by Herbert Harris

Sixty-five years ago this month, the John Coltrane Quartet entered Atlantic Studios in Manhattan for three days of recording sessions, over the course of a week. It was the first time the band recorded together. The four musicians — Coltrane on tenor and soprano saxophones, McCoy Tyner on piano, Steve Davis on bass and Elvin Jones on drums — remarkably produced enough material for three albums, and then some, in those three sessions. Some of the recordings are jazz classics — “Equinox,” for example, a Coltrane blues composition. Others include beautiful renditions of standards like “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” “Summertime,” and “But Not for Me…

by Herbert Harris

Sixty-five years ago this month, the John Coltrane Quartet entered Atlantic Studios in Manhattan for three days of recording sessions, over the course of a week. It was the first time the band recorded together. The four musicians — Coltrane on tenor and soprano saxophones, McCoy Tyner on piano, Steve Davis on bass and Elvin Jones on drums — remarkably produced enough material for three albums, and then some, in those three sessions. Some of the recordings are jazz classics — “Equinox,” for example, a Coltrane blues composition. Others include beautiful renditions of standards like “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” “Summertime,” and “But Not for Me.”

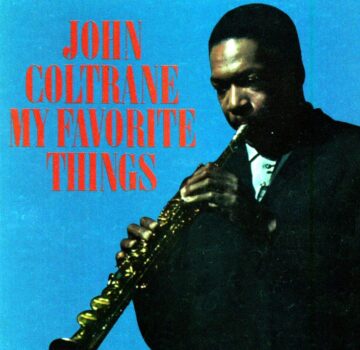

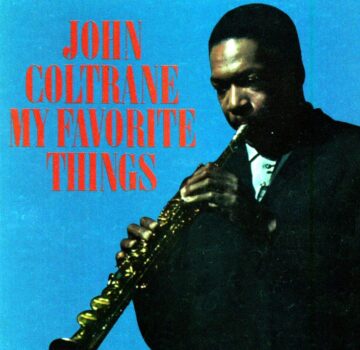

These three sessions involved intense, concentrated work by musicians at the top of their game. But in just the second song they recorded, on the first day, lightning struck in one take. On Friday afternoon, October 21, 1960 these four men recorded “My Favorite Things” — 13 minutes, 46 seconds of pure transcendence.**My Favorite Things (Stereo) (2022 Remaster)

I don’t know how many times I’ve listened to this recording, but it’s got to be hundreds. And after having listened to it so many times, I still can’t describe it in any way that really does it justice. It’s just ineffable.

Most people associate the song with Julie Andrews. She sang it in the movie version of “The Sound of Music.” My Favorite Things from The Sound of Music (Official HD Video) But that movie only came out in 1965. “The Sound of Music” started out, of course, as a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. It was based on the story of the real-life von Trapp family, as described in the 1949 memoir of its matriarch, Maria Von Trapp. It was first performed on Broadway in November 1959, with Mary Martin as Maria.

In October 1960, then, and even in March of 1961 when the recording was released, “My Favorite Things” was not the chestnut it is today. But Coltrane decided to try it. The version the quartet recorded is entirely different from the original cast recording sung by Mary Martin, or the later movie version by Julie Andrews, both of which are prim and perky.

Coltrane’s version starts with a four-bar piano introduction, played twice. The famous opening line of the song in E minor, played as E-B-F#-E-B-E-F#-E (“Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens”), is inverted to B-E-B-A-G-C-G-F#, setting the tone for how the song is going to be turned inside out. On the first and third beats, Elvin Jones hits two different cymbals; the second one has a majestic, vaguely eastern quality, foreshadowing the raga-like sound Coltrane’s soprano sax will produce. (He was studying Indian ragas at the time.) Then a piano vamp starts, and we are off. Coltrane plays the theme, then Tyner vamps again on different chords, then Coltrane plays the theme again, this time going to E major (“Girls in white dresses with blue satin sashes”), then back to the E minor beginning theme.

The E minor and E major themes together comprise the song’s “A” section. The song also contains a “B’ section, at the end of the form. This is when the lyrics turn glum: “When the dog bites/when the bee stings/when I’m feeling sad….” But Coltrane never gets to the B section until nearly the end, after 12 ½ minutes. And even then, as one of his biographers, Lewis Porter, states, “the B as written ends in G major, so that all the E major and minor before gets resolved. But Coltrane stays in E minor at the end, leaving it more brooding, thoughtful. It’s like one gigantic chorus.”

“In the meantime,” as Porter puts it, “he stretches out the sense of time.” He quotes Coltrane telling a French interviewer in 1962 that “this piece is built, during several measures, on two chords, but we have prolonged the two chords in order to set the scene and make it last. In fact, we have extended the two chords for the whole piece.” This decision is what enabled the quartet to so completely alter the feeling of the tune — to reimagine it entirely into the musical meditation it became.

Once Coltrane is back to the E minor, for 20 seconds or so, we hear lovely swirls of notes from his saxophone. Then, at about 2:18, Tyner’s solo starts. It takes up a bit less than one-third of the entire recording, but for me the piano solo has always been the reason this track is immortal.

Coltrane loved the song from the start. Porter, in his biography “John Coltrane: His Life and Music,” quotes him as telling a French interviewer, “Lots of people imagine wrongly that ‘My Favorite Things’ is one of my compositions; I would have loved to have written it, but it’s by Rodgers & Hammerstein.” Tyner, however, said he didn’t even like the song at first. How, then, to explain the beauty of his solo?

It’s impossible, really. As hackneyed as it may sound, it’s a journey. The playing isn’t technically overpowering or virtuosic, but shimmering, iridescent. The youngest member of the quartet, Tyner somehow was just 21 when it was recorded. But there is a lifetime of musical wisdom and authority in this solo. Most pianists could live to 100 and never record anything so lovely and evocative.

The solo toggles between E minor and E major. Again, there isn’t a lot of flashy or rapid playing. Perhaps that’s one reason it works so well – it contrasts with Coltrane’s antic, swirling sheets of notes. Lyricism set beautifully against tumult.

The chords are entrancing. You hear them over Jones’ loping waltz rhythm, which calls to mind the quiet but insistent sound of rain on a roof. Only for about 30 seconds, in the middle of the solo, does Tyner play something other than chords or octaves, when he tosses in a short figure.

This figure is the one time in the entire solo that Tyner makes a “mistake.” At 5:03, you can hear him accidentally hit two keys at once. I think of this little moment as proof that this track was in fact recorded by human beings, and not by musical gods. That one little “wrong” note, out of the thousands of notes in the piece, imparts a kind of wabi-sabi cast to the soundscape.

Just as the quartet deconstructed “My Favorite Things” on this recording, they would play it very differently live. Coltrane told the French interviewer that “My Favorite Things” was “my favorite piece of all those I have recorded. I don’t think I would like to do it over again in any way, whereas all the other discs I’ve made could have been improved in some details. This waltz is fantastic: when you play it slowly, it has an element of gospel that’s not at all displeasing; when you play it quickly, it possesses other undeniable qualities. It’s very interesting to discover a terrain that renews itself according to the impulse that you give it. That’s, moreover, the reason we don’t always play this song in the same tempo.”

Several recordings of live performances exist, and it is striking to hear how the renditions evolved. In 1963 at the Newport Jazz Festival, Roy Haynes is subbing for Elvin Jones on drums; the tempo is faster, the rhythm spikier. This time Tyner does play long lines of single notes. The song is over 17 minutes long. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=14EergYBa9o

At Newport in 1965, Jones is back on the drums, playing much more actively and dynamically than on the studio recording. Tyner again plays single-note lines. This version is a bit shorter than the 1963 one, but it’s still played faster, and is still longer than the studio take. The crowd chants for more at the end, but the announcer tells them that it’s almost midnight and time to go home, but please come back tomorrow for “Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck and others.” The quartet clearly knew the power of the song as a set-closer — indeed as the close to the entire day of music at the festival. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wxi4UCfvw7o

Less than a month later, they performed at a festival in Belgium. This performance was filmed for a documentary, and the performance of “My Favorite Things” can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ehYM_cg2DHI&t=886s If the musicians were at the top of their game when they first recorded in 1960, they were at the absolute zenith of their art now, in August 1965.

This performance is nearly 21 minutes long. It makes for riveting viewing. There are many closeups of each musician. Each man is intently absorbed in his own playing, yet somehow interacting with the others perfectly. Jones told the New Yorker’s jazz critic, Whitney Balliett, “Every night when we hit the bandstand — no matter if we’d come five hundred or a thousand miles — the weariness just dropped from us. It was one of the most beautiful things a man can experience. If there is anything like perfect harmony in human relationships, that band was as close as you can come.”

There are shots of Coltrane, eyes closed, literally seeming to fight his saxophone to coax more notes out of it. Jones, dripping with sweat, is blasting away with unrestrained power, but maintaining the beat with precision. Jimmy Garrison, who had grown up in the Philadelphia jazz scene with Tyner and had become the quartet’s regular bassist in 1962, anchors it all. The images of him, deep in concentration, and the extreme closeups of the strings on his bass, are strikingly beautiful. He is the calm at the eye of the storm.

As for Tyner, this solo is almost unrecognizably different from the studio recording. At the beginning, at 3:30, we hear those gorgeous chords. But barely 30 seconds later, he is weaving beautiful single-note lines over different chords. A minute and a half later, he is pounding away at the chords with both hands. Then more lines. Then starting at 7:20 he is literally banging the piano with his fists. A quiet interlude at 8:15 moves us back into E major.

The solo goes on for another four minutes. Then Coltrane comes back to the stage, after having retreated to the back during Tyner’s solo, and blows for seven more minutes. For long stretches his eyes are tightly closed. What is he thinking?

He’s not thinking at all. Coltrane was once quoted as saying that “overall, I think the main thing a musician would like to do is give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things that he knows of and senses in the universe…. That’s what I would like to do. I think that’s one of the greatest things you can do in life, and we all try to do it in some way. The musician’s is through his music.” Watching this footage, you can see him devotedly, intensely, doing just that.

Coltrane only had two years to live. He would die of liver cancer at 40 in 1967. He had become a very spiritual man — a process which started in 1957 when he finally quit heroin. That journey, and the continued musical evolution that went along with it, are fascinating subjects in their own right.

Some people worship John Coltrane — literally. He was canonized, 15 years after his death, as St. John Coltrane in the African Orthodox Church, and Sunday Mass is held every week at the St. John Coltrane Church in San Francisco. The church is a community institution, a performance space, an organizer of food drives and social engagement. It began when its founder heard Coltrane play at the Jazz Workshop, in the North Beach neighborhood. He told a New York Times writer, “It was as though he was speaking in tongues and there was a fire coming from heaven — a sound baptism. That began the evolutionary, transitional process of us becoming truly born-again believers in that anointed sound that leaped down from the tone of heaven out of the very mind of God, stepped from the very well of creation and took on a gob of flesh, and we beheld his beauty as one that was called John.”

Sometime back in the late 1980s or early 90s, I attended a Sunday service at the church when I was in San Francisco. It was a unique scene. People were chanting prayers along with a live band playing Coltrane’s music — mostly his later, explicitly religious works like “A Love Supreme.”

I don’t worship John Coltrane. But when I lie on the floor and listen to “My Favorite Things,” it might be what for me could be called a religious experience. Some people say that nature is their cathedral. For me, those 13 minutes and 46 seconds, that four men recorded 65 years ago this month, might be something like that. When I enter them — especially the four-minute, 45-second interior chapel of McCoy Tyner’s piano solo — I do feel something close to the sublime.