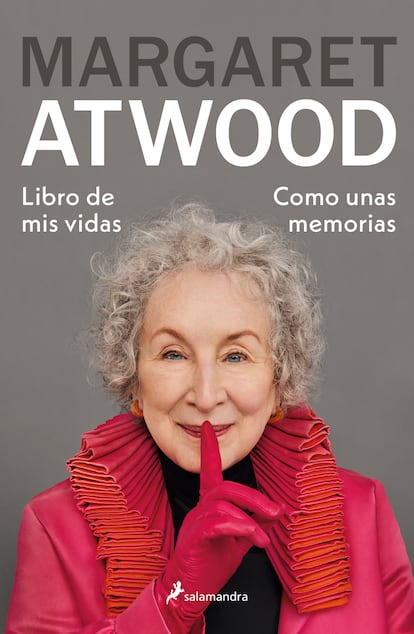

It’s rush hour at this busy downtown Toronto café, but no one seems to notice Margaret Atwood, Canada’s most famous writer and one of the most celebrated in the world. Petite, dressed in dark clothing and wearing a hat that hides her white, curly hair, 85-year-old Atwood moves through the café unnoticed and, on one of those sunny days when the Canadian autumn timidly bares its winter teeth, chooses the terrace to speak in a low voice, with her customary irony, about her highly anticipated memoirs.

She didn’t see the point in writing them (“Who wants to read the story of someone sitting at a desk wrestling with a blank page?” she asks in the book; “It’s boring enough to die of boredom,” she concludes), but she finally did. And she has titled her memoir The Book of Lives, because tha…

It’s rush hour at this busy downtown Toronto café, but no one seems to notice Margaret Atwood, Canada’s most famous writer and one of the most celebrated in the world. Petite, dressed in dark clothing and wearing a hat that hides her white, curly hair, 85-year-old Atwood moves through the café unnoticed and, on one of those sunny days when the Canadian autumn timidly bares its winter teeth, chooses the terrace to speak in a low voice, with her customary irony, about her highly anticipated memoirs.

She didn’t see the point in writing them (“Who wants to read the story of someone sitting at a desk wrestling with a blank page?” she asks in the book; “It’s boring enough to die of boredom,” she concludes), but she finally did. And she has titled her memoir The Book of Lives, because that is exactly what it is: a far from boring, generous, and good-humored account of the lives fate handed to someone always ready to downplay herself — from a wild childhood to a wandering youth; from her awakening as the poet recently awarded the Joan Margarit International Poetry Prize to her rise as a celebrated novelist; and from her maturity as the prophetic author of The Handmaid’s Tale to the years of widowhood after the death in 2019 of her second husband, Graeme Gibson, her lifelong partner and father of her daughter.

The book, more than 600 pages long, is also the story of a lost era: the story of the postwar generation and the evolution of social customs in the second half of the 20th century, the triumphs and tribulations of feminism, and the emergence of Canadian literature, which, thanks to her and her contemporaries, rose in the shadow of hegemonic United States. On that topic, it’s said that Atwood — “Peggy, to friends,” she clarifies — is its grande dame.

Question. In the book you reflect on fame, but, given what we’ve seen, it doesn’t seem to be such a big problem.

Answer. It’s because one of my editors kept saying, “but were you famous then? But were you famous then?”

Q. When did you become famous?

A. It depends on the definition we choose… This is Canada. People here are pretty intent on what they’re doing. I get recognized a lot at airports. That’s where I fall into what I call “the selfie ambush.”

Q. After reading the book, one would say that you have had a good life.

A. It was luck. It was a lucky time in history to be here. A lot of your life is time and place.

Q. The book at times reads like a kind of The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig...

A. The world of the day before yesterday, in any case [Laughter]. I’m one of the few people alive who remembers those years.

Q. You write about a time when “there wasn’t enough of anything.” Now there’s more or less too much of everything. Do you miss those years?

A. I think we always miss years in which we were younger than we are.

Q. Are you nostalgic?

**A. **Not at all. We think of when we were younger as having been superior. But they weren’t necessarily. The 20s and 30s are a hellhole.

Q. Why does your book spend 400 pages to your first 40 years and 200 to the second 40?

A. Because things get less interesting when you get older!

Q. Are there any pleasures in growing older?

A. That you don’t have to worry too much about the future. You already know where it leads! That gives you more freedom to say what you think, although I’ve always had that freedom. I have been a self-supporting writer since 1971.

Q. Given that there is too much of everything… are you optimistic about the future of humanity?

A. Challenging times are ahead for several reasons: the demographic time bomb, environmental degradation, the great ice melt, and global warming (which is not good news for Spain). Also, the possibility that someone will get trigger-happy with the atomic bomb and actually push the button.

Q. You remember when that almost happened…

A. During the Cuban Missile Crisis [in 1962], I was studying Victorian literature at Harvard. We thought we were going to be blown up while discussing Tennyson’s poetry.

**Q. **In the book, you go from one house to the next. Have you counted how many you’ve lived in?

A. No. I’ve had this one since 1985. We bought it from a cult. Before that, we lived in one that they said had a phantom…

Q. Did you see it?

A. No. Apparently, it was a woman in a blue dress whose story involved the loss of a baby. We tried to trace it in the archives, but we couldn’t find anything. When we were young, there weren’t enough of us to fill the needs of the baby boom. So it was quite easy to get a job. That’s why children of the Great Depression were so lucky. Then came the baby boom. I’m pre-hippie…

Q. But you tried LSD.

A. Yes, I found it boring.

Q. And what about ayahuasca? In the book, you mention that a friend recently invited you to try it…

A. No, even though he suggested quite strenuously. Vomiting isn’t my thing.

Q. At the beginning of your memoir, you argue that every writer leads a double life.

**A. **Every writer has a double life, one who lives and the one who writes, including you.

Q. Correspondents in the United States only have the one Trump allows us.

**A. **I’ll give you a very bizarre thought. Considering our ages, I could have been his babysitter. I would have been 13 when he was seven.

Q. Perhaps you could have contributed to making the world a better place.

A. Surely, it would have been enough to share some instructive stories with him...

Q. Is writing a memoir a way of having the last word?

A. You never have the last word. You should know that by now. Or don’t you read the letters to the editor?

Q. I was thinking of the Canadian writer Alice Munro and the scandal — which you recall in your book, and which broke after Munro’s death — when it became known that her husband was a pedophile who had assaulted her daughter, and that she looked the other way. Do you think that if Munro had written her autobiography, she would have managed to justify herself?

A. She couldn’t. She was diagnosed with dementia much earlier than people think, maybe in 2005. Nobody knew until it became very obvious. So after Gerry [Fremlin, her husband] died, we realized she’d been covering it up. By the time she received the Nobel Prize [in 2013], she didn’t even know who she was anymore.

**Q. **Have you given up on the idea of winning the Nobel Prize?

A. I never had it. I suppose I was too controversial a candidate, and then I got too old: 80 is probably the limit to win it.

Q. Does it bother you that this award is presented as something that supposed favorites lose every year?

A. You cannot lose a literary prize. Prizes are for those who give them, rather than those who receive them.

Q. It’s been 40 years since you published The Handmaid’s Tale, and in Trump’s Washington, protesters are dressing up as characters from Gilead, the dystopian and oppressive world for women that you imagined…

A. When we premiered the film in the eastern part of Berlin shortly after the fall of the Wall, people told us, “This was our life.” Surveillance is what defines totalitarian regimes. And those weapons of population control have improved tremendously in the last 40 years. Can that happen in the United States? I don’t think so, and I’m tempted to add “yet.” Trump and his people aren’t that well organized. And again, I hesitate to add “yet.”

Q. In your memoirs, you make it clear that you didn’t seek inspiration for The Handmaid’s Tale beyond the Iron Curtain, but in the United States…

**A. **That’s right: in 17th-century puritanism. All the dictatorships we know have a supreme leader. Why doesn’t Gilead? Because it’s a society ruled by religion and the church…

Q. There are people in Washington who want to revive those ideals on which the United States was founded — ideals they say should continue to guide the nation’s destiny.

A. Christian nationalism is a contradiction in terms. Christianity is supposed to be a universal religion. It’s worse when you add the adjective “white.” A large proportion of Christians live in Africa.

Q. How do you see the resurgence of traditional values promoted by figures like the murdered MAGA activist Charlie Kirk and defended by his young followers? The traditional family, the superiority of the West, the idea that procreation is a woman’s destiny...

A. Christianity was actually emancipating to women in the beginning, and a lot of its early supporters were women. I hope Christian nationalists remember the reason the Founding Fathers separated church and state, a separation they now want to undo. They knew what the factional wars within Christianity had wrought in the Europe they fled.

Q. In the book, you define a middle ground between dystopia and utopia — “Ustopia.” It may be my professional bias, but from the United States it’s hard not to read that as U.S.-topia, an American utopia. You describe it as “a period of chaos that has allowed a strong administration capable of taking charge to seize power.” Were you thinking of Trump?

A. Of course, he would like to achieve that. He is working tirelessly to get rid of democratic foundations such as the separation of powers. And many people are complying in advance. It reminds me of those show trials in the 1940s in the USSR, where the accused didn’t even know what they were accused of and yet pleaded guilty.

Q. Did you like the ending of the series The Handmaid’s Tale?

A. Let’s just say I haven’t had time to look at it yet. I don’t really want to say anything about it.

Q. Was it always clear that you wouldn’t have control over where the story would go?

A. No production company would give a writer veto power. They’d be crazy to do that. I signed a contract in the 1980s that included the television rights, but back then nobody believed a book like this would ever become a series. It took streaming, and the possibility of telling stories longer than 100 minutes. They started making things up on their own from the second season onward. They did follow a rule I impose on myself when I write: never include anything in the plot that hasn’t happened at some point in human history.

**Q. **Speaking of things that hadn’t happened before, how have you experienced Trump’s attacks on Canada? Did they awaken a dormant nationalism in you?

A. No. I’ve been through this before. In the late 1960s and 1980s, when we fought against being so dependent on the United States. In the 1960s, we wanted to establish basic cultural institutions; they didn’t exist. When a publisher told me I needed an agent, I had no idea what that was… Now the rejection of Trump is stronger, but fundamentally, the relationship is the same. We’re separated by one of those one-way mirrors: we can see them, but they can’t see us.

Q. Do you boycott U.S. products?

A. We’ve all started reading the labels, but I wouldn’t call it a boycott, but rather making informed decisions.

**Q. **Canadian author Louise Penny decided not to promote her book in the United States. Will you do the same?

A. I’ll only go to two cities, but that’s because I’m too old to embark on one of those tours I used to go on. Canadians have many friends and relatives down there, but they’ve stopped traveling to the United States. People are afraid of being stopped at the border.

**Q. **Do you agree with those on the right who celebrate the death of “wokeness”?

A. I think it’s pretty much dead, yes. If we’re talking about automatic cancel culture on social media, it happens less; people got fed up. For someone from my generation, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights generation, it was never a good idea to do like the Queen of Hearts from Alice in Wonderland, have a verdict first and trial afterwards. If you study the history of witchcraft, it’s the same. First they were judged, and then they had to prove they weren’t witches.

Q. You’ve said that people have always thought of you as a bit of a witch… Does that still happen now that you’re a venerable legend of world literature?

A. Now I’m the Good Witch from The Wizard of Oz. Older women are only allowed to be two things: wise old women or wicked old witches. Sometimes, both at once…

Q. In your memoirs, you tell anecdotes — like that of a suitor who harassed you — that would be read very differently today. Do you believe in looking at the past through the eyes of the present?

A. We can’t help it. What we can’t do is see the past with the eyes of someone much younger than you. You can listen to what they have to say, but you’re not necessarily going to intuitively know what such a person would think any more than they can intuitively know what you’re going to think.

**Q. **Like that feminist who was called a “bad feminist” for defending Stephen Galloway, the Canadian professor accused of sexual harassment… Would you say the movement is particularly divided now? I’m thinking of the disputes over trans rights...

A. All movements throughout history have had internal power struggles, from Christianity to the Bolsheviks. Feminism is no different. It has had its ups and downs ever since the French Revolution chose the slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” … and not sorority [laughs].

Q. At what point did people stop thinking of you as a writer for women?

A. When I started, novels weren’t published in Canada; it was too expensive, so poetry was the main vehicle of expression. More than men or women, we were Canadian writers. We created a publishing network, and the novel took center stage. Then came the second wave of feminism, and that’s when the differences began. I had to tell newspaper editors not to send me only books by women, and there were men who didn’t want to review books by women for fear of being considered misogynistic. In the 1980s, we experienced a pushback from the feminism of the 1970s. The 1990s were a time of anarchy, and feminism was a no-word in publishing. In the 21st century, the third and fourth waves arrived. Right now, I don’t think it’s a good time for feminist writers because people got turned off the #MeToo movement. It’s the same old story: the pendulum of history. The sweet spot is in the middle, but also the hardest to defend: you’re attacked from both sides.

Q. You never wanted to turn your husband’s death into literature. Suffering from dementia, he died of pneumonia in a London hotel room while you were there promoting your latest novel, The Testaments. Those circumstances could have provided a valuable contribution to the literature of grief... Was it hard to write about that in your memoirs?

A. No, because it wasn’t the first time. I wrote the new introduction to his bedside book of birds, and I wrote a pamphlet about going birding together for a foundation we set up. My memoir is also about that, about the many things in life that you have no choice but to accept.

Q. Do you go birding without him?

**A. **Oh yes. We’re currently building a center at a place called Pele Island. We gather there every spring to witness the bird migration.

Q. Do you consider yourself more of a novelist than a poet, or just a writer?

A. I wouldn’t say just. I would say also. If I preferred one or the other, I would only do that one.

Q. Are you planning to write a new novel?

A. I’ll never tell you that. I don’t show anybody anything until it’s done.

Q. At the end of Book of Lives, you don’t seem very worried about the idea of dying.

A. Do I have a choice?

**Q. **None of us do, but some seem to fear it more than others…

A. Death frightens people your age. A German artist did a photo project in cemeteries and interviewed writers about death. He told me that young people had no objection to this. Neither did the older ones. It was the ones in between who didn’t want to do it. I’m not thrilled about the prospect, but I’ve come to terms with it.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition