by Mark R. DeLong

Still from Cars (2006)

Still from Cars (2006)

1.

Regular snowmobile trails bored us kids in the closing years of the 1960s. They wound through the woods, dipping here and there just enough to stall my uncle’s boxy old Evinrude machine with its odd orange and too smooth track. My cousins and I wanted slop…

by Mark R. DeLong

Still from Cars (2006)

Still from Cars (2006)

1.

Regular snowmobile trails bored us kids in the closing years of the 1960s. They wound through the woods, dipping here and there just enough to stall my uncle’s boxy old Evinrude machine with its odd orange and too smooth track. My cousins and I wanted slopes—frozen white waves—to test our snow jets as if we had exchanged whining two-cycle engines for surfboards and were scaling waves on Hawaii’s North Shore. The slopes we chose in winter were man-made and, now that I look at them, rather tame. Before winter idled roadbuilding, earthmovers had cut paths for a new “Interstate” outside of town, pushing the hills into the valleys and leaving steeper cut-off grades to bound highway lanes; the earthmovers leveled the roadway through the landscape. For a winter in the 1960s, the highway’s deer fence still lacked, so we could sneak through and leap our snowmobiles over the edge of the snowy wave. We carved track parabolas up to its crest.

That was the story of I-35 near Moose Lake, Minnesota, where I was a child—at least before the wide interstate pavement opened to cars. I’m certain Moose Lake’s town council didn’t have as much fun with the interstate as I did with my cousins that winter. They knew what would happen to town traffic and businesses once the highway opened. It would dwindle and the town with it. The same story played out wherever a “superhighway” cut through the landscape.

They tried to avoid having their town turn into another small place where a gas station or two near the highway ramps would become the only retail businesses, and they had a plan. One could say they hijacked highway traffic to run through the town’s center on two-lane US Highway 61. You couldn’t exit and re-enter the new highway at the same interchange; whoever would get off I-35 would have to run through town to re-enter the interstate on an on-ramp at the opposite end.

It was a cunning plan. It didn’t work.

Roads shrink spaces, “superhighways” especially, and the problem Moose Lake’s town fathers faced was more than traffic that bled from Highway 61—the Main Street running through Moose Lake—onto the four lanes of I-35 that scooted a couple miles to the east. The road increased mobility, and efficiency of travel increased space that area residents could easily access for shopping and entertainment. They could go the “The Mall” in Duluth in less than an hour or push a shopping cart through the grocery aisles at Target rather than in the much smaller local Red Owl Food Store. The placement of on- and off-ramps for I-35 was irrelevant to such matters.

Moose Lake, as a place, became a smaller dot on the map after Interstate 35 skirted the village. Eventually, the town fathers abandoned their nefarious plan to hijack traffic, and on- and off-ramps were added to the north and south exchanges of I-35. Though the highway attracted development closer to the ramps, after suffering blows to the local economy and, perhaps, I-35’s bypassing of the town, Moose Lake’s population flagged. It has since recovered—indeed, has grown from pre-interstate days.

2.

As snow receded in 1916, Walter S. Thompson rolled his motorcycle up Colorado Highway 14 that, at the time, wound a single lane of gravel along the Poudre Canyon (locals pronounce Poudre “Pooder”). The canyon was left by glaciers in the Ice Age and since then has been carved some more by the Cache la Poudre River. Thompson got off his motorcycle at a curve huddled against three steep inclines. “We came upon a most beautiful spot, which seemed to hypnotize me,” he later wrote in his memoir, “and I found myself with a longing to stay there.” Thus charmed by the site, Thompson claimed it as his homestead, built a resort—a dance hall really—and christened it “Mishawaka” after the town in Indiana where he grew up. The geography of the Mishawakas could hardly be compared: Indiana is flat where the town sits about 800 feet above sea level; Thompson’s Mishawaka is nestled high in the Front Range of the Rockies, 17 miles up Highway 14 from Bellvue, the nearest post office.

An undated photo of the early Mishawaka buildings at the base of the Poudre Canyon and nestled alongside the Cache la Poudre River. Still from Long Live The Mish (YouTube).

An undated photo of the early Mishawaka buildings at the base of the Poudre Canyon and nestled alongside the Cache la Poudre River. Still from Long Live The Mish (YouTube).

Thompson chose the place for music, and over a century later, we drove up Highway 14—its two lanes paved long ago—to “The Mish” for a performance by Sunsquabi, a band based in Denver. As we drove the forty-some miles from Fort Collins in the dark, I was struck by the easy “naturalness” of the trip that not that long ago would have been long and arduous at best. But that night, it was a diversion, a recreation, a practically effortless gathering of people loosened by beers, wine, and weed all listening to a few hours of music and “dancing” together in a listing and leaning kind of way. Many, maybe most, of the attendees arrived by shuttle bus from Fort Collins. Walter S. Thompson’s old dance hall never echoed music on the canyon walls like the music Sunsquabi performed that night, but The Mish continues to flourish with variety—besides Sunsquabi even the Colorado Symphony Orchestra performed there in 2013.

The road brought a new musical culture to a canyon with its river that, Thompson said, “rippled like sweet music as it worked its way over the rocks.” Before he heard the song of the river, members of the Ute tribe had heard it where they hunted and lived. In a sense, the transformations of road turned the Poudre Canyon mountain goats into annoyed audiences of human noises echoing from The Mish.

The road has, in no small way, claimed the land and placed it into human hands that reshape it and occupy it.

Ben Bradley, a history professor at the University of Guelph, has studied the interplay of mobility and the environment and has focused particularly on the Canadian National Park system, mainly through the lens of western Canada’s provincial and national political maneuvering, economic history, and shades of difference among bureaucratic personalities. Bradley has laid out some of the “distinct regional histories of automobility and distinct regional relations between driving, the environment, and landscape experience,” as he put it in one of his articles.1Ben Bradley, “‘Behind the Scenery: Manning Park and the Aesthetics of Automobile Accessibility in 1950s British Columbia,’” BC Studies, no. 170 (2011): 41–65. Bradley has particularly focused on western Canada and the interplay of automobility and Canada’s National Park system. He has documented the ways that drivers’ aesthetic sense of nature—impressive as it is in the Canadian Rockies—has been shaped by bureaucratic choices of where roads traverse the landscape, what settlements and businesses can be seen from roadways and train tracks, or when stands of virgin forest should (or maybe should not) hug roadsides. Choices that the BC Parks Division made in the 1950s set a standard expected by tourists.

Bradley concludes his article on the E. C Manning Park by noting its embedded “aesthetics of automobile accessibility” that BC Parks continues to uphold:

With the passage of time, and the passage of countless motorists along the highway corridor through the park, the motoring public’s shared experience of Manning’s landscapes acquired more and more cultural and political significance, compelling the agency responsible for British Columbia’s provincial parks to continue meeting, to the best of its abilities, the very expectations it did so much to create.2Ben Bradley, “‘A Questionable Basis for Establishing a Major Park’: Politics, Roads, and the Failure of a National Park in British Columbia’s Big Bend Country,” in A Century of Parks Canada, 1911-2011, ed. Claire E. Campbell, Canadian History and Environment (University of Calgary Press, 2011), p. 102; https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/90066.

By focusing on the “aesthetics” of the car-accessible national park, automobility—which Bradley succinctly defines as “the constellation of spaces, objects, practices, discourses, and habits that surround the ubiquitous vehicle and the paths along which it travels”—has in many ways defined the national park not only in Canada but throughout North America. The aesthetics are sticky, too.3Ben Bradley, Jay Young, and Colin M. Coates observe this sticky quality of “fixed infrastructure” like roadways and railroads in their introduction to Moving Natures: Mobility and the Environment in Canadian History (2016): “These lines and networks transform the environment by their construction, and they also impose path dependencies. Over time, they become taken-for-granted aspects of everyday life, shaping people’s interactions with and perceptions of the environment for decades, even centuries” (p. 11).

We drivers on roads have steered our metal vessels without feeling the deep influence of the asphalt below us: The way it guides us, steers us. The way its dark fingers have crumpled space and demarcated destinations; the way the road itself has curated nature for us, in effect shaping our minds to behold the natural world as “natural,” even though contrived.

3.

But maybe roads themselves can also be “nearly natural,” at least by responding to natural landscapes?

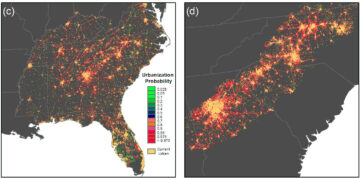

In 2060, as we orbit the earth on our vacations, the Southeast United States may look something like this at night: Large blobs of light emanating from concentrated urban areas with tendrils of light, often themselves blobby with illumination spider-webbing in a crescent from central Georgia (Atlanta, of course, the biggest blob) northeast to Charlotte, the North Carolina Triad, and the Research Triangle, both parts of the Piedmont Urban Crescent. The megalopolis has been called “Charlanta” and the greater region, the Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion.

Image (c) renders the researchers’ model predictions of population and development in the Southeast US; image (d) details the model’s prediction for “Charlanta,” which runs from central Georgia to north central North Carolina. From Adam J. Terando et al., “The Southern Megalopolis: Using the Past to Predict the Future of Urban Sprawl in the Southeast U.S”

Image (c) renders the researchers’ model predictions of population and development in the Southeast US; image (d) details the model’s prediction for “Charlanta,” which runs from central Georgia to north central North Carolina. From Adam J. Terando et al., “The Southern Megalopolis: Using the Past to Predict the Future of Urban Sprawl in the Southeast U.S”

But consider this contrast from the past: About ten miles south of my home in the Piedmont of North Carolina, a roadside marker notes a remnant of the “Indian Trading Path” (also known as the Occaneechi Path) that stretched southwest from the area around Petersburg, Virginia, into Georgia. Johann Lederer is credited with opening (or at least making white settlers aware of) the Indian Trading Path in an account published in 1670, though the path had been used for some time before—for hundreds or perhaps even thousands of years. Indeed, the path may have formed not only from plodding humans and their pack animals but also from migrating wild animals. Not a planned construction project, like a modern highway, the path grew from shorter pathways, “braiding” (as one historian put it) into an aboriginal byway.

Two-footed and four-footed creatures sought easy ways to traverse the land and cross rivers and streams, whether to trade goods or find safety, shelter, and food. Travelers respected, because they often had no choice, the affordances4(Pardon this note indulgence.) While I was writing this piece for 3 Quarks Daily, I ran across a blog post by Alan Jacobs, who drew attention to the use of the word “affordances” in Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Jacobs commented on the “affordances” that push technology; but, for the hobbits, “affordances” pushed them back to a trail they would rather not have taken. Jacobs: “I’m reminded of that passage in The Fellowship of the Ring where the hobbits are trying to get through the Old Forest, and the one way that they don’t want to go is down into the valley of the Withywindle. But they keep being forced down there. The lay of the land, the affordances of the land push them towards the place they’re trying to avoid. And eventually they discover that resisting those affordances is just too exhausting. And that’s what it’s like when we use social media, and when we use chatbots: it’s characteristic of all of our currently dominant technologies to force us to become devices. The entire system is oriented towards the transformation of what had formerly been human beings into devices. Jaron Lanier says You Are Not a Gadget but, increasingly, you really are. Eventually you’re drawn head-first into the roots of Old Man Willow and in danger of being crushed to death.

This explains why, in the face of varied but always vociferous complaints, the big tech companies keep shoving their AI programs in our faces, keep building out data centers in the face of protests, keep stealing people’s electricity and water, etc. etc. People say, You can’t force this on us against our will, and the techlords reply, Of course we can, we always have. Eventually down into the valley of the Withywindle we’ll go—unless we don’t enter the Old Forest in the first place.”

of the land. After all, river fords have certain characteristics that ease crossing, horses and oxen struggled with steep grades (12% grades were apparently judged to be the maximum safe incline), and resting places punctuated the trail every thirty miles or so, the distance of a good day’s walk. Many of those stops took root where fords eased crossing water; sometimes the places grew into towns.

One could say that the Indian Trading Path was as much a “naturally occuring” feature of the environment as it was a visible feature of human culture.

Nearly 400 years separate Johann Lederer’s notice on the Indian Trading Path and modern scholars’ projections of the megapolis called Charlanta. And yet, the ancient humble path and future’s meandering urban behemoth share a durable sinew, today manifest in the concrete ribbon of Interstate 85. I-85 is just the most recent highway project to have followed the pathway of trading Native Americans and their predecessors, sometimes even running atop the old path. Frederick Jackson Turner took note of the continuities of path and roadway in 1894: “[C]ivilization in America has followed the arteries made by geology, pouring an ever richer tide through them, until at last the slender paths of aboriginal intercourse have been broadened and interwoven into the complex mazes of modern commercial lines,” he wrote. He compared the expanding network of roadways and path to “the steady growth of a complex nervous system for the originally simple, inert continent.”5Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, Bobbs-Merrill Reprint Series in History, H-214 ([Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill], 1893), p. 210; http://archive.org/details/significanceoffr00turnuoft

Well, perhaps the continent was not actually “inert” but a living thing with seeds of byways and paths already planted in geography. Turner’s use of the “nervous system” is a useful metaphor and also a living, natural one.

What is this heritage of pathways that, stretching from foggy origins, layers haphazard footpaths, dug and bridged walkways, road construction and reconstruction—all respecting the natural affordances of geography? If it is a natural “propensity” of humans, as Adam Smith claimed, “to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another” and pathways are the natural support for that activity, then … are ancient and modern roadways also nearly natural phenomena?

4.

On October 8, Texas Governor Greg Abbott issued an order, saying, “Today, I directed the Texas Department of Transportation to ensure Texas counties and cities remove any and all political ideologies from our streets.” In Houston, protestors were arrested for obstructing an intersection when city workers began to remove a rainbow crosswalk in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. Blavity reported that “Montrose’s rainbow crosswalks doubled as the area’s landmarks and as a reflection of its deep-rooted LGBTQ+ history. They were first painted in 2017 and refreshed by the city on October 1 before being ordered off the street. The METRO team moved in just after midnight on October 20 to start the removal under the state’s deadline.”

The community responded with rainbow chalk art on sidewalks and side streets.

For the bibliographically curious: John Urry, “The System of Automobility,” Theory, Culture & Society 21, nos. 4–5 (2004): 25–39, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046059. Tom Lewis, Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming American Life, Updated edition (Cornell University Press, 2013). Mary Willson, “The Rescue of the Mishawaka,” Denver Westword, September 10, 2014, https://www.westword.com/music/the-rescue-of-the-mishawaka-5710304/. A brief video on The Mish: Long Live The Mish, produced by Stacey Grant and Eric LaCasse, directed by Andrew Schwartz (Koi-Fly Creative Productions, 2017), 10:09, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YD-Jb_vAv94. Ben Bradley, “Behind the Scenery: Manning Park and the Aesthetics of Automobile Accessibility in 1950s British Columbia,” BC Studies, no. 170 (2011): 41–65; and “‘Lucerne No Longer Has an Excuse to Exist’: Mobility, Landscape, and Memory in the Yellowhead Pass,” BC Studies, no. 189 (2016): 37–53. For a nationally scoped view of mobility and the environment, see Bradley et al., eds., Moving Natures: Mobility and the Environment in Canadian History, Canadian History and Environment Series, ed. Alan MacEachern, vol. 5 (University of Calgary Press, 2016), https://press.ucalgary.ca/books/9781552388594/. Rebecca Taft Fecher, “The Trading Path and North Carolina,” Journal of Backcountry Studies, 2008, https://libjournal.uncg.edu/index.php/jbc/article/viewFile/26/15. Fecher suggests studies that might be interesting and revealing: “[I]n the back country, there were blended communities. People of different ethnicity, class, and race were living together cohesively and productively by the late 1700s. This is an interesting fact that should be explored in greater depth due to its placement in an area later torn by racial divisions.” Adam J. Terando et al., “The Southern Megalopolis: Using the Past to Predict the Future of Urban Sprawl in the Southeast U.S,” PLOS ONE 9, no. 7 (2014): e102261, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102261. A good article on Charlanta.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Footnotes

- 1

Ben Bradley, “‘Behind the Scenery: Manning Park and the Aesthetics of Automobile Accessibility in 1950s British Columbia,’” BC Studies, no. 170 (2011): 41–65. Bradley has particularly focused on western Canada and the interplay of automobility and Canada’s National Park system.

- 2

Ben Bradley, “‘A Questionable Basis for Establishing a Major Park’: Politics, Roads, and the Failure of a National Park in British Columbia’s Big Bend Country,” in A Century of Parks Canada, 1911-2011, ed. Claire E. Campbell, Canadian History and Environment (University of Calgary Press, 2011), p. 102; https://directory.doabooks.org/handle/20.500.12854/90066.

- 3

Ben Bradley, Jay Young, and Colin M. Coates observe this sticky quality of “fixed infrastructure” like roadways and railroads in their introduction to Moving Natures: Mobility and the Environment in Canadian History (2016): “These lines and networks transform the environment by their construction, and they also impose path dependencies. Over time, they become taken-for-granted aspects of everyday life, shaping people’s interactions with and perceptions of the environment for decades, even centuries” (p. 11).

- 4

(Pardon this note indulgence.) While I was writing this piece for 3 Quarks Daily, I ran across a blog post by Alan Jacobs, who drew attention to the use of the word “affordances” in Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Jacobs commented on the “affordances” that push technology; but, for the hobbits, “affordances” pushed them back to a trail they would rather not have taken. Jacobs: “I’m reminded of that passage in The Fellowship of the Ring where the hobbits are trying to get through the Old Forest, and the one way that they don’t want to go is down into the valley of the Withywindle. But they keep being forced down there. The lay of the land, the affordances of the land push them towards the place they’re trying to avoid. And eventually they discover that resisting those affordances is just too exhausting. And that’s what it’s like when we use social media, and when we use chatbots: it’s characteristic of all of our currently dominant technologies to force us to become devices. The entire system is oriented towards the transformation of what had formerly been human beings into devices. Jaron Lanier says You Are Not a Gadget but, increasingly, you really are. Eventually you’re drawn head-first into the roots of Old Man Willow and in danger of being crushed to death.

This explains why, in the face of varied but always vociferous complaints, the big tech companies keep shoving their AI programs in our faces, keep building out data centers in the face of protests, keep stealing people’s electricity and water, etc. etc. People say, You can’t force this on us against our will, and the techlords reply, Of course we can, we always have. Eventually down into the valley of the Withywindle we’ll go—unless we don’t enter the Old Forest in the first place.”

- 5

Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, Bobbs-Merrill Reprint Series in History, H-214 ([Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill], 1893), p. 210; http://archive.org/details/significanceoffr00turnuoft