T

There are times when the air is so thick with words and images that a person can hardly breathe. Max Picard wrote out of such a time. Born in 1888, this Swiss physician turned philosopher lived through the convulsions of two world wars and wrote from a land that prized neutrality but could not escape the din of a century intoxicated with its own machinery. In 1948, with Europe still smouldering from devastation, he published The World of Silence. It was an attempt to rescue an element as indispensable as water or air, without which human beings become less human. Civilizations, too, become less human when they lose silence.

“Silence,” Picard observed, “is nothing merely negative; it is not the mere absence o…

T

There are times when the air is so thick with words and images that a person can hardly breathe. Max Picard wrote out of such a time. Born in 1888, this Swiss physician turned philosopher lived through the convulsions of two world wars and wrote from a land that prized neutrality but could not escape the din of a century intoxicated with its own machinery. In 1948, with Europe still smouldering from devastation, he published The World of Silence. It was an attempt to rescue an element as indispensable as water or air, without which human beings become less human. Civilizations, too, become less human when they lose silence.

“Silence,” Picard observed, “is nothing merely negative; it is not the mere absence of speech. It is the phenomenon of the whole man.” He distinguished between original silence, the primal quietude woven into creation itself, and the provisional silences we stumble into in modernity, the pauses between bombardments of sound. One, creative and life-giving; the other, destructive, masking emptiness. Picard contrasted the unbroken quiet of mountain valleys with the incessant buzz of modern cities, where engines and horns fill every crevice of time. He feared that when language is no longer sheltered by silence, it loses its savour, collapsing into chatter. Without that holy hush, words become mere signals. Relationships, too, suffer, for without shared repose there can be no true listening.

The age of the telegraph and the wireless already threatened to banish this original silence. What would he say now, when we carry the factory whistle in our pockets, when algorithms call out to us day and night, when even dreams are colonized by notifications? His intuition remains bracing: without a surrounding quiet, language grows thin, judgment hardens into argument, and intimacy withers. The word that has not been sheltered by calm arrives brittle, even when it means well. It shatters at first use.

The poets anticipated this hunger. Stéphane Mallarmé, writing decades before Picard, had already intuited that silence was essential to meaning. His revolutionary poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A throw of the dice will never abolish chance), first published in 1897 but perfected in its 1914 edition, scattered fragments of text across double-page spreads, allowing white space to dominate. The poem unfolds like a score: typography itself becomes meaning. Words float in a sea of quietude, connected by rhythm and pause. When he writes, “JAMAIS / N’ABOLIRA / LE HASARD” (NEVER / WILL ABOLISH / CHANCE), the line breaks themselves speak. Gaps on the page mirror the cosmic gaps the poem contemplates. This was a metaphysical gesture: absence as revelation.

Mallarmé’s Tuesday-evening salons in Paris gathered symbolists, musicians, and painters who likewise sought to push against the tyranny of naturalism. For them, quietude was a halo. In his earlier sonnet “Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui” (The virgin, vivacious and beautiful today), the white swan caught in frozen water becomes an emblem of speech striving toward silence, of song that longs for its own vanishing. Mallarmé once remarked to Degas that poems are made with words, not ideas, which is a way of saying that placement matters and that tact does the work that force cannot do. The unprinted field can be reverent. It can protect what ought not be handled directly.

His lifelong ambition, as he once declared, was “to give a purer meaning to the words of the tribe.” Purification meant arranging words amid stillness so they could be transparent to mystery. Later poets would take his lesson to heart. T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and Paul Celan’s fractured lyrics are incomprehensible without Mallarmé’s spacing. Even their cadences carry echoes of liturgy, where pauses preach as powerfully as words. To read Mallarmé attentively is to feel poetry approach prayer.

The mystics had already lived this lesson. Pseudo-Dionysius taught that God is beyond every name, beyond even being, so language must proceed by negation until quietude itself becomes praise. Meister Eckhart spoke of Gelassenheit, a letting-be in which the soul consents to emptiness, entering the “desert of the Godhead” where no word can follow. Nicholas of Cusa described a learned ignorance, docta ignorantia, that bows before mystery rather than presuming to master it.

Angelus Silesius, the German mystic and poet, sang the same wordless hymn in his seventeenth-century verses. For him, prayer was a return to the root of being: “True prayer requires no word, no chant. . . . It is communion, calm and still with our own godly Ground.” His brief, crystalline aphorisms teach that silence is the condition in which Love can be born anew. “If in your heart you make a manger for Love’s birth, then God will once again become a child on earth.” In this sense, silence is less a void than a cradle, an emptied chamber of the self where divinity may alight, tender and unannounced.

Elsewhere, he counselled, “God far exceeds all words that we can here express; / In silence He is heard, in silence worshiped best.” With these words, Silesius anticipates the monastic intuition of Thomas Merton: “The more the soul is still, the closer God is near; the less it claims for itself, the more His light shines clear.”

This vision finds an echo in the teaching of ʿAlī Hujwīrī, one of the earliest Sufi masters, who described dervishhood as “a metaphorical poverty.” The dervish, he observed, is not a traveller pressing his own wilful path but a clearing through which something passes. To be such a vessel is to embody silence itself: to yield, to relinquish, to stand transparent before the Eternal. Where the ego falls silent, another speech is overheard: the murmuring of the Beloved, the light that shines when the self no longer obstructs its passage.

The Hesychast monks of Byzantium guarded the Jesus Prayer with their breath until calm and word became indistinguishable, keeping the Name with inhalation and exhalation until prayer was as simple as breathing. In Sufism, Rumi captured the same paradox: “Silence is the language of God; all else is poor translation.” ured mauna, sacred silence, as a spiritual discipline. Zen masters answered questions with a bell or a gesture, teaching that the finger pointing to the moon must not be mistaken for the moon itself.

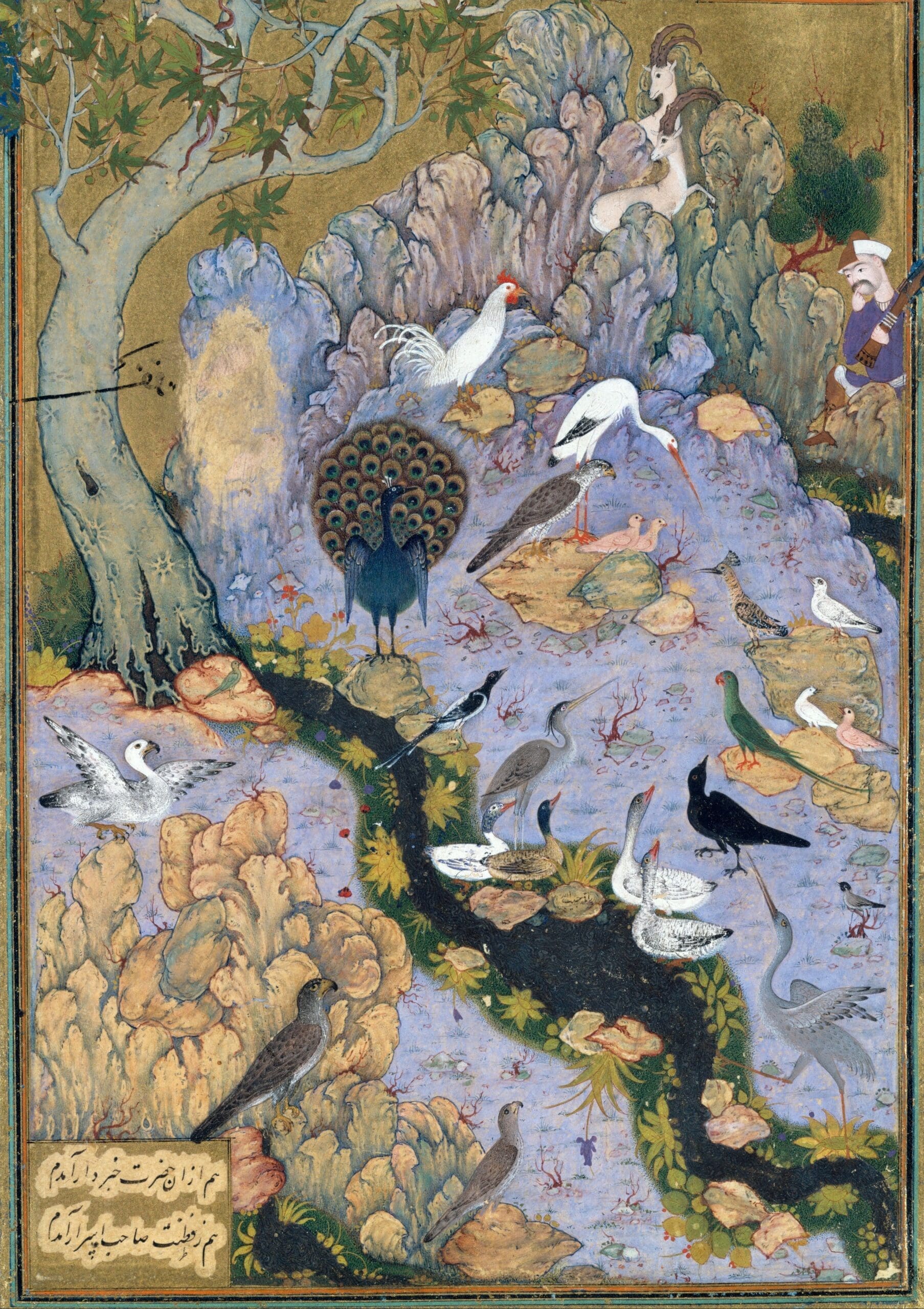

Folio 11r from The Concourse of the Birds, by Habbiballah Savaji, circa 1600. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Modern contemplatives inherit this stream. Merton distills the matter: “The deepest level of communication is not communication but communion.” There is a register where information fails and yet understanding is possible, even abundant. Two people at a deathbed know this. A mother holding a sleeping child knows it. Henri Nouwen insists that ministry begins beyond speech, in presence. Across traditions, silence emerges as the condition for encounter. Without it, words become untethered from reality; with it, language finds its home again.

Mystical quietude differs from aesthetic calm: past a literary technique, it is an existential practice, a schooling of desire and attention. The silence of the mystics baptizes speech, allowing language to be born of awe.

Philosophy, when it is patient, arrives at the same clearing by its own methods. Pascal’s severe observation that humanity’s miseries stem from our inability to sit peacefully in a room is less an indictment than a diagnosis. Restlessness keeps us from the inner meeting that would set our priorities in order. Heidegger insists that authentic speech grows from Hören, the receptive listening that precedes assertion. Levinas locates the command not to kill in the silent demand of the face, where obligation precedes language. Wittgenstein, having mapped what could be mapped, closes his Tractatus with the sentence that has become proverbial: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Simone Weil sees attention itself as a form of prayer, a still gaze that resists both distraction and domination. It is a trained willingness to receive what is there, rather than to project what one wishes to be there. Maurice Blanchot reflects on “essential solitude,” where the self grows inaudible so that writing may be overheard. Each of these thinkers, in their idiom, points to quietude as guardian of conscience. They differ in method but share a posture: bowing toward what exceeds our explanations.

Artists have embodied what philosophers and theologians articulate. John Cage’s notorious 4′33″ instructs performers to remain mute, revealing that the room itself is already singing: shuffling feet, a cough, a door creaking open. At first audiences felt tricked. Then they heard chairs whisper, programs rustle, breathing settle. Music had not been taken away; it had been restored to the world. Morton Feldman extends notes until they nearly dissolve; Arvo Pärt’s tintinnabuli style makes bells out of quietude.

In the visual arts, consider ur becomes climate. Speech has no authority there. Bodies learn to be present without comment. A person can sit and feel that something is allowed to arrive that would be scared away by insistence.

Interior of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas. Image: creativecommons/Alan Islas.

Architecture, too, can school us in silence. The Japanese speak of ma, the meaningful interval that allows form to breathe. A chapel by Tadao Ando or Peter Zumthor can feel like a lesson in such intervals. Concrete, light, and shadow do not compete; they consent to one another. The result is an austere hospitality that receives the visitor, unceremoniously. These spaces use shadow and interval to preach without words.

Film has its liturgists of quietude: Tarkovsky’s long takes, Bresson’s restraint, scenes where nothing happens but the soul is schooled to expect revelation. Even the tea ceremony becomes an art of structured calm, where every gesture unfolds in contemplative rhythm.

Our century multiplies Picard’s concern exponentially. Social media rewards speed, assertion, and outrage. Scholars describe “continuous partial attention,” a state where nothing receives depth. Linda Stone coined the phrase to describe the condition of perpetual distraction that fragments consciousness itself. Studies of noise pollution reveal its measurable toll: elevated blood pressure, disturbed sleep, impaired learning in children. We flee into digital detox retreats, or into apps that sell quietude back to us as a subscription service. Noise is the religion of our age, demanding constant sacrifice of our attention.

Yet silence is a human inheritance. It is the ground where thought clarifies, where prayer ripens, where friendship deepens. Even politics needs stillness: Václav Havel described the power of the powerless as a refusal to participate in lies, a silence that carried more truth than many speeches. That refusal was costly; the person had to live by the truth without requiring a hearing. The moral strength of such a stance comes from the same source as contemplative practice.

There is a risk in praising stillness: reticence can be weaponized as censorship or cultivated as resistance. To those initiated in subtleties, there are countless forms of quietude. The refusal to shout may be an act of dignity. In trauma, silence can signify unspeakable suffering, yet also the possibility of healing beyond words.

The Macedonian poet Aco Šopov gives voice to this paradox:

If you carry with you something unsaid, something which pains and burns, bury it within the depths of silence— the silence will say it for you.

Šopov’s lines remind us that silence does not merely absorb anguish; it can articulate it obliquely, preserving what words cannot safely hold. One can distinguish between silences that break trust because they protect cruelty, and pauses that make space for a bruised voice to gather itself. The first destroys; the second heals.

Silence also heals in ways neuroscience now confirms. Periods of calm allow the brain’s default-mode network to restore itself, consolidating memory, repairing synapses. Trauma therapists know that not all wounds can be narrated; sometimes the most faithful presence is silent witness. Grieving families often remember not words but companions who sat with them in unhurried repose.

Restorative-justice circles make space for victims and offenders to listen across divides, where quietude is as important as speech. Music therapists use pauses as instruments of recovery. The work quietude performs is subtle but steady: it threshes wheat from chaff, desire from distraction. It teaches us to speak more slowly, to choose words as though they mattered, to withhold judgment long enough for truth to ripen.

If we lose the capacity for such refusals, we will live entirely in reaction. Screens will time our sentences. Our prayers will become monologues addressed to ourselves. We will suffer the peculiar exhaustion of people who are always performing and never present. The tragedy is that the human animal is well suited to awaken attention. Children, when left unharried, will pause before a beetle and study it like a jeweller. Adults can relearn this, though it requires unlearning the attitude of perpetual commentary.

If culture is to be restored, acoustics matter as much as laws. Cities can be designed to give relief from the drone; parks can be protected from amplified intrusion; liturgies can remember that awe dislikes haste and that the space around a reading may preach more persuasively than a hurried homily. At the personal level, modest vows are possible: Rise and let the first half hour belong to stillness. Walk without headphones. Keep an hour of shared quiet each week. End the day by returning to stillness what was said in haste.

Monastic abstemiousness is possible outside the monastery—necessary even to jealously guard our inner lives from the violence of modernity. These are habits that return us to scale. They empty out the reflex of self-importance without shaming us for having one. A person who practices them begins to hear when a sentence is unearned, begins to notice when laughter reveals contempt rather than delight, begins to discern whether a clever phrase conceals a wound. Language calms down. Because quietude has done its work, speech can do its work. It is wise to remember this paradox, that all good conversation emerges from and returns to wordless contemplation.

The Church of the Light, the main chapel of the Ibaraki Kasugaoka Church. Designed by Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

There is also an aesthetic discipline here. In poetry and prose, the pause is part of the line. With maturity, as writers and readers, we learn that what is true off the page is also true on the page. We discover that the strongest passages carry a residue of quietude, as fasting lends flavour to simple food. The mind that returns to this discipline begins to favour verbs over adjectives, begins to trust images to carry weight, begins to leave room for the reader to arrive.

Some passages remain beyond language. Love reaches a splendour there, and art acknowledges its limit. Grief dwells there for a season and needs companions who will sit without diagnosing. Worship bows there by nature, since an excess is present in every rite that refuses capture. The right response is gratitude, and gratitude does not explain. In such territory, words may assist, yet they must behave. The slightest strut breaks the spell.

Of course, to write about silence is to betray it, yet to refuse would be a worse betrayal. Better to circle reverently than to let the unsayable be forgotten. Picard warned that a society hostile to stillness would deform persons. Mallarmé offered a craft that gives words enough air to breathe. The mystics knew that only in quiet can we meet God. The philosophers confessed their limits. What remains is for us to recover what they guarded.

Imagine a choir before the first note. The conductor raises a hand, and a room full of voices becomes one body. There is a living hush, full rather than empty, expectancy without agitation. Then sound pours from that abundance and the ear recognizes a simple law: music honours the quietude that supports it. In the same way, thought and worship and civic friendship borrow their strength from an older stillness. We do not create it; we consent to it.

Consent can be learned. A culture that learns it again will breathe more easily, speak more truthfully, and find itself restored to scale. Silence is the first music, awaiting our consent. To rediscover it is renewal.