Yorgos Lanthimos, the filmmaker known for stylized, pitch-black comedies rife with disfigurement, deadpan dialogue, and transgressive gamesmanship, is an acquired taste. Hollywood acquired it a few years ago, catapulting the Athenian from art house infamy to global celebrity with *The Favourite *(2018), followed by *Poor Things *(2023) and *Kinds of Kindness *(2024), and the newly released *Bugonia *(2025), all of which star Emma Stone (she insists that he’s *her *muse, not the other way around).

His experimental spirit undiminished by mainstream success, Lanthimos has recently branched out to a new venture: the photobook. Although the images in *Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken *(Void, 2024) and *[i shall …

Yorgos Lanthimos, the filmmaker known for stylized, pitch-black comedies rife with disfigurement, deadpan dialogue, and transgressive gamesmanship, is an acquired taste. Hollywood acquired it a few years ago, catapulting the Athenian from art house infamy to global celebrity with *The Favourite *(2018), followed by *Poor Things *(2023) and *Kinds of Kindness *(2024), and the newly released *Bugonia *(2025), all of which star Emma Stone (she insists that he’s *her *muse, not the other way around).

His experimental spirit undiminished by mainstream success, Lanthimos has recently branched out to a new venture: the photobook. Although the images in *Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken *(Void, 2024) and *i shall sing these songs beautifully *(MACK, 2024) were taken during the making of *Poor Things *and Kinds of Kindness, respectively, these books are far from simple behind-the-scenes companion volumes. Instead, they allude to their own narratives and worlds, hovering somewhere between photography and cinema. Below, the director talks about how these books came to be, and what might come next.

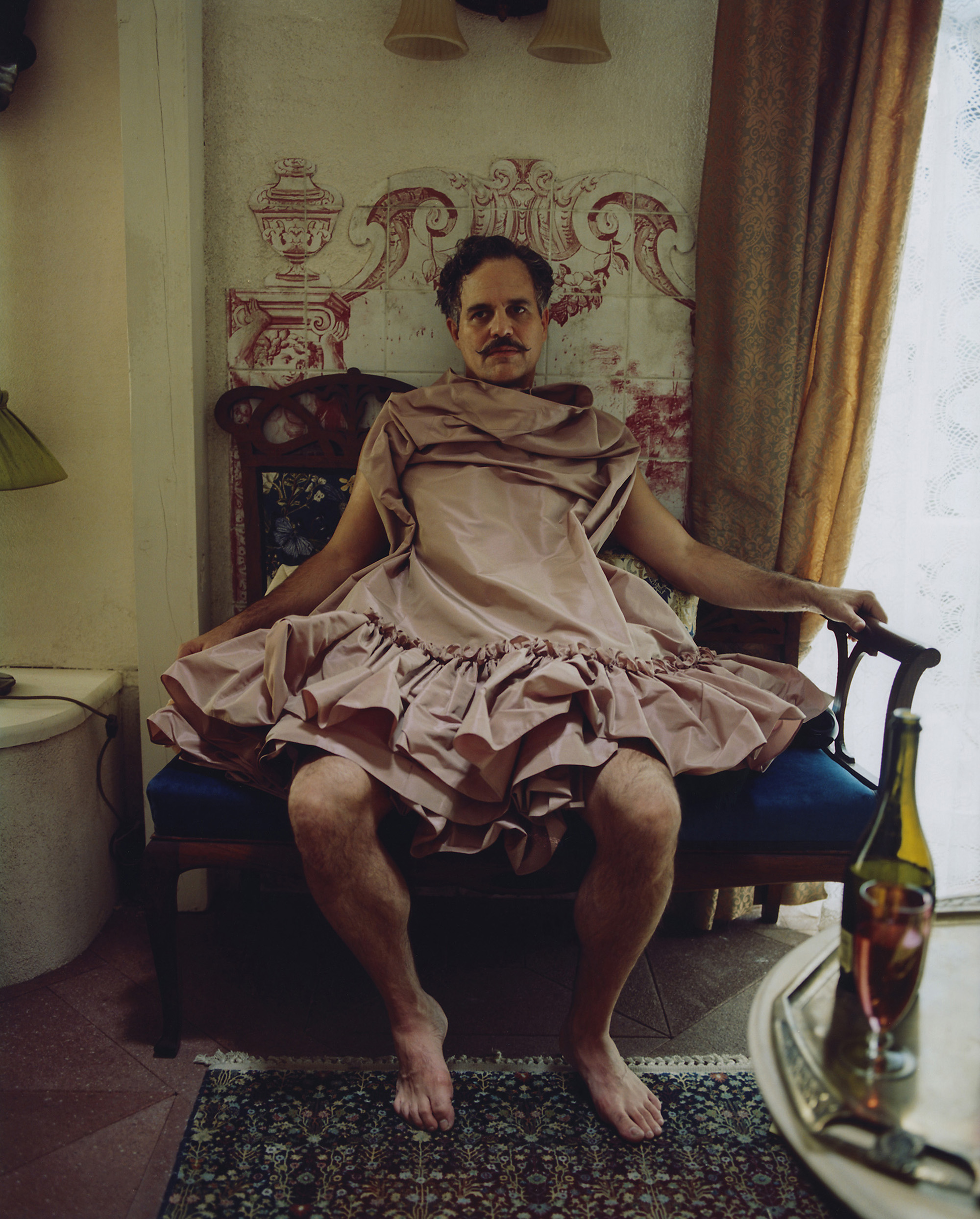

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024) © the artist

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024) © the artist

Zack Hatfield: When did your interest in still photography begin?

Yorgos Lanthimos: I went to film school when I was nineteen. I bought a camera and started taking pictures randomly, without any purpose. This was in the ’90s, before the internet. I was looking at Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Stephen Shore, the classics. When I started making movies, I began taking pictures on set. I’m very shy when it comes to approaching or photographing people I don’t know, so this felt like a more normal, accessible thing to do. I’ve become more drawn to photography, in general, in the past few years. I even built my own darkroom next to my editing room, in Athens.

Hatfield: For years, you’ve enlisted the photographer Atsushi Nishijima to document the making of your films. But your own images are up to something else. They’re autonomous artworks, existing both inside and outside those cinematic worlds.

Lanthimos: The beautiful thing about photobooks is that they often allow for a story that’s not tied to the conventions of narrative. With Dear God, I didn’t want to make something that was in addition to Poor Things, but something that could stand on its own. Even more so with the second book. When I was making Kinds of Kindness, shot on location in New Orleans, it was already in my mind that I was taking pictures that weren’t necessarily related to the film. In the book, there are all these details that you’ll never get a sense of while watching the movie.

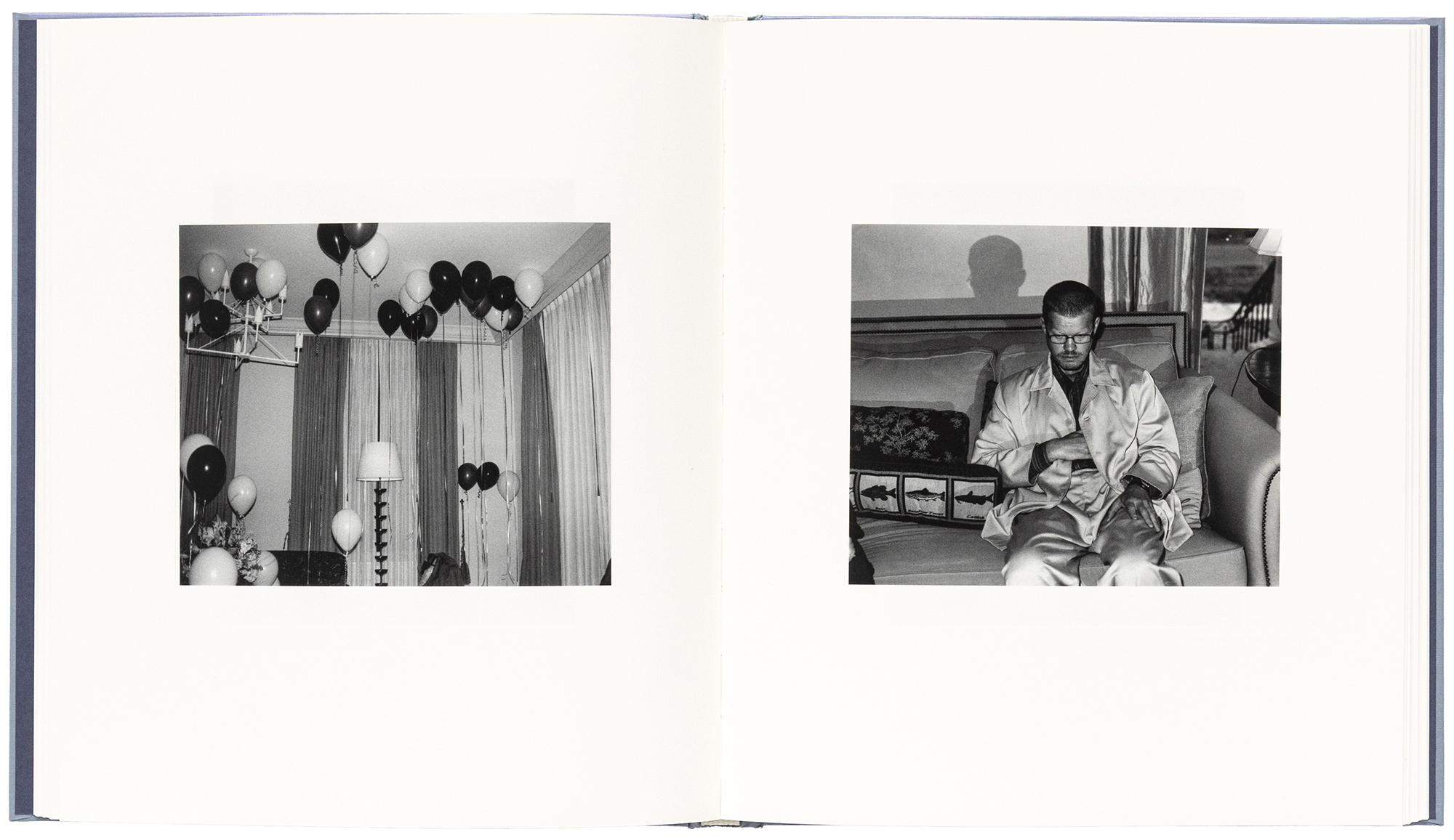

Interior spread of Yorgos Lanthimos, Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024)

Hatfield: ***i shall sing these songs beautifully *feels more classical, whereas Dear God makes use of double gatefolds, which often reveal evidence of artifice—rigs, scaffolding, boom stands, cycloramas.

Lanthimos: I love how different the books are. Michael Mack hadn’t seen the *Dear God *book when we began the project, hadn’t seen a lot of my pictures. I showed him Dear God, and he said that the *Kinds of Kindness *book needs something different. The first book is a very complex, designed book. The second one includes way more black and white, a lot of flash. I wanted to make a more traditional photobook, in a more American tradition. And I wanted to create a narrative that has a more mysterious relationship to the pictures, that exists more in the gaps between pictures. At Michael’s suggestion, I added some of my own fragmentary texts. I would look at a photograph and let random thoughts, observations, and experiences take over. There’s one little text that is inspired by an R. D. Laing *Knots *type of style and structure. That’s a book I love.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Description

Subscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Yorgos Lanthimos, Untitled, from Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken (Void, 2024) © the artist

Hatfield: Can you talk about the role collaboration played in creating the books?

Lanthimos: It was very liberating to work with these other people, Myrto Steirou and João Linneu of Void and then Michael at MACK. I relied on them because it’s not a process I’ve done before, sequencing a photobook. There is some overlap with how you edit a film with images, but it’s so much freer. It feels like there are fewer rules tied to conventional narrative.

Hatfield: How did the actors help you make these pictures?

Lanthimos: The experiences were quite different. *Dear God *was a very particular experience. We were in Hungary in huge film studios surrounded by sets. I used a large-format camera to make all those black-and-white photographs, and medium format to make the color portraits. Photography became a punctuation in between scenes. It was called “portrait time.” Whenever I had a few seconds between setups, I shouted, “Portrait time!” and brought out the large-format camera. Sometimes, Atsushi would see that I was frustrated with something that didn’t work while trying to film a scene and would suggest to me, “Portrait time?” I tried to do it really fast, which, of course, is counterintuitive with a large-format camera. At the same time, it was this little bit of frozen time within making a film and performing. It was a kind of game that we enjoyed.

Interior spread of W: The Art Issue (2023)

Interior spread of Yorgos Lanthimos, i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024)

Hatfield: I read that Emma Stone helped you develop the photographs in the bathtub of a Budapest hotel.

Lanthimos: Emma got really interested in the process of loading film and processing the negatives, even though she has no interest in taking pictures. She likes the technical aspect of printing. She basically printed the black-and-white photos for a project we did for *W *magazine. I don’t know how we had the strength to do it—after a whole day of filming, twelve hours, going back to the hotel room, processing film and scanning it. But it really *gave *us strength. It helped us forget about the stress of filmmaking. You get the result of it immediately: “Look, we just processed this portrait that we got this morning, and we’re looking at it!” Or, “We fucked it up and scratched it, but it’s still beautiful.” It enriched our experience of making that film.

I take pride in having gotten a lot of people shooting film again. Jesse Plemons, who starred in Kinds of Kindness, has become an obsessive film photographer. Will Tracy, the writer on Bugonia, the new film we just shot, has taken up film photography. He goes out and takes night pictures with a tripod. I think my excitement about photography is a little contagious.

The beautiful thing about photobooks is that they often allow for a story that’s not tied to the conventions of narrative.

Hatfield: Are other artists’ photographs and photobooks important to your creative process? I noticed that Richard Misrach’s 1983 photograph Diving Board, Salton Sea, from his 1987 book, Desert Cantos, was cited in the credits for Kinds of Kindness.

Lanthimos: I have been moved over the years by many photographers. I think that in itself is a great influence, without necessarily being a visible, obvious one. I love the work of Sage Sohier, Mary Frey, Chris Killip, Rosalind Fox Solomon—her latest is a very powerful, moving masterpiece—Mark Steinmetz, Robert Adams, Lee Friedlander, Larry Sultan, Alec Soth, Gregory Halpern, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Masahisa Fukase. I can go on forever. I really loved Melinda Blauvelt’s book. Michael Mack introduced me to Lewis Baltz only recently. I was gifted an incredible book, *Sex. Death. Transcendence. *(2024) by Linda Troeller. Paul Graham’s *a shimmer of possibility *(2018). Whenever I look at it, I tear up.

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024) Courtesy the artist and MACK

Yorgos Lanthimos, from i shall sing these songs beautifully (MACK, 2024) Courtesy the artist and MACK

Hatfield: It’s hard to think of other photobooks that merge cinema and photography in such an open-ended way. Do you know about Annie on Camera?

Lanthimos: What’s that?

Hatfield: In 1982, John Huston invited nine photographers, including William Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz, and Stephen Shore, to take images on the set of Annie. It’s great.

Lanthimos: I’m writing that down.****

Hatfield: Do you consider a particular audience for your photobooks?

Lanthimos: Not really. I don’t think I could try to make something for an audience. You do something you want to make or see, and then you hope for the best.

Hatfield: Right now, you’re editing Bugonia, a sci-fi satire. Did you have another book in mind while filming it?

Lanthimos: I’m not sure. It’s a very contained film, so it might be harder to make a photography book that can feel independent from the film and strong in its own right. I’m trying to concentrate more on doing photography which is not film related. Lately, I’ve been taking landscape photographs in my travels around Greece, but also in Athens. I want to start taking more portraits but I need to ask people, so I’m very slow at it, procrastinating. Hopefully at one point I’ll make a book that’s not related at all to one of my films.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue,” in The PhotoBook Review.