LISTS Field Notes: A Beginner’s Guide to Soundwalks By Matthew Blackwell · Illustration by [Maria Contreras](https://daily.bandcamp.com/contributors/Maria Contreras) · October 23, 2025

In 1966, the musician and artist Max Neuhaus met with some friends on the corner of Avenue D and West 14th Street in Manhattan. He stamped the word “LISTEN” on their hands and led them toward the East River. Without a word, the group went past a humming power plant, across a rumbling highway, over a windy pedestrian bridge, and back through the busy Lower East Side. As a percussionist, Neuhaus worked with composers like [John Cage,](https://cageedition.bandcamp.com/…

LISTS Field Notes: A Beginner’s Guide to Soundwalks By Matthew Blackwell · Illustration by [Maria Contreras](https://daily.bandcamp.com/contributors/Maria Contreras) · October 23, 2025

In 1966, the musician and artist Max Neuhaus met with some friends on the corner of Avenue D and West 14th Street in Manhattan. He stamped the word “LISTEN” on their hands and led them toward the East River. Without a word, the group went past a humming power plant, across a rumbling highway, over a windy pedestrian bridge, and back through the busy Lower East Side. As a percussionist, Neuhaus worked with composers like John Cage, who integrated sounds from the outside world into their pieces, but he suspected that the audience was more intrigued by the shock of the unexpected than they were willing to consider the sounds on their own merit. Neuhaus repeated his walk for the general public in a series of “Lecture Demonstrations,” explaining that “the rubber stamp was the lecture and the walk the demonstration.” These walks were a way to open the ears of participants, to give aesthetic validity to a world that was sometimes noisy, chaotic, and overwhelming.

Neuhaus didn’t know it yet, but he was one of the first leaders of a soundwalk. In the 1960s, performance artists were questioning the constraints of institutions and increasingly taking their work to the streets, blurring the boundaries between art and experience. His “Listen” series evolved from a tradition of conceptual art in which scores were written to be performed by anyone at any time. Take, for example, these instructions from Yoko Ono’s 1962 Map Piece: “Draw an imaginary map. Put a goal mark on the map where you want to go. Go walking on an actual street according to your map.” Or Milan Knižak’s Walking Event, from 1965: “On a busy city avenue, draw a circle about 3m in diameter with chalk on the sidewalk. Walk around the circle as long as possible without stopping.” By adding the simple command to listen, Neuhaus transformed his participants into both performers and audience members at once, directing their attention to the sonic environment of their everyday lives.

The term “soundwalk” was not formalized until later, with the World Soundscape Project at Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, R. Murray Schafer, Barry Truax, and Hildegard Westerkamp began studying noise pollution in their city, leading to the 1973 publication of the book and record set The Vancouver Soundscape*. *A key part of their research was the soundwalk, which Westerkamp defined as “any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment.” She goes on to instruct her readers how to become listeners: “Wherever we go we will give our ears priority. They have been neglected by us for a long time and, as a result, we have done little to develop an acoustic environment of good quality.”

Soundwalking exists at the intersection of art, field recording, urban studies, and acoustic ecology. Perhaps the most important reference point, however, is Pauline Oliveros’s practice of Deep Listening. Oliveros’s 1974 text Native succinctly describes the ideal state of a sound walker: “Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears.” This focus on mindfulness has attracted an increasing number of people to the discipline. A soundwalk is a chance to take our eyes off our screens and our headphones off our ears, a tantalizing opportunity in an increasingly distracted world.

Viv Corringham, a vocalist and sound artist who has been practicing soundwalks for 25 years, says that “soundwalks allow our busy eyes to take a break and relax their gaze; this encourages a different focus of attention, allowing everyday sounds of the place to resonate within us.” Since she began her own practice of soundwalking, Corringham has observed how the field has evolved as it has gained popularity. “The basics remain the same but new approaches have arisen, often rooted in environmental concerns or in ‘decolonial’ listening that questions dominant Western understandings of sound.” A soundwalk is fundamentally inclusive, yet also political: Anyone can participate, but the nature of that participation is determined by factors such as location, gender, disability, and many others.

This means that you, too, can start soundwalking, right now. “Just go outside and listen. Remember that you are part of the soundscape too,” Corringham advises. “Notice whether you can hear the sounds of your own presence. Through our walking feet, we can listen to the song of the journey, to traces of previous walkers, to stories from the earth, to echoes of ancient origins, and to our own memories and associations. The essence of a place is revealed to the feet that move through it and listen.”

Soundwalking is an embodied practice, historically experienced firsthand; if a specific walk were to be shared, it was usually through written instructions, maps, or in-person events. However, artists have increasingly incorporated recording into their soundwalking practice, finding exciting ways to share their own experiences through sound. Below is a selection of recordings that demonstrates the many directions that a soundwalk can take.

**Hildegard Westerkamp

Montreal, Québec

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

Montreal, Québec

Hildegard Westerkamp is perhaps the foremost expert on soundwalks, having defined the term in her 1974 essay “Soundwalking” and continuing to practice today. Her album *Transformations *features a key piece, 1989’s “Kits Beach Soundwalk,” in which she narrates her walk across Vancouver’s Kitsilano Beach. She describes the small sounds of waves washing over barnacles as she goes, cleverly using the recording medium to replicate the shifts of attention that occur during a soundwalk. “Suddenly, the background sound of the city seems louder again,” she says, as she raises the volume. “It interferes with my listening. It occupies all acoustic space, and I can’t hear the barnacles in all their tininess.” Other tracks on *Transformations *come from field recordings of Vancouver’s Skid Row, Vancouver Island’s old-growth rainforest, and the Mexican desert. Although they may not strictly be called soundwalks, they all derive from Westerkamp’s careful listening and keen sense of sonic space.

**Terry Fox

Germany

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

Germany

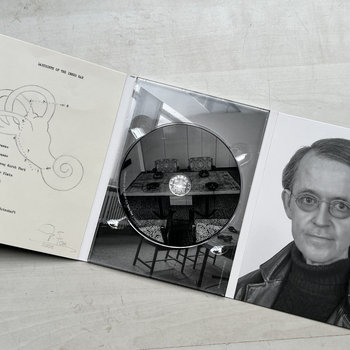

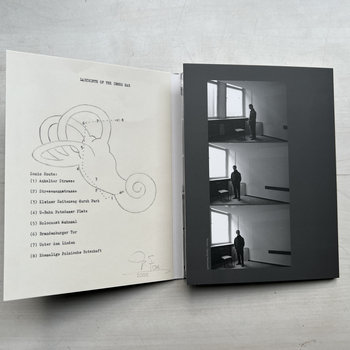

*Labyrinth of the Inner Ear *is a guided tour of Berlin given by a blind man, the artist Siegfried Saerberg, accompanied by Terry Fox and Ernst Karel. The trio walked through the city for two days leading up to the 2006 Sonambiente Festival; Saerberg wore binaural microphones while Karel carried a boom mic, and the recordings were then mixed by Karel and pressed to CD according to Fox’s conceptualization. The piece works because, as listeners, we are guided through Berlin’s busy streets via Saerberg’s ears, dependent on his tapping and sweeping cane to determine the type of environment he is navigating. From quiet side streets, into the U-Bahn, through the Holocaust memorial, and past groups of tourists, we are led through the city’s labyrinth and finally back to his starting point. *Labyrinth of the Inner Ear *showcases the ability of the soundwalk to cross disciplines—disability studies, urban planning, sound art—and make another person’s experience come vividly to life.

**Craig Shepard

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

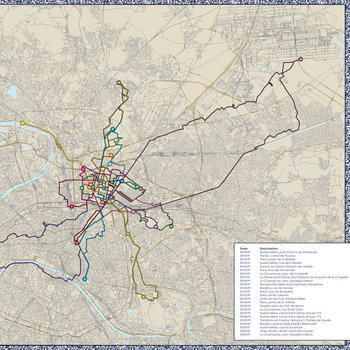

Wandelweiser composer Craig Shepard has always enjoyed walking, but he began soundwalking in earnest when one of his European tours was canceled. “I still wanted to do a tour, so I reduced it to the minimum: I bought a tent, a pocket trumpet, and maps of Switzerland. Each day I walked, composed a piece, and performed it outdoors. That was my first On Foot project,” he says. “For me, it began as a practical way to do an ultra-low-cost tour. As I continued, I noticed that my mind worked differently. My attention was broader and sharper. Something like meditation.” Since that first On Foot album from 2005, Shepard has repeated the process in groups, leading silent walks in Brooklyn and in Aubervilliers, France. “When a group walks in silence, there is a bubble which moves with the group through a space,” he explains. “In a sense, the group creates the silence. Generally, it’s easier to do what those around one are doing; I’ve noticed I listen more acutely with others.” His Aubervilliers project illustrates the point: the group stopped at the midpoint of each walk, where “each participant’s stillness became their performance,” and it is easy to imagine yourself among them with these excellent recordings.

**Chris Watson

Edinburgh, UK

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

Edinburgh, UK

During the coronavirus lockdowns, walking became an important way to connect with the outside world. At the same time, the world got quieter, making the sounds of wildlife more noticeable to many. In March of 2020, premier field recordist Chris Watson was asked by artist Alec Finlay to record soundwalks for Scottish charity Paths for All, which would be “aimed at people, not just with regards to the pandemic, but who are less able physically to get out,” Watson explained. “Alec’s idea was to take people to these places in sound. So I did binaural mixes because really, that’s designed for headphone listening. You can just put the headphones on, close your eyes, and go to that place. There’s a narrative element to it. It’s a journey.” Watson made two mixes, one of the Scottish Highlands and one of the Lowlands, that offer “imaginative access” to these astonishing environments. Though the lockdowns are over, these recordings remain essential.

**Andrew Weathers

**AW Walks in Two Different Commerce Spaces

Pueblo, Colorado

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

Pueblo, Colorado

Andrew Weathers’s *AW Walks *series explores the nature of places as they are revealed through walking, and how we can either open ourselves up to them or close ourselves off. After AW Walks to the West Bank of the French Broad Every Day and AW Walks Two Memories in the Bay Area, Weathers walked in Two Different Commerce Spaces: an open market in Valparaíso, Chile, and a dead mall in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The juxtaposition of these two atmospheres reveals what is distinct in each: the market is vibrant, lively, and invigorating, while the mall is slow, reverberant, and eerily quiet (the fountain is often the loudest part). These are the types of places that slip into the background of everyday life, and that soundwalks encourage us to re-encounter with new ears. And, though Weathers insists that they are not “intended as some kind of critique of consumer culture,” these recordings prompt us to consider where we spend our time and money, and how those choices impact the built environment.

**Kate Carr

London, UK

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

London, UK

Field recordist and Flaming Pines head Kate Carr got up early on June 21, 2023, the summer solstice, to travel east along the Thames. *Midsummer, London *tracks her progress through wittily descriptive titles: for example, “A strangely located cafe, echoes of St Paul’s and a drain that drew breath as I journeyed into Blackfriars” and “Crossing the river: I am getting hungry and lots of people are talking about food. Also, Jesus loves me.” It took Carr all day, but she has condensed the journey into about 45 minutes of strange encounters accentuated by eerie drones and effects. The result is not an objective portrait of London, but an effective example of the city’s psychogeography on the longest day of the year—surreal and slightly mad.

**Angus Carlyle

Santa Fe, New Mexico

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Angus Carlyle was in the Norwegian section of the Sápmi region, north of the Arctic Circle, when he heard a passing mention of the “electrical sounds of the countryside.” He writes of his resolve to capture these sounds: “Although tempted to spend the next morning staring at the grey-blue sea and listening to Röyksopp’s Profound Mysteries Vol. 1–3, I determined to head out into the sleet and slush and after a trudge through knee-deep snow that had been softened by rain, I found an electricity pole in the woods near a small stream.” We join Carlyle as he struggles through the snow, recording the buzzing of the electrical poles along with wind, sleet, and the conversation of passing Norwegians. *Powerlines *is less a walk than a trek, with all of his effort, frustration, and eventual triumph evident in its unfolding narrative.

**Viv Corringham

London, UK

...

.

00:10 / 00:58

London, UK

Viv Corringham volunteered for London’s Resonance FM radio station in 1998, where she was introduced to the work of Hildegard Westerkamp and Barry Truax. As a vocalist, she saw an opportunity to combine singing with soundwalking. Though some soundwalking practices encourage silence, Corringham emphasizes the interaction between the listener and their environment. “In my own artistic practice, it is a way to combine listening, vocal response, and place,” she explains. “Walking and singing are both embodied activities—moving through an environment while responding vocally to what is heard, remembered and imagined.” Both volumes of Corringham’s *Soundwalkscapes *series see her reacting in real time to what she encounters. She sings and hums, she mimics wildlife, and she revives bits of history by describing lost rivers underneath London or lost African American communities in New York City, the ideal leader of your own personal soundwalk.