by Marie Snyder

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear w…

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear w…

by Marie Snyder

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear witness to, or experience, absolute atrocities.

It feels like I understand the idea that all suffering comes from expectation in a way I didn’t used to. Now it seems so obvious, but I’m not really sure what flip was switched. It’s not just that if we stop expecting to get things, we’ll be happier, but how ridiculous it is to expect anything to stay the same at all, much less get better, ever. And that understanding seems to help reduce some anxiety over the things that can’t be easily changed. Suffering is inevitable, but it can be somewhat diminished in order to have more contentment. We can change what counts as suffering, and we can change our perspective around tragedies, so maybe we can also change how we can continue to bear witness to, or experience, absolute atrocities.

One simple way to reduce suffering is to narrow the definition. Comedian Michelle Wolf jokes, “It’s hard to have a struggle and a skin care routine,” which clarifies that we might be considering some difficulties as suffering in a way that doesn’t fly when we widen the scope of our horizons. Pain is pain and can’t definitively be compared, yet I believe many of us have an automatic judgment in our heads that lists events in a hierarchy. Typically suffering from having to do a task we don’t want to do, like write a boring report or clean out the fridge, or from wanting luxuries we can’t afford, like another trip, might be relegated to the bottom as whining. The pain from it is there, though: the agony and stress from uninteresting maintenance that’s necessary to further our own existence or the grief over lost opportunities. Furthermore, it can develop an extra layer of shame on top of the suffering if we try and fail to elicit sympathy for having so much food that some is left to rot and needs to be cleaned. When we realize we can’t afford that trip after all, this is a suffering we are expected to bear without complaint.

The shame on top of the very real distress doesn’t help, but a different perspective might: comparing to those worse off, recognizing the tasks as merely one choice with alternatives that are even less pleasant, or maybe even finding ways to enjoy the task or staycation are ideas passed down for millenia. If we can increase our distress tolerance around these lesser calamities, then we can potentially wipe out the bottom layer of our pile of pain.

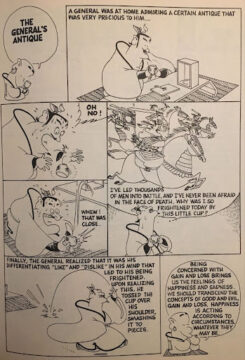

It might also help to recognize how much unnecessary suffering is created from clinging to capitalist expectations of perpetual progress. We think we should constantly improve and have more and more, but, of course, there are limits to all things, including ourselves. I’ve watched our schools shift over the last 30 years from messages about doing your best work to insisting kids should be reaching for the stars and finding their *true passion, *a provocation that inevitably leads to disappointment. The fact that we can’t have all the things we want is great news if we can accept our interdependency with others or cultivate a sense of enoughness by accepting our limits. The shame can add to the problem, but it can sometimes help us laugh at our own childishness if we realize our pain is because we wanted a thing that we just couldn’t have. We wish we were faster or smarter or prettier or tidier. Things often don’t work out the way we hoped, and that’s okay.

Carl Jung spoke to this childishness:

“The greatest and most important problems of life are all in a certain sense insoluble. . . . They can never be solved, but only outgrown. . . . This “outgrowing,” as I formerly called it, on further experience was seen to consist in a new level of consciousness. Some higher or wider interest arose on the person’s horizon, and through this widening of view, the insoluble problem lost its urgency. It was not solved logically in its own terms, but faded out when confronted with a new and stronger life-tendency.”

And Nietzsche advised to think before we react to a misfortune:

”One must not respond immediately to a stimulus; one must acquire a command of the obstructing and isolating instincts. . . . All lack of intellectuality, all vulgarity, arises out of the inability to resist a stimulus: — one must respond or react, every impulse is indulged.”

Of course the Stoics were all about this. Health, long life, reputation, a nice home and good food, and the company of people we love are preferences mostly out of our control, much as we try to control them. They’re our preferred indifferents. It’s wise to make efforts to influence them through wise choices, but it’s foolish to expect them. The Stoic goal is mastering perception to see these things correctly, but it’s striking how difficult it is to overcome a desire to get our way despite being constantly batted around by life. We suffer from others. Epictetus has advice for the taking an insult in the Enchiridion:

“When any person harms you, or speaks badly of you, remember that he acts or speaks from a supposition of its being his duty. Now, it is not possible that he should follow what appears right to you, but what appears so to himself. Therefore, if he judges from a wrong appearance, he is the person hurt, since he too is the person deceived. For if anyone should suppose a true proposition to be false, the proposition is not hurt, but he who is deceived about it. Setting out, then, from these principles, you will meekly bear a person who reviles you, for you will say upon every occasion, ‘It seemed so to him.’”

In Meditations, Book II, Marcus Aurelius echoes this sentiment:

“Remember to put yourself in mind every morning, that before night it will be your luck to meet with some busy-body, with some ungrateful, abusive fellow, with some knavish, envious, or unsociable churl or other. Now all this perverseness in them proceeds from their ignorance of good and evil.”

We are likely much nicer and not going about insulting others or being a churl of course Despite having some nasty thoughts swirling in mind, we don’t actually say them. (Where’s our parade??) But, those very thoughts in our head are judgments of others, which, according to Jung, often mirror self-judgments. When we’re outwardly congratulatory, but inwardly seething at the success of others, we’re suffering from our own expectations of somehow being better than that other guy. The silly part is that we don’t have to be. We could just see the achievement as a factual event rather than ascribe meaning to it. It’s difficult but possible, and it could make us less miserable.

If we can master accepting what’s beyond our control, then we can reduce suffering by eliminating the unreasonable expectation of things staying the same or getting better. It’s an attitude that’s the antithesis of our achievement society’s presumption of a continuous upward trajectory. We can’t always win them all, yet we’re curiously flabbergasted when we don’t.

We can practice this attitude with negative mediations: premeditatio malorum as described in Epictetus’s Enchiridion:

“If you are going to bathe [in the public baths], place before yourself what happens in the bath; some splashing the water, others pushing against one another, others abusing one another, and some stealing; and thus with more safety you will undertake the matter, if you say to yourself, I now intend to bathe, and to maintain my will in a manner conformable to nature. And so you will do in every act.”

Prepare for the worst not just by steeling yourself to other people’s potential shenanigans, but by mentally practicing your attitude and honourable actions in the face of difficulties. The premise is that our beliefs and expectations that cause suffering have to be acknowledged before they can be diminished, like thinking we shouldn’t have to tolerate being splashed.

Moving up that imagined hierarchy, however, can even more tragic suffering be mitigated with just a perspective shift? The idea of suffering being a matter of attitude starts to feel heartless when we’re watching devastating clips in the news. I want to be disturbed every time, fearing any sign of desensitization. But then I still have to clean the fridge.

If we spend some time each day imagining the worst, and being prepared to cope with it, then we can be better able to manage when the time comes. The goal is accepting that the worst might happen today, from irritating people to bloody battles. It’s seen in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy’s exercise of “Cope Ahead Skill“: consider how we might prepare for the worst to reduce stress in advance. Stoics also perceive losses as giving back. Everything we have, our things, our loved ones, our working eyes, ears and limbs, and our very selves, are all here temporarily.

If we stop expecting all of it to continue, it might be easier to bear. Seneca says the unexpected nature of misfortune “adds to the weight of a disaster.” We might consider it morbid or depressive to consider what could go wrong; however, it’s not to dwell on it or ruminate, but to take a limited time each day to ensure we’re not taken by surprise by the inevitable. We must particularly remember death: *memento mori. *In his letters, he writes,

“‘Rehearse death.’ To say this is to tell a person to rehearse his freedom. A person who has learned how to die has unlearned how to be a slave. He is above, or at any rate beyond the reach of, all political powers. What are prisons, warders, bars to him? He has an open door. There is but one chain holding us in fetters, and that is our love of life. There is no need to cast this love out altogether, but it does need to be lessened somewhat so that, in the event of circumstances ever demanding this, nothing may stand in the way of our being prepared to do at once what we must do at some time or other. … We need to envisage every possibility and to strengthen the spirit to deal with the things which may conceivably come about. Rehearse them in your mind: exile, torture, war, shipwreck.”

Buddhism has similar meditations. In the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10), we’re asked to contemplate the disgusting nature of our body’s parts, one at a time, and then our skeleton piled up, decayed, and reduced to powder in order to reduce clinging to anything in this world. All suffering is because we’re so attached to things as they are and to potential good fortune and we’re so averse to anything going wrong that we miss the present moments that make up our actual lives.

Before sitting with our bones turning to dust, though, we can practice with small objects: imagine losing a favourite cup and making peace with that. Then your grandmother’s china passed down to you. Then your mom. Then your partner. Then yourself.

But it’s still hard to do.

Since his recent death, Robert Redford interviews have been everywhere. At 65 he said of aging,

“You suddenly realize you have to start being careful, and I find that hard to deal with. You have to give up certain things you had when you were young, you didn’t have to think about, and suddenly you do, and that creates a restriction of some kind, and that’s kind of sad.”

I’ve had sudden changes affecting my physical capabilities that have thrown me for a loop because I had a silly expectation that my body would continue to function as it has been until one night, always in the far away distance, I gently die in my sleep, blithely oblivious to illness, aging, or death. It can seem like having that privileged illusion keeps us happier, and what’s so great about being grounded in reality anyway! But the denial of our limitations not only slams us with an eventual and jarring truth; it can also prevent connection with others. Forum boards for people with disabilities and chronic illness are rife with stories of friends and family slowly disappearing from their lives. Fear of suffering can provoke us to be callous and indifferent to pain in the worst ways. By contrast, courageous awareness of suffering can provoke compassion.

The Stoics have a concept similar to mindfulness, prosochē: an ongoing awareness of our inner disposition as well as acting in accordance with virtues. This similar skill is encouraged in Buddhism, but also in the book of changes that influence both Taoism and Confucianism: I Ching. Pay attention to what you’re thinking and feeling in order to develop and hold the right attitude in order to cultivate the right action in the moment. Managing suffering requires the right attitude, which can only be encouraged with inner awareness. In psychology we might urge people to notice and attend to defense mechanisms, like projections, and in existential philosophy, we’re cautioned to avoid bad faith, all the lies we tell ourselves about ourselves. It all starts with noticing.

It’s easier to be mindfully attuned to our attitudes when we’re around others working on the same practice on a meditation retreat, for instance. It’s harder when we’re bombarded with ads and clickbait and others also asking if we’ve seen the latest thing. However, we’re *really *not practiced on acting well amid adversity. As things get more difficult around us, we cling to what we’ve got. We double down on our current number of vacations and our right to buy everything we can afford or to the limits of our credit. People in power are allowing adults and children to be harmed, if not directly causing their intentional destruction, and it is so hard to see. When our cities feel more dangerous, it can send us into survival mode, hyperaware of potential harm, and no longer attentive to how aligned we are with our values. That’s what makes kindness in the harshest times so heroic. It’s a difficult internal battle. We don’t know if we’re up to the task until we’re in it.

Sometimes we work hard to fix ourselves through* control *over cravings, which can just add another layer of striving to overcome. The needed attitude appears to be more of a surrender, which involves removing the idea of suffering from our typical dualistic thinking as something to avoid. It’s part of life that is rooted in our attachments and our failure to fully accept that life is impermanent and constantly changing. This is more true than even for many of us as we’re existing under the threats of so much violence on top of climate change and unfettered AI. When so much feels out of control, the natural instinct is to reel it in, but that’s like trying to cage a tornado. Trying to fight the injustices just keeps us angry, and we can quickly lose hope if we don’t make a dent in this triple-headed Goliath. An alternative stance is to focus on our actions in the moment, trying to do the right thing at each step despite our limited knowledge or control, but as virtuously as possible, with compassion, courage, and thoughtfulness. If we’re helpless to stop evil, we can at least add something good to the world.

This isn’t a cold or callous exercise, nor is it an excuse for complacency. There is still a place for accepting the grief and impotent rage that wells up from time to time. The deepest suffering for me is watching children in pain and having zero to minimal ability to affect their plight besides making my voice heard on petitions, which staves a sense of powerlessness just a bit. Closely related is watching others make unfathomable decisions that will clearly harm people. It’s not just that they harm, but that we can helplessly foresee the damage about to happen. We can only take another step, making the best choices we can with the skills and resources we can access, always aware of our devastating limitations *and *open to the beauty of the world.

From Marcus Aurelius:

“What is it that troubles you? Is it the wickedness of the world? If this be your case, out with your antidote, and consider that rational beings were made for mutual advantage, that forbearance is one part of justice, and that people misbehave themselves against their will. Consider, likewise, how many men have embroiled themselves, and spent their days in disputes, suspicion, and animosities; and now they are dead, and burnt to ashes. Be quiet, then, and disturb yourself no more. … Your way is therefore to manage this minute in harmony with nature, and part with it cheerfully.”

Something like that.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.