The latest US-East-1 outage sparked the debate around bare metal vs the cloud. We did the opposite in 2017. We went from bare metal to the cloud and it saved our company.

As Customer.io crossed $100m ARR, I was reflecting on our journey. The period of time when we were on “bare metal” almost killed us.

Our architecture drove our constraints

When we first started in 2012, we had a small budget of a few thousand a month for servers and almost no revenue, but big aspirations for the service we wanted to build. In order to confidently send messages triggered by what people didn’t do, we also had a non-negotiable requirement. We had to be able to process a firehose of data and no…

The latest US-East-1 outage sparked the debate around bare metal vs the cloud. We did the opposite in 2017. We went from bare metal to the cloud and it saved our company.

As Customer.io crossed $100m ARR, I was reflecting on our journey. The period of time when we were on “bare metal” almost killed us.

Our architecture drove our constraints

When we first started in 2012, we had a small budget of a few thousand a month for servers and almost no revenue, but big aspirations for the service we wanted to build. In order to confidently send messages triggered by what people didn’t do, we also had a non-negotiable requirement. We had to be able to process a firehose of data and not lose anything. If we had complete data, we could find needles in a haystack for our customers. For example: “find me all the people who visited the /plans page but didn’t complete the event ‘check-out’”.

This led us to distributed databases (MongoDB then Riak then FoundationDB) which needed high RAM, high CPU, lots of storage, and consistent performance. In theory, we could run them in a cluster and as our customer base grew, we would just add more servers. It would be possible to achieve high scale and fault tolerance.

Benchmarking bare metal vs the cloud

In our tests, servers from Hetzner vastly outperformed AWS and others for the money. I admit I was nervous about going against the trend at the time, but if I’m remembering right, it was about 1/2 the price for similar performance. So we paid for 12 servers and moved from Linode to Hetzner in 2012. Then as we grew, our customers complained the interface was slow and our API was slow when accessing the service from the US. So we moved again in late 2013 to OVH in Montreal, Canada. During our time with OVH until we left in 2017, we had up to 150 servers and spent $40k a month at our peak.

On bare metal we were plagued with problems that we would be insulated from if we were on one of the big cloud providers. Problems we haven’t thought about since moving back to the cloud.

What the cloud insulates you from (mostly)

The cloud pretends the challenges of physical infrastructure don’t exist. As the customer you shouldn’t need to wait for new hardware to be provisioned. You shouldn’t need to know which rack machine A is in relative to machine B.

As the number of servers grew, so did the number of things we experienced that caused operational headaches for our team and disruption to our customers.

The most memorable experience we had was when the main fiber line to our datacenter was severed where it crossed a bridge (the monseigneur langlois) along the St. Lawrence river. This put all routes to the datacenter on backup fiber that was immediately saturated and our “edge” data collection servers running on AWS east and west were unable to send data to be processed for a day.

In addition to that, we had an incident when someone else in a rack we had servers in was getting DDOSed and we couldn’t get traffic through that switch to talk to those servers.

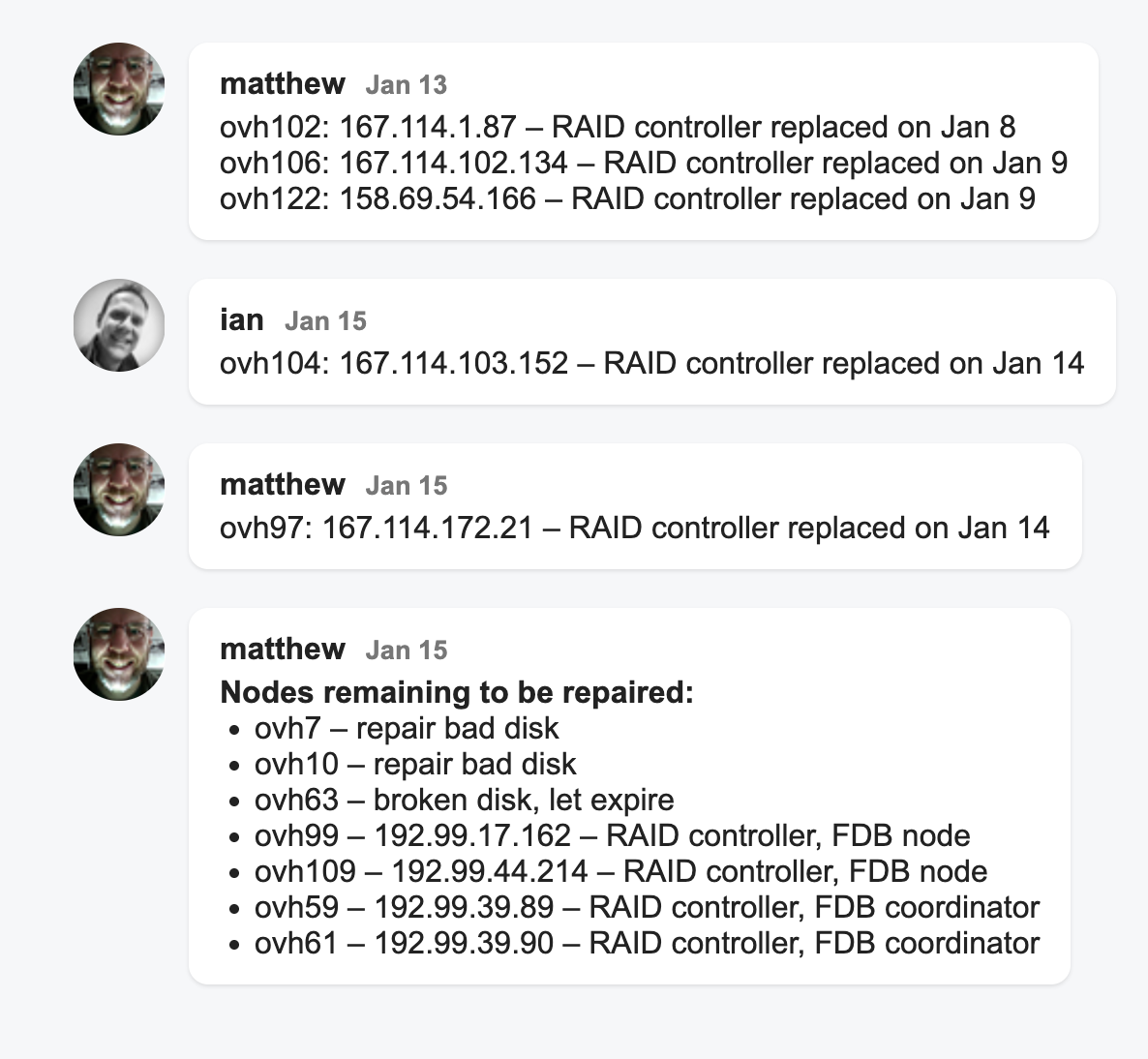

We then had a steady stream of RAID controllers failing where we would have to request the on-site techs replace the failed controllers. We had motherboard failures. RAM modules with ECC errors that needed to be replaced.

Every other day another failed raid controller.

Every other day another failed raid controller.

One time a transformer blew in the data center causing an outage.

When hardware failed, our distributed datastore was strained even further as it tried to replicate data while writing all the new data flowing in! Instead of being resilient, it felt like our service was fragile and any little incident would cause customer issues. My cofounder John and many early engineers were on call 24/7 and spending over 1/2 their time massaging servers and keeping the whole thing from collapsing.

The decision to rearchitect and go back to the cloud

There were two mistakes we made. First was that our system architecture made us fragile. Our customers didn’t benefit from being on a distributed database. Second was that if we didn’t need a giant database cluster, we could eliminate the “real-world” problems that we were experiencing so frequently being on bare metal. So we did. We had to rebuild our entire back end over a period of 2 years in order to migrate while keeping a fragile system running. It was a horrible period for our customers and the team involved in making this happen.

We completed our move to Google Cloud Platform in 2017 and today have over 1000 virtual machines, 2 petabytes of data storage across two regions and around $300k / month to run Customer.io. It would be operationally challenging for us to run the physical hardware ourselves. The amount of engineering time wasted from being on bare metal and the lost trust from customers far outstripped the gains in cost savings.

When the cloud makes sense and when it doesn’t

For services where you don’t know what you’re going to need a year from now and volume can be spikey, the cloud is great. It’s also possible to manage your costs so that you’re not overpaying for the flexibility you get.

Whatever you do, go into it with your eyes open and make a good decision based on the characteristics of the service you run and your business.

P.S. The server hosting this blog post is running on a Minisforum MS-A2 in my basement