Digital Logic

Fabs and EDA companies collaborate to provide the abstraction of synchronous digital logic to hardware designers. A hardware design comprises:

A set of state elements (e.g., registers and on-chip memories), which retain values from one clock cycle to another

A transfer function, which maps the values of all state elements at clock cycle N to new values of all state elements at clock cycle

N+1

The transfer function cannot be too fancy. It can be large but cannot be defined with unbounded loops/recursion. The pragmatic reason for this restriction is that the function is implemented with physical gates on a chip,...

Digital Logic

Fabs and EDA companies collaborate to provide the abstraction of synchronous digital logic to hardware designers. A hardware design comprises:

A set of state elements (e.g., registers and on-chip memories), which retain values from one clock cycle to another

A transfer function, which maps the values of all state elements at clock cycle N to new values of all state elements at clock cycle

N+1

The transfer function cannot be too fancy. It can be large but cannot be defined with unbounded loops/recursion. The pragmatic reason for this restriction is that the function is implemented with physical gates on a chip, and each gate can only do one useful thing per clock cycle. You cannot loop the output of a circuit element back to itself without delaying the value by at least one clock cycle (via a state element). It feels to me like there is a deeper reason why this restriction must exist.

Many people dabbled with synchronous digital logic in college. If you did, you probably designed a processor, which provides the stored program computer abstraction to software developers.

Stored-Program Computer

And here comes the inception: you can think of a computer program as a transfer function. In this twisted mindset, the stored program computer abstraction enables software engineers to define transfer functions. For example, the following pseudo-assembly program:

0: add r1, r2, r3 // r1 = r2 + r3 1: blt 0, r1, r4 // branch to instruction 0 if r1 < r4 2: sub r1, r1, r2 // r1 = r1 - r2 ...Can be thought of as the following transfer function:

switch(pc) case 0: r1 = r2 + r3; pc = 1; break; case 1: pc = (r1 < r4) ? 0 : 2; break; case 2: r1 = r1 - r2; pc = 3; break; ...In the stored program computer abstraction, state elements are the architectural registers plus the contents of memory.

As with synchronous digital logic, there are limits on what the transfer function can do. The switch statement can have many cases, but the body of each case block is defined by one instruction. Alternatively, you can define the transfer function at the basic block level (one case per basic block, many instructions inside of each case).

Programming in assembly is a pain, so higher level languages were developed to make us less crazy.

C

And here we go again, someone could write an interpreter for C. A user of this interpreter works at the C level of abstraction. Following along with our previous pattern, a C program comprises:

A set of state elements (variables, both global and local)

A transfer function

For example, the following C function:

int foo(int x, int y) { int result; result = x + y; // statement 0 if (result < 0) result = -result; // statement 1 return result; // statement 2 }Can be thought of with as the following transfer function:

switch (statement) case 0: result = x + y; statement = 1; break; case 1: result = (result < 0) ? -result : result; statement = 2; break; case 2: return_value = result; statement = pop_return_statement(); break;Think of return_value and pop_return_statement as intrinsics used to implement function calls.

The key building blocks of the transfer function are statements. It is easy to just store the term “statement” into your brain without thinking of where the term comes from. A statement is a thing which can alter state.

This transformation of an imperative program into a transfer function seems strange, but some PL folks do it all the time. In particular, the transfer function view is how small step operational semantics are defined.

Python

And of course this can keep going. One could write a Python interpreter in C, which allows development at a higher level of abstraction. But even at that level of abstraction, programs are defined in terms of state elements (variables) and a transfer function (statements).

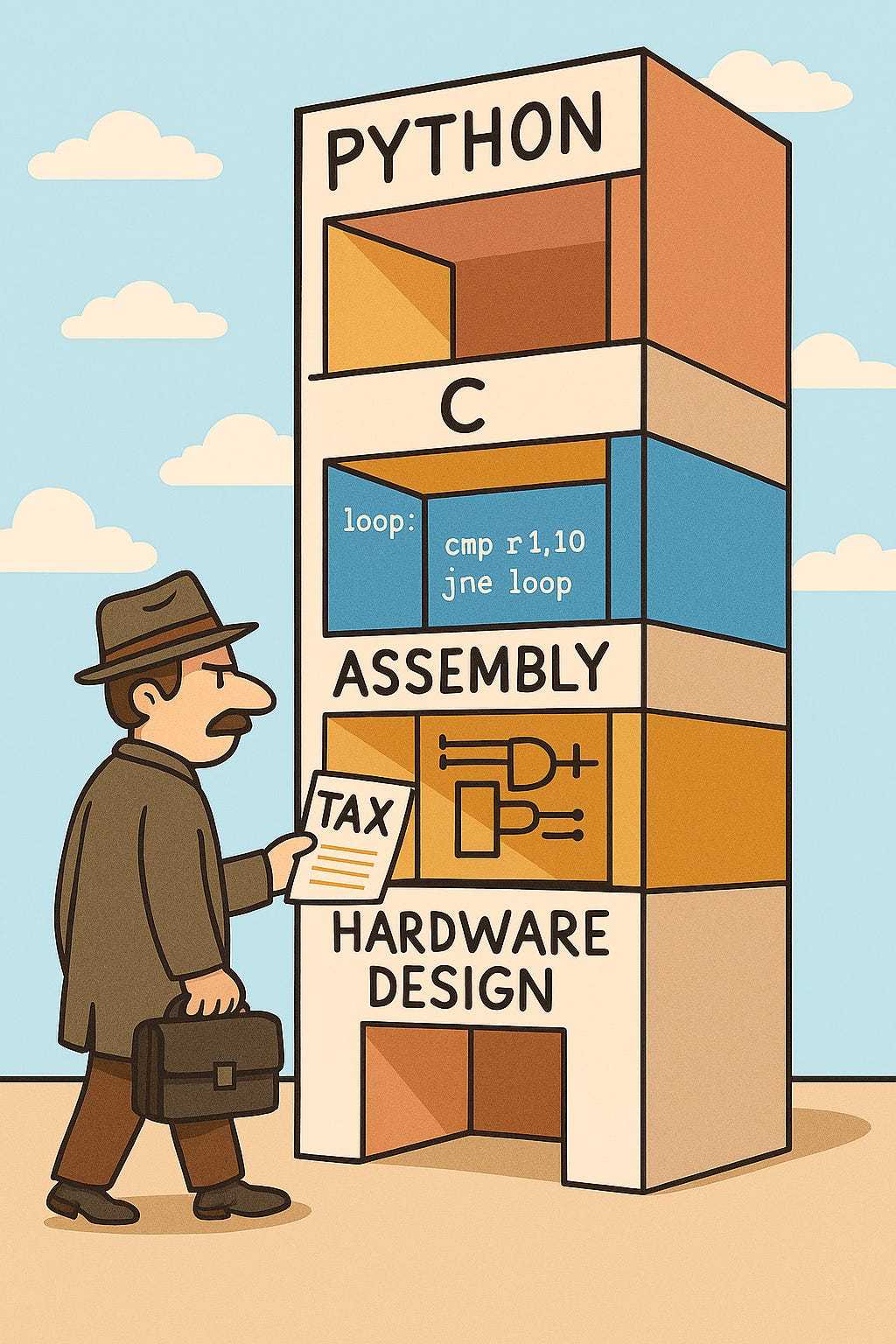

Turing Tax

The term Turing Tax was originally meant to describe the performance loss associated with working at the stored-program computer level of abstraction instead of the synchronous digital logic level of abstraction. This idea can be generalized.

Code vs Data

At a particular level of abstraction, code defines the transfer function while data is held in the state elements. A particular set of bits can simultaneously be described as code at one level of abstraction, while defined as data at a lower level. This code/data duality is intimately related to the Turing Tax. The Turing Tax collector is constantly looking for bags of bits which can be interpreted as either code or data, and he collects his tax each time he finds such a situation.

An analogous circumstance arises in hardware design. Some signals can be viewed as either part of the data path or the control path, depending on what level of abstraction one is viewing the hardware from.

Compilers vs Interpreters

A compiler is one trick to avoid the Turing Tax by translating code (i.e., a transfer function) from a higher level of abstraction to a lower level. We all felt awkward when I wrote “interpreter for C” earlier, and now we can feel better about it. JIT compilers for Python are one way to avoid the Turing Tax. Another example is an HLS compiler which avoids the Turing Tax between the stored-program computer abstraction layer and the synchronous digital logic layer.

Step Counting (Multiple Taxation)

No, this section isn’t about your Fitbit. Let’s call each evaluation of a transfer function a step. These steps occur at each level of abstraction. Let’s define the ultimate performance goal that we care about to be the number of steps required to execute a computation at the synchronous digital logic level of abstraction.

The trouble with these layers of abstraction is that typically a step at a higher layer of abstraction requires multiple steps at a lower layer. For example, the multi-cycle processor implementation you learned about in a Patterson and Hennessy textbook could require 5 clock cycles to execute each instruction (instruction fetch, register fetch, execute, memory, register write back). Interpreters have the same behavior: one Python statement may be implemented with many C statements.

Now imagine the following house of cards:

A Python interpreter which requires an average of 4 C statements to implement 1 Python statement

A C compiler which requires an average of 3 machine instructions to implement 1 C statement

A processor which requires an average of 5 clock cycles to execute 1 machine instruction

When the Turing property tax assessor sees this house, they tax each level of the house. In this system, an average Python statement requires (4 x 3 x 5) 60 clock cycles!

Much engineering work goes into avoiding this problem (pipelined and superscalar processors, multi-threading, JIT compilation, SIMD).

Partial Evaluation

Partial evaluation is another way to avoid the Turing Tax. Partial evaluation transforms data into code.

Dangling Pointers

There must be some other method of creating abstractions which is more efficient. Self-modifying code is rarely used in the real world (outside of JIT compilers). Self-modifying code seems crazy to reason about but potentially could offer large performance gains. Partial evaluation is also rarely used but has a large potential.