This time, at least, government officials and Abbotsford residents have heard of the river barrelling down on the Canadian border.

Just four years after Sumas Prairie flooded in 2021, floodwaters from the Nooksack have again begun to cross over the border.

Images from Sumas, Wash., show heavy flooding in that low-lying border community.

In the span of an hour this morning, the border community of Sumas, Wash., was inundated by floodwaters from the Nooksack River, 10 kilometres to the north. Camera stills via the Washington State Department of Tr…

In the span of an hour this morning, the border community of Sumas, Wash., was inundated by floodwaters from the Nooksack River, 10 kilometres to the north. Camera stills via the Washington State Department of Tr…

This time, at least, government officials and Abbotsford residents have heard of the river barrelling down on the Canadian border.

Just four years after Sumas Prairie flooded in 2021, floodwaters from the Nooksack have again begun to cross over the border.

Images from Sumas, Wash., show heavy flooding in that low-lying border community.

In the span of an hour this morning, the border community of Sumas, Wash., was inundated by floodwaters from the Nooksack River, 10 kilometres to the north. Camera stills via the Washington State Department of Transportation.

In the span of an hour this morning, the border community of Sumas, Wash., was inundated by floodwaters from the Nooksack River, 10 kilometres to the north. Camera stills via the Washington State Department of Transportation.

The City of Abbotsford is posting regular updates online.

Evacuation orders have been expanded, and farmers have been working to remove livestock from properties at risk.

The Nooksack river peaked at 3 a.m. According to Abbotsford officials, data suggests a flood similar to that seen in 1990, but smaller than the 2021 event. The 1990 flood inundated properties on the western side of Sumas Prairie and closed Highway 1, but did not breach the dikes that protect the Sumas lakebed.

Provincial officials have warned that Highway 1 between Chilliwack and Abbotsford may close with short notice as floodwaters rise. DriveBC is the best source for updates on road closures.

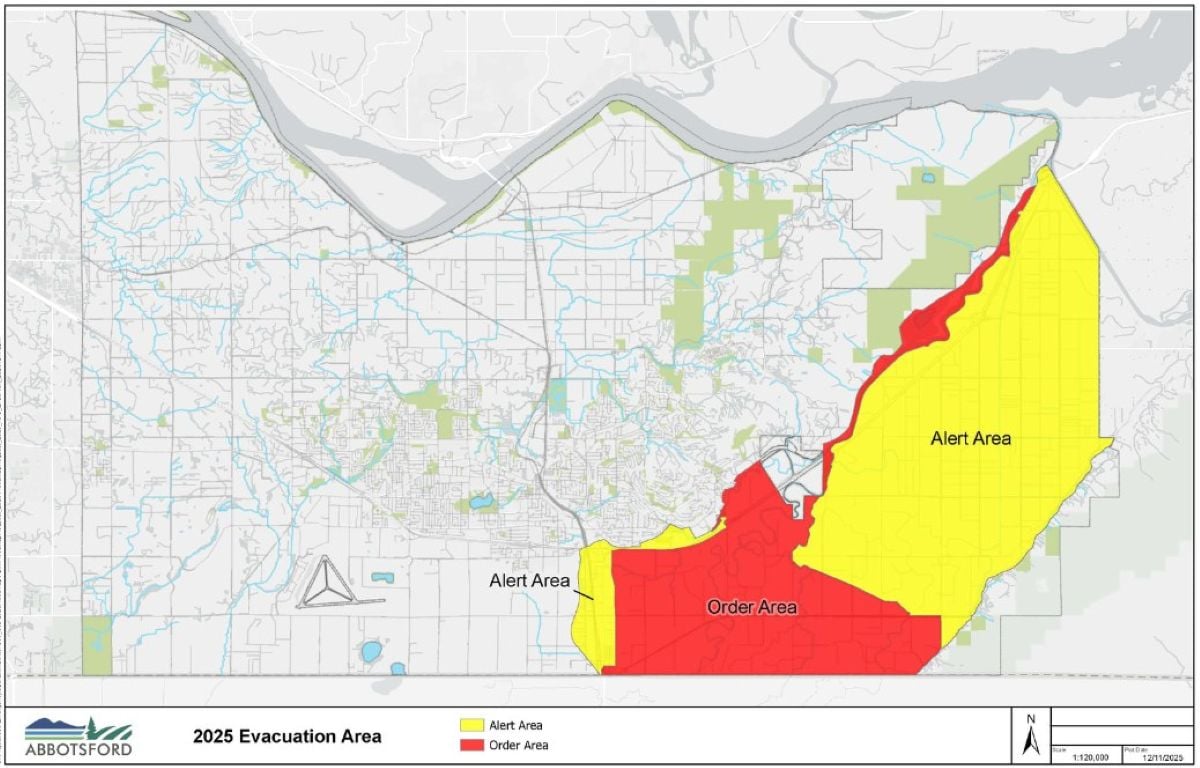

Evacuation orders have been issued for the western part of Sumas Prairie. An alert is in place for the eastern part of the prairie, which is protected by a dike. Map via City of Abbotsford.

Evacuation orders have been issued for the western part of Sumas Prairie. An alert is in place for the eastern part of the prairie, which is protected by a dike. Map via City of Abbotsford.

What’s been done to prepare for this flood?

Any analysis of flood prep work inevitably ends up as complex as the Nooksack River itself. For a relatively short river, there may be no other watercourse with so many factors complicating efforts to reduce its flooding risks. The challenges range from the very local, including the impact of a key bridge crossing, to the international — like the relationship between Donald Trump and Canada.

But the complexity of the river and its flooding challenges do not mean that nothing can be done to mitigate its risk and penchant to flood.

As The Tyee reported last month, Canadian and U.S. politicians at various levels of government pledged to co-operate to find ways to reduce the Nooksack’s threat immediately following the 2021 flood. In the years since, work has proceeded, albeit slowly, on some key efforts. At the same time, momentum has lagged and the federal government has seemingly walked away from verbal commitments made by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in the wake of 2021’s flooding.

On Wednesday night, Emergency Manager Minister Kelly Greene said the federal government has been absent from flood mitigation conversations. And Abbotsford officials remain deeply aggrieved that the federal government has rejected funding applications despite promises made by Trudeau and his ministers immediately after 2021.

With water rising in Sumas Prairie, the region is better prepared in some ways. There have been improvements to flood warning systems, alignment in U.S. and Canadian hydraulic modelling, and some infrastructure improvements. Other fixes remain elusive for a range of reasons ranging from concerns about fish impacts to a lack of government funding.

On Thursday, water from the Nooksack River continued to pour into the watershed of the Fraser and Sumas rivers. Camera still via the US Geological Survey.

On Thursday, water from the Nooksack River continued to pour into the watershed of the Fraser and Sumas rivers. Camera still via the US Geological Survey.

What is better

The single largest improvement from 2021 is the fact that officials across B.C. were very aware Wednesday of the potential for flooding from the Nooksack and its impact on Sumas Prairie.

Officials were caught flat-footed in 2021, when there were few public warnings to residents and drivers about the threat it posed. Evacuation orders and alerts were slow to be issued, and Highway 1 was closed abruptly with no notice to people who might be stranded. The fact that a U.S. river could flood north of the border seemed to have caught Canadians totally off guard.

This time, the City of Abbotsford and the province have been issuing regular proactive announcements about the potential for flooding from the Nooksack, starting more than 18 hours before floodwaters arrived.

That gave travellers time to prepare for highway closures, farmers time to figure out contingency plans for their animals, and residents time to prepare children and other vulnerable populations.

Messaging by local officials was augmented and informed by better communication with officials south of the border. The awareness will also give transportation crews the ability to proactively create a “tiger dam” on Highway 1 that could help better funnel floodwaters toward the Fraser and away from the Sumas lake bed.

In terms of tangible improvements to redirect water, there have been a few advances — albeit relatively small compared to the scale of the challenge.

The City of Abbotsford has spent the last few years trying to address the most immediate, small-scale issues created and exposed by 2021’s floods and landslides. The city’s 300-item long list of projects included dredging ditches, removing debris from waterways, and stabilizing the bank of the Sumas River.

One key improvement was the building of a new flood wall to protect the Barrowtown Pump Station — the massive facility that nearly flooded in 2021. If Barrowtown were to have flooded, Sumas Prairie could have remained under water for months. Only the dramatic efforts of local volunteers let the facility remain in operation and allowed the draining of the prairie over the course of a couple weeks, instead of months.

South of the border, at the spot where the Nooksack flooded, there has also been some work, though results have varied.

Whatcom County officials boosted river capacity near a key choke point in the small town of Everson. Officials have also worked to improve “water storage” — essentially finding places where floodwaters can be accommodated in non-harmful ways.

There have also been major efforts to install more gauges, and study the river itself to better understand what happens when water rises.

The Nooksack’s uniquely complex geography makes everything more difficult. The river origins on the slopes of Mount Baker can leave it full of woody debris and sediment when it spills onto the vast floodplain south of Abbotsford.

As the river slows and drops its sediment load, that sediment changes the flow of water. In a natural environment, the river would shift dramatically over the course of years. Humans, though, pen in waters, reducing their ability to move around sediment.

Paula Harris, Whatcom County’s flood manager, told The Tyee in November that they are still calibrating models to better understand how debris, sediment and high flows impact the water flow.

“We’re learning a lot, where we’re starting to try and figure out what the implications of if we do something, how will that affect things?” Harris said.

What hasn’t been done

There are three major potential projects with potential to significantly impact the Nooksack’s threat to Canadians. None of them have seen much headway over the last three years.

First: south of the border, locals along the river have been agitating for years for officials to dredge the river and remove large quantities of sediment. As the Nooksack enters its broad, flat floodplain at the base of Mount Baker, it deposits large amounts of sediment both along its banks and on the river bottom. With the river unable to chart a new course, locals say the sediment raises the level of the river, increasing the Nooksack’s flood threat.

There is some debate about just how much of an impact the sediment has on flooding when it reaches the scale seen in 2021. The sediment’s impact on water heights decreases as the volume of water increases. Understanding the benefits — or lack thereof — of dredging is key because sediment removal can have significant impacts on the salmon that spawn in the Nooksack.

Second: Canadians and officials in Abbotsford want the Americans build a dike along the Nooksack at the spot where floodwaters spill out of that river’s drainage basin and into the Sumas/Fraser River’s basin. That spill point, called the overflow, is relatively narrow, and a dike could be built.

But American officials have been hesitant to do so because retaining more water within the United States would increase flood damage in communities downstream. While Whatcom County officials have discussed the potential of altering the “flow split” — the amount of floodwaters heading either north or west during a major flood, those talks have not yet turned to action.

Whatcom County has made some gentle effort to reducing water heading north. This year, a row of very large sandbags was placed along the road where the water often crosses from the Nooksack drainage to the Sumas drainage. Those sacks, however, proved to be insufficient and were overwhelmed by the arrival of floodwaters. Images from the site show one sack, then several, then the whole line disappearing as floodwaters breached the makeshift dike.

Third: a final set of remedies has been proposed in Abbotsford itself, where the city has sketched out a $1.6 billion plan to reconfigure dikes and build a new pump station that could convey more floodwaters to the Fraser River.

Any such project would also require raising Highway 1 through Sumas Prairie. The project is so expensive that Abbotsford cannot pay for it on its own. While Siemens and Fraser Valley officials have stressed the importance of Sumas Prairie both as a transportation corridor and a source of local food, the federal government has yet to provide any indication that it would help fund for the project. Last year, it rejected applications from Abbotsford, Merritt and Princeton for funding for major flood prevention works. Abbotsford’s dike-and-pump-station project was among those rejected.

Sumas Lake

Much of Sumas Prairie was once a lake, before it was drained a century ago, with major consequences for local Sto:lo communities. The lakebed now sits near sea level, and can fill up if the dikes that protect it fail, as they did in 2021.

Some have advocated for policies that would allow the lake to return. The city, the province, and Abbotsford officials have all pushed back against the suggestion, highlighting the importance of the prairie as a food source and the critical infrastructure crossing the prairie. Sema:th First Nation’s chief has declined to push for the lake’s return, saying it shouldn’t return if local residents object. He has instead suggested work be done to increase natural wetland areas in the prairie area.

The lake issue is only tangentially related to the Nooksack itself. The lakebed does not normally form part of the Nooksack’s drainage basin, although it and surrounding land would accommodate floodwaters without the existence of dikes. Whether or not the lake itself exists or not, the occasional redirection of the Nooksack north of the border would still dramatically reshape the landscape and require humans to adapt to a unique river that flows two ways.

Climate change

The Nooksack has always posed a flood threat to Abbotsford, but that risk appears to be significantly increasing. Climate change is a major factor.

The river drains the slopes of Mount Baker, one of the world’s snowiest places. But the scale of the mountain and its foothills, and its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, means it can also be one of the rainiest places. The relationship between those precipitation types can be highly influenced by even slight shifts in climactic patterns.

Every degree of temperature increase causes snow levels on Mount Baker to rise by about 150 metres, on average. An atmospheric river that hits in 10 C weather will deposit vastly more water on the slopes of Mount Baker than a similar event in slightly cooler weather. Those warmer temperatures are predicted to “drastically” increase the Nooksack’s flood risk over the next 50 years, according to a recent study.

“In the future, we’re expecting to see a smaller snowpack and therefore a larger area that is exposed to runoff, and therefore, that water is getting to the river quicker and therefore we see higher peak flows,” the study’s author, Evan Paul, told me last year.

The future may already be here. ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/design-article.thetyee.ca/ui/img/yellowblob.png)

- Share:

- **