by Philip Graham

When William K Gillespie was a student in one of my fiction writing workshops at the University of Illinois in the late 1980s, he turned in a brilliant, 36-page (single spaced!) story. A story absolutely typical of his talent and ambition. In the following years William went on to study under and impress a stellar cast of mentors, among them David Foster Wallace, Robert Coover, Brian Evenson, and Carole Maso. He was granted one of the first MFAs in Electronic Writing (from Brown University), and he established his own cutting edge press, Spineless Books. Since then he has written in every imaginable form, and is now organizing his diverse and interwoven oeuvre into a vast digital warren on the Web. We spoke recently about this project’s past, present, and fu…

by Philip Graham

When William K Gillespie was a student in one of my fiction writing workshops at the University of Illinois in the late 1980s, he turned in a brilliant, 36-page (single spaced!) story. A story absolutely typical of his talent and ambition. In the following years William went on to study under and impress a stellar cast of mentors, among them David Foster Wallace, Robert Coover, Brian Evenson, and Carole Maso. He was granted one of the first MFAs in Electronic Writing (from Brown University), and he established his own cutting edge press, Spineless Books. Since then he has written in every imaginable form, and is now organizing his diverse and interwoven oeuvre into a vast digital warren on the Web. We spoke recently about this project’s past, present, and future.

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website, Collected Writings of William K Gillespie and Friends, lists and features the daunting range of genres in which you’ve written, and some of which you’ve probably invented: besides fiction, journalism, songwriting, sound collage and radio theater, there’s also “the longest literary palindrome ever written,” and “newspoetry,” to name just a small portion of your various literary explorations. Yet your career, seen in this perspective, rather than seeming scattered instead seems like solid evidence of a unified, voracious imagination.

Philip Graham: The home page of your new and expanded author’s website, Collected Writings of William K Gillespie and Friends, lists and features the daunting range of genres in which you’ve written, and some of which you’ve probably invented: besides fiction, journalism, songwriting, sound collage and radio theater, there’s also “the longest literary palindrome ever written,” and “newspoetry,” to name just a small portion of your various literary explorations. Yet your career, seen in this perspective, rather than seeming scattered instead seems like solid evidence of a unified, voracious imagination.

William K Gillespie: Thank you. I’m inspired by Harry Mathews, Julio Cortázar, and Italo Calvino, who produced books so singular that each seemed to be by a different author. Visual art, music, and literature have a lot to learn from one another, and transposing ideas from one to the other is great fun.

PG: This transposition of ideas from one art form to another is certainly a hallmark of your website, and yes, your spider-like orchestration of it all is impressive. Can you say more about its architecture?

WG: In addition to preserving old works from moldy word processor files and decrepit websites, the Webwork — my new site — has hidden tools to help me compose complicated fictions spread across multiple books, forms, and media. There’s only a hint of this functionality visible now: at the bottom of the site you see an incomplete list of characters in my work. Eventually this will allow the assiduous reader to track characters between works and learn secret backstories.

The Webwork project started when I was first wowed by good, millennial serial television, like The Wire. Earlier I grew up with crap TV whose episodes were meant to be endlessly shuffled in reruns and not viewed in sequence. I remain mad with curiosity about how a team of writers—probably total strangers to each other—can produce something so seamless, rich with story, with long plot arcs stretching across seasons, sometimes with closure, all edited down to the exact minute. I want to steal these techniques for print literature! But I’ve found not a shred of information online or in print about how these writing teams make decisions or keep track of them.

So I set out to build software that could help me write complex, multi-character, serial fiction on my own. Sans AI, btw.

The Webwork is bespoke to help inspire and organize my writings in accordance with my favorite perversions: an obsession with form, constraint, and media; fictional characters who write books I actually publish; careful use of metaphor as articulated by George Lakoff et alia; characters who exist beyond the boundaries of the stories in which they appear (something your latest novel does very well!); and the idea that different characters’ points-of-view (POV) on the same events might yield very different stories. I concede that storytelling has become an unnecessary tool in sophisticated literature, and the idea of closure seems to offend many; I just like it right now.

PG: “Fictional characters who write books I actually publish” sounds like Fernando Pessoa and his various poetry “heteronyms”—interior versions of himself to whom he gave names, and histories, and distinctive poetic aesthetics. But Pessoa mainly collected all these variations of himself in a large trunk, which was discovered after his death, keeping Portuguese literary editors busy for nearly a century ever since. You seem to be far more organized, an urban planner of your own inimitable city of seemingly limitless artistic forms.

PG: “Fictional characters who write books I actually publish” sounds like Fernando Pessoa and his various poetry “heteronyms”—interior versions of himself to whom he gave names, and histories, and distinctive poetic aesthetics. But Pessoa mainly collected all these variations of himself in a large trunk, which was discovered after his death, keeping Portuguese literary editors busy for nearly a century ever since. You seem to be far more organized, an urban planner of your own inimitable city of seemingly limitless artistic forms.

WP: Ah, Pessoa! I claim “plagiarism by anticipation,” as the Oulipo put it. If I had more success with publishers, I might not have developed the organizational methods I now rely on as my own archivist. My dear mom, the poet Junetta Gillespie, didn’t use many heteronyms, but left behind her own trunk of manuscripts. By its size alone, it’s evidence of tremendous dedication. But there are no scholars available to sort it out. I’m trying to avoid leaving a trunk to my own kid, because it wouldn’t be as good as Pessoa’s. He dies and his authors live on.

PG: Or you might say that Pessoa’s heteronyms have become his afterlife. Let’s talk about closure and endings a bit more? I’ve found, at my advanced age of 74, that “endings” are more like bookmarks in a larger, continuing story—at least in relation to looking back at my life, especially when it comes to other people (sometimes people I haven’t seen in years or even decades). Perhaps it’s a bit of added wisdom, or a reduction in stupidity (could that be the same thing?), but I’ve found, on reflection, complexity in people where I hadn’t previously suspected it. These quiet, private revelations have been a continuing influence on my latest novel, which I began writing in 1993. Though finished, and published, I now keep adding to the novel’s digital version, pulling various characters out of stasis and allowing them to expand.

WG: What the Dead Can Say is a remarkable achievement that keeps on achieving. I hope it never ends. And getting older is underrated! I don’t claim that there is any one way to write fiction, or that “closure” actually exists, even in death. And certainly not in The Wire. The Beatles, on the other hand, wrote great endings. Only a third of their songs use a fade-out; the rest end on a smart chord. Poetic forms like the traditional sonnet, ludic forms like the palindrome, Oulipian forms such as the “melting snowball” all come to hard endings in accordance with their form.

At Swarthmore and Stanford circa 1950, my mom’s generation learned to write poetry in the meter of Beowulf — can you imagine? — but for me to do so around the turn of the millennium would have gotten me thrown out of poetry school. So I taught myself to write rhyming verse in a basement in the summer: lots of strict, rhythmic nonsense that may never leave my hard drive. Now I’d like to learn to write stories that play with resolution. I’m naughty. To borrow from the Kinks, I have a “dedicated ignorance of fashion.”

At Swarthmore and Stanford circa 1950, my mom’s generation learned to write poetry in the meter of Beowulf — can you imagine? — but for me to do so around the turn of the millennium would have gotten me thrown out of poetry school. So I taught myself to write rhyming verse in a basement in the summer: lots of strict, rhythmic nonsense that may never leave my hard drive. Now I’d like to learn to write stories that play with resolution. I’m naughty. To borrow from the Kinks, I have a “dedicated ignorance of fashion.”

But of course even in a “closed” Webwork fiction, the characters and their children will appear in other stories, and there may be questions raised in one story that are answered in another story, or maybe a song. The Webwork uses the same list for authors as it does for characters, enabling diegetic levels to unfold into story universes within story universes.

PG: Heady stuff! But first, thank you for that observation of the endings of Beatles songs. Since reading your comment, I’ve been returning to their discography with new enjoyment of the last few seconds of their songs.

Anyway, characters who are authors who are characters: wonderful. I hope our conversation will encourage readers to circulate with confidence the nested universes of your website. Would you mind taking us on a brief tour of one of those branching correspondences?

WP: I’d love to. I’m especially interested in talking about character with you, Philip. Full disclosure to readers: I was your creative writing student circa 1988, and have remained your friend, fan, and mentee ever since. I never told you this: as a young fiction writer, I recoiled when you spoke about characters who had their own volition independent of their author’s plans for them, like ghosts. But doesn’t the writer compose everything? I thought. Since then, I have accrued decades of experience with disobedient characters. I know that, no matter what the architect thinks, they’ll do what they feel they need to do, or else they are no more real than marionettes. This is some magic I don’t understand, and I’m okay with that.

PG: I think the best description of this magic comes from James Baldwin, in his novel Another Country. In that novel, an aspiring writer, Vivaldo, can’t seem to induce his characters to, well, breathe. Baldwin writes: “They were waiting for him to find the key, press the nerve, tell the truth. Then, they seemed to be complaining, they would give him all he wished for and much more than he was now willing to imagine.”

PG: I think the best description of this magic comes from James Baldwin, in his novel Another Country. In that novel, an aspiring writer, Vivaldo, can’t seem to induce his characters to, well, breathe. Baldwin writes: “They were waiting for him to find the key, press the nerve, tell the truth. Then, they seemed to be complaining, they would give him all he wished for and much more than he was now willing to imagine.”

WG: Beautiful. In the Webwork, when I create a character, I’m asked to assign it a birthday and a death day. These are then entered as events in an overall timeline of the story universe. From the birthday, the Webwork will also pull the Chinese and western (Babylonian) zodiac signs, for additional inspiration. There are a few more tools to help define the characters. Whether or not the characters will put up with this remains to be seen.

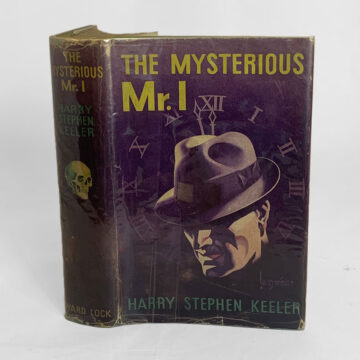

When this gets weird is when database structure starts to impose its own design on my fiction. For example, I have to answer the same questions for every character, so (in keeping with the techniques of Harry Stephen Keeler) I’m not really allowed to have what the kids call NPCs (Non-Player Characters). Any time a major character orders a pizza, the person who delivers it will already also be a major character. There are no mere “foils”, no empty sexual encounters, no working people blending into the background while our lead strolls around Manhattan name-checking intersections.

PG: Yep, you have always been a great admirer of Oulipian literary constraints that become windows into previously unsuspected possibilities. As for the interweaving of characters, you’ve created an extraordinary webwork map of the characters’ interactions in your novel Keyhole Factory (which I believe is one of the best, if not the best, pandemic novels ever written).

You’ve mentioned the influence of Harry Stephen Keeler, a writer I’m guessing not many readers are aware of. Could you say a bit more about him?

WP: Harry Stephen Keeler is worth a Google. Here’s an overview published in Ninth Letter. He was a twentieth-century Chicago detective novelist who developed a technique of writing proto-encyclopedic novels so bizarre he was dropped first by his English-language publishers, and, then, by his Spanish-language publishers, and ultimately all publishers. But he continued to crank out manuscripts until his death. His plot-construction handbook, The Mechanics and Kinematics of Web-Work Fiction, was barely ever in print, but I find it fresh and useful and full of great narrative visualizations that resemble electrical wiring diagrams. The nature of his work meant that characters and their relations were the backbone of his fiction. I like people—real, imagined, or in-between—so I like to see them placed at the center of fiction now and then. My Webwork owes its name to Keeler, who died long before the World Wide Web.

WP: Harry Stephen Keeler is worth a Google. Here’s an overview published in Ninth Letter. He was a twentieth-century Chicago detective novelist who developed a technique of writing proto-encyclopedic novels so bizarre he was dropped first by his English-language publishers, and, then, by his Spanish-language publishers, and ultimately all publishers. But he continued to crank out manuscripts until his death. His plot-construction handbook, The Mechanics and Kinematics of Web-Work Fiction, was barely ever in print, but I find it fresh and useful and full of great narrative visualizations that resemble electrical wiring diagrams. The nature of his work meant that characters and their relations were the backbone of his fiction. I like people—real, imagined, or in-between—so I like to see them placed at the center of fiction now and then. My Webwork owes its name to Keeler, who died long before the World Wide Web.

PG: Extraordinary, that Keeler so long ago was able to imagine some analogue form of what would later become the internet. And your Webwork map of your novel Keyhole Factory is quite a tribute to him.

Now that I’ve twice mentioned my admiration for your novel, let’s talk about it a bit more. It’s a book that is extremely—and successfully—playful with form, while much of its content depicts a pandemic swiftly ripping through the world. And yet it’s compulsively readable and is filled with engaging (though many soon to be dead) characters.

WP: Thanks so much! Keyhole Factory was published in 2012 by Soft Skull (pre-Covid 19), is still in print, and can be ordered through indy booksellers. As it happens, this interview is, for me, kind of a flare before I go underground for a decade and compose about ten more fictions in the Keyhole Factory universe, set before, during, and after the (fictional) pandemic. My Keeler map is going to look like a plate of multicolored spaghetti when I’m done. I’m guessing that you’re experiencing something similar: exercising normally underused literary muscles, what David Foster Wallace referred to (a bit derisively) as “left-handed push-ups”?

WP: Thanks so much! Keyhole Factory was published in 2012 by Soft Skull (pre-Covid 19), is still in print, and can be ordered through indy booksellers. As it happens, this interview is, for me, kind of a flare before I go underground for a decade and compose about ten more fictions in the Keyhole Factory universe, set before, during, and after the (fictional) pandemic. My Keeler map is going to look like a plate of multicolored spaghetti when I’m done. I’m guessing that you’re experiencing something similar: exercising normally underused literary muscles, what David Foster Wallace referred to (a bit derisively) as “left-handed push-ups”?

PG: Yeah, in the expanding digital version of my latest novel, What the Dead Can Say, I’m periodically adding to the afterlives of the book’s many ghostly characters, while at the same time adding several “bonus” chapters that continue the novel’s world hundreds of years into the future. So we’re both experiencing the exhilarating rush of having the creative freedom to attempt morphing a book into a larger project.

WG: One of the many good things about being a sub-mid-list novelist is total freedom. Keyhole Factory is a novel made of stories, in the shadow of Invisible Cities, A Certain Lucas, and Jesus’ Son. Each story tends to have a different character’s point-of-view, and is composed in a particular style or form. For example, there’s a story entirely in a footnote, a story as discrete blocks of text showing disparate POVs at the moment the power goes out worldwide, and a story as a musical score of simultaneous radio transmissions.

In the middle of* Keyhole Factory*, during the novel’s depiction of a pandemic crisis, the forms become fragmented. I imagined that a total global meltdown would also spell the meltdown of a dominant narrative explaining what was happening—some think the pandemic is God, some think it’s Earth’s revenge on humanity, some think it’s a utopian revolution, and some see a conspiracy of elites. I had an IT job on 9/11/01, and was at work, with a great internet connection, when the attacks began. I remember that anything seemed possible for a few bewildering hours, until Cheney et al assigned blame and swore military revenge against whoever they wanted to invade.

What is not known is that my novella Steal Stuff From Work was originally chapter 2 of Keyhole Factory, but trusted advisors told me it was too long and should be published separately. And while I’m telling secrets, the Webwork is the first time I acknowledge my various heteronyms. Araki Yasusada I ain’t. So if anybody starts to dig my writing the way I dig Calvino, Graham et al., there are a lot of (as the kids say) “easter eggs” to find. We must always seek to reward the assiduous reader!

Finally, in Keyhole Factory each story is also given a picture instead of a title, a technique I’ve not seen in books, but which is used in The Butthole Surfers’ Hairway to Steven LP.

PG: How cool, images instead of words. Kind of like Prince’s little iconic doodad standing in for his name. The undercutting of expectations reminds me of a novella by Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Chasing Homer. Each chapter of the book comes with a QR code that leads to an accompanying percussive musical score.

PG: How cool, images instead of words. Kind of like Prince’s little iconic doodad standing in for his name. The undercutting of expectations reminds me of a novella by Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Chasing Homer. Each chapter of the book comes with a QR code that leads to an accompanying percussive musical score.

WG: Ah, the glyph formerly known as “Prince”! To get away with a name that can’t be spelled, I think you have to be as fabulous as, well, Prince. But I’m glad we could work The Beatles, The Kinks, Prince, and the Butthole Surfers into our discussion of literature! As for Krasznahorkai, his books look great, but I haven’t read one yet. I was in Budapest in 2022, asking every tour guide to recommend Hungarian literature, and asking every record store owner to recommend Hungarian rock. Somehow, Krasznahorkai never came up. Instead I picked up Antal Szerb’s Journey by Moonlight. My tour guide said her “hipster boyfriends” liked that one. I did not feel complimented, but I bought the book.

Back in the day, you handed out a list of recommended books no other English teacher would recommend. (Well, most of them weren’t originally written in English, but were more than worthy of the attention we gave The Great Gatsby.) If I have good taste, it’s thanks to office hours with you. You’ve had a lot of students since then, presumably have kept adding to the list, kept distributing it out to students who care, and America is a better reader and writer thanks to you!

PG: Ah, that reading list. I’ve been adding to it over the years. It now clocks in at 25 pages, and Keyhole Factory is included on that list. I’ll be happy to send you the latest version. Meanwhile, I’m so looking forward to reading, as the years pass, the developing construction site of the burgeoning neighborhood of your already marvelous Keyhole Factory.

WG: Thank you, my friend. Before we part, there’s a drunken elephant in the room, so I have a PSA for younger writers:

This Thanksgiving, when you admit you’re a writer, and conservative Aunt Gladys pinches your cheek and says, “Someday you’ll be as rich and famous as Stephen King,” tell her you’re not out to get rich and famous, you’re out to express your humanity and protect her first amendment rights. Tell her that, when the human race is ambivalent about extinction, and we have an attempted fascist takeover in the US, our collective literary agenda, as dictated by the New York book-publishing offices of dubious corporations, even by academics, even by Stephen King, is frivolous. Suggest to Aunt Gladys that, as to whether literature has power against the oppressor, we may not know as long as we capitulate our lit to a system controlled by the oppressor. Point is, to be a novelist or poet now is to choose between sacrificing power for a dubious legitimacy, or wielding power through an independent voice, not dependent on royalties, tenure committees, blurbs, publishers, or any success other than that you define. Don’t compete against those who would be friends. Don’t be the frog who boils to death in the metaphor about the frog who boils to death, Aunt Gladys, DIY or die!

I’m sure she’ll understand, and the ensuing holiday will be a lively one, the best Thanksgiving ever.

***

The website Collected Works of William K Gillespie and Friends is very much worth exploring. To encourage the gentle reader, I’m including here short excerpts from and links to four books in the growing and ever-curiouser literary universe by Gillespie and some of his various pseudonyms.

“Life of an Electron,” an excerpt from *Letter to Lamont *by William Gillespie, in which an electron offers its perspective on the history of the universe:

Everyone talks about the Bang as if it were a great party that got a little out of control. I remember the time before. What I remember is that I was not me, I was all matter and so was everybody else and the burning unity, the singularly hot and dense intimacy, was a far better universe to me than the slow astronomical ballet we are playing out now, stretched for millennia as imperceptibly thinning dust. You are about to give me advice: maybe I should join a star. I assure you, it is not the same. Being a star seems nice and warm, really bright and industrious, until you grow cold and collapse . . .

*

Excerpt from Mars Need Lunch by “Jimmy Crater and June Crater-Crash,” in which we visit “the Siberian sparseness of the Midwest”:

It’s a hoax, all these fields of food. Still, it gives one comfort. New Yorkers take one look at the horizon and get dizzy, start to panic. It’s partially the oxygen that saturates our air—pure, exhaled by leaves—that makes them lightheaded, but they associate the feeling with horigo: a fear of horizontal distances. They are afraid of the risk of starving to death in a provincial city where you need a phone book to find a taxicab and there are no restaurants open after three AM . . .

* Excerpt from the novel Steal Stuff from Work, by “Jasper Pierce,” in which the despairing narrator begins to collect jobs, and “things stolen from jobs”:

I’ve had jobs every day of my life since I was eight. My spirit had just about been hammered flat. Working took its toll on me, until the day I started taking my toll on it. I had become so exhausted and demoralized that by the end of the day I was no longer taking any of myself home from work. So I started taking some of my work home with me . . .

*

An excerpt from Keyhole Factory, by William Gillespie, in which a world map, dotted with fifteen startling vignettes, each only one short sentence long, illustrates how the pandemic swiftly spreads across the globe. Map to be found here.

***

William K Gillespie has published 14 5/6 books of poetry and prose under six different names. He has worked as a paperboy, dishwasher, waiter, librarian, phone book delivery person, temp, teacher of creative and uncreative writing, webmaster, technical writer, valet, science writer, editor, proofreader, agriculture laborer at a free utopian hospital, “marcom content provider”, radio show host, assistant at Dalkey Archive Press, and is Treasurer Emeritus of Burning Deck. He is also founder or co-founder of University of Illinois Creative Writing Club, The Weird Leading the Bored (theater group), The Eclectic Seizure Radio Theatre Collective (community radio show), Spineless Books (publishing house), Spybeam Books (online bookstore), Newspoetry (Associated Poets), The Unknown (writing band), gleed (punk band), Soda Gun (rock band), and Sputz (beer commercial cover band). He divides his time between Champaign and Urbana; Minneapolis and St. Paul; and the Wisconsin coast. He has raised nine cats, one dog, and is currently raising a great kid, who drums with him in a Fountains of Wayne cover band (Bones and Firefly).

Philip Graham, a Professor Emeritus of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, is the author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, including the novels How to Read an Unwritten Language and (as Author Unseen) What the Dead Can Say, and the story collections The Art of the Knock and Interior Design. He has also written a collection of travel essays, The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches from Lisbon and is the co-author, with his wife, anthropologist Alma Gottlieb, of two memoirs of Africa, Parallel Worlds and Braided Worlds. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Washington Post Magazine, North American Review, Paris Review, Missouri Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and elsewhere. A co-founder and fiction/nonfiction editor of the literary/arts journal Ninth Letter, he is currently the Editor-at-Large for the journal’s website.