This feature first appeared in October 2024 on Londonist: Time Machine, our much-praised history newsletter. To be the first to read new history features like this, sign up for free here.

Image: Matt Brown

Image: Matt Brown

👆 This is the spot where, 200 years ago, the idea of lifeboats was floated.

Not this exact building, which is now a branch of HSBC, but its predecessor. Here, at the bottom end of Bishopsgate, stood the City of London Tavern — usually called The London Tavern. It is arguably the most important London building that nobody has heard of...

This feature first appeared in October 2024 on Londonist: Time Machine, our much-praised history newsletter. To be the first to read new history features like this, sign up for free here.

Image: Matt Brown

Image: Matt Brown

👆 This is the spot where, 200 years ago, the idea of lifeboats was floated.

Not this exact building, which is now a branch of HSBC, but its predecessor. Here, at the bottom end of Bishopsgate, stood the City of London Tavern — usually called The London Tavern. It is arguably the most important London building that nobody has heard of.

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), as we now call it, was founded on this spot on 4 March 1824. Its mission was simple: to reduce the appalling death toll from shipwrecks in British waters. No lesser figure than the Archbishop of Canterbury sat in the Chair.

The UK now has over 400 lifeboats. Their launch can be traced back to that early spring meeting in the London Tavern, two centuries ago.

Image: Matt Brown

Image: Matt Brown

The London Tavern could be rightfully proud if that was the only meeting of note upon its premises. But so much happened here it could carry a dozen memorial plaques.

Also in 1824 — just a couple of weeks before the lifeboat meeting — a key moment in the history of London transport and engineering took place at the Tavern. It was here that Marc Brunel held the first public meeting for his proposed Thames Tunnel. This was an audacious venture to build the world’s first tunnel beneath a major river. It would take 20 years to complete.

The Thames Tunnel, featuring a cameo (left) from somebody’s nose. Image: Matt Brown

The Thames Tunnel, featuring a cameo (left) from somebody’s nose. Image: Matt Brown

The tunnel between Wapping and Rotherhithe is today part of the Windrush line (formerly the London Overground), still going strong two centuries after Brunel first pitched it at the London Tavern. 1,381 shares were bought that day, getting the project off to a sound financial start. Incidentally, Brunel’s better-known son Isambard was back at the London Tavern in 1839 to decide upon the gauge of track to use on the Great Western Railway.

The Grandest Tavern in all Europe

By this time, the London Tavern was already well established as a meeting place for all kinds of venture. This was the venue of choice if you wanted to set up a charity, form an interest group or gain seed funding for a new business.

The first London Tavern, whose origins are mysterious, was lost to a devastating fire in 1765, a fire which took out most of the block. The tavern was quickly rebuilt to the designs of Richard Jupp, who is perhaps best known as the architect of Severndroog Castle, as well as the chapel to Guy’s Hospital. It reopened in 1768 when it was described by one newspaper as “the grandest tavern in all Europe”.

The name ‘Tavern’ here is somewhat misleading. This was not some cosy, folksy place where you might exchange banter with the stout yeoman of the bar, or share a pint beside a roaring fire. No, this was a splendid banqueting hall, richly decorated with swags, garlands, paintings and drapery. It was custom-built for dinners and gatherings, with an army of 60 catering staff. Gibson Hall, which still stands a few doors down from the site, is perhaps the closest comparison.

Interior of the London Tavern. The image shows a dinner in celebration of the emancipation of Holland from France, on 14 December 1813. Image: Public domain

Interior of the London Tavern. The image shows a dinner in celebration of the emancipation of Holland from France, on 14 December 1813. Image: Public domain

Such was the kitchen’s reputation that other banqueting houses ordered takeaways. The largest order of all came in 1837, for a Royal Banquet at Guildhall, attended by Her Youthful And Newly Minted Majesty Queen Victoria. The vast order is enough to make us vegetarians weep. 1,100 pints of turtle soup, for starters. For the mains, 60 roast turkeys were supplied, along with 80 pheasants, 10 leverets, 40 partridges, 40 fowl, and a motley Noah’s ark of auxiliary butchery. This was a culinary powerhouse. Labelling it a ‘tavern’ is like calling Henry VIII’s palace Hampton Court Bedsit.

Not-so-Humble Beginnings

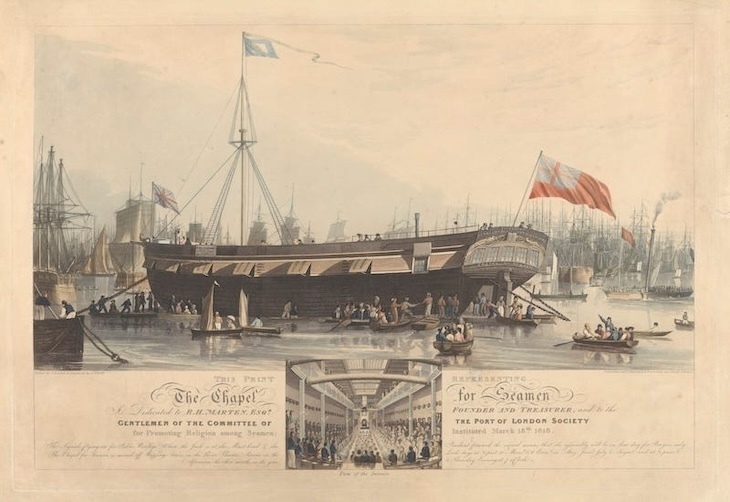

The London Tavern was the sparkly launchpad for many other ventures over the decades. One notable charity, still with us today, was the Sailors’ Society, founded at the London Tavern in 1818 as the Port of London Society. It initially worked to provide religious facilities for seafarers, including this extraordinary floating ‘Chapel for Seamen’ which was moored off Wapping. I think this deserves an article in its own right some time:

Image: Public Domain

Image: Public Domain

The society would go on to build less buoyant hostels and retirement homes for sailors. One of its most noteworthy London projects was the Mission Building in Limehouse, which still dominates the eastern end of Commercial Road a century after it was built.

Any cricket fans in the house? The London Tavern was the place where, on 15 December 1863, the Middlesex County Cricket Club was founded. This famous club plays at Lord’s cricket. It has won countless trophies and outlived its namesake county by 60 years. And it all began at the London Tavern.

We could add the influential “London Institution” to our growing list. This was launched at the London Tavern in 1805 “to promote the diffusion of Science, Literature and the Arts”. It is long defunct, but its vast collection of books would go on to seed the School of Oriental and African Studies and augment the Guildhall Library.

Many of the meetings at the tavern were gentlemanly affairs, with few women in evidence. However, as the Tavern grew in reputation as a venue for charity meetings, we do find accounts of women in attendance. The venue also hosted regular balls and even Jewish weddings.

The Tavern was particularly noted for its political gatherings. One of the earliest recorded here is the 1769 foundation of the Society of Gentlemen Supporters of the Bill of Rights (or SOGSOBOR, as they probably didn’t call themselves). This group were tub-thumpers for John Wilkes, the radical MP who stood up for voters’ rights but was expelled from the House of Commons. The meeting raised some £1,500 to help Wilkes with his debts and legal costs.

The Tavern would go on to host countless political rallies, including meetings in support of the French Revolution, and gatherings to discuss the ‘Eastern Question’ — Turkey’s invasion of Russia in 1853 which sparked the Crimean War. After the House of Commons, this venue probably saw more heated debate than any other room in the kingdom.

A Dickensian tragedy

The venue almost became a metonym for gentlemanly gatherings. Its reputation even spilled over into fiction. Charles Dickens used the venue for a shareholder meeting of the “United Metropolitan Improved Hot Muffin and Crumpet Baking and Punctual Delivery Company”, a delicious parody of the long-winded names of business ventures of the day (and also a burlesque of the opium trade, such was the author’s genius).

Dickens was himself a regular visitor to the London Tavern. In 1843 he spoke as Chair of the Printers’ Pension Society. He returned each year to host the General Theatrical Fund Association’s dinner, also held in the tavern. It was while giving that address in 1851 that tragic news reached the author. Earlier that day, after Dickens had left home for the tavern, his infant daughter Dora had died suddenly after experiencing convulsions. Word was sent to the tavern. Dickens was busy preparing his talk, and so the messenger spoke with John Forster, Dickens’s close friend. Forster agonised about when to break the awful news:

”I satisfied myself that it would be best to permit his part of the proceedings to close before the truth was told to him. But as he went on, after the sentences I have quoted, to speak of actors having to come from scenes of sickness, of suffering, aye, even of death itself, to play their parts before us, my part was very difficult.”

Dickens was crushed by the loss, as were the whole family. But he didn’t let any tragic associations with the London Tavern prevent him from returning. He was back the next year to host the annual dinner of the Gardeners’ Benevolent Institution. In 1854 he toasted the room at a meeting for Commercial Travellers’ Schools. In 1857 he chaired a meeting of the Clerks’ Schools for Orphan and Necessitous Children. And in 1866, showing the great variety of his interests, he oversaw a dinner for oarsmen, under his role as President of the Nautilus Rowing Club. And you think you’re busy.

The London Tavern closed forever in 1876 after a downturn in business. Its fittings and furnishings were sold off, including a great deal of vintage wine from the early years of the century. The building was bought by the neighbouring Royal Bank of Scotland and immediately knocked down, to make way for an extension to the bank. It remains in banking use, but now under HSBC.

Today, there is nothing on the building at 1-3 Bishopsgate to remember this remarkable venue. The London Tavern has fallen out of popular memory, despite the central place it once held in public discourse. I think it deserves one of those blue-glaze City of London memorial plaques. If only there was somewhere we could organise a supporters’ meeting to petition for one!