1748-9326/20/11/114081

Abstract

Collective progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal (LTTG) remains insufficient, a shortfall to be addressed by new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The Agreement stipulates that countries’ NDCs will represent a progression and reflect their highest possible ambition (HPA). However, the vague conceptualisation of this HPA norm challenges its translation into practice, allowing states to reference ambition in their NDC without clear evidence. Recently, the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) advisory opinion on climate change provided clarification regarding this norm. The level of ambition communicated in an NDC is not entirely left to the discretion of states but must constitute an adequate con…

1748-9326/20/11/114081

Abstract

Collective progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal (LTTG) remains insufficient, a shortfall to be addressed by new Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The Agreement stipulates that countries’ NDCs will represent a progression and reflect their highest possible ambition (HPA). However, the vague conceptualisation of this HPA norm challenges its translation into practice, allowing states to reference ambition in their NDC without clear evidence. Recently, the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) advisory opinion on climate change provided clarification regarding this norm. The level of ambition communicated in an NDC is not entirely left to the discretion of states but must constitute an adequate contribution to the collective achievement of the global temperature goal. States are obliged to exercise due diligence to ensure their NDCs reflect their best efforts. Building on the ICJ’s interpretative guidance, we propose a structured framework to operationalise the HPA norm and reflect upon considerations of ambition in countries’ NDCs. The framework’s core pillars incorporate domestic, international, and implementation considerations in NDCs, elaborated upon in two elements per pillar. Under domestic considerations, NDCs should be based on a faithful assessment of mitigation options utilising national capabilities. International considerations require contributions that adequately support the LTTG while balancing equity. Implementation considerations demand that NDCs account for the co-impact of the measures considered and be actionable in the near term to ensure ambition is translated into action. The Paris Agreement-HPA Framework can support transparent communication of the conditions under which more ambitious targets can be pursued. We apply the framework to explore the engagement of current NDCs with the framework’s elements. Finally, the framework empowers societal stakeholders to interrogate, verify and, when necessary, challenge whether NDC preparations were carried out with due diligence, supporting accountability in global and national climate action.

Export citation and abstractBibTeXRIS

Countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) remain collectively insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal (LTTG) of holding global warming well below 2 °C and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, as outlined in Article 2.1(a) of the Agreement (Rogelj et al 2023, 2024, UNFCCC 2024a, 2024b). While Article 4.3 of the Paris Agreement stipulates that each Party’s successive NDC shall represent a ‘progression’ beyond the previous one and reflect its ‘highest possible ambition’ (HPA), neither the treaty nor the Paris rulebook define what HPA means (UNFCCC 2015, 2019, 2022). In practice, formulating NDCs of HPA has largely been left to the discretion of states (Preston 2021). Although the HPA norm has been conceptualised as a ‘regime-specific marker’ of due diligence obligations to the Paris Agreement (Voigt and Ferreira 2016, Malaihollo 2021, Patt et al 2023, p 23, Voigt 2023, Mayer 2024, Rajamani 2024), its operational parameters remain vague, presenting challenges to its translation into measurable, reportable, and verifiable actions.

The recent advisory opinion on climate change by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) clarified the legal obligations of states in relation to climate change, including what a reflection of HPA in NDCs involves (ICJ 2025)4. In relation to Article 4.3, the ICJ states that the level of ambition communicated in a Party’s NDC is not purely discretionary to the Party (ICJ 2025, para. 242). Interpreted in light of the object and purpose of the Paris Agreement and the customary obligation to prevent significant harm to the environment (ICJ 2025, para. 242), it establishes that a Party’s HPA must be capable of making an adequate contribution to the collective achievement of holding global warming to below 1.5 °C5.

The obligation to prevent significant environmental harm applies directly to the climate system and states’ legal responsibilities under international climate change law (ICJ 2025, paras 134, 273), informing the context in which the Paris Agreement operates. To fulfil their duty to prevent harm to the climate system, states are expected to exercise due diligence (ICJ 2025, paras 135, 245, 280), a behavioural standard in international law. The due diligence standard refers to an obligation of conduct and requires states to ‘deploy adequate means, to exercise best possible efforts, to do the utmost’ (ITLOS 2011, paras 11, 24). Echoing the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the ICJ reiterated that the due diligence standard to prevent significant harm is particularly stringent in the climate change context (ICJ 2025, para. 138). This stringent standard also applies to NDC preparation. Every Party ‘must do its utmost to ensure its NDC reflects the HPA’ to reach the Paris Agreement’s LTTG (ICJ 2025, para. 246). The adequacy of an NDC is to be assessed with reference to whether a Party exercised due diligence and deployed appropriate measures (ICJ 2025, para. 252).

Significantly, the ICJ has articulated several elements of conduct to determine due diligence obligations in the climate context (ICJ 2025, para. 136). While their applicability and relevance contextually vary, these elements may individually or in combination support the formulation of the applicable standard in specific cases (ICJ 2025, para. 280). As the HPA norm’s meaning is shaped by the duty to prevent significant environmental harm and Parties are expected to exercise due diligence to ensure NDCs appropriately contribute to the Paris Agreement’s objectives (ICJ 2025, para. 245), these elements yield guidance to understand what HPA in NDCs should involve in practical terms.

While the ICJ offers welcome clarification on the scope of the HPA norm, its legal interpretation comes without structural guidance on how to operationalise the norm in a policy context.

We address this gap by developing a framework to assess the ambition of countries’ NDCs, building on the ICJ’s clarifications. This work offers a practical understanding of the HPA norm, supporting countries in pursuing NDCs of HPA that are both nationally owned and context dependent. Equally, it enables societal stakeholders to examine, and when necessary, challenge whether the NDC was prepared with due diligence. We first outline the context and possible interpretations of HPA, then introduce the framework, discuss its practical implementation, and apply it to the first two NDC rounds.

2.1. The ordinary meaning of a progression in HPA

The ordinary meanings of the terms HPA and progression provide a foundational understanding of the framework. Ambition, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as a ‘strong desire for achievement’, reflects motivations, incentivises action, and yields a forward-looking perspective (OED 2024, Duvic-Paoli et al 2023). The highest degree of effort helps countries conceptualise the expected stringency their NDCs ought to pursue (Voigt 2016). Recognising the possibility of these efforts acknowledges that proposed actions need to be achievable, the different circumstances in which ambitions are set, and that these circumstances impact a state’s capability to pursue specific efforts. Thus, the ordinary meaning of the HPA norm suggests that NDCs need to show a strong desire for achievement (of the Paris Agreement goals) while accounting for equitable contributions that represent countries’ possibilities.

The HPA norm operates alongside the concept of progression, creating a dual obligation (Voigt 2023) and promoting a ‘direction of travel’ (Mayer 2021). Progression, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as the advancement towards a goal (OED 2024), has been described as setting the ‘floor’ of ambition (Duvic-Paoli 2023). It forms a minimum expectation that prevents backsliding in countries’ efforts. As every progression equates to an increase in ambition (Rehbinder 2022), the progression requirement in isolation can be interpreted as being met by any increase in ambition (Bodansky et al 2017). However, considering the Paris Agreement’s notion its implementation should be effective (UNFCCC 2015, Art. 3), the interrelation of the progression requirement with the highest effort mandates ambition to be a proactive step towards meeting the LTTG (Doelle 2016). Every successive NDC should reflect a country’s best effort, creating the expectation that Parties continuously re-evaluate their contributions within the scope of their possibilities given national circumstances.

2.2. The ICJ’s clarification on the HPA norm

The ICJ’s advisory opinion on climate change informs the operational understanding of the HPA norm. The court’s interpretation of Article 4.3 of the Paris Agreement provides authoritative guidance on Parties’ obligations of conduct in the formulation and communication of their NDCs. The ICJ clarified that the level of mitigation ambition in NDCs is not entirely left to countries’ discretion (ICJ 2025, para. 242). The HPA norm must be read considering the context, object, and purpose of the Paris Agreement (see section 2.2.1 below), and the customary obligation to prevent significant environmental harm (ICJ 2025, p 242) (see section 2.2.2 below).

2.2.1. Context, objective and purpose of the Paris Agreement

Article 4.3 must be interpreted in light of the Paris Agreement’s object and purpose, which includes specific treaty provisions and the wider normative context in which the Agreement operates. This interpretive approach is consistent with the treaty interpretation rules under customary international law, as codified in Articles 31–33 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (United Nations 1969). The ICJ affirmed that several foundational principles of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) exert considerable normative influence when interpreting obligations under the Paris Agreement (ICJ 2025, para. 178). These principles include the principles of equity, common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC), the precautionary approach, sustainable development, intergenerational equity, and the duty to cooperate (ICJ 2025, paras 147–158). While these principles do not constitute ‘standalone legal obligations’, they inform the interpretation of the treaty provisions (ICJ 2025, para. 178), including the level of ambition required under Article 4.3. Thus, they are directly relevant to understanding the nature and scope of the ambition Parties are required to reflect in their NDCs.

2.2.2. Obligation to prevent significant environmental harm and the standard of due diligence

Secondly, the customary obligation to prevent significant environmental harm informs the interpretation of Article 4.3 of the Paris Agreement. The ICJ clarified that NDCs of HPA must be capable of making an adequate contribution to collectively achieving the primary global temperature goal of limiting warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels (ICJ 2025, para. 242). Parties are under an obligation to exercise due diligence when preparing and communicating their NDCs (ICJ 2025, para. 245). Given the severity and urgency of the climate crisis, this standard of due diligence is stringent. Every nation ‘has to do its utmost to ensure that the NDCs it puts forward represent its HPA in order to realise the objectives of the Agreement’ (ICJ 2025, para. 246).

To prevent significant harm to the climate system, the ICJ identified key elements of conduct required to exercise due diligence. These include the adoption of appropriate measures, reliance on the best available scientific and technological information, consistency with relevant international rules and standards, recognition of differing national capabilities, application of the precautionary principle, and the conduct of environmental and risk assessments, including appropriate notification and consultation (ICJ 2025, paras 280–299). While the precise application of these elements may vary across national contexts and evolve over time, they support the determination of whether a state has met the required standard of conduct (ICJ 2025, para. 300).

Here, we propose an operational understanding of the HPA norm through six interpretative elements, developed in light of legal clarifications offered by the ICJ’s advisory opinion. While the ICJ provided interpretative clarity on the scope of Article 4.3 of the Paris Agreement, it did not provide a structured understanding for how to operationalise the HPA when formulating or assessing an individual Party’s NDCs. In response, we propose a structured framework which provides a practical understanding of the HPA norm based on the Paris Agreement’s objective and purpose, customary obligations and insights from the best available science.

3.1. The PA-HPA framework’s pillars

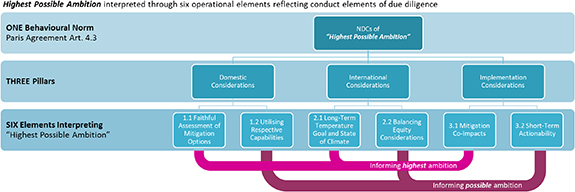

The PA-HPA framework is structured around three pillars (figure 1) integrating domestic, international, and implementation considerations. Pillar 1 on domestic considerations sets out that NDCs of HPA are to be based on a faithful assessment of mitigation options, reflecting countries’ respective capabilities. Pillar 2 on international considerations, expects the NDCs of HPA to appropriately contribute to the LTTG and balance equity considerations. Pillar 3 on implementation considerations emphasises that NDCs of HPA must consider mitigation co-impacts and must be actionable in the near term so that ambition is translated into credible action. While considerations from each element may dynamically interact, each element provides a distinct aspect to evaluating a country’s mitigation effort, enabling a careful and well-rounded assessment. Table 1 shows how elements of the framework relate to the HPA qualifiers of highest and possible. Table 2 demonstrates how the framework elements incorporate and reflect the elements of conduct required by due diligence as emphasised in the ICJ advisory opinion. The inverse mapping, from the ICJ’s elements of conduct required by due diligence to the different elements of the PA-HPA framework, is provided in supplementary information table 1 in appendix I.

Figure 1. Schematic of the Paris Agreement-Highest Possible Ambition (PA-HPA) Framework’s pillars and elements. The Paris Agreement’s norm that requires subsequent nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to be of highest possible ambition is understood as an obligation of due diligence through three pillars, which in turn are interpreted through six (three times two) context-specific elements. Engagement with the elements can be demonstrated through providing appropriate evidence. Elements 1.1, 2.1 and 3.1 are primarily informing aspects that emphasise delivering ambition that is as high as possible, while elements 1.2, 2.2 and 3.2 inform aspects that emphasise delivering on what is possible.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

Table 1. Components of highest and possible engaged by the framework. Overview of how the framework’s six elements project onto the two qualifying components of HPA: highest and possible.

Qualifying HPA componentElementExplanation Highest1.1 Faithful assessment of mitigation optionsRelative levels of ambition (incl. highest possible ambition) can only be evidenced starting from a comprehensive evaluation of economy-wide mitigation options and their costs 2.1 Long-term temperature goal and state of climateHighest ambition appropriately reflects the urgency of action to address climate change in light of international climate goals and risks 3.1 Mitigation co-impactsHighest ambition takes co-impacts (i.e., both positive or negative side effects) of NDC-related policy that could occur inside and outside of national jurisdictions into account

Possible1.2 Utilising respective capabilitiesNational capabilities inform which level of ambition can possibly be taken up in preparing and determining NDCs 2.2 Balancing equity considerationsAcknowledging justified national priorities and international circumstances informs the possible level of mitigation ambition 3.2 Near-term actionabilityReaching ambitious long-term objectives is only possible and predictable if near-term targets are immediate and actionable, aligning with future pathways

Table 2. Overview of how the PA-HPA Framework’s six elements reflect and incorporate the conduct elements required by due diligence as identified by the ICJ in the advisory opinion on states’ obligations on climate change. The PA-HPA Framework’s six elements are developed in detail in the next section. Meanwhile, the conduct elements identified by the ICJ are: ‘(i) appropriate measures’, ‘(ii) scientific and technological information’, ‘(iii) relevant international rules and standards’, ‘(iv) different capabilities’, ‘(v) precautionary approach or principle and respective measures’, ‘(vi) risk assessment and environmental impact assessment’, and ‘(vii) notification and consultation’ (ICJ 2025, paras 280–299).

PillarsInterpretative elementConduct element required by due diligence in ICJ (2025) paragraph numbers refer to ICJ (2025) 1.Domestic considerations1.1 Faithful assessment of mitigation options(i) Appropriate measures (paras 280, 282) (ii) Scientific and technological information (paras 283, 284, 286) 1.2 Utilising respective capabilities(ii) Scientific and technological information (para. 283) (iv) Different capabilities (paras 247, 290–292)

2. International considerations2.1 Long-term temperature goal and state of the climate(ii) Scientific and technological information (paras 254, 283, 284) (iii) Relevant international rules and standards (para. 287) (v) Precautionary approach or principle and respective measures (paras 293, 294) 2.2 Balancing equity considerations(iii) Relevant international rules and standards (paras 247, 248, 287, 288) (iv) Different capabilities (paras 290–292)

3.Implementation considerations3.1 Mitigation co-impacts(vi) Risk assessment and environmental impact assessment (para. 297) (vii) Notification and consultation (para. 299) 3.2 Near-term actionability(i) Appropriate measures (paras 280, 282) (v) Precautionary approach or principle and respective measures (paras 293, 294) (vii) Notification and consultation (para. 299)

3.2. The PA-HPA framework’s six elements

This section describes each of the six interpretative elements of the PA-HPA Framework: faithful assessment of mitigation options (Element 1.1), utilising respective capabilities (Element 1.2), LTTG and state of climate (Element 2.1), balancing equity considerations (Element 2.2), considering mitigation co-impacts (Element 3.1), and near-term actionability (Element 3.2).

3.2.1. Element 1.1: faithful assessment of mitigation options

NDCs reflecting HPA should be underpinned by a faithful assessment of economy-wide mitigation options and their respective costs. The adoption of ‘appropriate rules and measures,’ is a key element of conduct in exercising due diligence (ICJ 2025, para. 280). In the mitigation context, measures must ‘achieve the deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that are necessary for the prevention of significant harm to the climate system’ (ICJ 2025, para. 282). To assess which mitigation options are ‘required by due diligence’, and reasonable given a state’s national circumstances, the ICJ emphasised the importance of an assessment ‘in concreto’ (ICJ 2025, para. 137). A state cannot be considered to have acted diligently in pursuing its HPA, if it acts in bad faith or intentionally circumvents action, contrary to the knowledge provided by an assessment (Stephens and French 2016). Hence, faithful consideration of all available mitigation options forms an important procedural pre-requisite. It establishes a knowledge base that shows the mitigation option and opportunity landscape within which countries could achieve their highest ambition. While the ICJ considers IPCC reports to ‘constitute comprehensive and authoritative restatements of the best available science about climate change at their time of publication’ (ICJ 2025, para. 284), it also highlights the ‘need to acquire and analyse scientific and technological information [to be] another important factor’ (ICJ 2025, para. 283). Only through evidence-based decision-making can NDCs faithfully reflect the best effort a country can pursue, enhancing a target’s credibility and feasibility for policy implementation. Note that assessed options for lowering emissions do not have to be the outcome of explicit climate policies. They can equally be the result of non-climate policies, such as urbanisation or energy efficiency policies that are more politically palatable in certain jurisdictions (Dubash 2023).

3.2.2. Element 1.2: utilising respective capabilities

HPA should be evidenced by a consideration of respective political, legal, socio-economic, financial, and institutional capabilities6 during the NDC design. States have a common procedural responsibility to ensure that the mitigation effort outlined in their NDC reflects their highest possible level. Yet, respective capabilities and national circumstances determine the NDC targets’ substantive content. Indeed, the ICJ indicates that ‘where a State lacks the capacity to access and properly act on relevant scientific information, including when a State lacks necessary resources, failure to take appropriate preventive measures may not constitute a lack of due diligence’ (ICJ 2025, para. 283). Building on its reasoning in the Application of the Genocide Convention case, the ICJ advisory opinion affirms the strong link between states’ due diligence obligations and the CBDR-RC principle (ICJ 2025, para. 247). The obligation to prevent significant environmental harm requires each State to employ ‘all the means at its disposal’ (ICJ 2025, para. 290). Consequently, states with greater financial, technological, and institutional capabilities, subject to a more stringent due diligent obligation and consistent with Article 4.4 of the Paris Agreement, should take the lead in mitigation efforts.

At the same time, all states, regardless of their development, are expected to contribute to the highest degree possible given their respective capabilities and national circumstances (ICJ 2025, para. 291). As nations continue to economically develop, the level of diligence they are expected to exercise increases accordingly, with a categorical distinction between developed and developing countries being rejected (ICJ 2025, para. 292). However, neither limited capacity nor evolving national circumstances may exempt a state from its due diligence obligation to address climate change (ICJ 2025, para. 292). Thus, Element 1.2 of the PA-HPA Framework encourages each nation to formulate NDC targets based on the maximum level of effort it can possibly contribute as a function of its national capability, acting in good faith.

3.2.3. Element 2.1: state of the climate and the LTTG

A country’s mitigation objectives must reflect the urgency of action to meet the Paris Agreement LTTG (UNFCCC 2015, Art. 2.1.a). The current trajectory of collective emission reductions falls short of meeting this goal (Rogelj et al 2023, 2024, UNFCCC 2024a, 2024b) and the carbon budget for limiting warming to levels consistent with the Paris Agreement is shrinking rapidly (Forster et al 2025). Therefore, the risk of dangerous levels of anthropogenic interference with the climate system and of exceeding agreed-upon global warming limits is high. The intensified risk of harm that is reported by the latest IPCC Synthesis Report (IPCC 2023) compared to previous IPCC assessments7 translates in a ‘stringent’ due diligence standard attached to states domestic mitigation measures (ICJ 2025, para. 254). Interpreting Article 4.3, the ICJ’s advisory opinion emphasised that a state’s NDC must be capable of making an adequate contribution to the collective achievement of the temperature goal (ICJ 2025, para. 242), considering outcomes of the global stocktake and best available science (ICJ 2025, para. 243). Thus, setting NDC targets proportionate to the degree of urgency and climate-related harm acts as a qualifier of an ambitious NDC. It aligns ambition to be temporally representative of the best available science, which informs the overarching objective of the Paris Agreement LTTG.

3.2.4. Element 2.2: balancing equity

Highest possible mitigation ambition as a due diligence obligation must involve balancing of equity considerations. International commitments to differentiation and sustainable development, as enshrined in the Paris Agreement Articles 2, 4, the Paris Rulebook Annex I paragraph 6, and in the broader UN Sustainable Development Agenda (Rio Declaration on Environment and Development 1992, UNFCCC 2015, 2019), add a right-based component to what can be considered a country’s HPA (Rajamani et al 2021), and form a core factor for differentiating between states’ respective due diligence obligations in the climate context (ICJ 2025, para. 247). Informed by principles of CBDR-RC and equity, this element enables states to evidence how theoretical maximum mitigation capacities are balanced against what is achievable given respective socio-economic conditions, capabilities, and responsibilities. To promote the feasibility of the implementation of NDC targets, a diligent balancing of equity considerations necessitates formulating mitigation targets that account for international equity8.

3.2.5. Element 3.1: mitigation co-impacts

Mitigation objectives in NDCs reflecting HPA should seek to foreseeably account for domestic and international co-impacts. In the climate context, the ICJ clarified that due diligence involves a procedural duty to conduct an environmental impact assessment with the objective of preventing harm considering the ‘specific character of the respective risk’ (ICJ 2025, para. 297). In line with their respective due diligence obligations, the PA-HPA Framework asks ambitious NDCs to proactively assess and manage potential co-impacts and interconnected risks of the mitigation target implementation.

Beyond the domestic context, such considerations extend to preventing foreseeable adverse international co-impacts. While NDCs are by definition nationally determined with a focus on domestic mitigation (UNFCCC 2015, Art. 4.2), Article 3 of the Paris Agreement makes clear that they must be understood as contributions to the global response to climate change and ‘with the view to achieving the purpose of this Agreement as set out in Article 2’ (UNFCCC 2015, Art. 3). This is reinforced by the customary harm prevention principle emphasising that countries’ domestic activities should not cause damage outside their jurisdiction (International Law Commission 2001, p 140, 154). Furthermore, the importance of considering international co-impacts of mitigation measures in NDCs is supported by the ICJ’s advisory opinion, indicating that ‘due diligence in preventing significant harm to the environment sometimes also implies an obligation of States to notify and consult in good faith with other States with respect to risks of adverse effects of their conduct. This obligation exists where planned activities within the jurisdiction or control of a State create a risk of significant harm’ (ICJ 2025, para. 299).

Consequently, despite their nationally determined character and domestic focus (UNFCCC 2015, Art. 4.2), the PA-HPA Framework necessitates ambitious NDCs targets to foresee potential international co-impacts and notify other countries of their existence (ICJ 2025, para. 299). Such considerations may include, among others, financed, outsourced, and embedded emissions resulting from production activities in other countries, and biodiversity or food security trade-offs of climate-related trade links and further social consequences. By promoting a global perspective on ambitious mitigation actions, the framework reinforces accountability and fosters international cooperation in achieving global climate goals.

3.2.6. Element 3.2: near-term actionability

Lastly, an NDC of HPA should ensure predictability of actions by communicating decisive near-term measures. The actionability element emphasises that highly ambitious NDCs must reflect the Paris Agreement’s objective of effectiveness. Consistent with the precautionary approach, a recognised conduct element by the ICJ for determining states’ respective due diligence obligations (ICJ 2025, para. 293), a state must not delay adopting appropriate measures necessary to prevent harm to the climate system. Near-term actionability minimises the risk that efforts are backloaded to the future and addresses concerns of intergenerational equity (Bundesverfassungsgericht 2021, Minnerop 2022). Therefore, the PA-HPA Framework expects that a country’s highest possible mitigation effort will involve acting with foresight by setting proximate milestones. To reduce the risk of mitigation failure, often impacted by conceptual uncertainties and optimism biases in policy design (Workman et al 2024), a country’s best effort and NDC of HPA should evidence how near-term policy paths are aligned and can be re-aligned towards reaching long-term mitigation goals that are typically expressed in countries’ long-term low-emission development strategies (Rogelj et al 2021, 2023, UNFCCC 2023, Weitzel and Ordonez 2025). Ultimately, this element underscores the importance of temporal ambition as the foundation for sustained, credible progress towards the Paris LTTG.

Previous sections introduced the elements and structure of the PA-HPA framework and their grounding in the ICJ’s advisory opinion. Here, we reflect on its application. We begin by outlining how engagement with the framework’s elements can be sequenced in a process of setting NDCs of HPA. Following this, we reflect on potential barriers to implementation and next steps.

4.1. Practical application

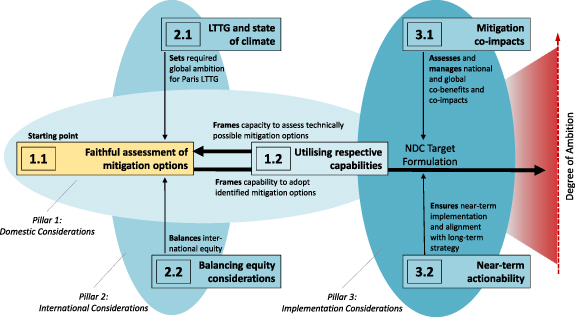

The framework presents a structured interpretation of the HPA norm in pillars and non-hierarchical elements. In the most basic sense, countries would be expected to provide evidence of having considered each element, either directly within their NDCs or through referencing external supporting documents and implementation evidence. However, applying the PA-HPA framework to determine or evaluate NDCs can be further facilitated and clarified by a stepwise approach, where elements are engaged in a logical sequence (figure 2). Pillar 1 (domestic considerations) and Pillar 2 (international considerations) are engaged together in a first step, with Pillar 3 (implementation considerations) following thereafter. This approach not only helps evidencing HPA in NDCs but also enables the transparent identification and communication of conditionality accompanying NDC targets.

Figure 2. Schematic guiding the practical application of the Paris Agreement-Highest Possible Ambition (PA-HPA) Framework. The visual outlines an illustrative sequence of and relationship between the framework’s elements introduced in figure 1. NDC stands for nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement, LTTG for the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

4.2. Sequence of elements for setting NDCs

A central starting point for the application of the PA-HPA framework is Pillar 1. Element 1.1 calls for an initial faithful assessment of domestic, economy-wide, technically feasible mitigation options and their respective costs. Such faithful assessment is modulated by Element 1.2 which is applied for the first time to ensure the respective capabilities of countries are considered. This step frames expectations regarding how elaborate or detailed a faithful assessment of mitigation options may be. The expected assessment under Elements 1.1 and 1.2 is expected not to result in a single answer but to deliver technically sound evidence for the full range of potential emission reduction and avoidance options, their socio-technical characteristics, benefits, and costs.

The deepest identified options for reducing emissions under Pillar 1 do not directly prescribe what a country’s NDC reflecting HPA would be. Initially carried out independently of considering the elements in Pillar 2 and Pillar 3, the assessed, comprehensive range of emission reduction options are subsequently interrogated and contextualised through other elements in the framework. Logically, an assessment of technical mitigation options, unconstrained by financial, societal, or political feasibility considerations, will identify options or measures that exceed an ambition level that could subsequently be deemed possible given proportionality and foreseeability considerations.

Starting from the range of technically available mitigation options, Elements 1.2, 2.1 and 2.2 are engaged to develop an evidence-based narrative, determining which mitigation options can be considered as part of a country’s NDC that reflects HPA. Element 2.1 (LTTG and State of Climate) requires countries to justify their level of ambition in the context of the global state of climate change and the urgency of action to meet the Paris Agreement LTTG. Element 2.2 (Balancing Equity Considerations) and Element 1.2 (Utilising Respective Capabilities) allow countries to reflect how justice- or other equity-based considerations impact their nationally determined choice of what the HPA level for their NDC is. In light of considerations under Elements 1.2 and 2.2, not every mitigation option that is technically available would be part of a country’s HPA. This interconnected approach ensures that the options selected for inclusion in an NDC of HPA are well-informed, well-evidenced, balanced, and aligned with both national capabilities, equity considerations, and global climate objectives.

Once an in-depth assessment identifies the highest possible levels of ambition, final engagement with Pillar 3 becomes essential to ensure an effective implementation, which reflects both temporal and spatial ambitions. By engaging Element 3.1 (Mitigation Co-Impacts), countries are asked to account for potential side-effects of their actions. Ambitious NDC targets should contribute to globally effective mitigation efforts rather than potentially frustrating them, emphasising a globally responsible approach to ambition. Under Element 3.2 (Near-Term Actionability) the identified mitigation options are translated into clear, implementable policies that can make measurable progress towards the NDC targets.

Attention to interactions among elements promotes coherence in policy and action, maximising the degree of ambition a country can possibly contribute to global mitigation efforts. States are encouraged to explicitly document choices that affect these interactions (supplementary tables 2–4 in appendix II provide some illustrative examples). This process strengthens NDC targets to be comprehensive, balanced, and aligned with both national and international climate goals.

Finally, upon conclusion of the previous steps, countries may carry out a final reflection on the equity and fairness of their NDC of HPA. By synthesising insights from all parts of the evaluation, this step reinforces fairness and aligns with the Paris Agreement’s objective of differentiation in the NDC formulation process. For instance, if a country strongly evidences ambition in Pillar 1 but provides a weak indication of balancing equity (e.g., an advanced economy which does not fully address its historical emissions), a reflection upon CBDR-RC would emphasise the need to strengthen their ambition through efforts beyond their domestic emissions.

4.3. Current considerations of HPA in NDCs

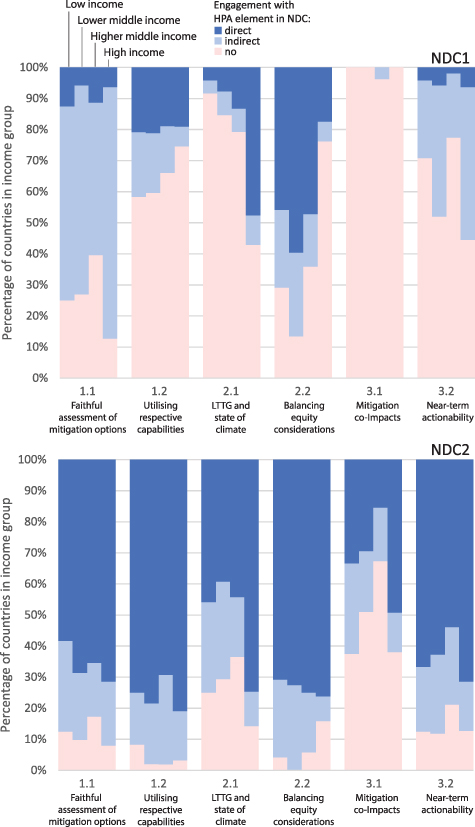

To illustrate the applicability of HPA considerations on NDCs, we carry out an illustrative analysis of the first and second rounds of NDCs (see Supplemental Data Table). This preliminary analysis shows that countries already engage with several of the elements identified by the PA-HPA Framework, with interesting variations across income groups (figure 3). The increase in engagement between the first round (submitted at the time of the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015) and the second round of NDCs (submitted around COP26 in Glasgow in 2021) also shows a clear progression, most likely because of more explicit guidance that was consolidated at CMA1 (UNFCCC 2019).

Figure 3. Mapping of the consideration of elements of highest possible ambition in first and second round NDCs. Results are shown for each framework element and for four country income groups as defined by The World Bank (2024). An emissions-weighted version of this figure is included in Annex III in Supplementary Material.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image

Initially, the highest direct engagement was seen with Elements 1.2 (Utilising Respective Capabilities), 2.1 (LTTG and State of Climate) and 2.2 (Balancing Equity Considerations). High income countries referenced Element 2.1 markedly more frequently than country groups with lower incomes. The opposite was observed for the engagement with Element 2.2 while for Element 1.2 no obvious trend across country income groups is found. The level of direct engagement increased strongly in the second round of NDCs, with many more countries engaging with Element 1.1 (Faithful Assessment of Mitigation Options) and Element 3.2 (Near-Term Actionability) as well. While virtually no NDC in the first round reflected on co-impacts of the proposed actions (Element 3.1), a clear improvement can be seen in the second iteration. As countries have explicitly been requested to clarify how new NDCs are considered fair and ambitious (UNFCCC 2019) increased engagement with the elements identified in the framework is expected from future submissions.

4.4. Reflections on effective application

The effective application of the PA-HPA Framework will be impacted by countries’ capabilities and national circumstances. For example, the disparity in data availability and quality across regions will affect the degree to which countries can engage with Elements 1.1 and 3.1 of the framework. Uneven data availabilities between countries limit the possibility of a fully standardised benchmark approach. The PA-HPA Framework is therefore designed to provide adaptable guidelines and indicators which allow for context-specific data use while maintaining transparency and promoting alignment towards a common understanding of HPA. Furthermore, while the HPA norm in the Paris Agreement applies to mitigation (Article 4), an all-encompassing evaluation of the best mitigation effort will always consider trade-offs and synergies with a set of other policies focussed (e.g. development or adaptation). As such, the PA-HPA Framework does not prescribe a climate-focus in domestic policymaking, but rather allows for the consideration of a wide-ranging set of policies that deliver national different priorities (Dubash 2023). The PA-HPA Framework requests, however, that for the purpose of evidencing HPA in NDCs, these various policies are reflected on from a climate change mitigation perspective.

Varying interpretations of equity and fairness in evaluating adequate mitigation contributions are expected. As equity and fairness are value-based metrics, the framework does not recommend a single interpretation under Element 2.2 (Balancing Equity Considerations). Instead, it encourages countries to clearly define the equity principles and related approaches that are followed (Pelz et al 2024) within their submissions. A transparent demonstration of how a country has balanced mitigation options with equity considerations, given its chosen metrics, promotes a coherent application of the framework while allowing for national differences. Because of the structured engagement with technical (Element 1.1) and other evidence that relates to equity (Elements 1.2 and 2.2), a diligent application of the PA-HPA Framework would also facilitate the transparent communication of means (be they financial or otherwise) to increase the ambition of targets included in NDCs. Indeed, by laying out the assessed barriers to taking up deeper emission reduction targets, conditionality linked to strengthening NDCs beyond their unconditional targets can be practically understood, discussed, and potentially addressed.

National circumstances are also subject to change, and evaluations of HPA must therefore remain dynamic and adaptive. To achieve this, countries are encouraged to introduce regular internal review cycles (e.g., undertaken by climate advisory boards), allowing for the re-evaluation of national circumstances and mitigation efforts. These review cycles could align with the five-yearly frequency set by the Paris Agreement’s ratcheting cycles.

The PA-HPA Framework presented here aims to provide a structured way for countries to approach the integration and communication of HPA in their NDCs. The framework starts with an interpretation of HPA based on the authoritative guidance provided by the ICJ’s advisory opinion. It draws upon well-established environmental legal principles, due diligence obligations in the climate context and places a logical focus on climate-related outcomes. However, the PA-HPA Framework is also designed to be useful in jurisdictions where climate and emissions are not as central to the policy landscape. Its strength lies in establishing an operational understanding of the HPA norm that allows countries and other stakeholders to engage constructively. In the context of an ever-increasing urgency to take up ambitious climate actions, the PA-HPA Framework supports countries in pursuing their best efforts and HPA in successive NDC submission cycles. It also facilitates transparent communication of the conditions under which more ambitious targets can be pursued. Finally, it empowers societal stakeholders to interrogate, verify and, when necessary, challenge whether successive NDC preparations were carried out with due diligence. As a tool, it can be explored by civil society, supporting accountability and transparency in global and national climate action.

The authors thank N.J. Schrijver, A. Savaresi and various anonymous reviewers for their engaging and constructive feedback.

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article (and any supplementary files).