the purpose of the trip. So the croutons and the vinaigrette go with the salad, not in separate aisles. You fulfil the mission efficiently at a decent price, finding everything that you need in the 15 minutes that you have. It works great in theory, although it’s not always well executed in practice.

“The other expression in the industry is ‘Grow the basket.’ Say you ordered a cake for your kid’s birthday. Well, you have fancy candles at $3.99 a candle. And if your kid is older than 10, then you will need two candles. That’s an insane profit margin, and it grows the basket. That’s why, over time, we’ve seen supermarkets have more and more products that are complementary. They’re not necessarily food related — kitchen gadgets, storage containers, things like that — because it grows the basket. Then you walk out and say, ‘Damn, I expected to spend $100 and I’m up to $120,’ because this market arranged things in a way that suspended your rationality and managed to grow the basket.”

To some extent, we consumers are all like Wile E. Coyote wandering through Acme Mart. Do you really need that box of gunpowder? Is it wise to buy another anvil? You have so many. But Acme knows its customers. That’s why they always put the rocket sleds near the cash register.

“When people are in a rush, they’re going to make decisions not so much based on logic, but based on emotional states,” says Dr. Steven Taylor, professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia.

“I’ve become very interested in nudges. Nudges are kind of low-effort, low-impact attempts to steer people in particular directions. Probably the most prominent sort of nudges are candy bars in checkout aisles. If they put fresh fruit and veggies there, you will be nudged to buy fresh fruit and veggies. Those sorts of things, they’re not subliminal, but they exert their impact without people thinking about them a lot. They’re setting things up for impulse buying. And people tend to buy things that bring them comfort.”

The costs of ‘shrinkflation’

A canny shopper learns to recognize certain subterfuges practised by big retailers. The one that has received the most attention lately is “shrinkflation.” Instead of raising the price of an item, manufacturers put less product into the same size of package. It’s sneaky, but it also highlights a common consumer failing: a lack of attention.

Any good shopper ought to check price against volume, judging a deal not simply by the dollar amount but by calculating the price per gram, ounce or millilitre. But stores and manufacturers are betting you won’t. They’re betting you will just grab the box and go. (A long-standing variation of this tactic is the individual-serving package — eight little yogurt containers, perfect for the kiddies. Look, there’s eight of them! Just don’t add up the volume and compare it to the price of a 750‑gram container of the same yogurt, which not only is likely to be cheaper per gram, but also produces less packaging waste.)

What can you do about shrinkflation? The only effective response is to say no. Don’t buy it. You’ll save money, and if enough people do the same, the message will arrive on the corporate bottom line.

Meanwhile, a 2024 CBC News investigation discovered that meat products in Canadian supermarkets are often underweight — stores are charging not just for the weight of the meat but also for the weight of the plastic packaging, a practice that is illegal.

It’s not just meat products, either. In May 2024, a TikTok video by Vancouver shopper Jacob MacLellan showed that a bag of frozen vegetables purchased at Loblaws, labelled as 750 grams, was actually a measly 434 grams. Most stores still have scales in the produce section — it’s a good idea to weigh the packages you select.

As I swing my basket up and down the aisles in search of bargains, I often wonder how sale prices are determined. If a product is offered as a weekly special, was it the store that made the decision to offer a discount, or the manufacturer?

It’s not straightforward, according to Dr. Sylvain Charlebois. The Halifax-based grocery retail analyst who calls himself the Food Professor says discounts usually originate with the vendor (i.e., the product manufacturer), but can also be initiated by the supermarket.

“Pepsi may have a new product and will negotiate with Loblaws and Sobeys, a promotion around the Super Bowl, for example,” Charlebois says. “So that would be initiated by the vendor. But if Loblaws wants more traffic in the bakery department they might go to [Mexican baked-goods conglomerate] Grupo Bimbo and basically say to them, ‘OK, we can promote some of your products to give our customers an excuse to go and visit that area, because margins are higher.’ It’s all about volume.”

Charlebois also explains a particular annoyance of mine: Why is it that whenever I see a store flyer from Ontario, there are bargains on offer that we on the West Coast would kill for?

“Competition and transportation,” he says. “Ontario benefits from the St. Lawrence Seaway, it benefits from the Montreal port. Then there’s population density. Sixteen million people in a province, and right next door you’ve got Quebec as well. So it’s easier to develop economies of scale. The middle mile is more efficient — that’s the warehouse-to-store mile, and that is way more efficient in Quebec and Ontario. Whereas in B.C. you have to truck in a lot of the stuff. If it doesn’t come through the Port of Vancouver, or through the United States, it comes through the mountains, and that tends to cost a little bit more. Our food in Atlantic Canada is just as expensive as in Vancouver.”

None of that explains why corporations sell the same products for different prices at different stores. “It really irks me when you see a product in one place for $6.99 and at another place, which is owned by the same mother corporation, for $1.50 less,” LeBel says.

“Wait a sec, it’s not like you’re providing me with atmosphere. There’s no musician playing jazz when I come in. There’s no difference, no additional fluff. I think consumers are growing aware of this, because with the pandemic and inflation, people got back into that mode of shopping around.”

What do loyalty programs really yield?

Every store has its loyalty points program. I belong to at least three. Apparently that places me far below the average. A market analysis website called Exploding Topics reports that as of 2022, the average American consumer belonged to 16 different loyalty points programs.

I have long been skeptical of such programs. My skepticism remains, but it has been tempered a little. You can indeed save some money with loyalty cards, but there are traps to avoid.

It has become standard practice now for grocery retailers to offer “sales” that involve not price discounts but extra loyalty points. I avoid those pitches entirely. A discount should involve price, and anything else seems to me — more or less — a ruse. If you are getting extra points for buying a particular product, you are probably paying too much. Points are almost never offered for discounted items. If you shop strictly for the best prices and the best deals, you will rarely acquire loyalty points.

As an example, I have been a member of PC Optimum, the loyalty program for stores including No Frills, Loblaws and Shoppers Drug Mart, for several years now. I scan the card at the checkout with every purchase. Over that time, shopping at No Frills month after month, year after year, I have accumulated a little over 2,000 points. I would need 10,000 to qualify for a $10 discount.

In spite of years of loyal patronage, my meagre points total is useless. On occasion, though, I have qualified for a specific Loblaws discount offered to PC Optimum card holders. That kind of direct discount is the best reason to have a loyalty card.

On the other hand, the Scene+ card used by Safeway, Sobeys, FreshCo, the Cineplex theatre chain and others has sometimes paid off for me. Again, I never buy a product specifically to get points, but with the Scene+ card I have accumulated sufficient points to earn a few $10 discounts. The difference appears to be that the points are more valuable. Earning just 1,000 of them was enough for a $10 discount.

Go ahead and sign up for a loyalty card — no harm in that. With any program, though, I feel shoppers are better off ignoring points-based pitches completely. If you acquire points anyway, great. But if you chase them, you’re likely to end up spending more than you save.

‘It’s true that some discrimination is required when bargain shopping — but for the most part the fears are unwarranted.’ Photo via Shutterstock.

‘It’s true that some discrimination is required when bargain shopping — but for the most part the fears are unwarranted.’ Photo via Shutterstock.

Behind the red stickers

Supermarkets have other little tricks. “Buy three for five dollars,” for example. Is it necessary to buy three to get the discount? Sometimes it is — you must look to see if the price for a smaller quantity is listed in smaller print. Most of the time, though, three for five dollars or two for three dollars simply means one for $1.66, or one for $1.50. No need to get the complete set. Plus, when you do the math, you may find the three-for-five-bucks price is not that great. They are banking on our reliably poor math skills.

Another little ruse is the bogus shelf tag — some stores will put up a tag that resembles those identifying weekly discounts. But look closer and the tag simply says “Great price!” It may well be a great price, but the product ain’t on sale.

Later, full-price Oreos. A variation: a bright-yellow sales tag beguiles you to scoop this deal, and you do, but without noticing that the item has been discounted by a whopping three cents. “Our brains are like, ‘Oh, a deal,’ right?” LeBel says. “It’s like a serotonin or dopamine hit — oh wow, I just scored a deal. And you don’t think, you just add to cart.”

This reaction is so common that bogus discounts have become a full-time strategy for some retailers. In the spring of 2025, Vancouver law firm Slater Vecchio LLP launched a class-action lawsuit against the Gap and Old Navy clothing stores, claiming that “sale prices” advertised online were more or less permanent. “It is alleged that Gap and Old Navy rarely, if ever, offer to sell their products at the represented regular price and instead always, or almost always, offer these products at the so-called discount price,” the suit alleges. Among the findings of a CBC Marketplace investigation was a particular Old Navy item that was on sale 98 per cent of the time.

Each grocery chain has its discount method. The approach of Loblaws — which owns No Frills and Superstore, among many others — is to attach red stickers on products approaching their expiry dates: 30 per cent off meat products, 50 per cent off produce, bakery and other items. Safeway, FreshCo and Thrifty’s, among others, opt for specific dollar discounts, applying stickers for one, two, even up to 10 dollars off an item.

These stores also put 50 per cent clearance stickers on certain items, usually located on a clearance shelf or in a shopping cart. Clearance baskets occasionally offer up a winner — I recently bought a half-price container of salt at Safeway and I’m pretty sure it is not going to go bad next month.

More often the clearance cart contains a jumble of retail also-rans, losers in the consumer product wars. Personally I don’t need mango-scented dryer sheets, but you may feel differently. However, there are no good prices on useless items. If you buy a half-off box of gluten-free budgie food on the off chance you might someday acquire a bird with finicky digestion, shame. You wear the checkered costume of a fool.

Navigating these discounts is a learned skill. The Safeway dollar-based discount, for instance, requires a different approach than the Loblaws percentage discount. If a selection of Safeway hamburger packages all carry “Two dollars off” stickers, the trick is to find the smallest package. Two dollars off a 500‑gram package is a better deal than two dollars off a 600‑gram package — the price per gram will be lower. Whereas if the discount on all packages is 30 per cent, size is not an issue.

As important as it is to find those red stickers, it is just as important not to vacuum them all up like some filter-feeding whale. An expensive item that’s 30 per cent off can still be expensive. I often see discounted packages of steak or beef roasts. But aside from being, to me, less versatile than pork or chicken, I usually find good cuts of beef too expensive, even at a discount.

The stickers are popular. The uproar across Canada in 2024 when Loblaws announced plans to phase out “50 per cent off” stickers (they quickly reversed the decision) suggests that such discounts are highly sought after. Yet many shoppers are wary of discounted items, especially meat and dairy products, for which freshness and shelf life are factors to consider.

What best-before dates really mean

It’s true that some discrimination is required when bargain shopping — but for the most part the fears are unwarranted.

An employee in a Safeway meat department once told me that when Canada Safeway stores were purchased in 2013 by Empire Company, owners of the Sobeys grocery chain, the policy on stickering meat packages was changed. Sobeys guidelines called for discount stickers to be attached a day earlier. So when you buy a newly discounted package of hamburger at a Canada Safeway, you are buying something that a dozen years ago would have carried a full price.

Expiration dates are often viewed by shoppers as the day a product will go bad. On that date, weeping family and friends of the expired spinach will gather round as it is committed to the soil from whence it came. But this is rarely the case. Expiration and use-by dates are also frequently confused with less strict best-before dates, sell-by dates or the somewhat hectoring “Enjoy tonight!” sticker. Even Twinkies have best-before dates. And they are actual calendar dates, as opposed to “∞.”

But it’s a question of quality, not of food safety. Even expiration dates, the sternest of the warnings, are not predicated on the idea that delayed consumption might lead to slow, agonizing death.

“What is the safety issue?” asks Lori Nikkel of the organization Second Harvest. “There’s no safety issue. It’s bullshit. There is a nutrient issue, but it’s not about safety.”

Second Harvest is dedicated to preventing waste and rescuing food that would otherwise be disposed of. Nikkel supports the display of manufacturing dates, so consumers can see when the product was made, but believes that otherwise, consumers are perfectly capable of using their own judgment.

“We don’t need these best-before dates. We’re smart enough. We know when our food’s bad, and we won’t eat it. And we know that when it’s bad, it’s not poisonous. It won’t kill us.”

There are only a few products that carry actual expiration dates. It’s not because they become deadly, but because their crucial nutritional value declines. According to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, an expiration date on a package indicates a product that has “strict compositional and nutritional specifications which might not be met after the expiration date.” Meal supplements, protein bars and infant formula are the only Canadian products that carry expiration dates. Infant formula is the only product for which an expiration date is mandated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. I have strategically arranged my personal circumstances so as to avoid the stuff altogether.

Perhaps the public’s strict interpretation of safety labelling took hold because expiration dates were first applied to milk products, something that, as one might learn by experience, truly does have a limited shelf life. Legend has it we owe this innovation to gangster Al Capone, who supposedly fought for expiration dates on milk bottles after a family member became ill from drinking bad milk.

The practice of dating products gained wider use in the 1950s thanks to Marks & Spencer. The British retail chain first introduced best-before dates in the stockroom as a guide for employees. In the early 1970s, an ad campaign starring supermodel Twiggy introduced best-before dates to the public, as the chain moved to convince customers that its food products were fresh. The practice quickly spread to other retailers.

Interestingly, Marks & Spencer has since gone in the opposite direction. In 2022, as concerns about freshness gave way to concerns about massive food waste, Marks & Spencer began removing use-by dates on over 300 produce products.

Dairy remains the category in which expiration dates probably carry the most weight. The date stamped atop that carton of milk is indeed an approximation of the product’s usable lifespan. “But here’s the thing,” Nikkel says. “Your milk goes bad, it smells bad, you’re not going to drink it. So there is this kind of mental disconnect in terms of, ‘If it’s bad I wouldn’t use it anyway.’ You’re not actually relying on that date.”

Yogurt has a much longer viability than milk, and cheese is almost never a problem. (John Updike described cheese as “milk’s leap toward immortality.”) With age, soft cheeses will develop a stronger flavour that some may not enjoy; hard cheeses may develop mould on the surface.

It is difficult to convince many consumers of this, but once you scrape off that mould the cheese is still perfectly good. Surface mould is not indicative of spoilage. (Once upon a time, Safeway would give you a solid discount on a mouldy block of cheese — I used to scour the dairy case looking for compromised packages — but unfortunately they discontinued that policy in favour of simply removing such items and disposing of them. Phoo.)

Meat products in particular give some shoppers the willies. It is interesting though that the serious food scares in recent years have had nothing to do with best-before dates, and often nothing to do with meat products. It’s usually E. coli, listeria and salmonella contamination in everything from walnuts to basil to bean sprouts. A 2011 listeriosis outbreak caused by contaminated cantaloupes killed 33 people in the U.S. Expiration dates had nothing to do with it.

The thrill of the hunt

I have had food poisoning all over the world. You could make a dazzling travel itinerary strictly out of places where I have suffered food-borne illness. Yet every wretched episode was the result of a restaurant meal or, in a couple of cases, a street food item. I have never poisoned myself at home by buying discounted groceries.

For cheap produce I usually shop at local markets. Trial and error will give you a sense of which discounted products ought to be avoided. If you enjoy arugula in your salad, alas, you will probably have to pay the going price. Discounted arugula is a bad bet. Its precious prime is a brief candle, soon extinguished. Once it starts yellowing, forget it.

A discounted avocado is a desperate gamble. I have boldly rolled the dice many a time, because I love avocados and those things are like green gold. (Not to mention the meal-planning aspect — buying a fresh, unripe avocado means you have to start thinking about your dinner plans for next Monday.) They’re not a necessity — you can make a decent taco without them — but still, a nice ripe avocado is a joy, and if you score a good one it’s available immediately.

How, then, can you tell when an avocado is fatally compromised? Any major denting in the skin is trouble, and too much give is probably a sign that you will peel it to find the grey-brown ruins of a failed bet. Unlike a banana, there’s no use for a late-stage avocado. Your discoloured guacamole will cost you friends.

It’s fun, anyway — browsing for vintage vegetables, slightly worn and frayed, like blue jeans from a thrift shop.

For those whose financial circumstances hamper other types of shopping, a grocery run can take the place of buying shoes or electronics. It offers the thrill of consumer activity and, done right, leads to actual consumption.

It’s true that not every peach is an inner, but the buyer’s remorse, if there is any, is minor.

Still, it takes a certain type of person to engage in this sort of bargain hunting. Such people have been depicted in story and song over the years. The depictions are rarely flattering.

‘Chapter Two: Eye of the Owl’ from ‘Cheapskate in Lotusland: The Philosophy and Practice of Living Well on a Small Budget,’ Steve Burgess, 2026, Douglas & McIntyre. Reprinted with permission from the publisher. ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/design-article.thetyee.ca/ui/img/yellowblob.png)