by Marie Snyder

There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and craving dopamine, appear to be more like a story we’ve constructed to understand our actions than a scientific explanation, and I’m not convinced it’s the best narrative to help us change our behaviours, particularly around tech-based habits.

There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and craving dopamine, appear to be more like a story we’ve constructed to understand our actions than a scientific explanation, and I’m not convinced it’s the best narrative to help us change our behaviours, particularly around tech-based habits.

As a hormone, it’s released by the adrenal glands (above the kidneys) into the bloodstream for slower, more general communications where it primarily helps to regulate our immune system. …

by Marie Snyder

There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and craving dopamine, appear to be more like a story we’ve constructed to understand our actions than a scientific explanation, and I’m not convinced it’s the best narrative to help us change our behaviours, particularly around tech-based habits.

There are contradicting views and explanations of what dopamine is and does and how much we can intentionally affect it. However, the commonly heard notions of scrolling for dopamine hits, detoxing from dopamine, dopamine drains, and craving dopamine, appear to be more like a story we’ve constructed to understand our actions than a scientific explanation, and I’m not convinced it’s the best narrative to help us change our behaviours, particularly around tech-based habits.

As a hormone, it’s released by the adrenal glands (above the kidneys) into the bloodstream for slower, more general communications where it primarily helps to regulate our immune system. As a neurotransmitter, it provides fast, local comms between neurons in the brain where it does a lot of different things including affecting movement, memory, motivation, mood, and mornings (waking up). It makes up 80% of the “catecholamine content” in our brain, the ingredients that prepare us for action. Our levels fluctuate throughout each day, so you don’t have to try to cram all your work into the early hours of the morning.

It’s largely discussed as the heart of our quest for pleasure, yet for decades studies have concluded that dopamine doesn’t affect pleasure, since we get a dopamine release before a rewarding activity, not after we’ve completed it. Instead, it affects how the brain decides if an action is worth the effort. A 2020 study found that increasing it with meds like Ritalin can motivate people to perform harder physical tasks. People with higher levels of dopamine are more likely to choose a harder task with a higher reward than an easier, low-reward task. Low dopamine doesn’t reduce focus, but it’s believed it provokes giving more weight to the perceived cost of an activity instead of the potential reward. Lower levels lead us to save energy.

So *why *do we think we crave it or, paradoxically, need to try to intentionally deplete it?

ACCIDENTAL MYTH-MAKING

Dopamine’s function wasn’t known until the 1950s, when Arvid Carlsson completely blocked the neurotransmitter in rabbits, which paralyzed them, clarifying dopamine’s necessity in self-initiated movement. The rabbits fully recovered with a shot of Levodopa (L-Dopa), which was later used (and still is) as a dopamine replacement agent to reduce the physical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. About the same time, Olds & Milner found that animals repeat acts that were followed by electrical stimulation of the brain, which prompted thinking of brain centers that focus on rewards. Roy Wise wrote about it in a 1978 paper.

Then in 1980, Wise wrote a paper that starts by acknowledging that discussing a “pleasure center” of the brain is inaccurate, but can be a useful paradigm for experimenting. At the time he thought the dopamine system was activated from food, sex, drugs, and social interactions. A 1997 study found it’s not getting a reward, but the anticipation of a reward that sends neurotransmitters racing, to help us predict and correct for errors in prediction. Dopamine helps us to learn about our environment. “The key element that causes dopamine neurons to fire is surprise, regardless of whether the outcome is rewarding or disappointing.” This was the thinking in the 80s, confirmed in the 90s, yet that attachment to the “pleasure center” was hard to shake.

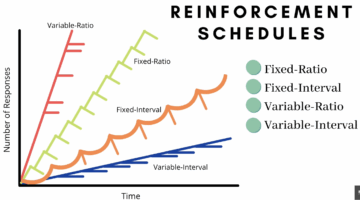

In 2011, Robert Sapolsky‘s work with monkeys pressing levers demonstrated that dopamine increased with anticipation and decreased at the end of the behaviour. More relevant to internet habits, when treats only were expected after a random number of bar presses (a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement – more on that later), twice as much dopamine was released, and monkeys pushed the bar more. Unpredictable rewards increase motivation. So if only* occasional *YouTube videos are entertaining to us, we’ll maintain clicking behaviours for far longer.

In 2012, further to the 1997 study, John Salamone and Mercè Correa published a comprehensive paper in Neuron on the myth of dopamine. Salamone spent most of his career arguing that dopamine is related to motivation, not pleasure. Soldiers with PTSD “show activity in dopamine-rich parts of the brain when hearing recorded gunshots,” which is hardly pleasurable. Stories that depression is from low dopamine or that addiction is from a hijacked reward system are not supported by closer examination. We gravitate to simple stories, but this one is far more complex with Salamone’s explanation going back to Schopenhauer (1837)! Dopamine “probably performs several functions, and any particular behavioral or neuroscience method may be well suited for characterizing some of these functions, but poorly suited for others. In view of this, it can be challenging to assemble a coherent view.” For instance, in some cases it impairs eating, and in others it doesn’t. Once again, depletion can “cause animals to reallocate their instrumental response selection based upon the response requirement of the task and select lower cost alternatives.”

The myth of dopamine being part of a pleasure center started growing legs in 2019 when Dr. Cameron Sepah used the term “dopamine fast,” despite that he explained at the time that it just makes for a catchy title, but it’s not to be taken literally since it has little to do with either fasting or dopamine. He proposed we stop ourselves from automatically responding to unhealthy stimuli around us, like notifications, and instead let ourselves feel lonely or bored from time to time, similar to G. Alan Marlatt‘s notion of urge surfing from 1985. Just wait for the urge to pass. Sepah also suggested timeblocking abstinence: put away devices for 1-4 hours each weekday evening, a full day each week; one weekend each month. and a full week each year. Great ideas, but an unfortunately catchy title.

The following year, Peter Grinspoon, MD, tried to bring the “maladaptive fad” to light, stating what we might think is obvious: “You can’t ‘fast’ from a naturally occurring brain chemical. … It doesn’t actually decrease when you avoid overstimulating activities.” Dopamine isn’t like heroin, which we can build a tolerance to. Don’t try to avoid dopamine, but do actively avoid stimuli that lead to unwanted behaviours. Grinspoon was especially concerned with extreme versions of dopamine fasting: people who stopped anything pleasurable, none of which affects dopamine levels at all but can cause other problems. What was actually being suggested was just a day of rest for mental rejuvenation and real life connections, like many religions have counselled:

“The modern wellness industry has become so lucrative that people are creating snappy titles for age-old concepts.”

WELL-MEASURED PLEASURE INDICATES THE GOOD

You’d think that might have settled things, BUT THEN Anna Lembke’s Dopamine Nation came out in 2021, which furthered the heroin myth that indulging in pleasures desensitizes us from dopamine. She was criticized for being simplistic andjudgmental, using anecdotes over hard data, overemphasizing personal blame, downplaying systemic factors, and conflating neurotransmitters with opium: “overusing your ‘pleasure center’ can result in not being able to find anything pleasurable at all anymore” is all sorts of wrong. The book sold well anyway. A 2023 op ed tried to dismantle the myth of dopamine hits, and another in 2024 called the book “promoting puritanism as an addiction cure.” An excellent read by Jesse Meadows asks, “What morals are being communicated to us through this particular science story?” and digs into Lembke’s previous work further as well as clarifying that heroin can cause a high without changing dopamine levels and that studies showing increases in dopamine associated with video games are “small and poorly replicated.”

“The dopamine mythos ultimately tells us that all the world’s problems are just inside our own heads, and the solutions can only be found in individual self-management.”

I wonder if that’s the part people resonated with that increased book sales. We feel out of control, and want a quick answer, and there’s a kernel of truth that we’re choosing pleasures poorly. We get that some pleasures are better than others. We get mad at ourselves for scrolling for hours, when we look up and realized we missed a gorgeous day outside, so there is a desire for some self-management that Lembke taps into. She appears to take an all or nothing approach, though, as if we’ll be ruined by enjoying great food and sex. Plato and Aristotle wrote about this, not in a moralizing way, but arguing that surely we want the most and best pleasures in our lives. For Plato, it’s all about measuring short term gains against long term losses. Don’t get so hammered that you’re sick all the next day because that’s a negative net sum of pleasure. Being mastered by pleasure is a form of ignorance, not sin. Aristotle agrees the solution is education: “we ought to have been brought up in a particular way from our very youth, as Plato says, so as both to delight in and to be pained by the things that we ought.” A few thousand years later, Nietzsche said, significantly more judgmentally, “All lack of intellectuality, all vulgarity, arises out of the inability to resist a stimulus.”

We don’t need to shame people for their vices in order to help them recognize how to get *more *pleasure, greater in number and duration, by being intentional about choosing less fleeting pleasures. We can teach kids the benefits of restraint, tolerating boredom, and using their imagination more to enable it to be used more. Now we understand brain plasticity, so we know that intentionally focusing for longer eventually makes it easier to focus for longer. We recognize hard work leads to more pleasure, and easy pleasures lose their luster. The big problem is that we know all the things, but we’ve become accustomed to low-hanging fruit. Even as an adult raised as an outdoorsy kid, the algorithms often own me. This evolutionary mechanism of motivation that provokes long durations of effort worked for millennia to keep us hunting and foraging, particularly when food is scarce, but more and more, changes in production and distribution and then technology have led to a very different system in place that we haven’t yet evolved for. We’re like squirrels living on a peanut farm unable to stop collecting nuts despite part of us clearly knowing that nobody needs this much continuous information or entertainment. To live with it, the skill of measuring well needs to be taught and re-taught regularly.

Reducing exposure to the object of our compulsions is a great idea. There’s nothing wrong with that part of the trend. Despite not being remotely religious, I regularly observe Lent at the end of winter because it feels easier to do knowing about a billion other people are also depriving themselves of something during those 40 days. For me, it’s a yearly re-set towards a more simple life, a reminder of what I don’t need to live, and a way to notice and surrender any clinging. Reducing exposure does reduce the craving; but it has little to do with controlling dopamine.

DOES IT MATTER?? PERCEPTION AS METAPHOR

When I read or watch people talking about dopamine hits and crashes and tolerance, I translate it in my head to a message about avoiding having a conditioned response. They’re struggling to stop a compulsion or habit (craving a hit) and trying to avoid stimuli that provokes it (detoxing). That could just mean they want to doomscroll, and, instead, they put their phone in a drawer for the afternoon. So, does it matter if people think of dopamine as both the cause and solution to their problems?

Jungian analyst, Lisa Marchiano, recently said,

“If we think about myths as stories that are believed to be true by the culture that writes them, I would like to offer that the DSM is a cultural myth. … My favourite quote from [Jung’s] Collected Works: ‘We think we can congratulate ourselves on having already reached such a pinnacle of clarity, imagining that we have left all these phantasmal gods far behind, but what we have left behind are only verbal spectres, not the psychic facts that were responsible for the birth of the gods. We are still as much possessed today by autonomous psychic contents as if they were Olympians. Today they are called phobias, obsessions, and so forth; in a word, neurotic symptoms. The gods have become diseases’ [CW 13, par 54]. … Heaviness could be ascribed to Saturn. Being in a kind of frenzy could be assigned to Dionysus. And if it matches well enough, people can have that “Aha!” experience. And often, as I’ve seen in my practice, people can kind of exhale and place it into a certain aesthetic frame that gives them some distance between themselves and the problem that they’re suffering. Many different systems do that, by the way, but myth is one way of possibly doing that.”

Dopamine has reached god-like status, with some hoping to be granted its effects and others trying to be released from its chains. But this is a god we can see.

Part of the pull towards brain chemistry may be that we can see it with high-tech machinery in a way that feels like we can know the cause and effect. However, psychiatrist and neuroscientist, Iain McGilchrist, explained the current push to categorize and label and really pin things down can completely miss out on more right-brain attention to complexity and nuance. Just because we can see part of the brain light up doesn’t mean we understand what’s happening.

“What can be measured doesn’t matter and what really matters can’t be measured. It’s such a simple observation in a way, and it’s almost as if the culture has just taken one little simple wrong turn. … The small mistake is simply … the minute you get into a mindset … that if you can’t reproduce it in a lab, it’s nonsense … that in itself is such a kind of broken worldview.”

We think our psyche can be understood from the parts: neurons and chemical messengers, but that’s like picking apart a poem or work of art down to its constituting letters or colours to try to understand what it means. We need to see it as a whole, take it in, and feel it to really get it. We are so much more than the narrative of specific chemicals sending messages in our brain to help us survive.

McGilchrist says we’re currently living on Pinnocchio’s Pleasure Island:

“The people who create the technology are rushing us very very fast into this robotic left hemisphere world which takes us into goodness knows what horror. But they don’t see it as horror. They see it as utopia. … We sacrifice our freedom, our dignity, and everything to just being this consuming entity. … For a minute, [Pinnocchio]’s sort of seduced by this and has to learn the hard way that actually that is not going to be a route to anywhere that he wants to go, and it’s not compatible with being alive. … We completely mistake ourselves when we think that every kind of friction, every kind of opposition, every kind of restriction is something that should be done away with and is negative. Fulfillment is often something which doesn’t come unless you’ve overcome some kind of obstacle in doing it. And in doing so, you increase the capacity of what a human being can do, and certainly what you can do. … Suffering is part of what makes us fulfilled.”

Tech advances make things easy, particularly in how we fill our leisure time, but that leads to less pleasure. Effort isn’t the enemy. We want to stop our compulsion to scroll, in order to start a compulsion to go to the gym so we don’t have to make an effort to think about what we’re doing. But there are no quick fixes. It’s just us here, doing the work over and over and over to get back on a preferred path, which requires having a thought process around what we’re doing and whether or not we want to be doing it in the moment.

MYTH OF BEING UNAFFECTED BY THE WORLD

In a takedown of one “reward center” proponent, Stanton Peele said, “if you label things genetic, you are guaranteed some kind of audience, no matter how ludicrous your claims.” By “detoxing,” we’re already doing the things that help de-condition us: avoiding the external stimuli that provokes a response, but people prefer to think of it as a change in chemistry. Why do we prefer the dopamine story?

I wonder if believing we’re scrolling or gaming for hours is because of dopamine affecting us, removes our sense of responsibility for our actions. That might relieve any shame around it, which can feel great, but it also takes away our agency to actually change things.

Perhaps a different narrative that removes shame but keeps agency intact is to see these habits as conditioned by the toughest reward schedule out there devised by a technology that can beat a chess master. Of course we’re affected by it. B.F. Skinner identified this back in the 1950s. A variable ratio reinforcement schedule, getting a reward after a random number of behaviours, is *most *resistant to extinction. That’s why slot-machines create gambling addictions. One-armed bandits are stealing from you; it’s right in the name. Social media tricks us into feeling social and maybe saving the world with clicks, which add extra layers to wade through. It’s a more sophisticated thief stealing our time, energy, and focus for a company’s profit.

But people hate to believe they’ve been conditioned, as if we’re too smart for that nonsense. If we’re at the mercy of our chemical composition, that’s just unfortunate; by contrast, if we can’t stop because we’re been *conditioned, *then we’re an automaton, or of lower intelligence, or a simple animal, as if we should be immune to conditioning. Operant conditioning has been criticized for creating a mechanistic model of the self, as if believing in schedules of reinforcement usurps our free will, instead of a recognition that we are animals affected by the presentation of stimuli in our environment in a way that developed over millions of years. It’s necessary when we struggled to get food and needed something to drive us to seek it out relentlessly, and now it’s being exploited by corporations.

We like to think that it’s possible to be unaffected by our environment as if it’s a weakness to be affected by the world instead of a reality of our lives. Thinking of extinguishing the response by removing the stimuli and admitting the conditioning makes that more evident. Being affected by the world isn’t just seen as weak, it might also be kind of scary. It requires peeking over some defences that help us feel untouchable.

To feel stronger, some people might try to stop scrolling without changing their environment: with the phone full of fun apps and available all the time. That’s like trying to quit drinking with a fridge full of beer. There’s no shame in making it easier by getting rid of the triggering stimuli because this is notoriously a really hard reinforcement schedule to beat. Most of us can’t fully unplug from systems that have become the infrastructure of our daily lives, so we need help to stop once we start. We have more agency over the situation if we acknowledge what affects us and the work it takes to uncondition ourselves. It also means admitting that we are animals. But, like other animals, when rats lever pull for hours obsessed with their inconsistent rewards, they’re not bad rats! Rats don’t push levers because of any moral failing, but because they evolved to be wired to behave for survival now in a system in which this wiring is less than optimal. Even brilliant human beings are conditioned to do things, so it’s still not your fault, AND it’s possible to change.

Changing our environment is easier than hoping to change our chemistry. Granted it’s so much easier to extinguish the behaviour if the world changes the reward system for us, like schools that won’t allow phones in classrooms. Barring that, being aware of our thoughts helps to notice our perception of the rewards, which helps to minimize the potential reward or create distance from the thoughts instead of automatically fostering the cravings (don’t feed the fire!). We can also distract from the trigger, find an alternative that aims for less fleeting joys, set time limits and alarm, urge surf, recognize our phone as a slot machine, get a support group or friends to drag you away, promise to chat at a time you often get sucked into scrolling,… It can help to find something to care about outside yourself: instead of touching grass, plant something. There are lots of helpful apps and specific strategies. But it’s on us to do it.

Paying attention to be able to think before acting in order to slay our dragons is work, for sure, but it might help us to master that ancient skill of measurement. Once we firmly decide we don’t want to spend our free time lever pulling and scrolling, it’s still not easy to change, but it’s possible. But it requires removing the stimuli: a *device *detox.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.