A

At first I assumed I misread it. A major private art museum in Potomac, Maryland? The name Glenstone didn’t register, but I knew its location well. This affluent suburb near the edge of Washington, DC, adjacent to the wooded neighbourhoods of my youth in Northern Virginia, belonged to the loose orbit of places that defined the geography of my childhood. On family visits, I’ve witnessed Potomac’s forests and horse pastures give way to gated communities and endless McMansions, its semi-rural landscape slowly transformed by high-end development. I had driven through it for decades and found it hard to picture where a world-class museum might be tucked away. So naturally, as I planned my usual round of DC museum visits during a trip to see family, this new art destination was at the…

A

At first I assumed I misread it. A major private art museum in Potomac, Maryland? The name Glenstone didn’t register, but I knew its location well. This affluent suburb near the edge of Washington, DC, adjacent to the wooded neighbourhoods of my youth in Northern Virginia, belonged to the loose orbit of places that defined the geography of my childhood. On family visits, I’ve witnessed Potomac’s forests and horse pastures give way to gated communities and endless McMansions, its semi-rural landscape slowly transformed by high-end development. I had driven through it for decades and found it hard to picture where a world-class museum might be tucked away. So naturally, as I planned my usual round of DC museum visits during a trip to see family, this new art destination was at the top of my list.

The heat was thick and the air was still as I stepped onto the path leading to Glenstone’s pavilions. The low-slung, minimalist buildings—concrete cubes with reflecting pools linked by glass corridors—emerged gently from a landscape of meadows, restored streams, and woods left largely intact. Inside, cool spacious galleries displayed works by some of the most important artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. From Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain to abstract expressionist paintings by Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline and works of more recent decades from heavyweights like Bruce Nauman and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Glenstone included all the artists one expects to see in any institution of such scale and ambition. Natural light poured in through floor-to-ceiling windows and skylights, joining exterior and interior space. Outside, trails curved through open fields and stands of forest, where outdoor sculptures and installations by artists including Andy Goldsworthy and the artist duo Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller were thoughtfully integrated, appearing like hidden gems. It all recalled the Getty museums back home in Los Angeles, places I love not only for their elegance but for the way they offer a kind of sanctuary. At Glenstone, art didn’t interrupt nature; it moved with it. The whole place invited stillness, as if time itself had been slowed just enough for you to notice it passing.

Glenstone works because it reflects a single, cohesive vision, that of billionaire Mitch Rales and his wife Emily. It’s something public institutions, managed and directed by boards and rotating leadership, often struggle to achieve. Where many museums juggle curatorial agendas and institutional mandates, Glenstone feels unusually focused, almost serene in its clarity of purpose.

The rise of private art museums like Glenstone over the past two decades marks a significant shift in how cultural authority is produced and distributed. Since the early 2000s, more than three hundred private art museums have opened across every inhabited continent, with recent estimates bringing the total to 447 worldwide. Ranging from intimate, appointment-only galleries housed in collectors’ residences to large-scale, professionalized spaces attracting tens of thousands of annual visitors, private museums are praised for their flexibility, aesthetic autonomy, and willingness to take risks. Their founders, directors, and curators typically emphasize how their galleries support younger or more experimental artists or older art that’s been overlooked by traditional institutions often constrained by bureaucratic oversight and pressures to appeal to broad audiences. These spaces showcase the massive personal collections of their founders, often portrayed as cultural stewards who have stepped in where state funding and institutional vision have faltered.

Glenstone. Image by creativecommons/Fuzheado.

But this narrative is complicated by the broader economic landscape in which it unfolds. The expansion of private museums coincides with rising global wealth disparities and an increasing amount of ultra-rich individuals able and willing to convert economic capital into cultural legitimacy. Scholars and critics have warned that these museums, despite their openness, often function as neo-aristocratic monuments, vehicles through which elites inscribe their personal tastes into the public cultural record. Rather than redistributing access to art, they may entrench inequality by outbidding public institutions, shaping artistic canons according to private values, and avoiding democratic oversight—that is, accountability to the public through transparent governance and representation, not private or market interests. The tension is stark: operate with disinterested aesthetic freedom, unconcerned with popularity or ticket sales, are themselves products of an unequal global economy.

American museums like Glenstone, The Broad and the Marciano Art Foundation in Los Angeles, the Rubell Museum in Miami and DC, and the Brant Foundation in Connecticut, and their global counterparts like Foundation Louis Vuitton in Paris, the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, and the Leeum Samsung Museum in Seoul, to name only a few of the most well known, reflect a concentration of cultural power in the hands of billionaire collectors, corporate dynasties, and luxury magnates. Born from vast private fortunes—whether tech, real estate, industry, or family conglomerates—these museums are indicative of the same global economic forces that have widened the gap between the ultra-rich and the public. While they portray themselves as philanthropic gifts to the citizenry, they also serve as expressions of elite identity, influencing the art-historical canon in ways that mirror their founders’ resources and aspirations.

The Art of Patronage

This interweaving of personal influence and public experience isn’t new. It recalls a compelling historical precedent in the widespread inclusion of donor figures in devotional images and altarpieces, a notable convention in Christian art from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance. These images are distinct from standard portraits in both form and function. Rather than being the sole focus of a composition, wealthy patrons had themselves painted into scenes from Scripture in postures of supplication, kneeling beside the Virgin and Child, situated among saints, or as witnesses to important biblical events. These portraits were meant to serve as lasting testaments to the generosity and moral standing of the benefactors who had commissioned the works, and to ensure that their names and deeds would endure beyond their lifetimes.

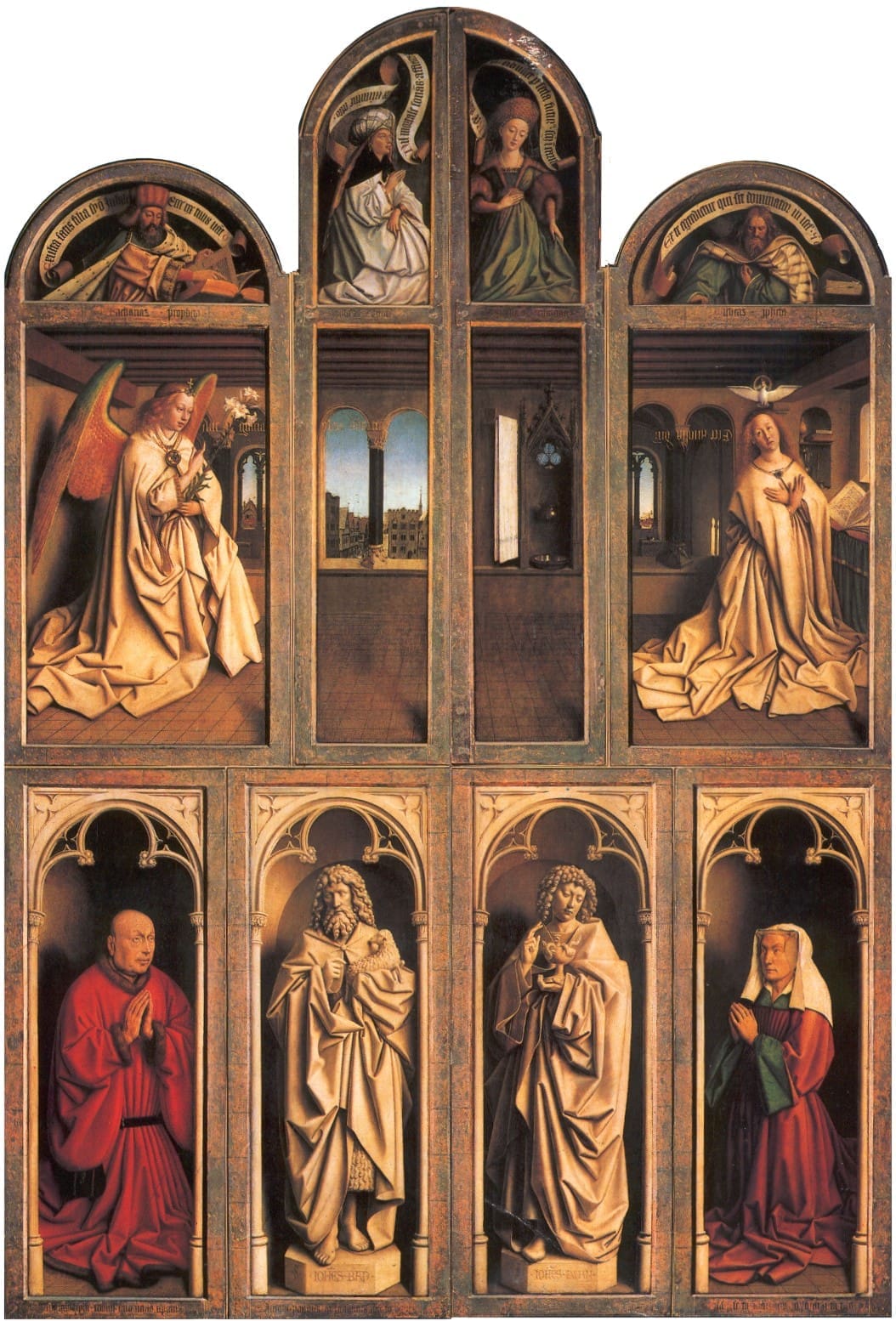

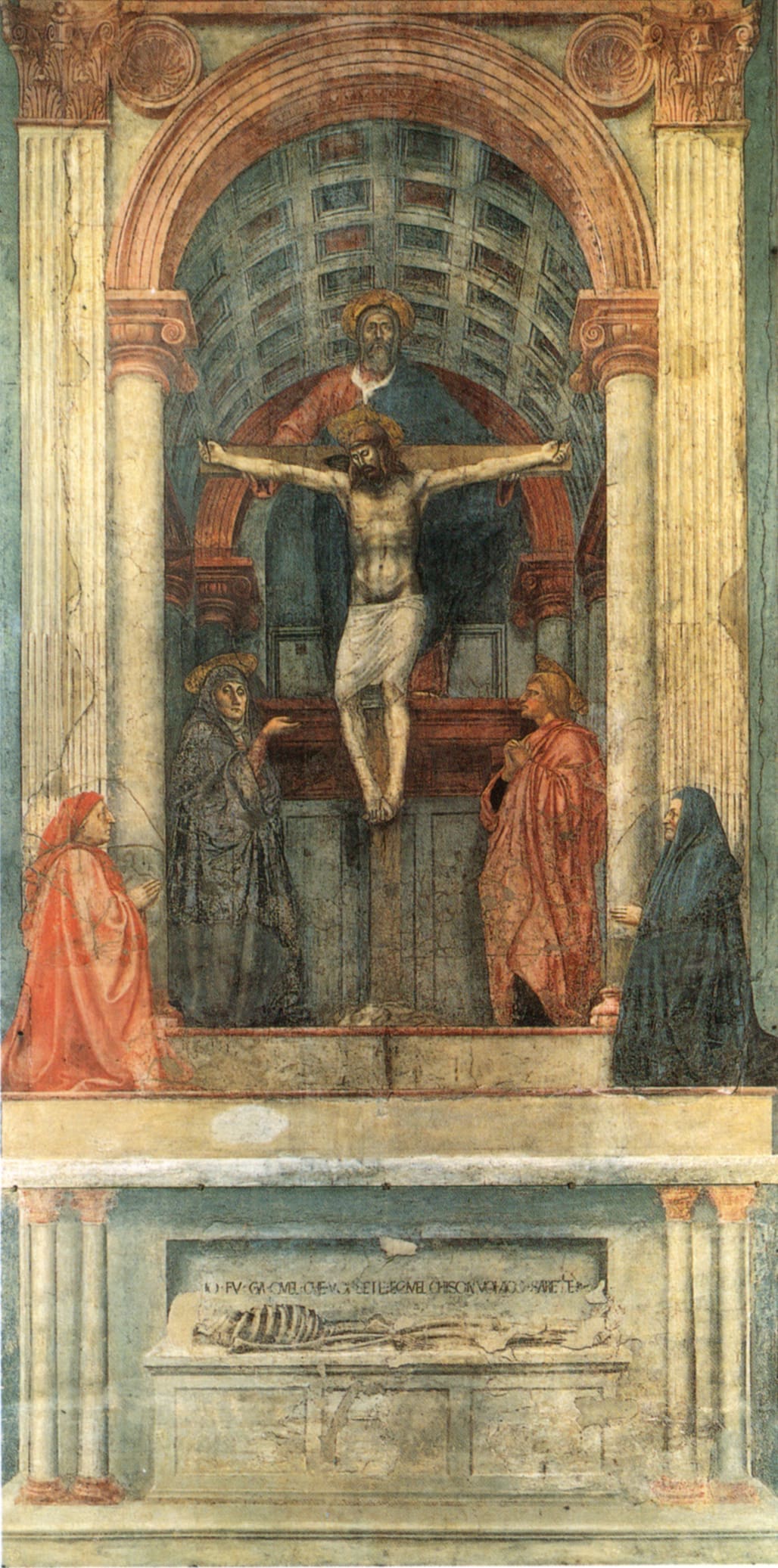

The couples that appear beneath the crucifixion in Masaccio’s Holy Trinity (1427) and on the outside of Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432) are perhaps the most familiar since they are part of renowned paintings. Such figures hover at the threshold of sacred space, not fully within the scene while not entirely outside it either. The donor portrait was meant to promote a patron’s role in the production of the art itself and often the very architecture that housed it. The patron’s hope was that through the prominent display of their piety, future viewers would feel compelled to offer prayers for their souls, or at the very least that the patron might share in the spiritual merit of the prayers directed toward the image. This, they believed, might help speed their journey through purgatory and on to paradise. But these portraits also functioned as subtle frames through which the depicted events were filtered.

For the modern viewer, these earthly figures are strange interlopers. They’re often awkwardly placed or painted at an oddly reduced scale in relation to their surroundings. It’s easy to overlook the presence of the donor at first; I’ve often been caught off guard after realizing that what I assumed was a sacred figure was a contemporary of the artist who had been integrated into the composition. Men, women, entire families—influential in their time but now mostly forgotten—stubbornly intrude into the devotional image. They feel out of place in scenes that depict a reality beyond the earthly—a vision of the world as already and always infused with the presence of God. Indeed, one way to understand these artworks is as visual expressions of the kingdom of God, rendered through gold leaf, halo, iconography, and gesture. They present the true nature of reality through the specificity of sacred narrative or church history. And yet into this vision these ordinary humans inserted themselves—not as saints, martyrs, or angels but as sponsors. In doing so, monarchs, members of royal courts and the nobility, high-ranking clergy, wealthy merchants and widows, guilds and confraternities all left a kind of spiritual footprint: ego layered directly over a space of holiness.

Back panel Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert van Eyck and Jan van Eyck, 1430–1432.

The Holy Trinity by Masaccio, circa 1425–1426.

Although donor portraits had been around since ancient times, they evolved most dramatically from the fourteenth through the sixteenth century. While early medieval depictions often showed donors at a much smaller scale than holy figures, typically kneeling at the margins, by the fourteenth century, and more prominently in the fifteenth century, donors began to be integrated more fully into pictorial space, especially in Early Netherlandish and Florentine painting. They were increasingly shown at the same scale as the main subjects, and though usually remaining peripheral and ignored by the subjects, they sometimes now even interacted with saints.

As portraiture advanced, greater attention was given to individual likenesses, particularly among male patrons, while women were often idealized according to contemporary standards of beauty. Donors began to appear in contemporary dress and were inserted into the action of biblical narratives. Eventually, patrons would appear in major religious roles and populate entire scenes, carrying with them the faint scent of wealth and influence. While the Council of Trent later criticized overly prominent donor imagery and heraldry in sacred art, the tradition continued well into the baroque period and beyond, often in paintings of secular history or in altarpiece formats like triptychs, where donors occupied side panels adjacent to the central subject.

One painting that I have long found haunting and memorable, a particularly compelling example of a Pietà (an image of the Virgin Mary mourning over the dead body of Christ), is the Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon (c. 1455). It exemplifies how these dynamics of patronage and the arts play out in a historically significant work that happens to include a donor portrait.

Enguerrand Quarton’s Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon stands out as one of the most formally rigorous examples of the Pietà theme in fifteenth-century art. Indeed, Quarton’s synthesis of iconographic tradition, personal expression, and compositional harmony marks the painting as one of the most powerful works in Western Christianity. The figures form a balanced arc, with Christ’s body curving gently across the foreground and anchored by the calm verticality of the Virgin at the centre. Unlike more emotionally demonstrative interpretations of the Pietà, Quarton emphasizes restraint: the Virgin clasps her hands in prayer, Mary Magdalene bends forward in quiet grief, and St. John gently lifts Christ’s head, his delicate fingers positioned so precisely that they seem to strum the radiant lines of Christ’s halo, as if playing a celestial instrument.

Pietà de Villeneuve-lès*-Avignon* by Enguerrand Quarton, 1460.

The composition is unified by geometric clarity, seen in the sweeping line of Christ’s body, and echoed in the sharply angled drapery beneath him. A flat gold ground denies deep space and sets the scene outside time, while a distant walled city, possibly a reference to both Jerusalem and Constantinople, offers a subtle historical reference. On the left, the donor, who is a cleric, is found kneeling in prayer. His presence grounds the scene in a specific social context, elevating his status by aligning him with divine authority, so that the painting serves as both instrument of worship and consolidator of power. Clad in a stark white robe that pulls him visually forward, he appears intimately close to the sacred group yet remains emotionally and compositionally detached. His gaze does not meet theirs, and his facial features and body are rendered with the specificity of a unique portrait. He appears as though he’s been pasted in, like a late addition to a finished tableau. Positioned so prominently in the foreground, to us he may seem less like a humble witness and more like someone who’s snapped a selfie in front of a theatrical backdrop. Looked at this way, what better emblem of self-centredness—of the ego’s need to be seen and remembered—could there be?

In a secular age, the ultra-rich channel a similar impulse through their foundations and museums. The unique cultural role of today’s biggest art patrons derives not just from how they impact the art market or validate and consecrate particular artists. Through architecture, programming, and public image, the museum extends the vision of its founder, not only in terms of what’s deemed worthy of attention, but also in the very frameworks through which we are taught to look. Unlike public museums, which tend to speak in many voices, private institutions speak through the worldview of a single collector and, on occasion, their family. These are monuments to private kingdoms, not of stone and sovereignty, but of cultural capital fuelled by riches and motivated by the enduring desire to leave a mark on the world.

The Centre of Reality

The beauty in altarpieces and panel paintings makes God’s nearness visible. The greatest works of painters like Cimabue, Giotto, Fra Angelico, and Memling offer more than iconography; they draw us into an aesthetic experience that exceeds the image itself, awakening a felt sense of presence that is larger than the self. Here, sacred art offers us a guide for today’s visual culture: it reveals that all great art, of any subject or for any purpose, can open us to this same transcendent ground. Not by depicting God directly, but by creating space for an encounter with the real. Art commissioned by the church in centuries past can help us better understand why we feel moved by the power of contemporary art. Even when the light is dimmer, the source may be the same. Beauty, fundamental to art, is, as the great mystic Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite has said, a name for God.

Yet even as art draws us toward the mystery of reality, traces of something else remain. In the gleam of a donor’s robe or the prominence of a name carved in stone, we glimpse other forces at work. Personal kingdoms shaped by legacy and status. These human-made kingdoms have always existed alongside the sacred, competing for our attention with the non-material reality that art makes perceptible.

Christians writers as different as Dallas Willard, Richard Rohr, and N.T. Wright all describe, in helpful ways, the tension between the small kingdoms we build—rooted in control, ego, and self-interest—and the expansive, boundless kingdom of God. In The Divine Conspiracy, Willard quotes John Calvin’s sharp line: “Everyone flatters himself and carries a kingdom in his breast.” Willard describes that internal realm as the place we rule from—the little empire we protect and grow. The divine kingdom is “the range of God’s effective will,” not a far-off destination, but wherever God’s purposes are enacted, including within the human heart. In one of his homilies, Rohr calls these our “little kingdoms,” built from ego and defended by belief and identity. The kingdom of God is “a state of consciousness,” a transformation that occurs when we step beyond the confines of the ego and live in loving union. Wright speaks of “personal and political kingdoms” that make it hard to perceive God’s reign at all. The true kingdom is not about escaping this world but about God’s rule being enacted “on earth as in heaven,” starting with the renewal of hearts and communities. Wright makes clear that the kingdom of God is not a possession or project. It breaks in—softly but persistently—and begins its work in and through us, remaking the world.

When we look at devotional images through this lens, we see more than religious iconography. We begin to sense a rendering of that divine reality that Christians call the kingdom of God. These aren’t just pictures of the sacred; they provide conditions in which we might feel it. The most vital devotional art holds doctrine and presence together; its formal language and iconography express theological truth even as they invite us into divine encounter. In that sense, doctrine becomes embodied, felt through colour, form, and gesture, rather than merely stated. That’s what art can do: not just inform but transform. Not just show us something but shift something in us. And that’s true even with contemporary art that no longer names God. If it still calls us beyond ourselves, still awakens the ache for beauty, still opens us to presence, then it too functions sacredly. It too discloses aspects of the real by engaging viewers through its own form of beauty. Contemporary art, like much of what’s found at places like Glenstone, frequently refuses to settle into a single meaning. This allows mystery to surface, reflecting the elusive, expansive nature of reality itself. In both religious and secular forms, art gestures toward the real by drawing viewers beyond themselves—through embodied meaning, evocative presence, or both—inviting encounter, reflection, and a fuller sense of being.

There’s also this: no matter how effective the framing, the art we encounter in any institution, whether public or private, has the capacity to slip beyond the limits placed on it. Great art in all times is unruly. It doesn’t comply with boundaries. Whether encountered in pigment or glass, bronze or video, it has a way of spilling over the interpretations we apply to it. Sometimes it unsettles. Sometimes it surprises. At its best, it produces in us feelings of awe and wonder.

The kingdom of God isn’t built on legacy or good taste, and its visualization isn’t limited to one style or era. It opens outward. It invites us beyond our self-made categories into the fullness of reality as it participates in God’s life. And art awakens us to the beauty, givenness, and communion at the heart of creation—allowing us, however dimly, to perceive the divine ground of being. Whether it’s framed in gold or shown in a white cube, whether made for the church or for the wider world, one of art’s most powerful qualities is that it can slip past the defences we didn’t know we’d built.

So when a donor kneels humbly at the edge of a Pietà, or a collector’s name crowns a museum wall, what we’re seeing isn’t just pride or legacy but a metaphor for the ways we all try to place ourselves at the centre of things. A reminder of how often we project mental concepts onto the canvas of reality, and how easily we mistake our private kingdoms for the real thing. And yet, through all of it, the art still beckons—past the ego, past the frame, toward the beauty that always leads beyond the known.