It was a thematic question of such relevancy that there was a whole panel dedicated to the concept itself, titled Let’s Talk Africa: What is it that binds the imagined continental whole? What does it mean to be African, a global citizen? Authors from South America and Africa discussed this over the course of an hour, the conversation spanning experiences of focusing on differences, external perception, and the audacity of doubt.

Yet the panel had too many people and not enough of a platform for everyone’s thoughts to be shared with cohesiveness. “You have a lot to prove—even on the map, Africa is smaller than it actually is,” Yamen Manai, a Tunisian author points out. Bitterness surfaces in his recollection: “Tunisia is a third-world country—I hated that growing up, I hated being fro…

It was a thematic question of such relevancy that there was a whole panel dedicated to the concept itself, titled Let’s Talk Africa: What is it that binds the imagined continental whole? What does it mean to be African, a global citizen? Authors from South America and Africa discussed this over the course of an hour, the conversation spanning experiences of focusing on differences, external perception, and the audacity of doubt.

Yet the panel had too many people and not enough of a platform for everyone’s thoughts to be shared with cohesiveness. “You have a lot to prove—even on the map, Africa is smaller than it actually is,” Yamen Manai, a Tunisian author points out. Bitterness surfaces in his recollection: “Tunisia is a third-world country—I hated that growing up, I hated being from a country of losers, having to prove yourself. To be African is to have to prove yourself.” From the nods of the half-dozen other panelists, it was apparent that this was a relatable sentiment. Yet the question of how it is that such a diverse continent cannot only find but hold on to threads of commonality as a collective, remained conceptual.

In late September, Nairobi hosted the seventh edition of the Macondo Literary Festival, themed “Chronicles and Currents.” This celebration of African and Black histories through literature, both fiction and nonfiction draws together writers from all across the continent—including the Caribbean and South America. The festival’s namesake comes from Gabriel García Márquez’s acclaimed novel One Hundred Years of Solitude. The fictional town is a manifestation of Latin American history, where prosperity, civil unrest, and imperialist exploitation chase after one another to no end.

Jonathan Bii has been a volunteer at Macondo for several years, assisting with program coordination and helping writers from across the continent and beyond settle in for the three-day festival. “This year’s theme was true to the core of what Macondo has been—introducing writers and authors to Macondo attendees, and by extension, to Nairobi,” he says. “And something I truly enjoy is learning about new authors, new regions and sectors.”

“Macondo has never just been about literature or books—it’s about ideas, imagination, thinking about our collective history, what solidarity looks like,” Bii continues. “Where we are [in history] right now—it has become very apparent that the Global North, Trump hunkering down on human rights, that people there don’t give a [fuck] about the South.”

The intended cruelty of President Trump’s sudden USAID cuts on the African continent illustrate Bii’s point—that the Western world’s connection to the Global South has always been imbalanced, with thousands of lives on the line when HIV clinics shuttered, demining activities halted, experimental drugs and medical devices left in people’s bodies. “Now that the guardrails we used to envision are no longer there, how do we prioritize each other, and what does that look like?” asks Bii. “This is the time to start looking to each other for the solutions we want to see, whether that’s through philanthropy, literature, organizing. It’s clear which countries have been putting us on their radars—namely, South Africa at the end of last year, speaking out about the abductions.”

For those even tangentially familiar with Kenya’s studded journey for international recognition, it should come at no surprise that even the Macondo literary festival has become another channel through which Nairobi vies for the status of “Global Africa”—a reality in which outsiders equate “Africa” with Kenya, if not Nairobi.

In preparing for this essay, I spoke to the people I thought should be the ones writing this story instead of me. I asked my friend April Zhu what she thinks about all this. She told me she recently had a conversation with someone about how Kenyans are the “Americans of Africa”—assuming they are the center, the quintessence of the continent, resulting in an overall shocking illiteracy about nations like Sudan, or worse, Ethiopia and South Sudan, their literal neighbors.” What Zhu shared reminded me of similar conversations I’ve had in the past. To bring the analogy home, pretty much anywhere not in the capital city is referred to as “upcountry” in Nairobi.

Nairobi is one of the most familiar (and therefore, least intimidating) African cities to many foreigners—Westerners in particular. This is reflected in specific Nairobi infrastructure, from modern highrises to rooftop infinity pools, but not what would be functional for the masses: sidewalks, bike lanes, public transportation, piped water. The city is also the African continent’s nesting place for international institutions and conferences, alongside tech and consultancy firms like Microsoft and Dahlberg.

Nairobi’s national theater.

Nairobi’s national theater.

But besides catering to the Global North’s developmental and investment priorities, there are several motivations to boost Nairobi’s not-insignificant literary scene (beloved by those who know it) further up the scale, to become the continent’s cultural and literary hub. This is despite how West Africa arguably produces more globally known authors, artists, and musicians, such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Amoako Boafo, and Burna Boy, respectively.

Even when faced by such rivals, Kenya remains undaunted, steadfast in pursuing its overarching goal—perhaps hazy but present, at least within certain spheres: a general conflation of Nairobi/Kenya with “Africa.” This is a phenomenon that William Kipchirchir Samoei Arap Ruto (Kenya’s fifth and possibly theleast popular president to date) encourages.

Journalist Samuel Kisika, author of the forthcoming book *Until Further Notice *(a work of political fiction on tribal-centered campus politics that mirrors Kenya’s national politics), views this aspiration to be known as “Global Africa” as transactional at best. “Ruto is similar to Trump,” he tells me. “He will see first, ‘What am I gaining?’ You can see this in how university funding is not subsidized the way it used to be, and also in the censorship. When looking at this government, that has been the narrative.” This should come as no surprise, Kisika continues. “After all, Ruto was nurtured by a dictator. “There should be an understanding of how this country should be led, and there just isn’t.”

It is important to note here that the Kenyan government has done nothing to encourage its own creative industry, instead passing laws taxing the creators as much as30 percent—and evenstopping plays earlier this year, recognizing the power that realities portrayed through art have to subvert. After all, Kenyan youth, monikered ‘Gen Z,’ have gained recognition on the continent and elsewhere as being excellent protest organizers, says Kuln’Zu, a Nairobi-based visual artist.

Politicians are not shutting down the cultural sector and playwrights as they did during the Moi era, targeting prominent, radical authors such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Daniel arap Moi served as Kenya’s second president from 1978 to 2022), says Tony Mochama, a journalist for The Nation and one of the authors at the Africa Union’s 60th anniversary. “But it’s almost like neglect: You won’t be beaten, but you will be malnourished. And [the government] will take credit for anything that comes out, they might even make a big deal about it.”

This year’s Mashujaa Day, celebrating the heroes that fought for Kenya’s autonomy, was the first year since independence in 1963 that the government recognized writers, says Mochama. “And that’s only because Ngũgĩ died this year, he was declared a posthumous hero. Across the board, there’s no grants for artists, strategies, nothing.”

As for Macondo itself, support for 2025’s festival came from the Colombian embassy in Nairobi, the Barbados High Commissioner, the Goethe Institut, Open Society Foundations, and even the luxury Fairmont hotel in Nairobi, amongst others, but not a shilling from the Kenyan government.

In contrast, when Mochama visited Accra, Ghana, in November 2022, as one of the five AU writers in residence at the Library of Africa and the African Diaspora, he was floored by the flourishing that is possible when the government invests in the cultural sector. “There are residencies for artists all year round, museums, treating culture as a living and breathing entity,” he shares. “You can see 60 years on, the fruits borne from Kwame Nkrumah’s work, (the first president of Ghana) who was a rapid promoter of culture. The top-down approach helps a lot. It only takes one person,” he says.

Meanwhile in Kenya, the ministry of culture and heritage has been the bottom of the barrel, the last in the class, since the Moi era. “The government would rather invest in large infrastructure projects so that they can get kickbacks from foreign entities, as government officials put money into Uber fleets and avocado exports, but feel zero obligation toward cultural projects.”

Kuln’zu agrees that the Kenyan government doesn’t take culture as a tool seriously. From a historical viewpoint, since independence from the British colonial administration in 1963, the nation has lacked a robust cultural ideology, a cohesive momentum toward a force more powerful than the extant reality. America once again serves as a good example here: “Freedom for all” is what the nation is built on. Although one would be hard-pressed to find serious individuals on either side of the political spectrum who truly believe this stance at this point in history, this ideology certainly proved effective.

Joaquim Arena, a journalist from Cape Verde and the author of Under Our Skin (a book weaving his Cape Verdean identity with the history of Portugal’s slave trade), believes that Kenya’s dynamic with the United Kingdom after colonization played a significant role in shaping its identity as an emerging Global Africa. This year’s Macondo is his first time in East Africa. “I do see Nairobi as a cultural and economic hub; it’s a well-developed and big city,” he says. “The idea we have of Kenya comes from the past, from literature and cinema. Now that I’ve come here, I can say exactly why. Kenyans are very curious about other writers, about me.”

Kenyans are very aware and proud of their history, the journalist continues. “When it comes to colonial heritage, they seem to have solved the problem and dealt with it much better than West Africa.” We discussed how ECOWAS countries have been kicking out military bases, abolishing the CFA franc, Ibrahim Traore and his completerejection of Western ideology in Burkina Faso.

History can explain a lot of things, Arena continues. “History also brings you self-confidence and experience. You see how these people, they come, but they will leave. This is your land. One day, you will be masters of yourselves. This reflects in how one interacts with the world, even in the 21st century.”

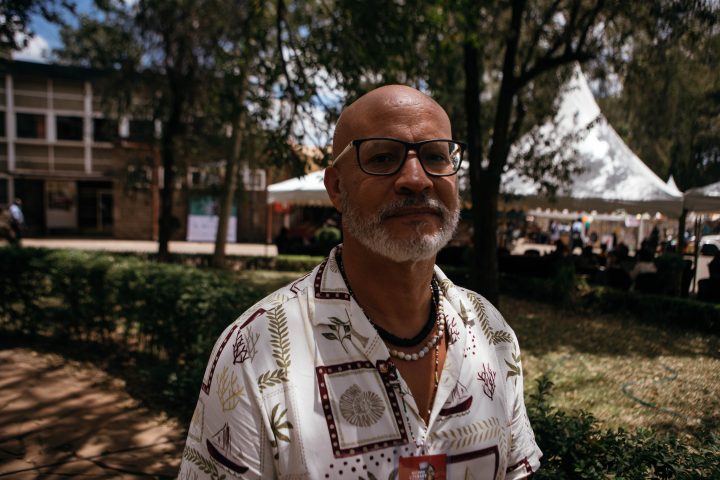

Author/journalist Joaquim Arena

Author/journalist Joaquim Arena

And so can geography. With Mombasa’s strategic positioning on the Indian Ocean, a conduit between East Africa and Indian and East Asia, its exposure to different cultures dates back centuries. Arena believes East Africa experienced much higher exposure to different non-African cultures than West Africa. “The Indian Ocean for centuries brought Arabs, Muslims—it’s like an open window to the eastern part of the World. West Africa did not have that; the Portuguese arrived only in the 14th century.”

There was also what all these visitors left behind. Kenya had something different from other colonized African nations, Arena explains. “The British invested a lot here, for instance, the railway from Nairobi to Mombasa. It’s clear how Nairobi has always been a very open city—the vibe and mood match it.”

In a way, Arena believes Kenya is already in a way Global Africa. Kenya’s talents and accomplishments are well seen around the world, such as in sports. “Even 40 years ago, seeing Kenyan athletes winning Olympic gold medals, it meant a lot to the rest of Africa. We saw their runners as having superpowers. There’s something very powerful about this.” Arena continues: “You can see the ambition in the cars, the buildings, how the country wants to be special. In Mali or Niger, the buildings are more traditional, giving off a sense that ‘this is how we are.’”

Writer ndegwa nguru, who works at Cheche, an independent bookstore in Nairobi, believes the city has all the right ingredients to position itself as the epicenter of Global Africa: “The city is alive with literary energy, young creators, and an undeniable creative pulse that refuses to be ignored,” he tells me. “But maybe we are not supposed to be mistaking excitement for permanence or assume that this cultural moment will be sustainable simply by being declared or acknowledged.”

In a 2025 UNESCO report on the African book industry, the numbers indicate a significant trade deficit. In 2023, the continent imported books worth an estimated US$597 million while exporting books to the value of US$81 million, constituting a staggering deficit of 76 percent compared with total trade. Kenya serves as an export leader yet remains tethered to European publishing houses, along with its regional counterparts in South Africa, Egypt, and Ghana. “As a result, Africa’s linguistic diversity is not well reflected in publishing: its 2,000 local and indigenous languages are largely overshadowed by English, French and Portuguese,” the report states. “This concept of Global Africa sounds powerful, almost even necessary, but it’s deeply flawed in its execution. Too often, the term gets weaponized as a branding tool rather than a genuine cultural transformation,” nguru says.

“There is an actual peril here,” nguru continues, “Not just in overhyping Nairobi’s potential, but in celebrating an Africa that is constantly being defined by external forces. Festivals like Macondo, while valuable in bringing together writers from all over the continent, risk becoming beautiful, fleeting moments disconnected from the real work of building infrastructure that nurtures both local and global literary ecosystems. Celebrating Global Africa is easy when you have the right venue, the right donors, and a bunch of diasporic names to throw around. But does this celebration come at the cost of creating an authentic and sustainable cultural space?”

Others echo nguru’s thoughts about the harsh reality of inequitable access to both ideological and economic resources, entrenched barriers within the literary and arts world, generally speaking. Kuln’Zu believes that the masking optics of this forceful desire to become Global Africa is a symptom of nationalism. “African nationalism has often produced everyday citizens who don’t talk about anyone else unless they live at borders. It’s a problem that’s not exclusive to Kenyans.” But at the same time, Kenya is forcing itself into conversations that it’s not a part of. “There’s an aspiration to be part of things, part of the West,” says Kuln’Zu.

In the end, the dream of Global Africa says as much about aspiration as it does about anxiety. Kenya’s cultural moment—visible in Nairobi’s skyline, its festivals, and its self-fashioning as the continent’s gateway—reflects both genuine creative vitality and the insecurity of a country forever performing its own arrival. The danger, as several writers at Macondo suggested, is that “Global Africa” becomes another development slogan, a mirror held up to the West for recognition rather than a platform for solidarity within the continent itself. For Nairobi, a city built on ambition and inequality in equal measure, the test is whether this cultural confidence can turn inward—toward nurturing local readers, local languages, and the infrastructures that make creativity ordinary rather than exceptional. Until then, the lights of Global Africa may shine bright, but they risk illuminating the same small circle of people who have always had access to the stage.