Late August days were once bittersweet for me. Growing up on the Jersey Shore, where my family were members of a rickety old beach club, I still remember the feel of the cooler air in the evenings as I pulled on a sweatshirt and buried my feet in the sand. I learned to swim at that club, to body surf, to enjoy the march of near-naked beachgoers dragging umbrellas, folding chairs, coolers, and various flotation devices across the sand. I wanted those end-of-summer days to go on forever, knowing a return to school—to an indoors life—was around the corner.

Article continues after advertisement

Moving to New York City in my early twenties, I found my beach at Fort Tilden, on the Rockaway Peninsula. I had thought all beaches were raked like sand traps; you mean they should have dunes? I …

Late August days were once bittersweet for me. Growing up on the Jersey Shore, where my family were members of a rickety old beach club, I still remember the feel of the cooler air in the evenings as I pulled on a sweatshirt and buried my feet in the sand. I learned to swim at that club, to body surf, to enjoy the march of near-naked beachgoers dragging umbrellas, folding chairs, coolers, and various flotation devices across the sand. I wanted those end-of-summer days to go on forever, knowing a return to school—to an indoors life—was around the corner.

Article continues after advertisement

Moving to New York City in my early twenties, I found my beach at Fort Tilden, on the Rockaway Peninsula. I had thought all beaches were raked like sand traps; you mean they should have dunes? I loved the relics of Fort Tilden’s past, the large concrete batteries and bunkers that were being swallowed up by vegetation.

It was still partly a fishing beach then—this was 20 years ago—but it was fast becoming a hipster haven. Behind my sunglasses, the people-watching was great. I would spend hours diving under and riding waves, same as I had as a kid. And in the last days of August, laughter and pot would waft over the scene, happiness laced with sadness.

The fall months on the Atlantic Coast are a phenomenal time to watch migratory birds.

But I no longer mourn the end of summer. In fact, I start to look forward to it, and that has nothing to do with my dermatologist’s warnings. I think the best days on the beach come after Labor Day, when the human crowds leave and a new crowd arrives.

This crowd travels lighter than beachgoers. It comes in waves, pushed on by cooler winds from the north and journeying farther than any of us will in our lifetimes. It just passes through, not like the beach bums of summer, and though it doesn’t exactly know where its trip will end, it will recognize that place when it arrives. This crowd is made up of several hundred species of migratory birds, millions of individuals, that each autumn fly south as far as southern South America. And the beach is prime viewing for the sky show.

Article continues after advertisement

The fall months on the Atlantic Coast are a phenomenal time to watch migratory birds. New York is a crossroads for them at the edge of the continent, like a traffic circle with east-west routes running along the ocean or north-south routes going up the harbor or to New Jersey. That geography does wonders for people who want to watch birds—around 20 million migrate through New York in the fall. Over 400 species have been documented in the city, far more than in Yellowstone or any other national park.

Fort Tilden, I learned, is a place to see that migration in action; to see birds as they negotiate land, water, and wind; to see a great diversity of them at once.

The fall and winter offer the best swells of the year, turbocharged by nor’easters and tropical storms.

Every October, I make a point of joining the Queens County Bird Club’s annual “Big Sit” at the beach, in which the goal is to count as many species as possible from one spot—in this case, a wooden deck on top of a concrete gun battery. When I joined it two years ago, the group, which included several Queens birders who’d been there since before sunrise, found over 90 species in one day.

When I became a birder, I began to see the beaches of my youth and the coastal environment in a more complete way—as an ecosystem filled with all kinds of life. The human throngs in the summer are one part, too often the only one we see. The honks of wild Canada geese, for instance, fresh out of the Arctic and now high in the clouds going south, signal a change in seasons for me. Thousands of tree swallows float down the coast, rising into snow globe formations when a deadly falcon appears on the scene.

And they have a right to be wary—hundreds of hawks, falcons, eagles and ospreys wing past you on a good fall day. From that deck, I have watched dolphins leap after large schools of menhaden, and a humpback whale breach close to shore, body slamming those fish as they shimmered on the surface.

Article continues after advertisement

I found that paying attention to this theater playing out in the skies and shores inevitably opened me up to other unexpected pleasures, an opening of all my senses. In October, the dunes flare with goldenrod and the bronze of bayberry. The air is scented with the aroma of pitch pines warmed by the low sun. And on the beach you can walk for miles without having to snake around umbrellas or tents, hearing the waves crash onto shore. I might see surfers out there, too. The fall and winter offer the best swells of the year, turbocharged by nor’easters and tropical storms.

The beauty of fall keeps me coming back even in the winter. In January and February, I like to walk from Fort Tilden to Breezy Point, the western tip of all Long Island, an eight-mile loop on the sand. I carry a thermos of tea or coffee, bundled in layers, and picnic on a far rock jetty.

Spring is here, and some of the birds I watched in the fall are beginning to return.

It’s a good place to scan for sea ducks and razorbills, the closest relatives to the extinct great auk; they look like black footballs, flying low over the waves. Flocks of snow buntings skitter across the sand, rising in confetti clouds. Snowy owls show up often enough for me to inspect with my binoculars every white plastic bag I see at a distance in the dunes.

And in late March and early April, when the winds still bite, the first piping plovers, tiny and sand-colored, return to the Rockaways. They are the only endangered bird that makes its nest in New York. Spring is here, and some of the birds I watched in the fall are beginning to return.

But eventually the place will not be entirely theirs. The human theater will play out on the sand, the smell of sunscreen will fill the air, and the piping plovers and other beach birds will crowd into the little spaces left for them. I’ll join in the revelry, but deep down I’ll anxiously await when I can return to Fort Tilden after Labor Day, climb the wooden steps to the top of that gun battery, and look up as thousands of birds fly over my head.

Article continues after advertisement

__________________________________

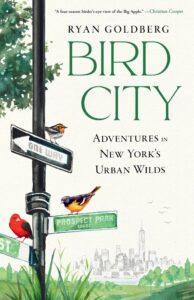

Bird City: Adventures in New York’s Urban Wilds by Ryan Goldberg is available from Algonquin Books, an imprint of Hachette.