📖 tl;dr: With the rise of LSPs, query-based compilers have emerged as a new architecture. That architecture is much more similar and also different to Signals than I initial assumed them to be.

Over the winter holidays curiosity got the better of me and I spent a lot of time reading up on how modern compilers achieve interactivity in the days of LSPs and tight editor integrations. And it turns out that modern compilers are built around the same concept as Signals in UI rendering, with some interesting different design choices.

Old Days: The Pipeline Architecture

The classic teachings about compilers present them as a linear sequence of phases that code runs through until you end up with the final binary. Writing a compiler this way is pretty straight forward, assuming that the l…

📖 tl;dr: With the rise of LSPs, query-based compilers have emerged as a new architecture. That architecture is much more similar and also different to Signals than I initial assumed them to be.

Over the winter holidays curiosity got the better of me and I spent a lot of time reading up on how modern compilers achieve interactivity in the days of LSPs and tight editor integrations. And it turns out that modern compilers are built around the same concept as Signals in UI rendering, with some interesting different design choices.

Old Days: The Pipeline Architecture

The classic teachings about compilers present them as a linear sequence of phases that code runs through until you end up with the final binary. Writing a compiler this way is pretty straight forward, assuming that the language is reasonably simple (JavaScript is ridiculously complex and the opposite of simple).

Source Text -> AST -> IR -> Assembly -> Linker -> Binary

First, source code is transformed into an Abstract Syntax Tree (=AST) which transforms the input text into structured objects/structs. It’s the place where syntax errors, grammar errors and those kinds of things are caught.

For example: This JavaScript source code...

const a = 42;

...is transformed into something similar to this AST:

{ "type": "VariableDeclaration", "kind": "const", "declarations": [ { "type": "VariableDeclarator", "id": { "type": "Identifier", "name": "a" }, "init": { "type": "NumericLiteral", "value": 42 } } ]}

The AST is then pushed through a few more steps until we end up with the final binary.

The actual details of these steps are not important for this blog post and what we described here is very oversimplified. But it’s important to know that compilers typically run code through a bunch of different stages until code can be executed. Doing all of this takes time. Too much time to run on every key stroke.

Modern: Query Based Compilers

When a developer changes a single file by typing a single letter, there is a lot of work going on behind the scenes. Ideally, you want to do as little work as possible. Sure, you could add caches to every stage and try to come up with a good heuristic of when to invalidate them, but it becomes difficult to maintain pretty quickly. That’s not good.

The key shift in compilers is to not think of them as just a pipeline of transformations, but as a thing you can run queries on. When a user is typing in their editor the LSP asks the editor what are the suggestions at this specific cursor position in this file? When you click "Go to Definition" on an identifier you’re asking the compiler to return the jump target (if any).

Essentially, questions are a bunch of queries that you run against your compiler and the compiler should only focus on answering these as quickly as possible and ignore the rest.

This mental shift is what makes modern compilers much more interactive. But how do they do that under the hood and what has this to do with signals?

Queries, Inputs and the Database

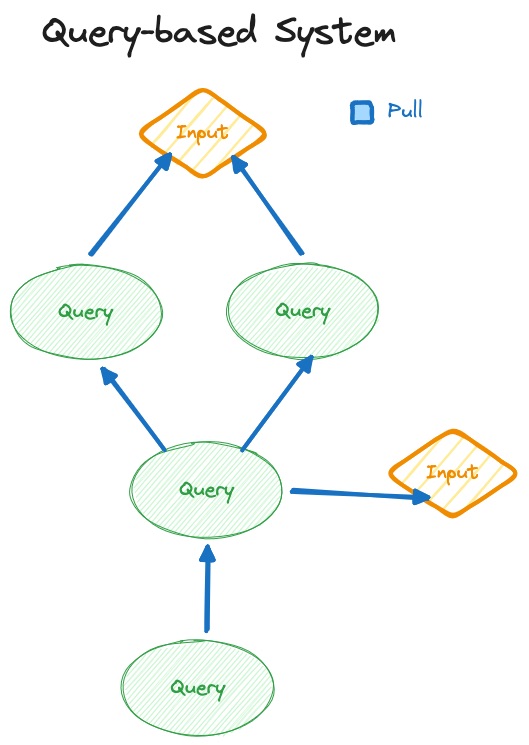

Query-based compilers have three key building blocks: Queries, Inputs and a "Database". The core idea is that everything, literally everything, is composed out of queries and inputs. Nothing runs out of the box unless a query is executed.

There is one big query at the top that says "Give me the final binary", this query then fires off multiple other queries like "Give me the IR", "Give me the AST", etc. It’s all queries all the way down.

But there are also additional queries like: "What’s the type of the identifier in file X at cursor position Y". Such a query fires then another query that triggers the current file to be parsed into AST. With that you can fire another query that gets you the identifier at the cursor position. With that we can then fire off another query that resolves the identifier to its definition. If that turns out to be in another, we ask for that file to be parsed, etc.

The beauty of this architecture is that you don’t spend time processing completely unrelated files. You only process what is necessary to respond to a particular query. If a source file is completely unrelated to the running query it will never be processed.

Caches, caches and more caches

To speed things up even further, queries can easily be cached because they are expected to be pure. They should not have any side effects. This means that you can always re-execute a query and get back the exact same result. This property makes it perfect for caching too.

Queries can be automatically cached and when the cache consumes too much memory, you can just clear it. The next invocation of the query will see that there is no cache entry anymore and will simply re-run its logic and cache the results again. It might just run a little slower once until the result is cached again. But will never return an incorrect result.

But for the cache to be correct there is one crucial detail: It also needs to include the passed arg in the hashed cache key. This in turn means when Query A is called in many places with multiple different arguments passed to it, each argument will create a new instance of that query with its own cached return value.

Shape of a Query

A query is typically defined as function with two arguments

- Database

- Argument (sometimes confusingly also referred to as input)

Expressed in TypeScript it would look like this:

type Query<T, R> = (db: Database, arg: T) => R;

The db parameter is where all queries live on and The arg parameter is what you call the query with. To call a query inside a query you do db.call_other_query(someArg). To make this nicer and the database less of a thing to know about, most implementations add some sugar in the form of macros or decorators:

class MyDatabase extends Database { @query getTypeAtCursor(file: string, offset: number): Type { const id = this.getIdentifierAtCursor(file, offset); const type = this.getTypeFromId(id); return type; }}

Inputs: The source of truth

When a file changes on disk you want to somehow tell the compiler that it should invalidate it so that the cache entry is cleared and the next time a query asks for it, it re-processes that file. This is done through Inputs. An Input is a stateful object that can be written to. Usually they live on the database too.

watch(directory, ev => { if (ev.type === "change") { const content = readTextFile(ev.path); db.updateFile(name, content); }});

Reading inputs in queries usually involves calling a method or accessing a special property on it.

class MyDatabase extends Database { files = new Map<string, FileInput>() // Setter helper updateFile(name: string, content: string) { const input = this.files.get(name) ?? new Input<string>() input.write(content) this.files.set(name, input) } @query parseFile(file: string): AST | null { const fileInput = this.files.get(file) if (fileInput === null) return null; // Read input const code = fileInput.read() return parse(code) }}

To change or not to change

The key difference here compared to signals is that nothing really happens we have written to an input. Queries are not automatically re-executed or anything like that. Contrary to Signals in UI programming which are typically some form of "live" subscriptions, Queries are not live.

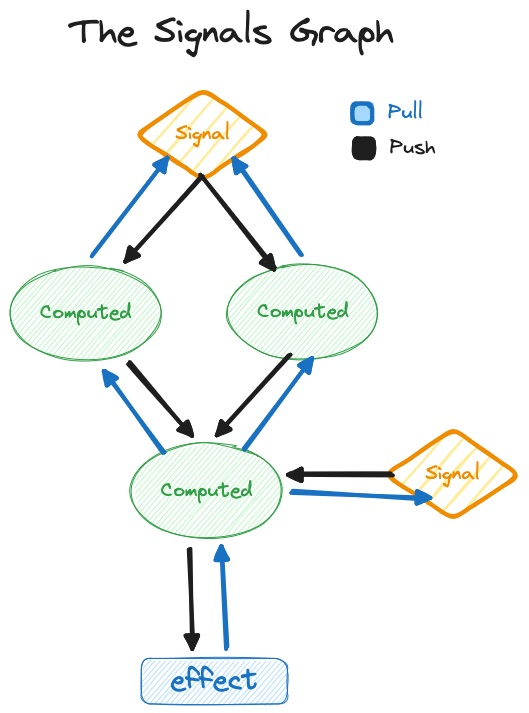

In a Signals system a change to a source signal marks it as dirty, and then it follows all active subscriptions and flags every derived/computed signal as dirty until it reaches the place where the subscription was triggered. The triggering part is typically called an Effect. Changes are sort of pushed through the system and when it reaches an effect, it re-runs and "pulls" the new values. There are of course various optimization strategies that libraries employ, but that’s out of scope for this article. What’s important to remember is that they are essentially a push-pull system when it comes to writes.

A push-pull architecture is perfect for UI rendering. Changes often need to be displayed instantly and you need to ensure that the whole screen is in sync. All signals rendered must always show the value of the same revision they were part of. The situation that the top half of the screen shows new values, whereas the bottom half still renders stale ones, should never occur. This is often referred to as a "glitch". Pushing changes through the system is an elegant way to ensure that this never happens. It basically trades more memory with faster execution and being able to guarantee a glitch-free result.

Query based compilers work differently, they are demand driven. You have to ask for them to be re-executed. It’s not as crucial that everything happens in the same tick. It’s totally okay for the query for autosuggestions to return and the query for type errors to return a few milliseconds later. There is no need to keep some sort of screen in sync per frame. Correctness must be ensured, of course. But the timing guarantees are a bit more relaxed.

Always pushing changes through the system is too expensive because a query based compiler will easily have >100k nodes depending on the project size. At that scale, memory becomes a real performance concern. To reduce the memory consumption, dependencies are only tracked in one direction in a query based system compared to tracking both directions with signals.

The secret sauce: Revisions

But still, like with Signals, correctness is a hard requirement for query based systems. So if queries finish at different times, how is it guaranteed that the results are always correct? The key insight is that ultimately queries are a pure function over their inputs. Given the same inputs, the same result must occur. The result is therefore correct.

Inside the system there is a global revision counter that is incremented with each changed input. Each node has a changed_at and verified_at field that can be used to check the status of the cached value.

interface Node<T> { changed_at: Revision; verified_at: Revision; value: T; dependencies: Node<any>[];}

This tells us whether we can re-use the cached results of a node or not. That said, due to only tracking dependencies in one direction we need to always dirty check all dependencies of a query up to the leaf nodes, unless verified_at is equal to the current revision which allows us to bail out early. When you reach a leaf node and realise that it hasn’t changed at all, despite the global revision counter being increased, you just set all verified_at properties of parent nodes to the current global revision. If the input or a query result has changed you update both the changed_at and verified_at fields. But when somewhere a query still returns the same result despite its dependencies having changed, we also bail out and only update only verified_at pointers while unwinding the stack.

What about threading?

This is one killer feature of query based systems. Depending on the programming language to compile, you can aggressively parallelize tasks like parsing files. If you guarantee that each query can only be executed by one thread at a time you can parallelize a lot of work. Since queries tend to be pretty granular you can often kill a thread and spawn it again with the latest revision. This is an aspect that I need to dive into deeper myself, but I find it interesting that restarting work is a possibility at all in such a system.

Which one is better?

It depends. Signals are better for UI rendering, but the query-based system is more appropriate for a compiler. It all depends on the use case. In either way I find it interesting that different systems sorta arrived at similar building blocks and concepts behind the scenes to achieve an incremental system.

I’m kinda wondering what our JavaScript tools would look like if they were built from the ground up to be incremental. What would something like vite look like if it was built as a query-based system? In spirit, a dev server is similar in that it is a living thing that we constantly query for data apart from HMR updates which are pushed from the server. Maybe a mix of both signals and a query architecture would be the golden ticket?