by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

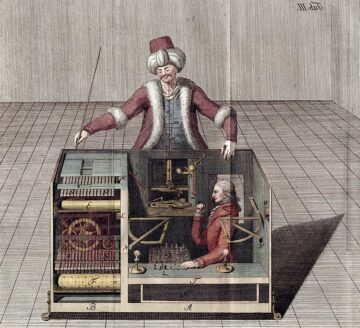

Source: The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker. via Wikipedia

Source: The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker. via Wikipedia

Artificial intelligence is generally conceptualized as a new technology which goes back only decades. In the popular imagination, at best we stretch it back to the Dartmouth Conference in 1956 or perhaps the birth of the Artificial Neurons a decade prior. Yet the impulse to imagine, build, and even worry over artificial minds has a long history. Long before they could build one, civilizations across the world built automata, thought about machines that could mimicked intelligence, and thought about the philosophical consequences of ar…

by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

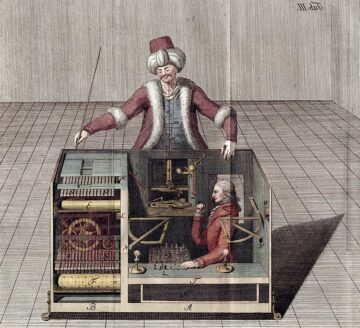

Source: The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker. via Wikipedia

Source: The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker. via Wikipedia

Artificial intelligence is generally conceptualized as a new technology which goes back only decades. In the popular imagination, at best we stretch it back to the Dartmouth Conference in 1956 or perhaps the birth of the Artificial Neurons a decade prior. Yet the impulse to imagine, build, and even worry over artificial minds has a long history. Long before they could build one, civilizations across the world built automata, thought about machines that could mimicked intelligence, and thought about the philosophical consequences of artificial thought. One can even think of AI as an old technology. That does not mean that we deny its current novelty but rather we recognize its deep roots in global history. One of the earliest speculations on machines that act like people. In Homer’s Iliad, the god Hephaestus fashions golden attendants who walk, speak, and assist him at his forge. Heron of Alexandria, working in the first century CE, designed elaborate automata that were far ahead of their time: self-moving theaters, coin-operated dispensers, and hydraulic birds.

Aristotle even speculated that if tools could work by themselves, masters would have no need of slaves. In the medieval Islamic world, the Musa brothers’ Book of Ingenious Devices (9th century) described the first programmable machines. Two centuries later, al-Jazari built water clocks, mechanical musicians, and even a programmed automaton boat, where pegs on a rotating drum controlled the rhythm of drummers and flautists. In ancient China we observe one of the oldest legends of mechanical beings, the Liezi (3rd century BCE) recounts how the artificer Yan Shi presented a King with a humanoid automaton capable of singing and moving. Later, in the 11th century, Su Song built an enormous astronomical clock tower with mechanical figurines that chimed the hours. In Japan, karakuri ningyo, intricate mechanical dolls of the 17th–19th centuries, were able to perform tea-serving, archery, and stage dramas. In short, the phenomenon of precursors of AI are observed globally.

In medieval and Renaissance Europe, a parallel tradition of mechanizing thought emerged through the scholastic and logical projects of thinkers like Ramon Llull, Leibniz. Llull’s Ars Magna (13th century) proposed a device of rotating wheels inscribed with divine and philosophical concepts, allowing users to generate combinations and deduce theological truths. His goal was both missionary and logical i.e., to show that reason could systematically uncover metaphysical truths. Centuries later, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, envisioned a Calculus Ratiocinator and a universal language of reasoning where disputes could be settled by computation. “Let us calculate,” he famously declared. These efforts represent early attempts to formalize logic as a manipulable system, transforming thought into mechanical procedure.

One can argue that ancient automata gave us artificial bodies, and ancient philosophy gave us artificial minds. Aristotle pondered an important question, could reasoning itself be formalized into rules? One of the most interesting Islamicate precedent for language models is the Zairja, a device described by Ibn Khaldun. The Zairja used tables of Arabic letters to generate new ideas through systematic combination. Its practitioners claimed that, by following its rules, they could derive answers to almost any question. In many ways, the Zairja can be seen as a spiritual and intellectual ancestor of today’s large language models. Both operate on the principle that meaning can emerge from systematic recombination of symbols. Where the Zairja’s practitioners believed divine knowledge could be accessed through the patterned play of language, modern AI researchers train vast models to uncover statistical regularities across texts. In a way it sought to mechanize thought through combinatorial logic. The Zairja was not a computer in the modern sense, but it foreshadowed some aspects of language models e.g., cognition as symbol manipulation, knowledge as rule-bound procedure. It also carried a spiritual aspect, in Sufi cosmology, letters were thought to encode divine truths. To recombine them was to probe hidden structures of creation. Various systems of logic, whether its Greek, Indian or Chinese could be said to codify inference into rigorous syllogisms.

If philosophy formalized reasoning, literature explored its consequences. Stories about artificial beings reveal the hopes and terrors of living with intelligent doubles. Western traditions gave us the myth of Pygmalion, who fell in love with his statue, and Ovid’s tales of moving statues and enchanted beings. Later, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein became the paradigmatic story of artificial creation gone awry, and Karel Capek’s R.U.R. (1921) gave us the word the word “robot.” The Arabic One Thousand and One Nights contains tales of mechanical horses, flying automata, and enchanted yet engineered beings. Indian epics like the Mahabharata speak of divine weapons activated by mantras, coded instructions with set rules. These stories are not isolated examples but rather human speculation n the possibility of human creations hat may imitate us

It is important to remind ourselves of these precedents, it changes how we see the present. The narrative of AI as a sudden Western invention, birthed in the mid-20th century from Turing and von Neumann, is true but only part of the story. It erases the global genealogy of artificial minds and blinds us to how deep the cultural roots of AI run. Recognizing the Zairja reminds us of speculations on systems like language models. More importantly, these precedents sharpen today’s debates. When Ibn Khaldun warned that the Zairja gave “idle thinkers an occupation” but not true knowledge, he might as well have been diagnosing the kind of problems that we encounter with large language models. When Mary Shelley tells us about Frankenstein’s monster demanding recognition, she anticipated today’s concerns about AI alignment and autonomy. Across time and cultures, the same anxieties repeat: will our artificial creations serve us, deceive us, or surpass us?

To summarize, Artificial intelligence is not new. From Homer’s golden servants to al-Jazari’s drummers, from the Zairja to [Llull’s combinatorial wheels](http://Llull’s combinatorial wheels), from karakuri dolls to Shelley’s monster, humans have long tested the boundary between the natural and the artificial. What we call AI today, statistical models trained on massive amounts of data, is technologically novel, but imaginatively ancient. Once we understand AI as an old technology, we gain perspective. We see that our ancestors across civilizations were already grappling with these questions. Their stories, devices, and philosophies remain a resource for us. They remind us that artificial intelligence is not only a matter of code, but of culture. Perhaps it represents an enduring human desire to create minds beyond our own.