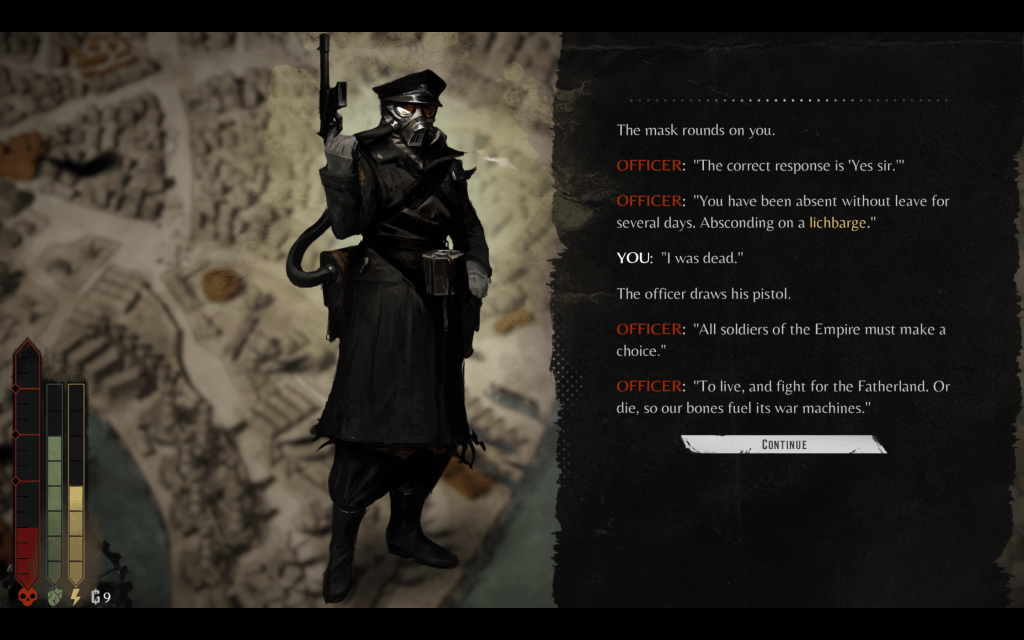

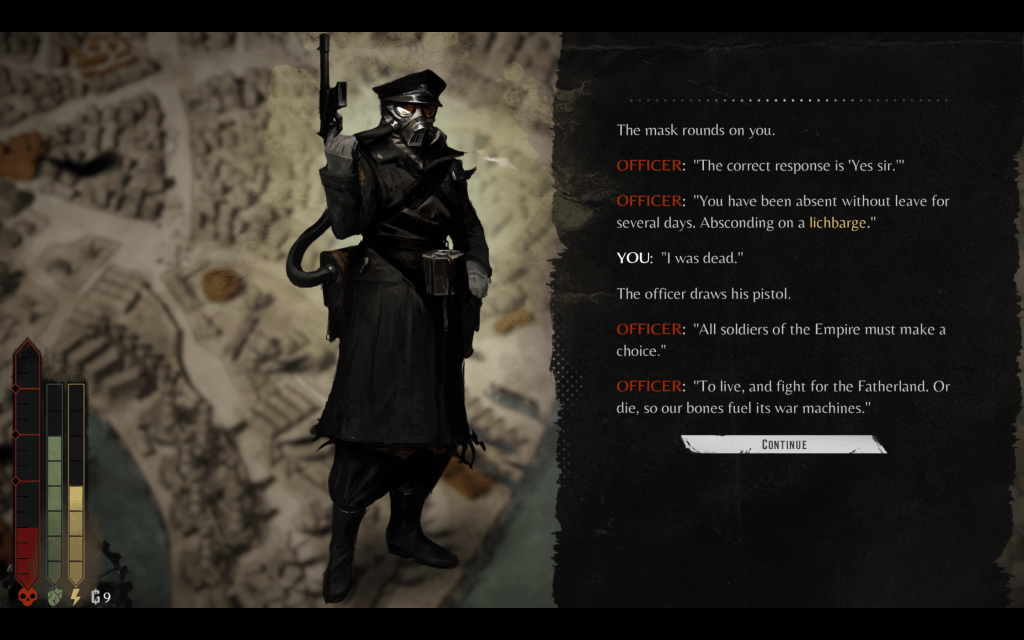

I don’t want to fuel the war machines. Source: Author

The kindness found in the city of Dredgeport can be summed up by what my customi…

I don’t want to fuel the war machines. Source: Author

The kindness found in the city of Dredgeport can be summed up by what my customized character Dread saw at the Hydale Poor House. After peeking into its windows, observing struggling people sew clothing and eat gray soup, he watched two orderlies drag a corpse from the Poor House and toss it in the back of a cart. That cart was on course for the plasmyards, the place where all the dead go to keep the city alive as their corpses are turned into the too-valuable resource called plasm, or lichoil. As the game puts it at the end of this scene, the Hydale Poor House “is not a place of kindness. It’s a place to store raw human material, until they are ready to be harvested.” The corpse being shipped away made it hard to argue with this claim, and after spending a few more hours in Dredgeport, I must extend that sentiment to much of the poor city.

This city is the setting of Duskpunk, a RPG that takes major cues from the Citizen Sleeper games when it comes to dice-rolling mechanics, multiple character presets, text-heavy presentation, and themes of revolting against the opportunistic powers that be, but manifests a unique experience in its steampunk aesthetic, war-focused story, and method of exploring said themes. Whereas Citizen Sleeper examines agency and inequality through its Sleepers, whose bodies are owned, abused, and hunted by mega-corporations, Duskpunk investigates similar themes through the lens of a left-for-dead soldier, who is owned, abused, and hunted by the ruler Little Father’s Empire.

My time with Duskpunk’s demo was depressing — not because it wasn’t fun, but instead for its interpretation of a city stricken by war times. The city of Dredgeport is a place stewing with death, paranoia, and opportunists of all types that you can befriend or antagonize. It is a place to survive first, thrive in if you’re lucky later. Even the friendly service given to Dread by the priest Brother Rejchek, who found Dread crawling in the alleyway he slept in, must be questioned. Kindness feels more like a mask than a face in these parts, to the point where it was easier to trust the beggar who stole 3 groats, Dredgeport’s currency, from Dread than it was the priest who gave me shelter and urgent medical attention.

Alleyways don’t exactly make for sound sleep. Source: Author

Alleyways don’t exactly make for sound sleep. Source: Author

Dredgeport is a city where a soldier is considered lucky if they arrive dead, for at least then they wouldn’t be plagued by memories and nightmares that actively increase a Stress meter. The fuller this meter gets, the more negatively impacted your dice rolls and skills are. The war memories aren’t the only stressors — as there are plenty of other opportunities for a bad dice roll — but the memories are what Dread carries into bed every night, and the quality of his sleep is a weighted factor in Duskpunk’s experience. What makes things even more distressing is the method of relief: a drug called Solace that helped Dread at the war front, but is known to be less effective with each use. The bullet on top of this status quo is recruiters who are looking for him once they realize he didn’t die like a good soldier is expected to, forcing him to not just survive in Dredgeport but also figure out how to avoid the draft that promises Hell.

Dredgeport is not without some warmth. Outside of Brother Rejcheck, the engineer Zai who is willing to give me a metal prosthetic for my freshly sawed off foot, and other characters I ran into, question marks dot the map that reveal small glimpses into daily life. This has included a metal forger who makes steel impressions of passerby, much like a caricature artist would do on the streets of New York City, as well as a chapel that offered a kind of peace that only silence from the city’s marching boots and wary souls can offer. However, even these moments are undercut by the other scenes found at these question marks, such as the public chaining of two women accused of being Orrayan agents for stealing rations. Seeing scenes like this make it a lot easier to buy into the revolutionary talk being hushed throughout the streets, but where that talk could lead is a mystery for the full game.

However, I doubt I’ll need to learn much more to join any cause dedicated to overthrowing the regime running Dredgeport. War is an all-consuming monster that ruins lives on and off the battlefield — any society fueled by the corpses spat out by that monster will see little praise from me. The implications of Dredgeport’s particular makeup are horrifying to ponder: what is the incentive for a society to stop a war that keeps the lights on? What lies and half-truths must be compounded so that the thirst for blood constantly outweighs the hunger forming in countless stomachs? How many ideas have been choked in infancy, forced underground, or blasted out of existence for fear that it may stop one more person from being turned into a resource? And even if there is a revolution against the Empire, will it mean more or less bloodshed for an already exhausted populace?

These questions likely won’t have easy answers, if answers at all, but I know they will haunt me until I dive deeper into the depths of Dredgeport. Duskpunk launches on November 19, and with it the large swaths of Dredgeport kept behind clouds on the city map. I’m ready for what the rest of this city holds. I dread the discoveries that will test that statement.

Thanks for reading this article. If you enjoy Exalclaw’s work, subscribe below so the next post comes directly to you for free! And consider leaving a tip to support the site’s work: https://ko-fi.com/exalclaw.