Table of Contents

Few years ago, I have discovered a programming language called Zig, as a C programmer it has given me the opportunity to write reliable, fast code while being more productive. "Why not Rust?" you may ask. Well, I don’t like Rust that much, that said I won’t dislike you for using it! Zig was giving me joy, not to mention the better cross-compilation it offered, but there was something missing, something off. Ignoring all the issues, high verbosity (e.g. when casting) and breaking changes present in every new Zig release; it was C syntax, I simply kept returning to writing C because it was simple and intuitive for my brain to write...

And then something happened... [Tsodi…

Table of Contents

Few years ago, I have discovered a programming language called Zig, as a C programmer it has given me the opportunity to write reliable, fast code while being more productive. "Why not Rust?" you may ask. Well, I don’t like Rust that much, that said I won’t dislike you for using it! Zig was giving me joy, not to mention the better cross-compilation it offered, but there was something missing, something off. Ignoring all the issues, high verbosity (e.g. when casting) and breaking changes present in every new Zig release; it was C syntax, I simply kept returning to writing C because it was simple and intuitive for my brain to write...

And then something happened... Tsoding made a stream about C3 (VOD). At the time I was a Zig & C fanboy. C3 didn’t click with me at first, having the need to use fn was a bit strange to me, or the enforced code style: e.g. PascalCase for types, SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE for constants, etc...

Spoiler alert: I changed my mind!

Drinking C3 Capri-Sun #

(You thought I was gonna say Kool-Aid? HA! but I’m not an American)

At the time I was working on a project called sc, my own challenge to make a small Scheme-like dialect in less than 1000 lines, I was mostly successful, however it had UB. Later, I thought about giving C3 a try, why wait till it gets better? I’ll use it now, possibly contribute and learn something new! And maybe make a new Scheme-like dialect, but not as a challenge. So I joined C3’s discord server...

First steps were rough, especially getting familiar with the language. It looks like better C, but it was a whole new experience for me! I had to look at the documentation a lot (which is apparently dated!) and read the source code of the standard library, which went quite okay considering I learned that ability from Zig!

During the familiarization stage of the language, I got a lot of help from Christoffer Lerno himself. I have learned about the @pool temporary allocator, when to use methods and bunch more cool things I get to enjoy about the language.

The Features #

Now I’m going to list feature I like about the language with further detail.

Temporary Allocator #

In C3, you can simplify the memory management of temporary allocations using the @pool temporary allocator macro. This macro makes memory management more convenient as you don’t have to manually manage the temporary allocated memory. Yes, you can do this in C, Zig, etc just fine by using an Arena Allocator. However you also need to initialize/free the arena, costing you few extra lines.

Code sample:

fn void foo()

{

@pool() {

bar();

};

// All temporary allocations inside of bar

// and deeper down is freed when exiting the '@pool' scope.

}

In the standard library functions/methods that require an Allocator use the prefix "t" to symbolize the usage of the temporary allocator. If a such function/method were missing, you can provide the temporary allocator using the global variable "tmem". (For a normal (libc) allocator you can use the global "mem" instead)

Flexible Modules #

In Zig a file counts as a module, you cannot freely split it across files. Well, yes you can, but you’ll just end up nesting them. C3 modules feel kinda like C++ namespaces - a module can be extended and split across many files, heck you can define multiple modules in a single source file! Isn’t that convenient?

Module Declaration #

To declare a module, you can use the module statement, e.g. module foo;

Nesting of modules is also supported with the :: separator, e.g. module foo::bar::baz;.

Module Imports #

To import a module, you can use the import statement, e.g. import std::collections::list. Imports are always recursive, meaning sub-modules get imported as well:

foo.c3

module some::foo;

fn void test() {}

bar.c3

module bar;

import some;

// import some::foo; <- not needed, as it is a sub-module to "some"

fn void test()

{

foo::test();

// some::foo::test() also works.

}

What about types? Types in modules are usually imported into the global scope, which can cause issues such as duplicate types. To prevent these issues, you can use the module path when resolving the type:

abc.c3

module abc;

struct Context {

int a;

}

de.c3

module de;

struct Context {

void *ptr;

}

test.c3

module test1;

import de, abc;

// Context c = {} <- ambiguous

abc::Context c = {};

Module Limits #

Module names in C3 are limited only to lowercase characters + underscore and each module name can be up to 31 characters long.

Flexible Types #

Unlike Zig, C3 allows you to define macros/methods on types from multiple files/modules & implement interface methods using the @dynamic attribute.

Methods #

Methods look exactly like functions, but are prefixed with the type name and is invoked using dot syntax:

struct Point {

int x;

int y;

}

// 'Point *self' is the same as '&self'

// 'Point self' is the same as 'self'

fn void Point.add(Point *p, int x, int y)

{

p.x += x;

p.y += y;

}

fn void example()

{

Point p = { 1, 2 };

// with struct-functions

p.add(10, 10);

// Also callable as:

Point.add(&p, 10, 10);

}

C3 offers a bit more features to functions/methods, to which I’ll get to later.

Interfaces #

Interfaces my beloved! Yes yes, Zig has tagged unions for this, but those are less flexible than interfaces in general. Interfaces in C3 work in similar way any type does, think of any as typed void *.

Defining & Implementing an interface #

An interface can be defined like so:

interface MyName {

fn String myname();

}

interface VeryOptional {

// mark interface method as optional, making it not require the implementation

fn void do_something() @optional;

}

To declare a type that implements an interface, add it after the type name:

struct Baz (MyName) {

int x;

}

// Note how the first argument differs from the interface.

fn String Baz.myname(&self) @dynamic

{

return "I am Baz!";

}

This way if type Baz didn’t implement the method "myname" it would count as compile time error.

Interfaces can also be implemented on already existing types, you just won’t get the benefits of compile time checks.

A method must be declared with the @dynamic attribute when implementing a method of an interface.

Referring to an Interface by Pointer #

An interface, e.g. MyName, can be cast back and forth to any, but only types which implement the interface completely may implicitly be cast to the interface:

Bob b = { 1 };

double d = 0.5;

int i = 3;

MyName a = &b; // Valid, Bob implements MyName.

// MyName c = &d; // Error, double does not implement MyName.

MyName c = (MyName)&d; // Would break at runtime as double doesn't implement MyName

// MyName z = &i; // Error, implicit conversion because int doesn't explicitly implement it.

MyName z = (MyName)&i; // Explicit conversion works and is safe at runtime if int implements "myname"

Calling Dynamic Methods #

There isn’t a big difference between dynamic and normal methods, you can call them directly like a normal function too! They just offer the benefit of being callable from an interface:

fn void whoareyou(MyName a)

{

io::printn(a.myname());

}

// if a method on an interface is declared optional with '@optional'

fn void do_something(VeryOptional z)

{

if (&z.do_something) {

z.do_something();

}

}

fn void whoareyou2(any a)

{

// Query if the function exists

if (!&a.myname) {

io::printn("I don't know who I am.");

return;

}

// Dynamically call the function

io::printn(((MyName)a).myname());

}

fn void main()

{

int i;

double d;

Bob bob;

any a = &i;

whoareyou2(a); // Prints "I am int!"

a = &d;

whoareyou2(a); // Prints "I don't know who I am."

a = &bob;

whoareyou2(a); // Prints "I am Bob!"

}

Contracts #

Contracts are optional pre- and post-condition checks that the compiler can use for runtime checks, optimizations, etc. Be aware the compiler may optimize some away, ensure you are using safe mode of the compiler so they are checked during runtime.

Code sample:

<*

@require foo > 0, foo < 1000 : "optional error msg"

*>

fn int test_foo(int foo)

{

return foo * 10;

}

fn void main()

{

test_foo(0); // c3c will raise an error

}

<*

@require foo != null

@ensure return > foo.x

*>

fn uint check_foo(Foo *foo)

{

uint y = abs(foo.x) + 1;

// If we had row: foo.x = 0, then this would be a runtime contract error.

return y * abs(foo.x);

}

You can read more about contracts here.

Honorable Mention #

I’m starting to realize that listing all the features would make the blog post exponentially longer, it’s quite long already! This isn’t the C3 documentation %@#* it!

I’ll just list the features I’d like to mention and provide you with a link to the documentation page so you can read them during your spare time:

- Attributes (documentation)

- Generics (documentation)

- Lambdas (documentation)

- Macros (documentation)

- Reflections (documentation)

- Simpler C Interopt (documentation)

- Strings (documentation)

- Vectors (documentation)

The Quirks #

Just like all the good things, C3 isn’t all sunshine and rainbows, and that’s okay, not everyone likes the same things, has same thoughts and so on.

Here is a list of things I find odd and don’t like about C3:

Hello... C Enums? #

C3 does have enums, they were re-worked from the ground up. Don’t get me wrong, they are indeed quite powerful, but by default they don’t share the same behavior to C enums. To achieve such behavior, you’ll have to write a new type of enum called a "const enum":

extern fn KeyCode get_key_code();

enum KeyCode : const CInt {

UNKNOWN = 0,

RETURN = 13,

ESCAPE = 27,

BACKSPACE = 8,

TAB = 9,

SPACE = 32,

EXCLAIM, // automatically incremented to 33

QUOTEDBL,

HASH,

}

fn void main()

{

int a = (int) KeyCode.SPACE; // assigns 32 to a

KeyCode b = 2; // const enums behave like typedef and will not enforce that every value has been declared beforehand

KeyCode key = get_key_code(); // can safely interact with a C function that returns the same enum

}

This however wasn’t always the case, before we got "const enums" we either had to rely on global constants or simply deal with the extra added abstraction. Just a slight warning for people who want C style enums!

Here is the documentation page to learn more about enums.

Misleading naming #

Okay, I get it, naming is hard! And yes, this is also likely my fault coming from Zig and a bit of Rust. I’m sure you’ll understand some of my struggles when you decide to learn C3 too.

Optionals are not really Optionals? #

Citing the documentation: "Optionals are a safer alternative to returning -1 or null from a function, when a valid value can’t be returned. An Optional has either a result or is empty. When an Optional is empty it has an Excuse explaining what happened."

...

...

...

...

...

ERROR: Does Not Compute

Segmentation Fault

...

Hey Oxy! Can you pull up the definition of the word "optional" in programming context for me? Thank you!

Citing Wikipedia: *"In programming languages (especially functional programming languages) and type theory, an option type or maybe type is a polymorphic type that represents encapsulation of an optional value; e.g., it is used as the return type of functions which may or may not return a meaningful value when they are applied. It consists of a constructor which either is empty (often named

Citing Wikipedia: *"In programming languages (especially functional programming languages) and type theory, an option type or maybe type is a polymorphic type that represents encapsulation of an optional value; e.g., it is used as the return type of functions which may or may not return a meaningful value when they are applied. It consists of a constructor which either is empty (often named None or Nothing), or which encapsulates the original data type A (often written

Just

A

or Some A)." *

So this means an optional is either something or nothing. But that’s not a case in C3... it’s something or something. The

Excuse

is also kinda a value, not the state of "nothing-ness".

Rust has something similar to C3, it’s called Result, good name Rust!

So a pipe is a file #

If you are just as confused as I am, that’s correct! As I was implementing syntax highlighting for codeblocks on my website, I thought of using io::read_fully function from io/stream.c3 which expects an object implementing the InStream interface. I got stdout from spawned SupProcess and passed it into the function, however I was faced with io::FILE_IS_PIPE fault???

What happened? Let me show you the source code of the function:

io/stream.c3

<*

@require @is_instream(stream)

*>

macro char[]? read_fully(Allocator allocator, stream)

{

usz len = available(stream)!;

char* data = allocator::malloc_try(allocator, len)!;

defer catch allocator::free(allocator, data);

usz read = 0;

while (read < len)

{

read += stream.read(data[read:len - read])!;

}

return data[:len];

}

This looks mostly fine... until you realize the function available is returning size? Let’s look at the available function:

io/stream.c3

fn usz? available(InStream s)

{

if (&s.available) return s.available();

if (&s.seek)

{

usz curr = s.seek(0, Seek.CURSOR)!;

usz len = s.seek(0, Seek.END)!;

s.seek(curr, Seek.SET)!;

return len - curr;

}

return 0;

}

Sigh, there it is, seeking inside a stream, NOW that’s not really an issue if your input stream is a file... not really a case for a pipe, then let’s have a look at stdout method of SubProcess:

os/subprocess.c3

fn File SubProcess.stdout(&self)

{

if (!self.stdout_file) return (File){}; // Return an empty File struct

return file::from_handle(self.stdout_file);

}

And would you look at that? stdout is treated as a file whether it’s an actual file or a pipe! I have already filed an issue for this.

What about the Scheme-like dialect? #

I have worked on it and even streamed the progress of it! You can find the first stream here. And if you’re interested in the rest of the VODs, you can find them all here. I plan on working on it and streaming some more soon!

Contributions to C3 #

As I was starting to get familiar with the language, I have started contributing back, whether it were issues, pull requests, projects or sharing the good word.

Pull Requests #

Just to name a few:

You can find full lists of issues and pull requests here:

Projects in C3 #

Projects

OpenPNGStudio - Create & stream PNGTuber models

Schem - Scheme-like dialect written in C3

Novacrash - A simple and configurable GUI panic handler for C3

Ev - Event loop implementation in C3

lowbytefox.dev - This website is written in C3

Patterngen - Generate random patterns based on seed

Si18n - A simple, compiled internationalization library for software translations

I’m slowly progressing on these projects, most are dependencies for OpenPNGStudio as I’m trying to rewrite the whole project from C to C3!

(OpenPNGStudio was supposed to be rewritten to Zig, but I liked C3 more)

Summary #

Zig is a solid choice for C programmers as it’s more battle tested, has bigger and stronger community, however don’t sleep on C3 either, give it a chance! Things are rough now, but by using it and reporting issues you contribute to the project and help it become better! C3 community may be small, but we strive to help C3 grow, make it more known, fun and simple to use.

Sources:

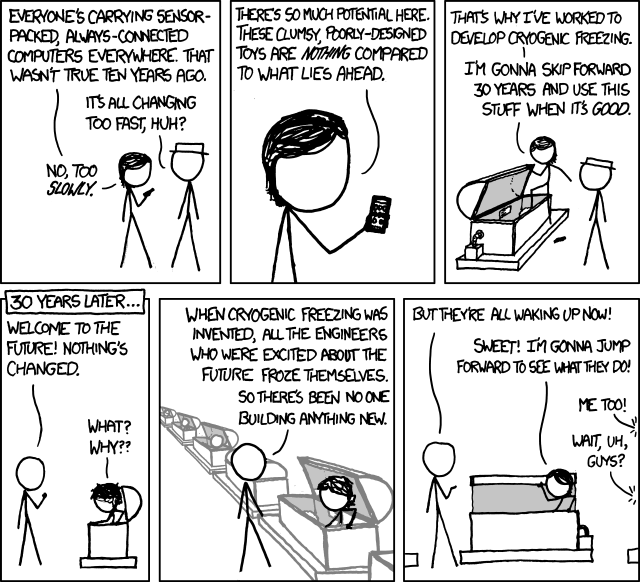

XKCD 989

XKCD 989

Hope you had fun time reading, until next time!

Copyright © 2025 LowByteFox, all rights reserved. All opinions on this website are my own, they do not represent anyone in the past, present nor the future.