The Lumen Prize, founded in 2012, is a landmark award for artists working with technology. Over the years, it has established itself as a platform for modern pioneers pushing boundaries in the field. As Director Gillian Leitten observes, it is “not just an award, but a movement.” Recognisable names to have come through the prize include Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, known for her Pollinator Pathmaker project; Felicity Hammond, whose critical investigations into AI-generated imagery are touring the UK in 2025; and Refik Anadol, whose data visualisations have been exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and Museum of Modern Art in New York City. This year, the award received over 2,200 submissions from 71 countries. Ninety-nine finalists have been chosen across categories spanning still and...

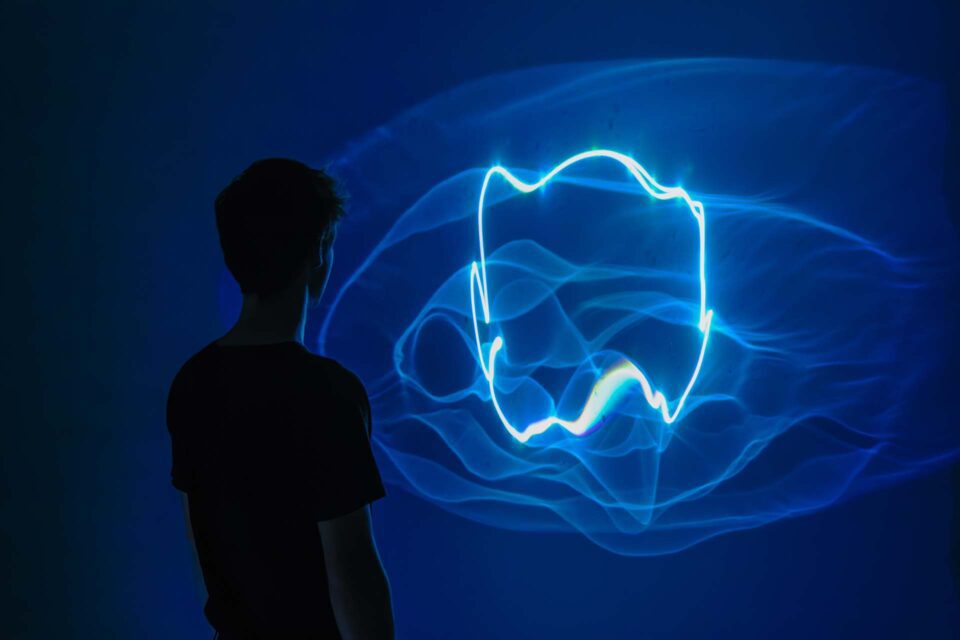

The Lumen Prize, founded in 2012, is a landmark award for artists working with technology. Over the years, it has established itself as a platform for modern pioneers pushing boundaries in the field. As Director Gillian Leitten observes, it is “not just an award, but a movement.” Recognisable names to have come through the prize include Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, known for her Pollinator Pathmaker project; Felicity Hammond, whose critical investigations into AI-generated imagery are touring the UK in 2025; and Refik Anadol, whose data visualisations have been exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and Museum of Modern Art in New York City. This year, the award received over 2,200 submissions from 71 countries. Ninety-nine finalists have been chosen across categories spanning still and moving image, performance, music, fashion, literature and beyond. From attempts to “break” ChatGPT’s predictions to garments mimicking coral reefs’ response to warming seas, the works resonate with the here and now. To view the shortlist is to be immersed in art that cracks the black box open and demands we peer inside. Amongst them is Lachlan Turczan (b. 1993), a finalist in the Hybrid category. The American artist has spent the past decade exploring the optical and sonic properties of water. He is interested in how the elements can influence human perception, and has exhibited at museums, design fairs, music festivals and experimental film screenings around the world. Most recently, Turczan premiered Lucida (I-VI) – new large-scale light works now selected by Lumen – alongside Google for the Milan Design Week in April. We spoke with him about Lucida and the broader scope of the studio’s practice.

A: You have been selected as one of this year’s 99 Lumen Prize finalists. What does this mean to you?

LT: It is a real honour to be chosen by the Lumen Prize, especially alongside so many artists who are working at the edge of art and technology. In making Lucida, I set out to capture fleeting natural phenomena and translate those delicate experiences into a museum context where they could be sustained and shared. To have this work recognised affirms that these quiet and often experimental explorations can resonate beyond the studio. It shows me that what begins as a personal investigation can connect with wider audiences and enter larger conversations about experiencing the world.

A: Could you tell us about your journey into the arts?

LT: I began my path as a painter, spending long hours exploring how colour and light could be layered on canvas. Over time, I realised that my real interest lay not in depicting light but in working with light itself as a raw material. This shift led me away from traditional painting and toward installations that could shape and choreograph light in space. Water became an early collaborator because of the way it reflects and transforms light. My practice has since grown into creating fountains, sculptures and immersive installations that invite audiences into direct perceptual encounters.

A: What is the role of technology in your artistic practice?

LT: I am interested in how we might reframe it so that it is not always something manufactured and imposed on nature. Instead, I look at how natural processes can themselves be understood as technologies of perception, carrying their own intelligence and ways of shaping awareness. By inviting audiences to engage with water, light and sound directly, I hope to spark curiosity and open a deeper sensory connection to the world around us. The idea is that technology can be found in nature if we learn to look more closely.

A: Lucida (I-VI) is the latest iteration of the Veil series. Where did the idea first come from?

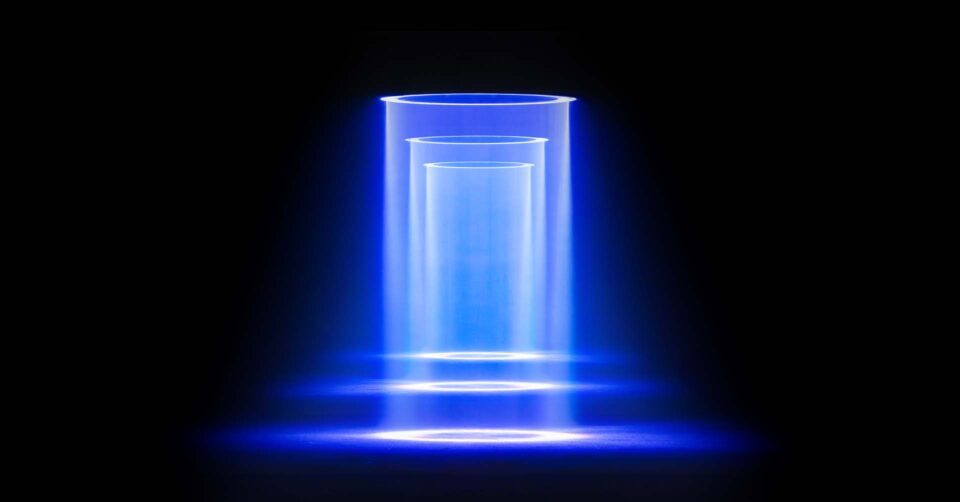

LT: The body of work began with a simple wish: to sculpt light as if it were a physical material. I discovered that water vapour could serve as a medium that reflects and bends light in surprising ways, often making it appear almost solid. This set me on a path of travelling to places where water shifts in phases, such as steam rising from geothermal springs or mist forming along coastlines. Each site became a laboratory for exploring how immaterial light could be given structure through its interaction with the water in the air.

A: How do the different locations impact the final results?

LT: I have created Veil in hot springs, coastal fog and in the dark, tannin-rich waters of southern swamps. Each environment transforms the work in its own way. The density of the air, humidity levels, wind speed, and even the subtle coloration of the water all alter how the light appears. Sometimes the atmosphere makes its seem solid and sharply defined, whilst in other places it feels diffuse and spectral. These settings are endlessly generative. Returning to the same site under slightly different atmospheric conditions can reveal an entirely new experience, reminding me that these works are co-created with the landscape.

A: What challenges do you face when installing a Veil?

LT: Working outdoors comes with constant unpredictability. A sudden gust of wind can scatter the projection into nothingness, whilst unexpected rain can short out delicate equipment. Batteries may run down in the middle of an experiment, forcing me to adapt quickly. At first, these challenges felt like obstacles, but over time I have learned to see them as part of the process. They heighten the sense of discovery because the results are never guaranteed. Each installation becomes an opportunity to listen more closely to the rhythms of the environment instead of trying to control them. This collaboration with natural forces is what makes the work come alive.

A: Lucida (I-VI) premiered with Google at Milan Design Week in April 2025. How was it received?

LT: Lucida (I-VI) represented a major step forward in the Veil series and took a full year of dedicated research and development. We engineered six-foot diameter lenses that could channel divergent light into a unified flow, giving it the presence of something almost material. Unlike the outdoor Veil, which are fleeting and dependent on the conditions of nature, Lucida sustains and choreographs light within an indoor setting. In Milan, audiences encountered the work with a kind of childlike wonder, pausing to take in the unexpected solidity of the light. Witnessing that response was deeply rewarding and confirmed that the experiment had reached new ground.

A: Can you tell us about some of your other artworks?

LT: Wavering and Seism both present sound as a sculptural tool. Each uses infrasonic frequencies to vibrate pools of water. In Wavering, a laser projector reflects off the pulsating surface, producing organic, ever-shifting patterns. The effect is remarkably complex and almost impossible to predict. These works show how sound can create form holistically, shaping an entire field at once rather than piece by piece. In contrast, the Veil works are more concerned with luminosity than audio. Veil relies largely on vapour or humidity to reflect light, but Wavering and Seism are actively shaping lakes and pools.

A: Water seems to be a recurring motif across all your work. What draws you to this element?

LT: I think it continues to pull me back because it acts as a mirror of change. It constantly shifts forms, moving between liquid, vapour and ice, and it bends and reflects light in ways that uncover hidden patterns. Water also responds directly to vibration, producing complex waveforms that reveal sound’s invisible presence. Each of these qualities makes it feel like a living collaborator across my bodies of work. Its unpredictably ensures that no experiment is ever the same twice. Each encounter is a reminder that perception is never fixed and can always be expanded – if we are willing to focus more closely upon the forces that are changing our surroundings.

A: Which artists or thinkers have influenced you? Who inspires you from the Lumen Prize shortlist?

LT: James Turrell’s explorations of light and perception were deeply formative for me. His ability to build entire internal spaces out of immaterial light opened up a path I continue to walk today. I have also found inspiration in scientific thinkers such as Sara Imari Walker, whose research into the origins of life reframes how we think about matter, information, and consciousness. From the Lumen Prize: Ivona Tau’s A Life Passed By stood out to me. Using AI to explore memory and family histories feels experimental and intimate – a thoughtful use of new technologies to probe human experiences.

A: Where do you see the field developing in future? And what are your thoughts on AI?

LT: I have long felt that if I relied only on tools created by others, my art would remain limited to what they had already made possible. That is why I strive to create my own instruments and develop a personal form of language. I am interested in the kinds of technology that emerge from the behaviour of matter itself, rather than those designed only for digital display. As for AI, I see it as one mechanism among many, useful when approached thoughtfully. What excites me about the future is seeing and encountering art that expands understanding and makes us look at the world anew.

A: What’s next for you – are you extending the Veil series, or moving in an entirely new direction?

LT: Both approaches are unfolding at once. I am continuing to develop new iterations of Veil designed for public spaces, where the works can interact with large audiences and varied environmental conditions. At the same time, I am also taking on large-scale commissions that combine custom optics, sound and architectural form. My goal with these projects is to create works that go beyond referencing nature and instead function as instruments of perception in their own right. I want these installations to offer fresh ways of experiencing our environment and ourselves, encouraging audiences to sense what usually remains invisible to them on a daily basis.

The Lumen Prize is at Kunstsilo, Kristiansand from 7-9 November: lumenprize.org

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

All images courtesy Studio Lachlan Turczan.

The post Shaping Elements appeared first on Aesthetica Magazine.