- 11 Nov, 2025 *

A couple of days ago, Eurogamer’s main English branch published its two-star review of ARC Raiders, a piece where freelancer Rick Lane dinged the game hard for its embrace of AI-generated voice acting. It’s a score that stands in stark contrast not only to the rest of the site’s extended linguistic family, but also its immediate peers across the rest of the games media landscape. As of this writing, virtually every other outlet of a similar level of prestige and prominence has given the game an equivalent score of 85/100 or above, with the overall mean sitting well in the 90s. It’s the most minor of chink…

- 11 Nov, 2025 *

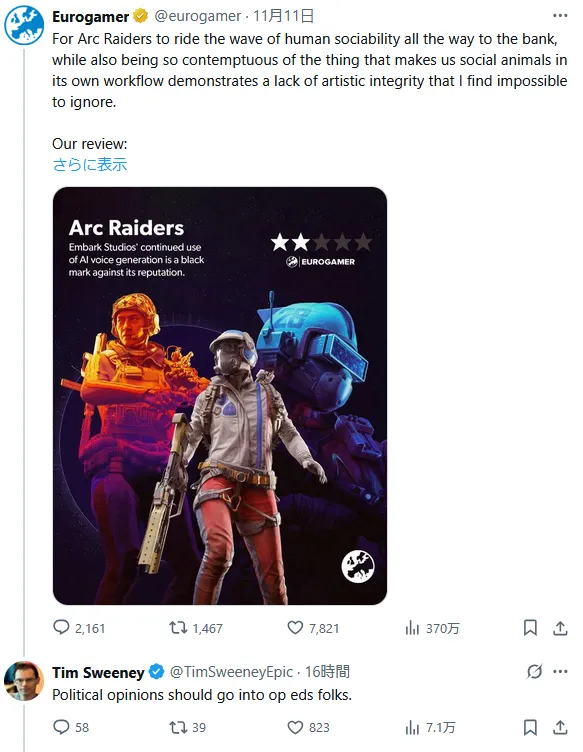

A couple of days ago, Eurogamer’s main English branch published its two-star review of ARC Raiders, a piece where freelancer Rick Lane dinged the game hard for its embrace of AI-generated voice acting. It’s a score that stands in stark contrast not only to the rest of the site’s extended linguistic family, but also its immediate peers across the rest of the games media landscape. As of this writing, virtually every other outlet of a similar level of prestige and prominence has given the game an equivalent score of 85/100 or above, with the overall mean sitting well in the 90s. It’s the most minor of chinks in the game’s critical armor, yet has apparently proven so threatening to some profiteers accustomed to a pliant tech press that one Tim Sweeney, billionaire head of no less than Epic Games, disingenuously slogged it for being a thought piece with too much editorial. This, despite his own company sitting comfortably above the Metacritic fracas these days as only the humble maker of Fortnite, its Unreal Engine arguably responsible for many of its own clients’ review struggles this decade. It’s an exercise that’s all too familiar to anyone who was there for the infamous GameSpot 8.8/10 in 2006, a number that remains singularly recognizable to readers of a certain age, as well as countless other instances of members of the games press declining to take part in what players and developers alike insist is a moment of coronation for the talk of the town that day, not of introspection.

During a perilous moment in time for media organizations of all stripes, it is, on the one hand, a heartening moment. A fleeting moment for most of us except, perhaps, the writer himself, but a heartening one nonetheless. But as a fellow freelancer working on the other end of the equation, specifically as a localizer, it’s in many ways a bittersweet moment above all else. While one minute Eurogamer and other outlets like it may appear willing to take AI and its proponents to task for its ethically and legally dubious foundation and especially its impacts on the labor it’s actively displacing, particularly through layoffs that commonly number in the tens of thousands, the next, it’ll turn to machine translation to report on foreign news, especially developments not already covered in English by specialist outlets.

Perhaps you’ve read Brian Merchant’s piece on the existential danger that AI poses to many of my peers across most every field in translation. I would call it sobering had I not already been living in that reality for the entirety of my professional career, so allow me to reframe the fight against AI through the lens that I’ve seen it develop on the ground. Before AI was the latest capital-I It in tech finance in a string of failures to goose up growth numbers, before AI was even on the tip of anybody’s tongues outside of laboratories and academia, to people like me, it was machine translators in the wake of DeepL. While other sites had already long abandoned a naive 1:1 view of translation embodied by the likes of old Internet stalwarts like Babelfish, the selling point of DeepL and its progeny was that it was designed to output far more naturalistic-looking text than had been common until that point. To laymen, its fluency alone gave it an air of legitimacy and competency over its competitors. The secret sauce lied in statistics. Namely, an array of real world material was fed into DeepL’s machine learning algorithms, which the site then used to probabilistically connect the dots in determining what a word in one language most likely meant in another.

The system was otherwise never built to have rhyme nor reason like a real translator must exercise on a daily basis. Any semblance of those things simply came down to it possessing enough back-end reference material to guess the translation’s expected cadence within a given context. If it failed to parse the source text, it was perfectly capable of completely manufacturing baseless translations, the telltale blatant inaccuracies and stilted phraseology symptomatic of past solutions now papered over with smooth prose. These attempts to cover-up such hallucinations, as some might correctly be inclined to call them, were only to be expected, a consequence of the systems examining material written to professional standards. If anything, it would’ve been more shocking had it not attempted to impersonate the acumen of real translators doing their jobs not only correctly, but well; perhaps even enjoyably. It was therefore technology designed to impress monolingual people and especially monolingual people who pay for translation as a service, not the people who render the service itself.

Since then—and I must stress, well, well before AI become the buzzword du jour of boardrooms across the globe—translation agencies, which are companies that serve as middlemen between translators and their actual clients, have largely won in using machine translators to fundamentally alter the nature of the job. At the biggest such outfits, completely human driven-translators are portrayed as a luxury, even if the rates they pay out reflect that narrative less with each passing year. Instead, the name of the game now is PMTE, or post-machine translation editing, a process where the source material is first run through a machine translator and then inspected by a human. At a minimum, intervention is expected in cases of outright factual errors, but it’s also not uncommon for clients to emphasize the E in PMTE and request editing that leads to a punchier final product.

Agencies argue that, by virtue of putting the onus of the first draft on the machine translator (ie: allegedly the bulk of the work), PMTE is inherently faster and more efficient at producing deliverable content than human translations. As a result, PMTE jobs are offered with lower rates, the expectation ostensibly being that any per-job drop in income can be made up by simply doing more PMTE. Less time taken for one assignment means more time to take on, you guessed it, more assignments. In practice, this tends to not be the case. Quite often, PMTE ends up being a far more time and labor-intensive methodology due to the added step of comparing an existing translation against the original text, rather than immediately drafting a translation from scratch and moving on at a steady pace. Nevertheless, because PMTE isn’t priced to reflect the actual effort required to achieve a satisfactory end result, it’s had the knock-on effect of depressing rates for full human translations despite their supposed luxury status, as the latter must now compete against false narratives of the alternative’s superior efficiency. These diminishing returns are taking place across virtually all subject matters, not just entertainment like my own. Even legal, patent, and medical translators, people whose manual input was deemed most vital to maintain for decades as a matter of liability, integrity, and trustworthiness, are under as much duress, if not more so due to unfair perceptions of formulaic, repeatable compositional standards in their work.

If these refrains sound familiar because of complaints from creatives in other sectors—the appropriation, the hallucinations, the assertions of enhanced productivity, the downward pressure on income—it’s not a coincidence. Translators have been the canary in this particular automated coal mine longer than most everyone else. Businesses have successfully and profitably rendered us unnecessary in so many use cases that the tactics and rhetoric that have been battle-tested against us under various guises for decades are now being deployed verbatim against everyone else AI has set its sights on. What may feel like a new menace to my fellow writers and especially my artist, musician, and voice actor friends is sadly anything but to people in my business. Translation was always, to a certain type of technologist and investor, an obvious, intuitive test case to explore the possibilities of machine learning and hone its applications. It’s only after their thinking was proven fiscally correct that, now that AI “proper” is capable of imitating the work of far more occupations, those fangs are bared at them, as well.

Which brings us back to Eurogamer and its ilk. In writing all of this, I’m not ignorant of the struggles that the games press in a sea of layoffs, diminishing SEO in an era of AI search, and evaporating ad revenue for coverage of anything but chart toppers and Amazon sales. If any writers or editors working for such outlets end up reading this, I’m sure their first instinct will be to argue that the money simply isn’t there to hire more than the few people they already have. That they would like to bring on people like me for their international coverage, but that news is news. It needs to be reported in the interest of their readership one way or another, whether it’s by citing the work of regional specialists or, indeed, turning to machine translators that they reckon are reliable enough, so long as they nominally include the caveat that their choice of words came from a computer.

It’s an argument, however, that reflects only international news as it functions today from such publications, not how it once did for years. Many of the writers left working today may be too young to remember for themselves, but in the heyday of print magazines and early Internet outlets, it was standard practice to employ bilingual experts when reporting on other countries, most typically Japan. Peruse the archives of GameSpot and IGN from the turn of the millennium and you’ll quickly find game previews and business news out of events like Tokyo Game Show written not with machine translators or niche competitors as a crutch, such as they even existed, but by handlers who understood the local landscape and could navigate it in ways the main editorial staff could not. Together with a concerted focus on import game reviews where relevant, niche as they always were, it was an ecosystem that allowed individuals with language skills to contribute to the vital, all-encompassing coverage of such sites. Not only that, the direct, consistent access to such knowledge made for better informed journalists and editors within those institutions in a number of ways, even with the limitations of a pre-social media Internet. Western games media lost an incalculable amount of in-house insight in the budgetary switch from translators as trusted, valued peers to translators as purely an outsourced commodity.

But at the end of the day, retaining translators even when pressed for cash isn’t, shouldn’t, and cannot be merely a matter of best practices to be followed in better times and healthier economic climates. It’s simply the professionally responsible thing to do. Places like CNN, Al Jazeera, and countless other generalist news organizations don’t turn to machine translators when they have news to share from other parts of the world and it’s because any respectable reporter appreciates the added stakes that come with bridging language barriers while maintaining factuality. By the very nature of the work entailed, translation and interpretation will always involve literally putting words in people’s mouths. When a subject doesn’t speak English or any other target language, careful decisions have to be made on their behalf not only about what they say, but the semantics and rhetorical devices behind it. With an audience that includes politicians, businesspeople, voters, and other decision-makers, their image is on the line, as is that of the publication choosing to share their words with a global audience. Few first impressions matter more and are more consequential than ones made through translation and interpretation because the person represented in most cases can’t set the record straight themselves if it isn’t set right the first time.

Replacing human translators with machine ones doesn’t remove that subjectivity from the equation and make the ensuing translation any more objective or credible. Human translators may come to different, discretionary conclusions with respect to their approaches, but machine translators never show their work, the logic employed in coming to their conclusions infinitely more opaque. They cannot do their own homework, cannot self-select based on localized contexts, cannot draw upon their own lived experiences in both languages and cultures to navigate any unspoken or unwritten murkiness; they only have the existing back catalog of material provided for A:B comparisons and a (human) programmer-defined model dictating correctness solely by likelihood.

You cannot ask a machine translator additional questions about why it chose the words that it did, why those exact words are suitable for the situation, and why they’re best at conveying those ideas and opinions to a foreign audience. You only get their final verdict, take it or leave it. And to take it rather than leaving it is like taking Phil Spencer at his word that all is well at Tango Gameworks after the release of Hi-Fi Rush. Like letting Kenneth Lay claim that Enron’s growth was as prodigious as its ledgers professed. Like allowing Donald Trump to insist that his own tariffs “haven’t led to inflation. We [the United States] have no inflation,” as he did on 60 Minutes just days ago. If you believe due diligence is necessary before telling any side of a story, then it shouldn’t be a stretch for translations to be held to a similar, necessarily high standard of veracity. And you can’t get that veracity from a machine that goes silent as soon as its work is done.

In our current environment, steady, sustainable, honest jobs for honest translators without the pressure of feeding an industrial monster today so that it might better eat its survivors tomorrow are fewer than ever. A decade of work that, in better times, would’ve long earned me a senior position within a developer’s internal ranks has seen me lose longtime agencies, more project managers pushing me turn to my translation skills to proofreading wholly unqualified newcomers for less money, and a loss of six figures’ worth of income, all within a matter of 18 months. Couple that with other ongoing endemic issues within localization and the wider industry, including highly inconsistent crediting and a lack of royalties on even the most critically acclaimed, multimillion-selling games, works that I have sometimes personally led for years on end, and I am left treading water, stuck in a financial place that resembles the place where I began far too close for comfort. There was even a time when members of the English games press would occasionally reach out and hire me to assist on their Japan dispatches, whether it was to assist with back-and-forths, facilitate interviews, or do research into topics with predominantly Japanese sources.

But no more. Now, all of that is long gone, quite possibly for good. Any promises of future work remain fleeting, some offers tentatively at best months out, others by even years. Clocks are ticking on me, my deadline to renew my work visa in Japan, and my ability to continue performing the job I’ve trained and studied for my entire adult life. Try as I well and truly might, I honestly cannot tell you in good faith whether I’ll still be here doing this in a year’s time. Kind words, as generous as they’ve often been, turn into paychecks with rarer frequency, often to the tune of months. And every time I see a news post in solidarity with the equally noble struggles of other working class developers to put food on their tables, mine feels invisible the minute those same places write four exhausting words: “according to machine translation.”

#ai [#machine translation](https://dateemups.com/blog/?q=machine translation) #personal