A disheveled panhandler, clutching a Santa hat and sporting a terrible fake beard, sits on a curbside, flanked by minimalist holiday decorations out of place with the glaring summer sunlight. A smartly dressed man, surrounded by bodyguards, strides up and lays the following introduction on the audience: “Boss, you’ve been working undercover as a homeless man for six months now to investigate your uncle’s crimes. Now that your uncle’s in prison, it’s time for you to return to the Jones Group.” You see, the bearded man isn’t actually homeless. He’s the title character of Found A Homeless Billionaire Husband For Christmas, an ideal example of a vertical drama—a type of shortform,…

A disheveled panhandler, clutching a Santa hat and sporting a terrible fake beard, sits on a curbside, flanked by minimalist holiday decorations out of place with the glaring summer sunlight. A smartly dressed man, surrounded by bodyguards, strides up and lays the following introduction on the audience: “Boss, you’ve been working undercover as a homeless man for six months now to investigate your uncle’s crimes. Now that your uncle’s in prison, it’s time for you to return to the Jones Group.” You see, the bearded man isn’t actually homeless. He’s the title character of Found A Homeless Billionaire Husband For Christmas, an ideal example of a vertical drama—a type of shortform, phone-native, movie-like content produced by companies claiming millions upon millions of American users, all while being deeply exploitative trash.

The world of vertical dramas is an addictive, algorithm-powered economy with unbelievable dollar totals and salacious, absurd films with titles like In Love With A Single Farmer-Daddy or Help! My Hot Boss Has My Nudes! This all-too-real niche has been popularized over the last few years by a handful of Chinese-backed American corporations, producing content that is utterly alien in composition and laughably amateurish in execution, in pursuit of maximum profit. It might be the most purely cynical form of entertainment currently in production; concepts formulated and pitched by robots to other robots, to separate humans from dollars.

The typical vertical drama is a three-act feature between 90 and 100 minutes, chopped up into 60 to 80 chunks, which are referred to as “episodes,” as if you’re watching the fastest, bluntest TV series ever made. In the U.S., a few dozen competing companies produce indistinguishable vertical dramas this way, but the two biggest are ReelShort and DramaBox, each of which claims more than 50 million unique monthly users. If they’re to be believed, vertical dramas are the most popular films being made today.

The defining feature of each vertical drama mini-chunk is the rise and fall of tension over the 90- to 120-second cycle: Characters appear with subtitled descriptions of who they are, as voiceovers announce “I’m ____, and I feel ____ about ____.” These characters converse, argue or flirt, a threat arises (such as the reveal of a secret identity or a potential humiliation), and then it cuts to a brief black-screen cliffhanger. The next “episode” begins, the hurdle is instantly overcome, and the process starts again. The entire thing is predicated upon the viewer not remembering the previous rug-pull that happened two minutes earlier, and two minutes before that. It’s the apex of goldfish-brain entertainment, taking the ethos of an old Flash Gordon serial and distilling it into content consumed in marathon sessions.

ReelShort’s slogan boasts that “every second is drama,” and that the company’s mission is to create “fast-paced drama for busy women,” among other things. Indeed, it quickly becomes obvious that women are overwhelmingly the target demographic, although nailing down a generational window is more tricky. The gamified, “coin”-based economy involved in purchasing these vertical dramas smacks of the mobile game addiction common to Gen X and Boomers, but the style of content reaches far past your aunt who has sunk $20,000 into Candy Crush Saga, displaying more prominent Gen Z hallmarks, like universally hardcoded subtitles. Perhaps the most important descriptor is “busy,” which could just as easily be “attention deficient.” Ads depict scenarios like a woman getting into an elevator and having just enough time to watch the next 90-second episode before continuing on with her day. If that sounds suspiciously similar to the pitch for Quibi, it’s not far off—but replacing the A-list stars, ambition, and big budgets with non-actors, laughable production standards, and salacious premises.

Vertical dramas were born in China (where they’re referred to as duanju) during the 2010s, before exploding into widespread popularity there during the quarantine era of the COVID-19 pandemic. The leading production/exhibition companies in the U.S., like ReelShort and DramaBox, trace their ownershipback to Chinese conglomerates, and much of the content has itself been transliterated from film scripts originally written in Chinese or Korean, with American production teams employed to hastily localize the stories. The almighty algorithm rules everything: If any given vertical drama proves popular, the companies immediately greenlight several more that repeat it almost verbatim, right down to confusingly similar titles. And this doesn’t just apply to broad themes—vertical drama producers also identify small, individual elements or story beats (such as a woman being bullied and slapped) and then repeat that element in every production until it stops driving engagement. This gives your average vertical drama an intense feeling of uncanny familiarity once you’ve watched a few. Repetition is a feature; the core consumer apparently just wants more of the same.

To feed that addiction, they’re going to pay through the nose. Vertical drama apps are built to obfuscate the sense of how much you’re paying, with “coins” purchased in bulk, in amounts from hundreds to thousands. Individual episodes might cost upward of 60 coins per two-minute piece of footage—and given that each drama has 70 or more episodes, this means the viewer can easily spend $20 or $30 to watch 90 minutes of some of the cheapest slop imaginable. People are paying much more to watch Tricked Into Having My Ex-Husband’s Baby on their phones than it would cost to see *Sinners *in IMAX.

It’s difficult to trust the markers of popularity vertical drama producers boast about. Viewership metrics often seem absurd or impossible—already a common experience with streamers, which tend to withhold view numbers, or speak in vague and misleading terms about how many people are watching. Vertical dramas, on the other hand, tend to directly provide extremely gaudy viewership numbers: *The Washington Post *wrote that ReelShort’s How To Tame A Silver Fox had been “watched 356 million times,” which would work out to more than one view for every member of the U.S. population. ReelShort now claims “393.5 million” views for that film. Is it more likely that How To Tame A Silver Fox is one of the most beloved and widely viewed films in human history, or that ReelShort has added together the views of the 70+ “episodes” to reach that final number? This number-fudging isn’t even necessary: If you divided by 70, it would still imply more than 5.6 million views for this single vertical drama, which is a shocking enough figure. But the companies can’t help themselves from aggrandizing these accomplishments.

Vertical dramas are also dirt cheap and lightning fast to make—we’re talking budgets of $100,000, and filming schedules of a week or less, allowing a project to progress from pitch to release in the space of a few months. Pay for most of the performers is necessarily low, but it’s still enticing to those looking to break into the industry, and there’s no shortage of obvious non-actors supplementing their ranks in every production. The monolithic players of the entertainment industry, meanwhile, are clearly paying attention to the lucrative nature of vertical dramas, which would seemingly disprove the need for massive budgets, CGI, or star power. Disney made DramaBox one of the participants inits 2025 Accelerator Program, “to help Disney innovate in short-form content, with plans to adapt Disney’s book properties into these bite-sized series for new audiences, focusing on emotional hooks and rapid production for platforms like TikTok and Reels.” Netflix has likewise already stated its intention toproduce more vertical video content, which has thus far been interpreted as some kind of plan to ape TikTok. Consider instead, the possibility of an entire wing of Netflix’s mobile app dedicated to vertical dramas.

If millions of Americans are consuming vertical dramas on a daily basis, what exactly are they watching? The answer is a hodgepodge of genres, primarily fitting into romance, fantasy, and thriller buckets. Subcategories include everything from “wallflower” to “janitor,” “protective husband,” “twisted lover,” “chef,” “super warrior,” “CEO,” and“rugged CEO,” which ReelShort separates into an entirely distinct category. Some titles reek of crude translations (Marry To Top Star At 40s) or keyword-cramming (Forced Into An Arranged Marriage, Only To Find Her Fiancé’s Uncle Is Her Now-Successful Ex).

These stories ape the zeitgeist, whether that means Hallmark-style holiday features, costume-driven royal intrigue stories, kink-centric workplace dramas, or timeless fantasies of being whisked away from mundanity by a fabulously wealthy man who can solve all of life’s problems. Most any sports niche is also well covered—especially hockey, even in advance ofthe viral success of Heated Rivalry. The most common approach appeals to women with fetishes for being controlled by dangerous, violent men with the most slight of redeeming qualities. This dynamic is especially present in the “mafia” and “mob” genres, in which mousy heroines find themselves abducted or indentured into the service of chiseled male mafiosos who occasionally threaten them with death or torture, but also possess secret hearts of gold. He may be a prolific murderer, but he also tells the female lead that “you make me want to be a better man.” A number of these stories involve women being forced to abandon their lives, only to be transformed into contented tradwives for powerful men. Titles in this niche include Bound By Honor: Kidnapped By The Mafia King, My Sugar-Coated Mafia Boss, andFalling For My Ex’s Mafia Dad, the latter of which doubles as an example of the prolific subgenre in which young women are enchanted by older men connected to their families or former lovers. These are countered by the “reverse harem” films, in which a woman is courted by a squad of hot, single-trait guys.

Romantasy is also a major player, but it goes beyond simple mimicry ofA Court Of Thorns And Roses—the very style of romantasy prose influences how almost all vertical dramas handle the protagonist’s perspective. Universal, audible inner monologues coax the viewer to insert themselves into the fantasy. The ReelShort category “Magic & Mates” spins more variations on women indentured to werewolf “alphas” than you could possibly imagine.

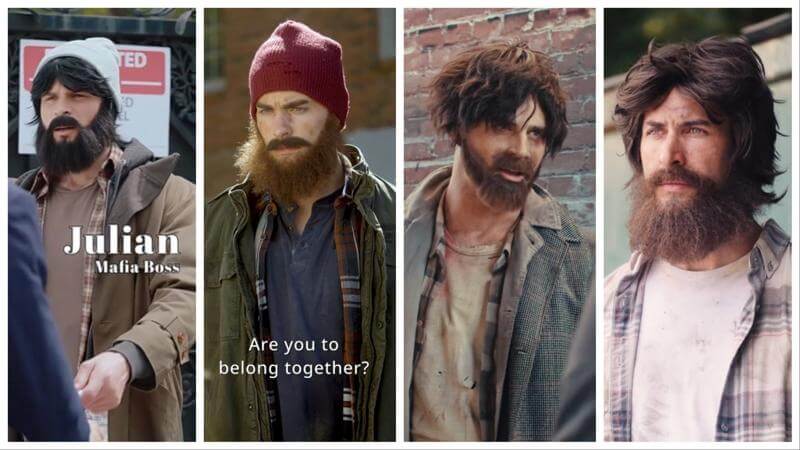

Then there are the aforementioned “billionaire” stories, which involve 27-year-old captains of industry masquerading as janitors or vagrants, only to fall in love with gig economy workers unaware of their secret wealth. These dramas dare to ask, “Could you possibly forgive the man you’re dating when he reveals that he’s one of the richest people on the planet?” Morally, this subgenre is never quite what you expect: Rather than conveying the idea that even homeless people are real people, with dignity, the message is that you shouldn’t judge these men because they might turn out to be secretly more powerful and wealthy than you. Vertical drama billionaires are also universally outfitted with the most hilariously slapdash facial hair ever committed to screen. The men all start out looking like they’ve just walked out of Spirit Halloween so there can be a scene where he “shaves” and debuts his babyfaced perfection.

One element unites these disparate subgenres: They revolve around sex, but are sexless in execution. Even vertical dramas directly ripping off sexually explicit romantasy series remove actual sex or nudity, perhaps to get around accusations of pornography that could threaten their viability in app stores. Instead, viewers are teased by the constant insinuation of sex, or the occasional encounter that is interrupted or somehow supposed to have happened while two characters are fully clothed, and many “morning after” scenes. Shirtless men and hunks wrapped in towels dominate the proceedings, and even films in the erotica category (Swallow Me Whole, Surrender To My Professor, Submitting To My Ex’s Dad) are less sexual than a daytime soap. Bizarrely, though, there’s no such skittishness about language; even innocuous films are riddled with F-bombs.

Even when you’ve grasped the narratives’ combination of trashy and saccharine, you’ll still be entirely unprepared for how they look and sound. Vertical dramas make Ed Wood and Tommy Wiseau films look like Oscar bait. They don’t even have the infamy-generating advantage, as in the case of something like The Room or Plan 9 From Outer Space, of having been the product of a delusional artist’s singular vision. Rather, these are cynical, mass-produced products from studios that simply do not give a damn.

The most basic limitations of shooting an entire feature film vertically, for native playback on phones—composition, blocking, cinematography—are luxuries you can’t afford when you know your viewer is watching on a screen too small to make out fine details. This leads vertical dramas to focus their shots on static characters and their faces, which often end up cropped by sides of the screen anyway. Rare action scenes involve fistfights that sprawl out of the frame, leading to the audience missing half of each movement. Punches whiff their intended target by a foot or more, but are sold by the intended recipient anyway because they know there will be no second take. The same idea applies to the vertical drama philosophy around lighting, which is “no lighting.” Sets are reused repeatedly, with the same low-ceilinged office building unconvincingly doubling as everything from a fancy restaurant, to an airport terminal, to a mansion.

This absence of basic professionalism pales in comparison to the aesthetic choices wielded by the sound teams. Dialogue goes from crisp, to muffled, to echoey from scene to scene. Clearly ADR’d lines fly in out of nowhere at twice the volume of the other dialogue. Some vertical dramas are suffused with obnoxious stock music; others have no music at all, which might be worse. One mob drama, filled with gunfire and digitally added muzzle flashes, has zero gunshot sound effects. Yet, nearly every vertical drama is full of inexplicable sound effects unrelated to anything happening on screen. Every conversation is punctuated in a style that mimics obnoxious reality TV—someone finishes a sentence, then there’s a bwip like a drop of water falling into a bucket, without any indication of what that is meant to imply. Every 30 seconds or so, one of these sound effects will be employed, whether it’s a cartoony sproing, or the shwing of a kung fu movie sword slicing through the air. Rarely are they relevant. It’s like a wheel is being spun, and a soundboard is being hit at random. Their blatant, torrential misuse begins to feel like an aural hallucination, and is so omnipresent that you’ll find Reddit threads of people trying to understand what they could possibly mean.

Why does the consumer not demand better, considering the incredible expense? Are the people paying $20 a pop aware that there are actual feature films out there—many of them free to access—brimming with the genuine titillation and payoff that vertical dramas are denying them, not to mention bonuses like professional actors? How did these companies unearth such a large user base of people who like romantasy, but wish it contained no fantasy, no sex, and no action? This cognitive dissonance rears its head in the comments of vertical dramas that are uploaded in full or in parts to external sites like YouTube—people dunk on the abysmal quality, while admitting that they can’t stop watching. The addictive urge is especially present for incomplete stories: People insist that it isn’t worth paying for, while simultaneously begging for tips about where they can find it uploaded in full. It is an audience at war with itself, furtively ashamed at its own fixation.

One area where they’re united, though, springs from the form itself—a style of content that blatantly steals IP and assigns no value to originality. One of the highest-rated vertical dramas on IMDb,We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together, has somehow been below the notice of Taylor Swift’s attorneys. Yellowstone: King Of Montana is an amalgam of every Taylor Sheridan show. Many of the “mafia” dramas even steal the title font of The Godfather. It makes sense then that piracy of vertical dramas is rampant, with any given film being endlessly stolen and reuploaded in every corner of the web you could think of, and some you would never suspect. Search for Found A Homeless Billionaire Husband For Christmas on Google, and you might expect ReelShort’s original version to be a top result. Instead, you’ll stumble upon users who have uploaded the full 90-minute film everywhere else, starting witha YouTube version in the wrong aspect ratio with garbled sound, which has still amassed more than 1.5 million views. The same film can also be found uploadedin full on Dailymotion and even as a 90-minute Facebook reel on a user’s personal page. That Facebook user has uploaded countless vertical dramas in their entirety, and no one seems to notice or care. Theft is the native tongue of this subculture, baked into the experience at a foundational level, powered by the ravenous imperative to consume.

It’s fitting that the vertical drama user base has no qualms about stealing and republishing this content, when the very form itself relies on that type of thievery in order to satisfy the ravenous demand for escapist storytelling among audiences. It’s not that the drive to broad escapism is difficult to understand, but a side effect of this particularly bizarre and hyper-commercialized caricature of escape—the simple act of rotating a screen 90 degrees—has upended the traditional conception of filmmaking and birthed something hideous, exploitative, insulting, and somehow still addictive in its place.