- 10 Nov, 2025 *

When I first started working on the Lakelands, I planned to make my own system for it, until I eventually realized how much time that would take and how little I then knew about game design. I decided I’d be much better off using a pre-existing system and, after making a list of my requirements and researching various games, I settled on Fate Core, for a number of reasons.

- The Fate systems are in the Creative Commons, meaning I can use them freely without asking for anyone’s permission or shackling myself to a license more restrictive than Creative Commons Attribution.

- Fate Core, in particular, is the most mechanically robust (ie. “crunchy”) of the Fate games, which works better for my GMing style and, I think, the kind of experience I’d like Lakelands games to…

- 10 Nov, 2025 *

When I first started working on the Lakelands, I planned to make my own system for it, until I eventually realized how much time that would take and how little I then knew about game design. I decided I’d be much better off using a pre-existing system and, after making a list of my requirements and researching various games, I settled on Fate Core, for a number of reasons.

- The Fate systems are in the Creative Commons, meaning I can use them freely without asking for anyone’s permission or shackling myself to a license more restrictive than Creative Commons Attribution.

- Fate Core, in particular, is the most mechanically robust (ie. “crunchy”) of the Fate games, which works better for my GMing style and, I think, the kind of experience I’d like Lakelands games to be. Tables that prefer the lighter versions can still easily adapt everything here to Fate Condensed and Fate Accelerated.

- Fate Core is flexible enough that I can alter it according to my needs.

- Fate has a meta-currency that rewards making choices in character, and I love that kind of thing with all my heart.

- Fate has enough non-combat mechanics on the character sheet that you can use it to run games heavy in exploration, diplomacy, and crafting, while still allowing players to make combat-focused characters if that’s what they want.

- The website has explicit guidance for running horror games and, while the Lakelands setting is not only a horror setting, cosmic horror is central enough that such guidance is indispensable.

- I figured out a way to make aspects represent peoples. (In fact, I at first rejected Fate and looked at other systems because I didn’t initially see how I could make the different peoples work in this system. Only later did I figure it out.)

- I do like the customizability that aspects and stunts offer, though I worry they sacrifice a certain amount of clarity and reliability that I value in games. That’s a topic for another time, however.

However, Fate Core cannot work for the Lakelands as-is. That’s fine, of course. Throughout the Fate Core System book, it’s clear that Evil Hat Productions fully expects you to modify parts of the game, and they provide explicit guidance for doing so in the Fate System Toolkit. The rest of this post will outline those changes which apply to every Lakelands character.

The Peoples Aspect

As I’ve discussed this already in “Playable Peoples of the Lakelands,” a character’s people (what other systems might call “ancestry” or “kinship” or, erroneously, “species” or “race”) is represented as an aspect. I’ll repeat what I said in that post:

A Peoples Aspect would work like a normal aspect, and I have laid out ways to invoke and compel each of them to ensure that players and GMs are on the same page. Of course, these are not meant to be exhaustive lists; if players think of other ways to invoke or compel their peoples aspect that fits with the established lore of that people, they should be free to do so. These aspects also permit player characters to take certain stunts.

For example, the mundane human entry reads as follows:

You can invoke “Mundane Human” as a peoples aspect on rolls representing the following situations:

- long-distance running,

- throwing objects by hand,

- fine manual dexterity,

- and visual inspection in good lighting conditions of objects no more than one zone away from you.

Because of the last two situations, you can also invoke this aspect on any hand-eye coordination task in good lighting. However, this aspect can be used for compels in the following ways:

- to misidentify an object in low-light conditions,

- to fail to aim a gun, arrow, or thrown object correctly in low-light conditions,

- to overlook a threat because you could not smell its presence,

- or to perform poorly as a consequence of being too cold or too hot.

Two peoples-specific stunts are available to characters with the “Mundane Human” peoples aspect: Human Cultural Patrimony and Human Scientific Patrimony.

It is, I know, a little irregular in Fate to define so many ways that players can invoke or compel an aspect. Partly this is a question of my own habits and of my preference to make shared expectations explicit, both for my own comfort and for the comfort of others. But it’s also a response to playtesting: my players observed, quite rightly, that without much knowledge of who these different peoples are, it would be hard for them to know when and how to invoke their peoples aspect. Making this explicit gets everyone at the table on the same page.

Skills

Fate Core expects you to change the skill list. They say so explicitly: “When you’re creating your own setting for use with Fate, you should also create your own skill list” (“Default Skill List”). Here, then, are the Lakelands setting skills:

- Aesthetics - Covering all artistic performance, as well as knowledge rolls concerning art and art history

- Antiquities - Covering all knowledge rolls concerning pre-Arrival history, geography, and culture

- Athletics - As usual in Fate

- Burglary - As usual in Fate

- Crafts - As usual in Fate

- Deceive - As usual in Fate

- Empathy - As usual in Fate

- Fight - As usual in Fate

- Folkways - Covering all knowledge rolls concerning culture, law, politics, and religion in post-Arrival North America, and also the performance of certain occult actions

- Machines - Covering all attempts to use large machines in ways not covered by Crafts, such as driving vehicles or using jackhammers1

- Notice - As usual in Fate

- Physique - As usual in Fate

- Provoke - As usual in Fate

- Rapport - As usual in Fate

- Science - Covering all knowledge rolls about mathematics, the natural sciences, and computing

- Shoot - As usual in Fate

- Stealth - As usual in Fate

- Weirdness - Covering all knowledge rolls about the Weird, and the performance of certain occult actions

- Wilderness - Covering all attempts to navigate or survive in the wilderness, including most interactions with animals

- Will - As usual in Fate, and also covering the performance of certain occult actions

If you’re familiar with Fate, you’ll notice some absences. I removed Contacts and Resources not because I dislike them (in fact, I have come to quite enjoy them), but because neither makes much sense in the setting. It’s not clear what use Contacts will be in a world of tight-knit communities where everyone knows everyone, and where it is highly unlikely you will know anyone at all if you travel 100 kilometres or farther from home. The Lakelands has no common currency and while Resources could be used for barter goods, I think the post-apocalyptic genre so heavily involves scavenging, salvaging, and barter as tropes that I would prefer players actually engage in those activities at the table, rather than abstracting them away with a Resources roll. Lore is gone because I want characters to be able to specialize in kinds of knowledge: a person steeped in the occult may not know the first thing about science, while knowing the name and uses of every native plant will not help a traveller recall where the nearest pre-Arrival hospital was. Consider that post-apocalyptic fiction and cosmic horror alike trade on characters’ incomplete knowledge sets. Finally, I cut Investigate reluctantly, which I’ll get to in a moment.

You’ll also notice there are overall more skills than usual, twenty to the default list’s eighteen. There’s a reason for that. Consider this, from “Using Skills as Written” in the Fate Toolkit:

There are a couple of things to keep in mind here. First, if you subtract too many skills then the players might have access to too much of the skill list. If there’s too much overlap between PCs, you can wind up with PCs getting too little spotlight time. Conversely, if you add too many skills you might wind up with PCs who don’t have access to enough of the skill list, meaning they’re often missing a critical skill in a given situation.

The article presents that last possibility as a problem, but that’s exactly what I’m looking for. Yes, Fate is about “proactive, capable people leading dramatic lives.” This, however, is a weird post-apocalyptic setting: though the characters are capable, they must not be too broadly capable. In order to reflect the difficulty of survival in the Lakelands, I need to increase the difficulty of the game itself, and one way I’m doing that is by ensuring characters are proficient in an ever-so-slightly smaller share of skills. If a party finds they’re missing a critical skill in a given situation, that’s not a bad thing for a Lakelands game: they’ll be forced to improvise, finding an unconventional solution to a serious problem. That kind of improvisation is appropriate for a game with a scavenge punk element. (Alternately, they might need to deal with the consequences of their failure, which is not a bad thing in post-apocalyptic fiction, either.)

This brings us back to Investigate. I cut it in order to get twenty skills; with this number, a PC at character creation has a bonus in exactly half of all skills. That feels fair to me. Investigate is the one that got the cut because I think most of its functions can be recreated through a combination of roleplay and the other Skills.

Psychological Traits

Between dreamzones, spectres, and spellcraft, the Lakelands are full of phenomena that manipulate or make manifest a person’s inner psychology. To let GMs and players represent these strange effects in the game, Lakelands games mechanically abstract a character’s inner life as Psychological Traits. Each character has two basic fears, one manifest fear, one consolation, and one ideal. Of course, the players’ characters might not think of themselves this way – indeed, characters might even have incorrect ideas about their own anxieties and motivations – but it’s important that players and GMs both understand the PCs’ psychological make-up.

Basic Fears

Basic fears are the deepest anxieties that plague a character. Of all the psychological traits, these are the ones characters are least likely to recognize in themselves; however, they are also the most likely to be exploited by Weirdspaces and spectres. Although a character’s most personal terrors are as unique as they are, in Lakelands games they’re grouped into six basic fears:

- guilt,

- hollowness,

- injustice,

- isolation,

- suffering,

- and absurdity.

When making their characters, players choose two basic fears from this list to represent those characters’ fundamental anxieties. These are the ones that bother them most; the other fears might also besiege them from time to time, but not regularly enough that it has a mechanical effect. Players can choose the same basic fear twice, however; if they do, they’ll be less likely to encounter Weird phenomena that activate their basic fear, but it will be worse when they do.

Guilt. For some people, the worst thing about life is themselves. They perceive that they have some flaw that mars their character or their nature: maybe an appetite, or a hatred, or an inclination to respond the wrong way to every situation. Often such people experience this as a kind of guilt — not only guilt for some particular thing they’ve done, but also guilt for the way they are. Others might think of it as a kind of impurity or sickness rather than guilt, but the heart of it always comes down to the same thing: they have something wrong inside, and it’s part of them. As a consequence, such people usually fear judgement and feel as though they are hunted by accusers; this is true in a sense because, wherever they go, they accuse themselves.

Hollowness. Other people are most haunted by the sense that there is something inadequate about them. Most often they will feel underdeveloped, as though they have failed to fulfill some potential, but they might instead feel as though they have no potential, that some missing piece prevents them from ever becoming what they should have become. Perhaps they feel that circumstances did not allow them to grow into something they could have been in another time or place. Regardless of the details, they feel a shame not borne of guilt but rather borne of embarrassment. This embarrassment usually means they have a terrible fear of being perceived, and many of these people try desperately to disguise the emptiness they have within.

Injustice. For some, the main problem with life comes from society. Whatever terrors drive each member of a community, the resulting dynamic is a world of competition between various factions, with the stronger factions preying upon the weaker ones. History is thus the unfolding of violence and chaos. For such people, injustice is not just the lack of justice, the failure of history to set itself right; injustice (or chaos, or disaster) has an active presence in this world, felt in persecution, oppression, and fear. Of course, the anger that one group feels in response to that injustice can sometimes drive them to prey upon others whom they designate as scapegoats, making an eventual end to injustice hard to imagine.

Isolation. Other people are most troubled by what society does not provide. Such people can find no place for themselves among others; all social creatures feel an inherent need for community, and these people are most distressed by the sense that they might not have a place in one. This can take different forms. A person might already be isolated or they might be afraid that they will become isolated. A person might fear rejection by society or they might fear that their society is not adequate for them. Such a person might even preemptively isolate themselves because they cannot trust any group of people not to cast them out. However their fear is expressed, people such as these are most tormented by being alone.

Suffering. For some, the problem with life is simple: it is so full of difficulty, pain, frustration, and sorrow that it threatens to overwhelm a person. It’s almost too easy to say that life itself is the problem, but that’s not true: there are plenty of things in life worth celebrating, like laughter with friends and the pride of a day’s honest labour. What these people feel is that the world itself is out to get them and that ultimate victory against the world is impossible. All they can hope for is to survive, to endure whatever life throws at them for as long as possible. But then, hope itself leaves a bad taste in their mouths. They might be moved to hedonism or asceticism, incredible compassion or incredible selfishness. Regardless, the thing they fear most is that, one day, life’s tribulations will overwhelm them.

Absurdity. Other people are most undone by what existence lacks. They look at the world and are struck by what they don’t see: meaning, order, purpose, promise. Whatever they feel ought to fill that gap, the gap horrifies them. Or perhaps they feel that for whatever reason they cannot see what is truly there. Maybe there is a transcendent order to the universe and it is merely hidden from them. In this case, it is the fact that the order is hidden that distresses them. Whichever it is, and whatever they feel they should be able to perceive, it is the world’s seeming absurdity that most troubles them, and that leads them to feeling lost and perhaps even abandoned.2

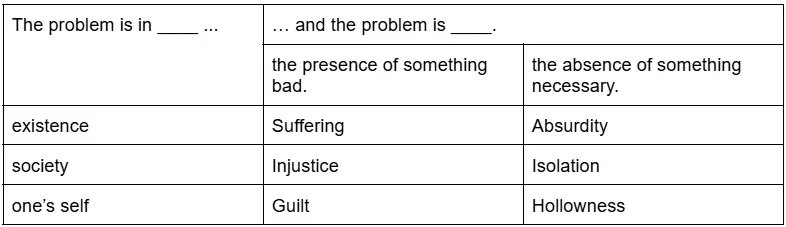

If it helps you to understand these basic fears better, they can be divided according to where each one locates the problem (self, society, existence) and what kind of problem each one thinks it is (the presence of something bad or the absence of something necessary). For example, while guilt is the presence of something bad in the self, hollowness is the absence of something necessary in the self and injustice is the presence of something bad in society.

A combination of two basic fears allows for a lot more variety. You’d need to figure out what that combination looks like for a particular character, but here are some examples:

Guilt + Hollowness. Adelaine (mundane human) worries that her habitual unkindness is a consequence of insufficient spiritual maturity. Although she’s not a Buddhist, she does have Buddhist friends who talk about crankiness and other vices as unskillful instead of immoral; that framing just makes her more stressed. She feels if she practiced virtue like she ought to, she would be kinder to the people around her. Of course, she’s pretty sure she’s not a good enough person to practice.

Guilt + Isolation. Fergusson (half-nymph) feared judgement and exile before the logging accident that made him a half-nymph, but it got worse after. He knows that the mould in his body could give his neighbours an excuse to send him on his way, so he is hypervigilant about his behaviour: he must be perfect, so that he never gives anyone a reason to use that excuse. Another person might not internalize that need for perfection, but Fergusson has: he believes that he probably does deserve exile and must keep that fact secret.

Suffering + Hollowness. Duke & Elroy (geminites) are cellists and singers in a well-known blues band that travels through the northwest Lakelands; though not the best-loved members of the group, they get their share of adoration wherever they go. A substantial part of their musical style comes from a deep pit of grief and dissatisfaction they cannot fill. Duke secretly craves the criticism he believes they deserve; Elroy is driven to become worthy of the praise he desires but does not feel they have earned.

Injustice + Suffering. Bromide (mould nymph) has had a difficult life: he came to consciousness alone in ogre-claimed ruins and spent days being hunted before he met a friendly face. Most of those first acquaintances were later killed by ogre-warped beasts. This intimate familiarity with terror and loss has not hardened him to the plights of others; indeed, he is especially furious on their behalf. He is pessimistic that anyone will build a city free of cruelty and inequality and he struggles not to give up fighting for the oppressed, but that deep anger keeps him at it.

Injustice + Absurdity. Although Gresa (drakemantid) was born on Earth, it still seems alien and foreign to her; the only way she can reconcile herself to this strange land is to rely on the Lidjetira faith her ancestors brought to this planet. The more tightly she embraces religion, however, the clearer it is that the city in which she lives deviates from good order and moral precepts. It is her life goal to wrestle the society around her into a shape that her ancestors would recognize as peaceful, just, and organized. Only when she has a community through which the universe’s hidden purpose is revealed will she feel at home.

Isolation + Absurdity. Cartju (new hominid) had a loving home where she was raised by her mother, her fathers, and her auntie, and yet as a child she always had nightmares that her parents would abandon her or that they would die and she would face the world alone, as an orphan, without anyone to explain how things worked. In adulthood she is quick to affection but just as quick to push friends away, scared of being alone and scared of being rejected; she treats religions and philosophies the same way, studying them with intensity and then abandoning them in disillusionment.

Manifest Fear

While basic fears are subtle, deep, and fundamental in a person, manifest fears are usually more concrete and much more obvious: spiders, public speaking, deep water, windstorms, and the like. A manifest fear can be anything at all, so long as the player can communicate it in a single word (“bears”) or short phrase (“being tied up”). Manifest fears will come into play much like basic fears; when a character encounters their manifest fear, they risk taking mental stress, and the Weird will often take the shape of a character’s manifest fear.

Although manifest fears can be straight-forward symbols of basic fears (a manifest fear of crowds representing basic fears of isolation and injustice), that isn’t necessary.

Consolation

No mind could continually endure the deep terrors that haunt it without some kind of solace. That solace does not negate whatever underlies their fears, but it does offer some promise that the sources of anxiety can be overcome or transformed into something good. The solace is a story, and a set of beliefs, and an attitude held in spite of everything; it is too nebulous and large and pervasive to have a mechanical representation. A character’s consolation, however, is something specific that especially reminds them of that solace: it could be an object, a place, a song or story, or an activity.

- When Adelaine feels too stressed about her own perceived insufficiency, she re-reads the stories of ancient Greek heroes, whose flaws were as great as their deeds. Consolation: an illustrated Pre-Arrival book of Greek heroes and myths

- Fergusson takes comfort most by getting out of his own head: he always feels much better if he has a chance to gather kindling and split logs. Consolation: preparing firewood

- Duke & Elroy take great satisfaction from their music, but it does not ease their nerves nearly as much as whittling does, at which they are terrible. Consolation: woodcarving

- Bromide’s furious despair calms when he rests under an elderly person’s roof, where he is reminded that survival is indeed possible. Consolation: the home of any person over the age of 60

- Gresa achieves clarity and serenity of mind while attending the local shrine of the Lidjetira faith. Consolation: the Lidjetira shrine of Gresa’s home city

- Cartju keeps on her person a toy from her childhood, inherited from her auntie, which she holds in difficult moments. Consolation: a small ceramic pony figurine

A PC can spend time with their consolation in order to heal consequences caused by mental stress or to end certain other effects. Like the manifest fear, a character’s consolation may have a logical or symbolic connection with their basic fears, but it does not have to: the mind is half-inscrutable, and the unconscious joins concepts in ways unknown to consciousness.

Ideal

People are more than just their fears and their comforts, of course; they’re also driven by virtues and taboos and personal expectations. Although a character may have a complex ethical code or a long series of rules of conduct, for ease of play each has one ideal that lies closest to their heart, the one that they are least willing to compromise even in the direst circumstances. Weird phenomena can manipulate (or, technically, be manipulated by) a character’s Ideal like any other Psychological Trait. An ideal can also be compelled somewhat like an Aspect, except that instead of paying a Fate Point to decline a compel, characters risk taking mental stress if they act against their Ideal. (They still gain a Fate point, though, if they create a problem when they observe their Ideal.) Ideals should be written as a noun or short noun phrase (two or three words). The following list of examples is not meant to be complete:

- Family Loyalty

- Group Loyalty

- Forgiveness

- Obedience

- Courage

- Personal Freedom

- Civic Duty

- Justice

- Equality

- Kindness

- Piety

- Hospitality

- Ritual Purity

- Physical Health

Fate and Other Systems

Although I’m focusing on Fate Core for now, it’s possible that I’ll decide to go another route. For instance, if I find that Fate Core doesn’t work for me or for the setting, I could put it aside and choose something else. But I also, sometimes, think about providing conversions: even if I still consider the Lakelands a Fate game, it might be fun to try writing the basics up in another system that I make available for players who’d prefer that. In the meantime, however, I’ll continue working on this setting under the assumptions that I’ll be using Fate Core.

To that end, I’ll also from here on out include these Psychological Traits in the example characters I provide. I’ve offered a few already, who lack these Psychological Traits because I didn’t want to confuse readers with unexplained character traits. Let me rectify that now.

Clark Sidhu, found in “Mundane Humans” Basic fear(s): Absurdity, Hollowness Manifest fear: wargs Consolation: preparing common medicinal herbs Ideal: Community

Haven and Liberty Braidwood, found in “Geminites” Basic fear(s): Injustice, Guilt Manifest fear: conflagrations Consolation: writing collaborative poems Ideal: Courage

Linnidt Ongenzeeld, found in “New Hominids” Basic fear(s): Isolation Manifest fear: clowns Consolation: her common-place book Ideal: Intellectual Honesty

As always for my Lakelands posts, everything in this post is provisional and subject to change.

So far I have been calling this skill “Machine Handling,” but it now occurs to me that “Machines” works fine and fits the one-word convention for skill names.↩ 1.

I based these fears on W. Paul Jones’s Theological Worlds, with my own substantial updates (such as the inclusion of Isolation as one of these basic anxieties). I played extensively with these ideas in a series of posts at a now-defunct blog of mine, Accidental Shelf-Browsing.↩

[#Fate Core](https://advantageonarcana.bearblog.dev/blog/?q=Fate Core) [#game systems](https://advantageonarcana.bearblog.dev/blog/?q=game systems) #post-apocalyptic [#the Lakelands](https://advantageonarcana.bearblog.dev/blog/?q=the Lakelands) [#the Weird](https://advantageonarcana.bearblog.dev/blog/?q=the Weird) [#weird fiction](https://advantageonarcana.bearblog.dev/blog/?q=weird fiction)