As a part of building AwaySync, an asynchronous communication product that is at an embarrassingly early stage of development, I’ve been doing a lot of research into collaborative editing.

Most open source collaborative editors use Yjs, a CRDT implementation that enables offline editing, awareness, and decentralization. I tried out Yjs with ProseMirror, a popular text editor and the base for businesses like TipTap, and ran into some interesting problems:

- To support offline editing, you should probably keep the Yjs document around forever. Now your backend has to store the Yjs doc as a binary blob as well as your editor’s s…

As a part of building AwaySync, an asynchronous communication product that is at an embarrassingly early stage of development, I’ve been doing a lot of research into collaborative editing.

Most open source collaborative editors use Yjs, a CRDT implementation that enables offline editing, awareness, and decentralization. I tried out Yjs with ProseMirror, a popular text editor and the base for businesses like TipTap, and ran into some interesting problems:

- To support offline editing, you should probably keep the Yjs document around forever. Now your backend has to store the Yjs doc as a binary blob as well as your editor’s source format (usually HTML/JSON). Which is authoritative?

- Yjs is kind of a black box, and since I was using Go I couldn’t create or introspect documents directly without dispatching to Node or Rust (I wrote a POC for this by the way)

- For production, almost everyone uses WebSockets and not WebRTC, both for performance and because WebRTC is a little broken between browsers. While many WebSocket servers for Yjs exist, using them with an authoritative backend and horizontally scaling them is no small task. My feeling at this point was something like “Yjs works really well, but using it without making it the core of your software is kind of a weird experience”.

You can probably tell at this point that I’m an overthinker.

I’ll also pause here and say that Yjs is a cool project and if you’re looking for something production-grade, you should use it! My gripes can mostly be addressed by using y-redis, load balancing to hocuspocus instances by document, or paying for TipTap Cloud.

Around this time I stumbled upon the blog post “Collaborative Text Editing without CRDTs or OT” by Matthew Weidner, which outlines a novel way to implement collaborative text editing from scratch:

- Assign a unique ID to every character in your text document

- Share operations on characters between clients (namely “insert after ID, delete ID”)

- Apply those operations literally without worrying too hard about state or correctness Even a dullard like me can understand this algorithm!

Feeling inspired, I decided to give DIY collaboration a try with Lexical, a text editor by the folks at Meta. This had the added bonus of giving me insight into a non-Prosemirror world even if things didn’t work out.

Adding UUIDs to Lexical

Lexical represents documents (EditorStates) as a tree of nodes. Nodes like paragraphs have children, and the lowest child in the tree is often a text node. Each node has a NodeKey, a random ID that is local to the client (browser tab) and is not exported when the document is persisted, which means they aren’t super usable outside of memory.

So I couldn’t use NodeKeys directly, but it was good to know there were some internal considerations in Lexical about uniquely tracking nodes. To identify nodes in a way that persisted to exports, I created a custom NodeState to ensure that every node had a UUID, and maintained a map of those UUIDs to NodeKeys in memory.

// Our custom NodeState

const syncIdState = createState("syncId", {

parse: (v) => (typeof v === "string" ? v : SYNC_ID_UNSET),

});

// A map of UUIDs to NodeKeys

const syncIdMap = new Map<string, NodeKey>();

...

// The following code runs in a mutation listener for "create" events

let syncId = $getState(node, syncIdState);

const mappedNode = syncIdMap.get(syncId);

// If node is brand new or a clone, give it a UUID.

if (

syncId === SYNC_ID_UNSET ||

(mappedNode && mappedNode.getKey() != node.getKey())

) {

syncId = uuidv7();

syncIdMap.set(syncId, node.getKey());

$setState(node.getWritable(), syncIdState, syncId);

}

The blog mentioned applying UUIDs to every character in a document. While this is the “most correct”, the performance and storage implications are likely insane, so I settled on assigning one to every word instead. To accomplish this I used a Node Transform that recursively splits text nodes by word, separated by unmergeable TextNodes for each space (“ “) character.

When paragraphs are pasted or typed, words are split into distinct TextNodes

This enables editors to collaborate on the same paragraph/sentence at the same time without conflict, unless they’re editing the same word (seems rare, or at least rude).

When paragraphs are pasted or typed, words are split into distinct TextNodes

This enables editors to collaborate on the same paragraph/sentence at the same time without conflict, unless they’re editing the same word (seems rare, or at least rude).

Streaming Mutations from Redis

Now onto the collaborating part. Lexical has a concept of mutations, which occur after a node has been created, destroyed, or updated. By registering a mutation listener we can wait for the user to modify a node, then send that mutation to other clients so they can replay it in their own EditorState. To assist with replaying, “create” messages include the previous node ID or parent node ID, so we know if the node needs to be inserted after a sibling or as the first child of a parent. This differs from Operational Transform (OT), which relies on relative character positions for create and delete operations.

Here’s what the TypeScript types look like for mutation messages shared between peers:

export interface SerializedSyncNode extends SerializedLexicalNode {

[NODE_STATE_KEY]: {

syncId: string;

};

}

export interface NodeMessageBase {

streamId?: string;

userId: string;

node: SerializedSyncNode;

previousId?: string;

parentId?: string;

}

export interface CreatedMessage extends NodeMessageBase {

type: "created";

}

export interface UpdatedMessage extends NodeMessageBase {

type: "updated";

previousNode: SerializedSyncNode;

}

export interface DestroyedMessage extends NodeMessageBase {

type: "destroyed";

}

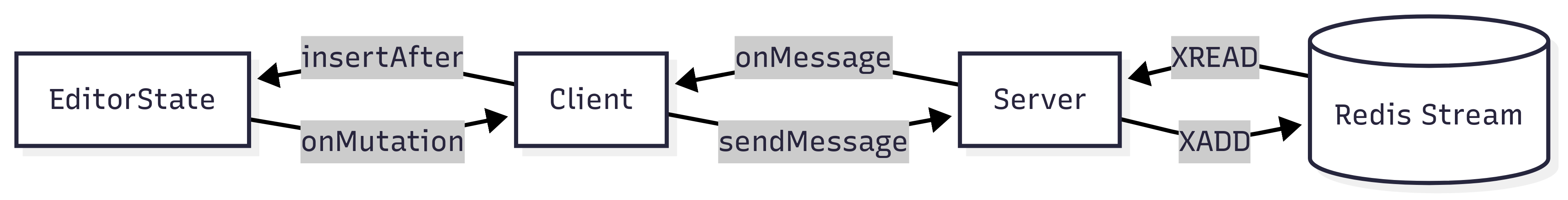

My initial idea for this was to use WebSockets to send the message to a centralized server, then have that server add it to a Redis Stream which all clients would poll for updates from. The server implementation can be quite dumb, as its only purpose is to consistently broadcast all mutations to all clients, which means you can run any number of servers without worrying about who has what in memory.

A diagram showing the flow of messages from Lexical into Redis

Redis Streams are an interesting bit of technology - they’re append-only data structures whose entries are uniquely indexed by a stream ID. This index allows clients to read from the stream from any arbitrary point in the past, assuming the stream hasn’t been garbage collected (trimmed). This pairs well with offline editing use cases, if an editor keeps track of the last stream ID they saw from the server, they can continue streaming when reconnecting and “catch up” to other editors who stayed online.

A diagram showing the flow of messages from Lexical into Redis

Redis Streams are an interesting bit of technology - they’re append-only data structures whose entries are uniquely indexed by a stream ID. This index allows clients to read from the stream from any arbitrary point in the past, assuming the stream hasn’t been garbage collected (trimmed). This pairs well with offline editing use cases, if an editor keeps track of the last stream ID they saw from the server, they can continue streaming when reconnecting and “catch up” to other editors who stayed online.

The example server implementation is very bare bones, mostly because a production server would need authorization and you’d probably want to optimize the Redis calls for performance. Specifically, I think it’ll be common for clients to be streaming from around the same point in time, so we could deduplicate XREAD calls, or batch XADD calls. Honestly I was kind of surprised that there wasn’t some industry standard wrapper on top of Redis Streams that does this for me already.

To recap, with WebSockets and streaming in place, clients wait for Lexical mutations to occur, send those mutation messages to the server, the server appends those to the stream, and then broadcasts them to all peers.

There is no concept of correctness or determinism in this implementation, for better or worse, so if a stream message can’t be re-applied the failure state is to just ignore and keep applying new messages. I started working on a rollback mechanism and server reconciliation but it was a bit complex so I tabled it for now (classic MVP stuff).

Supporting Cursors

The demo was working at this point, but not being able to see your peers made it feel a little less magical. To support text cursors, I decided to poll for local cursor changes then add a message to the stream that mimics Lexical’s RangeSelection, with any NodeKeys replaced with references to UUIDs. When clients want to display a cursor, they look up the local node associated with that UUID, the HTML element associated with that node, then use “document.createRange” to determine where to draw a bounding box (the selection, if any).

A demo showing that cursor movements are streamed to peers

Adding cursor movements into the stream was an interesting choice - it seems like a Redis Pub/sub would be more efficient as cursor messages don’t need to be applied historically, or in order, but I worked with what I already had built. Unlike Yjs’ Awareness, there’s no concept of presence, so cursors just stop rendering after a few seconds of inactivity.

A demo showing that cursor movements are streamed to peers

Adding cursor movements into the stream was an interesting choice - it seems like a Redis Pub/sub would be more efficient as cursor messages don’t need to be applied historically, or in order, but I worked with what I already had built. Unlike Yjs’ Awareness, there’s no concept of presence, so cursors just stop rendering after a few seconds of inactivity.

Undo and Redo

A common problem with collaborative text editors is undo and redo, since users usually expect undo to revert changes they’ve made, not changes remote editors have made. In my case I save each batch of mutations that we send to our peers onto a stack, then when the user requests an undo I pop off that stack and try to reverse each of their messages.

This required adding the previous node’s state into the messages (otherwise how do you “undo” a delete?), which means the stream gets a bit more data than is used. At one point I thought this might be usable for conflict resolution (ex: a peer deletes a node I was editing, we can compare what they thought the node content was at that time and restore the node), but didn’t end up doing anything interesting here.

Node Immutability

Matthew’s blog also mentions introducing an “isDeleted” flag to track whether or not a node is deleted without actually deleting it, which could make conflicts easier to handle. I started building this with a new NodeState but ran into a lot of UX problems, so decided not to include it in the demo. You can view my attempt at an “Immortal” TextNode here: https://github.com/mortenson/lexical-collab-stream/blob/main/src/Collab/ImmortalTextNode.ts

Persistence

Since our server doesn’t actually know anything about the EditorState, or really anything about Lexical at all, clients regularly persist their version of the EditorState to a normal key value store in Redis. This isn’t very performant, you are doing multiple writes of the same data again and again for each peer, but maybe that could be used to identify drift between clients. If two clients persist the same document with the same stream ID, but the document content differs, something went wrong. Again, I didn’t end up doing reconciliation for this MVP but there’s some path to it hiding in here…

Note: In Yjs, I think the normal way to do this is to have an authoritative server apply peer updates to a document in memory, then broadcast its own updates to all peers. Since we never apply the Redis Stream server-side, we can’t really do this (and realistically would probably generate a list of mutations for peers to apply anyway).

Last minute WebRTC support

Things were going well with the WebSocket server, but I wanted to host a demo of things working without running my own infrastructure. This led me to seek a WebRTC implementation, which I accomplished using a (new to me) project called Trystero. Trystero uses public signaling servers (so I don’t need to run one) and greatly improves the DX of joining rooms, encrypting data, and broadcasting messages to peers.

Since we don’t have Redis for centralization, each client in the WebRTC version stores their own version of the stream, and generates its own stream IDs for outbound messages. When a peer joins the room, all other peers blast it with their version of the EditorState so it can initialize itself. If a client disconnects and reconnects, other peers will try to catch it up by sending it a subset of its stream based on the reconnecting client’s last known stream ID.

This leads to more bugs and inconsistency than WebSockets, and is three times longer code-wise, but it being doable last minute gives me some hope about the implementation and I’m open to improving it if people are interested. For now however, consider it demoware.

Conclusion

Making collaborative editing work without a CRDT or OT implementation is doable even by novices such as myself, but is it worth it? I’d say yes, but I’m not using this in production and don’t think that it’s better in any way than Lexical’s Yjs integration, so take that with a grain of salt.

One thought I have coming out of this is that it’s not the end of the world to use something without consistency guarantees, especially at a small scale. CRDTs aren’t bug-free, and adopting them has some long term implications for your application.

I think you could re-implement what I did in this demo in a week or two, and use it with many existing frameworks and editors. It doesn’t really change how you store your documents long term (but keeping the latest stream ID next to the EditorState is nice), and Redis isn’t completely essential to its operation (although it enables horizontal scaling and lets you avoid WebRTC pains).

Simple doesn’t mean better, and you could argue this is pretty far from simple, but I enjoyed trying out Matthew’s idea and will definitely use Redis Streams in the future!

If you use Lexical and want to try it out there’s instructions in the README, or you can otherwise check out the demo (be patient, WebRTC is slow/jank at times).