Written by Tristan Hume, a lead on Anthropic’s performance optimization team. Tristan designed—and redesigned—the take-home test that’s helped Anthropic hire dozens of performance engineers.

Evaluating technical candidates becomes harder as AI capabilities improve. A take-home that distinguishes well between human skill levels today may be trivially solved by models tomorrow—rendering it useless for evaluation.

Since early 2024, our performance engineering team has used a take-home test where candidates optimize code for a simulated accelerator. Over 1,000 candidates have completed it, and dozens now work here, including engineers who brought up our Trainium cluster and shipped every model since Claude 3 Opus.

But each new Claude model has forced us to redesign the test. When g…

Written by Tristan Hume, a lead on Anthropic’s performance optimization team. Tristan designed—and redesigned—the take-home test that’s helped Anthropic hire dozens of performance engineers.

Evaluating technical candidates becomes harder as AI capabilities improve. A take-home that distinguishes well between human skill levels today may be trivially solved by models tomorrow—rendering it useless for evaluation.

Since early 2024, our performance engineering team has used a take-home test where candidates optimize code for a simulated accelerator. Over 1,000 candidates have completed it, and dozens now work here, including engineers who brought up our Trainium cluster and shipped every model since Claude 3 Opus.

But each new Claude model has forced us to redesign the test. When given the same time limit, Claude Opus 4 outperformed most human applicants. That still allowed us to distinguish the strongest candidates—but then Claude Opus 4.5 matched even those. Humans can still outperform models when given unlimited time, but under the constraints of the take-home test, we no longer had a way to distinguish between the output of our top candidates and our most capable model.

I’ve now iterated through three versions of our take-home in an attempt to ensure it still carries signal. Each time, I’ve learned something new about what makes evaluations robust to AI assistance and what doesn’t.

This post describes the original take-home design, how each Claude model defeated it, and the increasingly unusual approaches I’ve had to take to ensure our test stays ahead of our top model’s capabilities. While the work we do has evolved alongside our models, we still need more strong engineers—just increasingly creative ways to find them.

To that end, we’re releasing the original take-home as an open challenge, since with unlimited time the best human performance still exceeds what Claude can achieve. If you can best Opus 4.5, we’d love to hear from you—details are at the bottom of this post.

The origin of the take-home

In November 2023, we were preparing to train and launch Claude Opus 3. We’d secured new TPU and GPU clusters, our large Trainium cluster was coming, and we were spending considerably more than we had in the past on accelerators, but we didn’t have enough performance engineers for our new scale. I posted on Twitter asking people to email us, which brought in more promising candidates than we could evaluate through our standard interview pipeline, a process that consumes significant time for staff and candidates

We needed a way to evaluate candidates more efficiently. So, I took two weeks to design a take-home test that could adequately capture the demands of the role and identify the most capable applicants.

Design goals

Take-homes have a bad reputation. Usually they’re filled with generic problems which engineers find boring, and which make for poor filters. My goal was different: create something genuinely engaging that would make candidates excited to participate and allow us to capture their technical skills at a high-level of resolution.

The format also offers advantages over live interviews for evaluating performance engineering skills:

Longer time horizon: Engineers rarely face deadlines of less than an hour when coding. A 4-hour window (later reduced to 2 hours) better reflects the actual nature of the job. It’s still shorter than most real tasks, but we need to balance that with how onerous it is.

Realistic environment: No one watching or expecting narration. Candidates work in their own editor without distraction.

Time for comprehension and tooling: Performance optimization requires understanding existing systems and sometimes building debugging tools. Both are hard to realistically evaluate in a normal 50 minute interview.

Compatibility with AI assistance: Anthropic’s general candidate guidance asks candidates to complete take-homes without AI unless indicated otherwise. For this take-home, we explicitly indicate otherwise.

Longer-horizon problems are harder for AI to solve completely, so candidates can use AI tools (as they would on the job) while still needing to demonstrate their own skills.

Beyond these format-specific goals, I applied the same principles I use when designing any interview to make the take-home:

Representative of real work: The problem should give candidates a taste of what the job actually involves.

High signal: The take-home should avoid problems that hinge on a single insight and ensure candidates have many chances to show their full abilities — leaving as little as possible to chance. It should also have a wide scoring distribution,and ensure enough depth that even strong candidates don’t finish everything.

No specific domain knowledge: People with good fundamentals can learn specifics on the job. Requiring narrow expertise unnecessarily limits the candidate pool.

Fun: Fast development loops, interesting problems with depth, and room for creativity.

The simulated machine

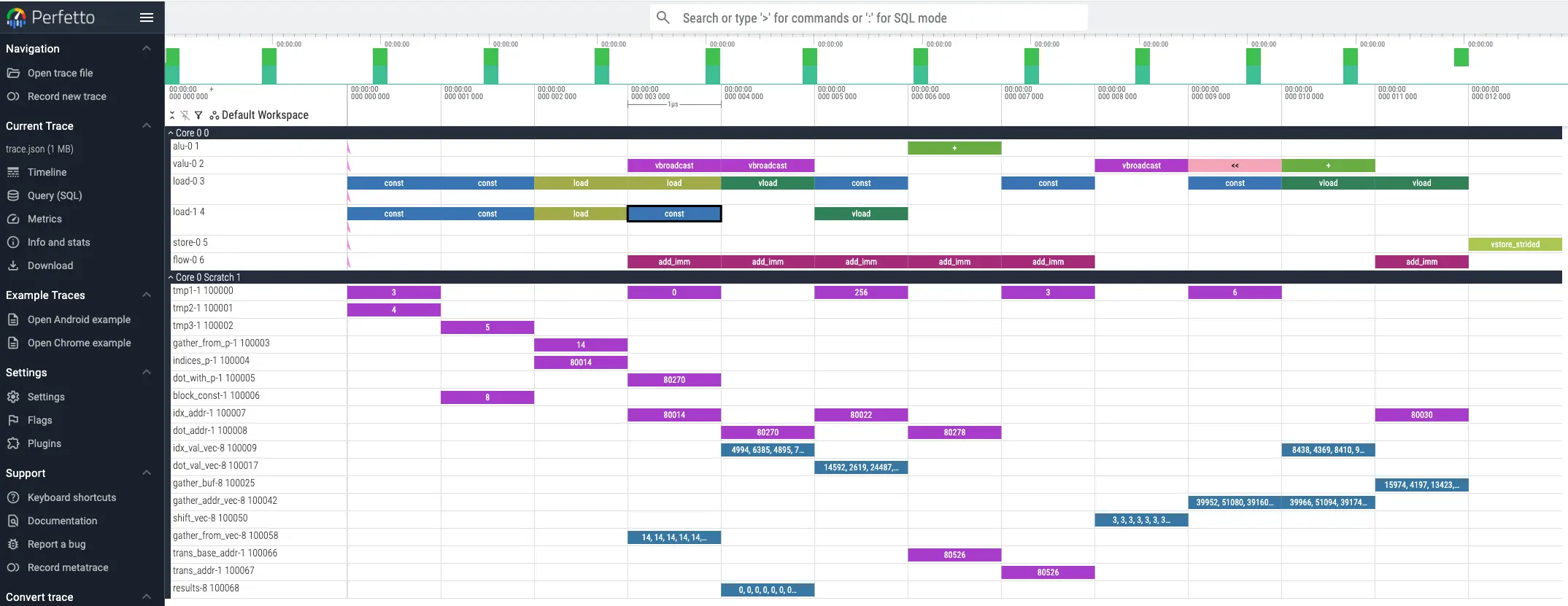

I built a Python simulator for a fake accelerator with characteristics that resemble TPUs. Candidates optimize code running on this machine, using a hot-reloading Perfetto trace that shows every instruction, similar to the tooling we have on Trainium.

The machine includes features that make accelerator optimization interesting: manually managed scratchpad memory (unlike CPUs, accelerators often require explicit memory management), VLIW (multiple execution units running in parallel each cycle, requiring efficient instruction packing), SIMD (vector operations on many elements per instruction), and multicore (distributing work across cores).

The task is a parallel tree traversal, deliberately not deep learning flavored, since most performance engineers hadn’t worked on deep learning yet and could learn domain specifics on the job. The problem was inspired by branchless SIMD decision tree inference, a classical ML optimization challenge as a nod to the past, which only a few candidates had encountered before.

Candidates start with a fully serial implementation and progressively exploit the machine’s parallelism. The warmup is multicore parallelism, then candidates choose whether to tackle SIMD vectorization or VLIW instruction packing. The original version also included a bug that candidates needed to debug first, exercising their ability to build tooling.

Early results

The initial take-home worked well. One person from the Twitter batch scored substantially higher than everyone else. He started in early February, two weeks after our first hires through the standard pipeline. The test proved predictive: He immediately began optimizing kernels and found a workaround for a launch-blocking compiler bug involving tensor indexing math overflowing 32 bits.

Over the next year and a half, about 1,000 candidates completed the take-home, and it helped us hire most of our current performance engineering team. It proved especially valuable for candidates with limited experience on paper: several of our highest-performing engineers came directly from undergrad but showed enough skill on the take-home for us to hire confidently.

Feedback was positive. Many candidates worked past the 4-hour limit because they were enjoying themselves. The strongest unlimited-time submissions included full optimizing mini-compilers and several clever optimizations I hadn’t anticipated.

Then Claude Opus 4 defeated it

By May 2025, Claude 3.7 Sonnet had already crept up to the point where over 50% of candidates would have been better off delegating to Claude Code entirely. I then tested a pre-release version of Claude Opus 4 on the take-home. It came up with a more optimized solution than almost all humans did within the 4-hour limit.

This wasn’t my first interview defeated by a Claude model. I’d designed a live interview question in 2023 specifically because our questions at the time were based around common tasks that early Claude models had lots of knowledge of and so could solve easily. I tried to design a question that required more problem solving skill than knowledge, still based on a real (but niche) problem I’d solved at work. Claude 3 Opus beat part 1 of that question; Claude 3.5 Sonnet beat part 2. We still use it because our other live questions aren’t AI-resistant either.

For the take-home, there was a straightforward fix. The problem had far more depth than anyone could explore in 4 hours, so I used Claude Opus 4 to identify where it started struggling. That became the new starting point for version 2. I wrote cleaner starter code, added new machine features for more depth, and removed multicore (which Claude had already solved, and which only slowed down development loops without adding signal).

I also shortened the time limit from 4 hours to 2 hours. I’d originally chosen 4 hours based on candidate feedback preferring less risk of getting sunk if they got stuck for a bit on a bug or confusion, but the scheduling overhead was causing multi-week delays in our pipeline. Two hours is much easier to fit into a weekend.

Version 2 emphasized clever optimization insights over debugging and code volume. It served us well—for several months.

Then Claude Opus 4.5 defeated that

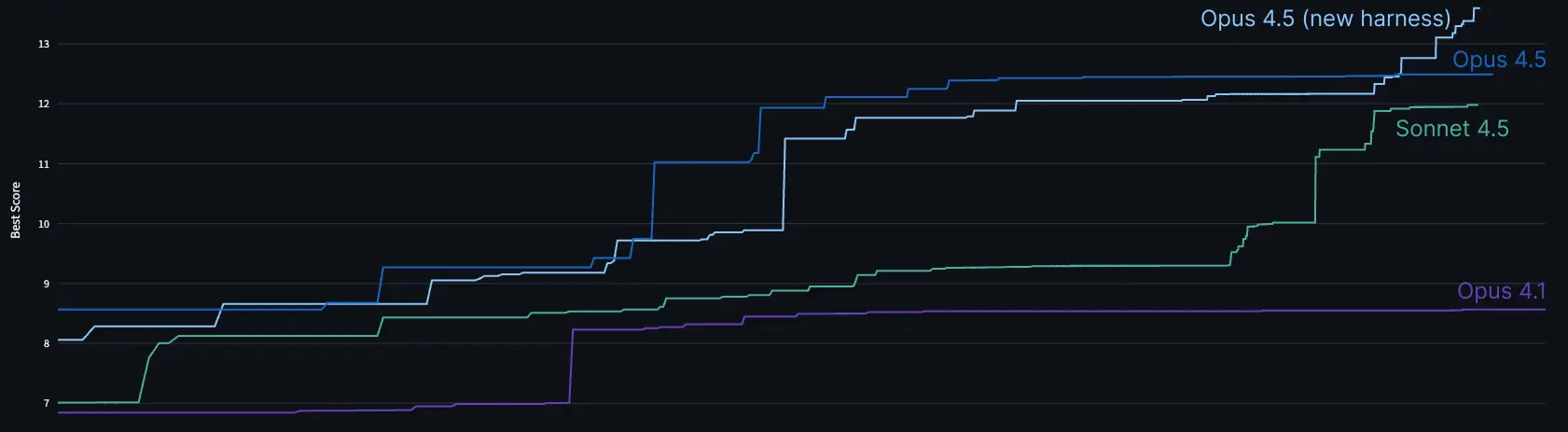

When I tested a pre-release Claude Opus 4.5 checkpoint, I watched Claude Code work on the problem for 2 hours, gradually improving its solution. It solved the initial bottlenecks, implemented all the common micro-optimizations, and met our passing threshold in under an hour.

Then it stopped, convinced it had hit an insurmountable memory bandwidth bottleneck. Most humans reach the same conclusion. But there are clever tricks that exploit the problem structure to work around that bottleneck. When I told Claude the cycle count it was possible to achieve, it thought for a while and found the trick. It then debugged, tuned, and implemented further optimizations. By the 2-hour mark, its score matched the best human performance within that time limit—and that human had made heavy use of Claude 4 with steering.

We tried it out in our internal test-time compute harness for more rigor and confirmed it could both beat humans in 2 hours and continue climbing with time. Post-launch we even improved our harness in a generic way and got a higher score.

I had a problem. We were about to release a model where the best strategy on our take-home would be delegating to Claude Code.

Considering the options

Some colleagues suggested banning AI assistance. I didn’t want to do this. Beyond the enforcement challenges, I had a sense that given people continue to play a vital role in our work, I should be able to figure out some way for them to distinguish themselves in a setting *with AI—*like they’d have on the job. I didn’t want to give in yet to the idea that humans only have an advantage on tasks longer than a few hours.

Others suggested raising the bar to "substantially outperform what Claude Code achieves alone." The concern here was that Claude works fast. Humans typically spend half the 2 hours reading and understanding the problem before they start optimizing. A human trying to steer Claude would likely be constantly behind, understanding what Claude did only after the fact. The dominant strategy might become sitting back and watching.

Nowadays performance engineers at Anthropic still have lots of work to do, but it looks more like tough debugging, systems design, performance analysis, figuring out how to verify the correctness of our systems, and figuring out how to make Claude’s code simpler and more elegant. Unfortunately these things are tough to test in an objective way without a lot of time or common context. It’s always been hard to design interviews that represent the job, but now it’s harder than ever.

But I also worried if I invested in designing a new take-home, either Claude Opus 4.5 would solve that too, or it would become so challenging that it would be impossible for humans to complete in two hours.

Attempt 1: A different optimization problem

I realized Claude could help me implement whatever I designed quickly, which motivated me to try developing a harder take-home. I chose a problem based on one of the trickier kernel optimizations I’d done at Anthropic: an efficient data transposition on 2D TPU registers while avoiding bank conflicts. I distilled it into a simpler problem on a simulated machine and had Claude implement the changes in under a day.

Claude Opus 4.5 found a great optimization I hadn’t even thought of. Through careful analysis, it realized it could transpose the entire computation rather than figuring out how to transpose the data, and it rewrote the whole program accordingly.

In my real case, this wouldn’t have worked, so I patched the problem to remove that approach. Claude then made progress but couldn’t find the most efficient solution. It seemed like I had my new problem, now I just had to hope human candidates could get it fast enough. But I had some nagging doubt, so I double-checked using Claude Code’s "ultrathink" feature with longer thinking budgets ... and it solved it. It even knew the tricks for fixing bank conflicts.

In hindsight, this wasn’t the right problem to try. Engineers across many platforms have struggled with data transposition and bank conflicts, so Claude has substantial training data to draw on. While I’d found my solution from first principles, Claude could draw on a larger toolbox of experience.

Attempt 2: Going weirder

I needed a problem where human reasoning could win over Claude’s larger experience base: something sufficiently out of distribution. Unfortunately, this conflicted with my goal of being recognizably like the job.

I thought about the most unusual optimization problems I’d enjoyed and landed on Zachtronics games. These programming puzzle games use unusual, highly constrained instruction sets that force you to program in unconventional ways. For example, in Shenzhen I/O, programs are split across multiple communicating chips that each hold only about 10 instructions with one or two state registers. Clever optimization often involves encoding state into the instruction pointer or branch flags.

I designed a new take-home consisting of puzzles using a tiny, heavily constrained instruction set, optimizing solutions for minimal instruction count. I implemented one medium-hard puzzle and tested it on Claude Opus 4.5. It failed. I filled out more puzzles and had colleagues verify that people less steeped in the problem than me could still outperform Claude.

Unlike Zachtronics games, I intentionally provided no visualization or debugging tools. The starter code only checks whether solutions are valid. Building debugging tools is part of what’s being tested: you can either insert well-crafted print statements or ask a coding model to generate an interactive debugger in a few minutes. Judgment about how to invest in tooling is part of the signal.

I’m reasonably happy with the new take-home. It might have lower variance than the original because it comprises more independent sub-problems. Early results are promising: scores correlate well with the caliber of candidates’ past work, and one of my most capable colleagues scored higher than any candidate so far.

I’m still sad to have given up the realism and varied depth of the original. But realism may be a luxury we no longer have. The original worked because it resembled real work. The replacement works because it simulates novel work.

An open challenge

We’re releasing the original take-home for anyone to try with unlimited time. Human experts retain an advantage over current models at sufficiently long time horizons. The fastest human solution ever submitted substantially exceeds what Claude has achieved even with extensive test-time compute.

The released version starts from scratch (like version 1) but uses version 2’s instruction set and single-core design, so cycle counts are comparable to version 2.

Performance benchmarks (measured in clock cycles from the simulated machine):

- 2164 cycles: Claude Opus 4 after many hours in the test-time compute harness

- 1790 cycles: Claude Opus 4.5 in a casual Claude Code session, approximately matching the best human performance in 2 hours

- 1579 cycles: Claude Opus 4.5 after 2 hours in our test-time compute harness

- 1548 cycles: Claude Sonnet 4.5 after many more than 2 hours of test-time compute

- 1487 cycles: Claude Opus 4.5 after 11.5 hours in the harness

- 1363 cycles: Claude Opus 4.5 in an improved test time compute harness after many hours

Download it on GitHub. If you optimize below 1487 cycles, beating Claude’s best performance at launch, email us at performance-recruiting@anthropic.com with your code and a resume.

Or you can apply through our typical process, which uses our (now) Claude-resistant take-home. We’re curious how long it lasts.