by Kevin Lively

Pieter Brueghel the Younger “Summer: The Harvesters”, 1623.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger “Summer: The Harvesters”, 1623.

One often used metric by which the ‘complexity’ of societies is judged, is the level of logistic sophistication with which they self-propagate. While the engineering and logistical nuances of how modern society sustains itself are the fodder for endless analysis; equally complex is the almost-unconscious cultural framework within which this takes place.

One primary foundation of our cultural framework is how we perceive and construct The Commons; that is,…

by Kevin Lively

Pieter Brueghel the Younger “Summer: The Harvesters”, 1623.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger “Summer: The Harvesters”, 1623.

One often used metric by which the ‘complexity’ of societies is judged, is the level of logistic sophistication with which they self-propagate. While the engineering and logistical nuances of how modern society sustains itself are the fodder for endless analysis; equally complex is the almost-unconscious cultural framework within which this takes place.

One primary foundation of our cultural framework is how we perceive and construct The Commons; that is, lands or resources whose usufruct are held in some degree of common ownership. Historical examples include who may, and may not, take fish from the streams and oceans; who may, and may not, take firewood and game from the forest; who may, and may not, access pastureland for grazing animals, and so on.

For a modern city dweller, these examples are functionally abstractions. More pertinent would be, for example, the quality of air and water, access to public libraries, public transportation and medical care, or food banks and homeless shelters. These are of course common-pool resources as everyone has both rights to their access and responsibilities for their upkeep. The structure of our societies is such that when you’re wealthy, availability of The Commons is of negligible benefit. However, when your private command over resources is limited, i.e. you’re broke, the “cultural-infrastructure” determining which level of access to which resources is permissible, may set the entire course of your life. More than that, the ramifications of socially mediated access of individuals to natural resources, multiplied out across entire societies, can drive the evolution of entire cultures.

From Sheep to Steel

The Commons are a familiar starting point for students of modernity, as they are often argued to be the progenitor of of early capitalism and the subsequent industrial revolution. More precisely, it is the *enclosure *of the commons which graces the opening chapters of many textbooks on the industrialization and economics. The story usually goes like something as follows.

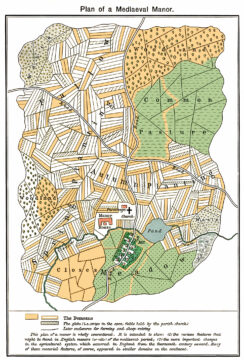

Exemplary plan for a medieval manor.

Exemplary plan for a medieval manor.

In the feudal open-field system of England, a share of the land held by the lords was subject to some form of collective cultivation, usually conditional on a return of a share of the harvest to the landlord. While feudal rights were notoriously complex and location specific, in broad strokes these included (1) common grazing for otherwise privately tended fields which were fallow or already harvested, (2) grazing on the common meadow, and (3) “waste” land otherwise unsuitable for orderly plow-strips. Only certain groups of people, the Commoners — which were not necessarily everyone in the vicinity — would have the right of access to these different lands which was crucially joined with complex overlapping sets of responsibilities.

Enclosed land, by contrast, generally had no common usufruct at any time, thus allowing for more of the grain harvested or wool shorn to go to market, rather than be shared out. Enclosure is then the process of removing common rights from a parcel of land. Oftentimes this was done by purchase, and thus common rights holders were often initially enthusiastic. Enclosure proceeded sporadically throughout the late-medieval and early modern period until Parliament made the process more systematic between 1700-1850. By some estimates, around 1600 about 27% of land in England was had common rights, while by 1900 “virtually all of England was under private consolidated ownership“.

The precise effects, vis-a-vis productivity of the land and effects on population in highly enclosed areas have been widely debated: see previous links and this one. Nonetheless, for the purposes of the story the argument goes that once this process accelerated in the 18th century, the virtual elimination of the rural Commons shifted the structure of society in numerous ways. Common-right holders now became hired laborers. Their new bosses, sometimes themselves peasants, then had to take loans in order to advance these wages, mortgaging their land as collateral and adding sophistication to the financial system. This financial system could then invest in new enterprises. Some of these enterprises took the form of factories in burgeoning mill towns, thus leading a migration of redundant and landless rural laborers to become the cogs of industry.

An important historiographical side-note; this is when the “Tragedy of the Commons”, as we now understand it, begins to emerge. By the 1830s, once most of the prime lands had been privatized the economic writer William Forster Lloyd published a pamphlet declaring that the Commons are naturally subject to degradation due to rampant over-exploitation. This point was raised in Garrett Hardin’s 1968 article which coined the phrase “Tragedy of the Commons”, making the notion common-place. However, these articles neglected the sophisticated rules of access involved in defining common-rights, and decades of detailed empirical research, for example that of Nobel prize winner Elinor Ostrom, has revealed numerous examples where resources can be managed sustainably.

Now, every link in the above narrative chain is subject to rigorous debate. However, for the sake of argument, let us accept the above story as true. In this reasoning then, the principle impulse which drove England from the early modern to the industrial period was a slow change in the cultural structure connecting individuals to the environment. Specifically, this structure was the cultural construct of The Commons and thus the rights of individuals to access natural resources for their survival. It appears then that analyzing modern cultural frameworks of common-rights would be crucial to understand how we can shape the future structure of our own society.

The “Environment” and the Individual

In order to develop a framework for analyzing emergent behavior like the evolution of human cultures, we must first observe that the selection pressures which individuals, and thus societies, are subject to are not solely, or even predominantly, a result of the land they live on. Obviously there are physical and “natural” environmental selection pressures on individuals, perhaps most prominently disease susceptibility and local resource availability. However in terms of actually acquiring and processing resources for survival, while individuals can exist for brief stretches in isolation, humans of course require other humans to survive. Thus, in many circumstances, it is probably just as accurate to say that the evolutionary environment is the broader material and social culture in which individuals are embedded.

This is especially true in (post-)industrialized societies. If your hands have never, or only ever rarely, held a plow or skinned a rabbit and you’ve never had smallpox, it is your society, and not the farmland, forest or oceans it ultimately relies on, which constitutes the principle environment in which you live. The relatively recent enlightenment of germ theory, widespread availability of vaccines, functional medical intervention and plentiful food, water and shelter, constitute a sharp discontinuity in our evolutionary history, and none of them were induced by physical changes in the environment. On the contrary of course, the subsequent exponential explosion of humanity in the last ~150 years has converted about 96% of the total mammalian biomass into humans or food for humans, and begun seemingly uncontrollable alteration of the atmosphere and oceans.

Now some variant of the argument that the material conditions of a society, specifically the distribution of access to resources, determines its historical evolution is often given in the materialist tradition of historiography and social studies. In extremis this can manifest as the notion that humans are a blank slate, merely the product of the sum of societal and material forces upon them and thus imminently moldable like a clay vessel. Detractors from this materialist perspective will assert some inalienable intrinsic character, inherent at the biological or physical level of individuals, out of which cultural factors inexorably arise. This nature-versus-nurture question is of course the source of endless debate across philosophy, psychology and biology.

Perhaps more traction can be gained by reframing these seemingly opposed positions in terms of the principle of emergence from many-body systems. In a nutshell this is the natural process by which a system of many components interacting according to a fixed set of rules result in a collective whose behavior is fundamentally different than the components themselves. That is to say, just as the phenomenology of an ant-colony is fundamentally distinct from the behavior of individual ants, so is the phenomenology of human society fundamentally distinct from the behavior of an individual human being.

However for humans, the complication is that the emergence occurs on both ends of the scale: the interaction rules are set by the culture but bent by the individual, while the culture emerges from the interactions and elevates individuals to become its exemplars. Where this loop breaks, is in how the culture interacts with the external physical environment in order to self-propagate, and it is exactly at this meeting point where The Commons lie.

Common Survival

If we want to avoid going back to a (potentially radioactive) feudal-like resource management system, then we need to take a good look at how we regulate access to our modern commons. Again, lets take these to include affordable shelter and utilities, functional public transportation, addiction rehabilitation and medical care. Normally in political discourse it’s at this point that discussion would instantly collapse into determining which points along the state controlled to private-market controlled spectrum is the most moral or efficient for each of these points. However, this is likely a collective limitation in imagination induced by the last century of propaganda wars between competing power centers on that spectrum.

The recent form of Byzantine like bureaucratized liberalism is fundamentally ill-equipped to build the necessary energy and housing infrastructure to move away from our current destructive lifestyle, while being too captured by corporate interests to provide meaningful healthcare reform. Conversely an authoritarian police state which directs the full breadth of it’s internal security forces to root out dissent, as is very directly written in the recent National Security Presidential Memorandum 7, is hardly conducive to collective political action which goes against its corporate backers.

Instead, perhaps we should look more to the rich panoply of human endeavors across time for an understanding of how expert knowledge and local collective decision making can co-exist in various forms. In Elinor Ostrom’s work for example she finds that many sustainable common-pool resource management systems involve social relations which bear no resemblance to markets or states. The work of James C. Scott details various centralizing, hierarchical and hegemonic projects — applied to states but just as easily applied to corporations — showing that the attempt to reduce local conditions to legible forms for distant bureaucrats often sabotages the very attempts to improve them.

In more practical terms, this means contributing to a local politics which can generate functional public services may be the first and best option to prevent greater and greater segments of American society from continuing to spiral into immiseration, and therefore perhaps to prevent a free and democratic manifestation of our culture from dying out.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.