Detail from Viennale 2025 poster.

Werner Herzog was once the codirector of the Viennale for a brief spell, from 1990 to 1992. After a budgetary crisis in 1989, the following edition had been canceled, and an ersatz Viennale called Novemberkino was held instead. In 1991, as the festival resumed, Herzog cast high-wire artist Philippe Petit into the air between the main festival cinema and an aquarium on opening night. Some had dismissed the German filmmaker’s appointment itself as a marketing stunt. But the theme of this Viennale was the magic of cinema, and Herzog wanted to draw a line through the skies for the occasion.

From aerial wires to heavy chains: Those who were at the Gartenbaukin…

Detail from Viennale 2025 poster.

Werner Herzog was once the codirector of the Viennale for a brief spell, from 1990 to 1992. After a budgetary crisis in 1989, the following edition had been canceled, and an ersatz Viennale called Novemberkino was held instead. In 1991, as the festival resumed, Herzog cast high-wire artist Philippe Petit into the air between the main festival cinema and an aquarium on opening night. Some had dismissed the German filmmaker’s appointment itself as a marketing stunt. But the theme of this Viennale was the magic of cinema, and Herzog wanted to draw a line through the skies for the occasion.

From aerial wires to heavy chains: Those who were at the Gartenbaukino on opening night last month watched an Iranian musician, Mona Matbou Riahi, ring in the Viennale with a slow walk to the stage, holding shackles in each hand, then dropping them to take up her clarinet. What was being communicated with those chains, clanging ominously into the darkness of the theater? If it clashed with how the Viennale spoke about itself in some ways, it chimed with others. In her opening speech, the festival director Eva Sangiorgi echoed the solemn effect of those shackles, and evinced a vague consciousness of global crisis. She expressed “a deep sense of disorientation” with the present moment before referring to the poster, on which a fox plays dead for an attacking bird. The image—from a thirteenth-century French edition of Physiologus, a proto-bestiary of moral tales—is editorialized on the Viennale website as an invitation to reconsider who is hunted and who is hunter, and Sangiorgi doubled down on that statement, despite online criticism. (“The roles are always blurred only for the perpetrators,” one commenter responded in German.) Sometimes, Sangiorgi mused, a hunt might turn into an encounter, “a reminder that what we expect may sometimes be only our own preconception.” It seemed a clumsy fable for the present moment, with ongoing genocidal wars and rising authoritarianism making quite clear who among us holds power, and who does not. There is a case to be made for ambiguity and non-didactic art in an age of blinkered certainty and official falsehoods, but it need not be quite so vague and knotty. The festival had chosen a particularly provocative way to be uncommitted, and whatever one thought of it, a couple of things were certain: Herzogian wonder was muted, and the spectacular levity of the ’90s had vanished altogether.

Then Christian Petzold took the stage, having been appointed Viennale president this spring. When I asked festival workers and frequenters what this might mean, Petzold for President, the general consensus was that the position was “symbolic.” One observer referred to the tenure of Herzog, using the phrase “marketing stunt,” conceding it was a good idea in light of Austria’s high rate of inflation. (Popular German directors for hard times?) In extolling the pleasures of cinema, rather than its ethics, Petzold aligned himself less with Sangiorgi than with Herzog. On first attending the Viennale back in 2000, Petzold said, he had been reading the autobiography of Jean Renoir, alighting on a little parable in which two carpenters cross paths. While one is American and the other is French, these men do not talk about nations. (They do not play with role reversal like the Viennale fox and bird, either.) They talk about wood, technique—and have fun doing so. This is what film festivals could be like, Petzold ventured: talking about cinema, talking about wood.

When I first attended the Viennale, in 2023, I had been reading Thomas Bernhard’s Woodcutters. I didn’t know how excoriating Bernhard’s narrator would be about the cultural scene of 1980s Vienna, seething in his oft-mentioned wing-back chair for the duration of the book. It risked putting me in an ungenerous state of mind for what most cinephiles regard as “some kind of paradise,”1 but as a prelude to a scheduled workshop with Pedro Costa for beginner critics at the InterContinental Hotel, it was perfect. I couldn’t quite believe it when Costa lamented the state of film culture for two straight hours while sitting in a wing-back chair. As for his complaints, implied amid disappointed pauses: Why were we having these conversations in an institutional setting? Why weren’t we drinking and rambling in a thick fug of smoke, well into the night? (We were, but he didn’t ask.) It just wasn’t like this when *Cahiers *critics used to descend on Lisbon back in the ’70s. Costa might soon go full Bernhard, I thought, sitting in my unremarkable chair. Costa was suffering through the professionalization of film culture as Bernhard’s narrator suffers through “an artistic dinner” and starts to dream of “the forest, the virgin forest,” and the secluded life of a woodcutter. Costa, sitting in the wing-back chair, looking leonine and formidable, gestured around the airless room, took his handsome jaw in his hand, and shook his head. Was he dreaming of woodcutting too?

*Awakening *(Joanna Hogg, 2025).

The Viennale was not always called the Viennale. It began in 1960 as the “International Festival of the Most Interesting Films of the Year 1959.” That collaboration between Vienna’s Stadtkino, an arthouse cinema, and the Association of Austrian Film Journalists lasted one edition, and then received a city subsidy in 1962, when the mayor restyled the film festival with its far catchier name. Unlike European festivals with origins in the interwar years (Venice in 1932, Cannes in 1939), the Viennale was not established in the state’s interests. It was founded neither to export an ideology nor to bolster an industry, but simply because critics—a few real cinephiles!—wanted to see films that had not yet reached Austrian screens.

Maybe that first edition had been very woody: Renoir, Cahiers, real film chat only. Yet it did not take long for international talk to take hold. While the festival tried to be lighthearted, calling itself a “Festival of Gaiety” in the ’60s and celebrating comedies, the inclusion of Eastern European films (even in less prominent slots) resulted in accusations of pro-Communist sentiment. Then the revolutions of 1968 erupted. Otto Wladika, the festival director at that time, introduced post-screening discussions, accommodating the turn toward political expression from politicized publics. Talking about nations was now on the table.

If Petzold’s opening comment resonated with the earliest iteration of the Viennale—pure cinematic appreciation, with national difference set to one side—then the festival trailer, Joanna Hogg’s *Awakening *(2025), echoed post-’68 anxieties. *Awakening *begins with the filmmaker in bed. She is bothered by offscreen noise: aircrafts, sirens, and riots. She tries to block it out, head beneath pillow, and fidgets in irritation, before moving from bed to window and opening up the shutters, looking outside. We do not see the source of the strident cacophony; the final image vivifies from black-and-white to color and focuses on Hogg’s “awakening,” a close-up of her eye. It’s not much more subtle than shackles, and was similarly absent of specificity. Where was Hogg? When? What unrest flared outside her terrazzo-tiled apartment? Was this an artist urging us to talk about the world? Perhaps I longed, after all, for one who wanted to talk about wood.

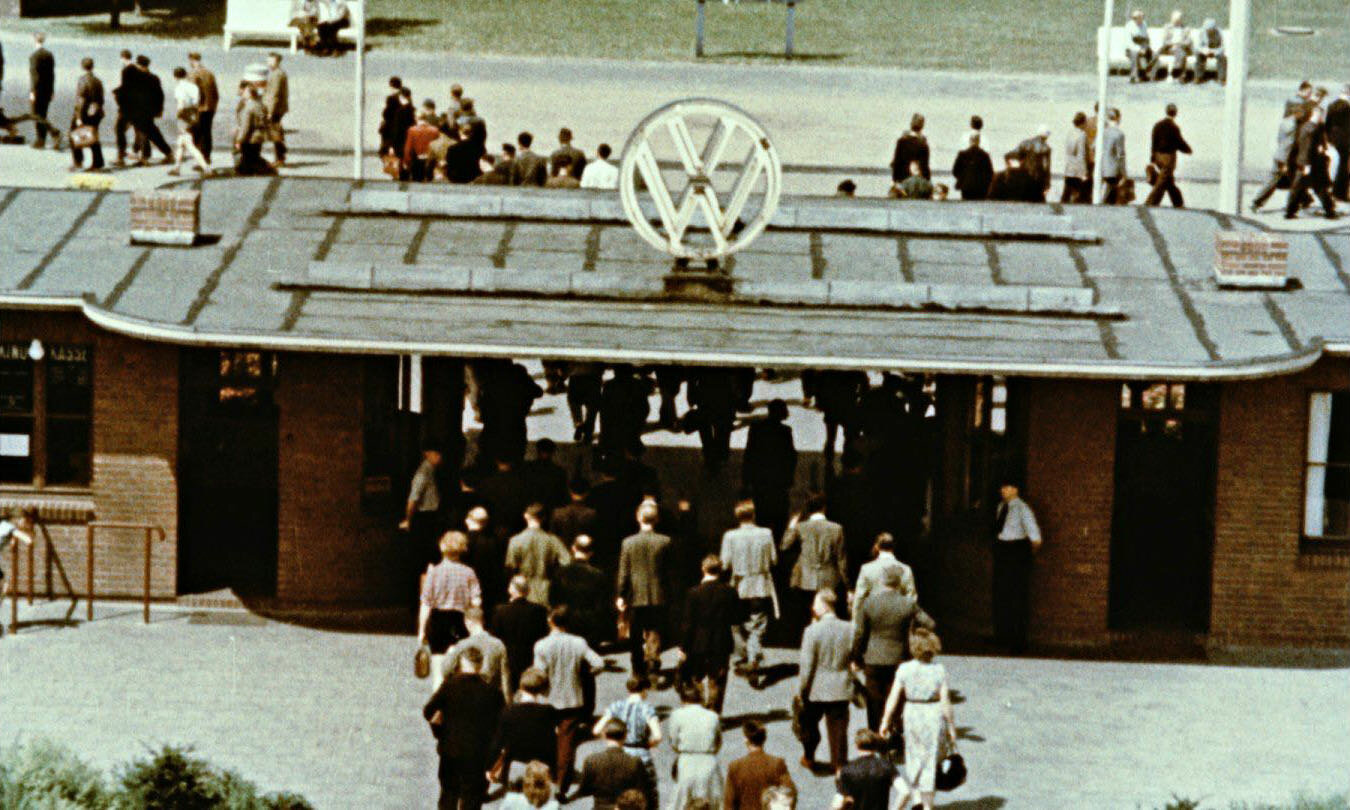

*The VW Complex *(Hartmut Bitomsky, 1989).

Most filmmakers in attendance at the festival spoke with nuance about cinema, filmmaking methods, and their global contexts. Petzold himself soon forgot his binarizing call for wood, not nations, introducing a film he programmed with jokes about what the German Green Party was like in the late ’80s. (Even in translation, I did not understand them; these were for the home fans.) Hartmut Bitomsky’s ***The VW Complex ***(1989) whirrs with numerous process shots of machines shaping, painting, and assembling sheet metal, as Bitomsky’s voiceover continually solders raw materials to national history, Volkswagen to Nazi Germany, cars to arms. At another screening, Tang Shu Shuen answered an audience question about the unusual superimposition and montage in her period melodrama ***The Arch ***(1968), and ended up talking about American Flower Power. Les Blank had been involved in that peace movement when he edited this film, and infused an artful representation of Ming Dynasty China with unlikely Californian drops of psychedelia. Anyone who arrived late to Masao Adachi’s ***Escape ***(2025), a biopic of the anarchist terrorist Satoshi Kirishima, could have mistaken it for narrating the humble life of a construction worker in Japan who indulges in red wine and dad rock to help pass the time, yet revolution rattles in the nuts and bolts of this film as well. Adachi, who has previously advocated a fukeiron, or “landscape theory” approach, has more recently said that he thinks the politics of landscape filmmaking are exhausted, and his 4:3 frame here represents a tightening of his aperture. Even so, whether cutting film, metal, or wood, not one of these three works was cut off from the wider world.

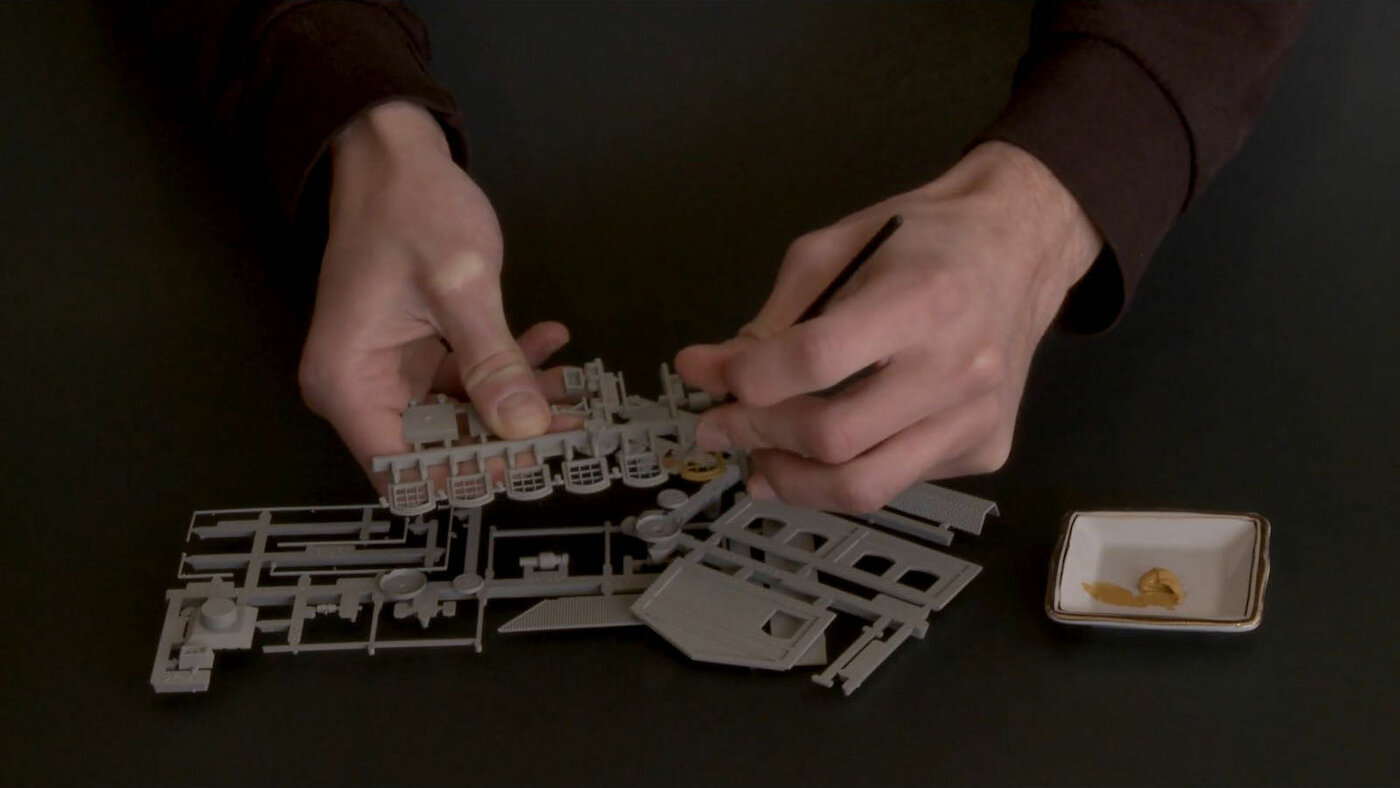

*little boy *(James Benning, 2025).

James Benning might seem to withdraw from filming the United States in ***little boy ***(2025): forgoing landscape, taking as his background black-box nowhere, adopting the worldview of a child making model structures and listening to the radio. The center of the film is divided into eight parts, which are framed in identically composed static shots and dated in chronological order from 1961 to 2016. Within each of those parts are two sections. First, an anonymous pair of hands paint the flat, colorless components of the given model in blue, green, yellow, or brown. Then the image cuts to the finished model—miniature building, industrial structure, or railroad—and political speeches replace popular songs on the soundtrack. While the image toys with solitary innocence, the sound links what we see to America and the world.

Dwight Eisenhower calls for peace in 1961. As governor of Alabama, George Wallace agitates for segregation in 1963. When Stokely Carmichael speaks to students in 1966, he speaks of Black Power. When César Chávez speaks to an audience in 1984, he speaks of migrant workers’ rights. Ronald Reagan acknowledges Iran received American arms in exchange for the release of American hostages in 1986. Then Severn Cullis-Suzuki, just an adolescent, silences world leaders in 1992 with an environmentalist speech at the UN Earth Summit. Then Hillary Clinton defends the continued American military presence in Iraq in 2010. Finally, Helen Caldicott exhorts an audience in 2016 to put an end to nuclear armament. No one is explicitly framed as good or bad, hunter or hunted. Benning does not ask that we reconsider our biases about US government officials or progressive activists. He just opens up that small scene, concentrated on model-making, and sets this back-and-forth in motion.

Benning described *little boy *as an intimate, personal work after the Viennale screening, one he had made while reading decades’ worth of his diaries. But it transcends the filmmaker’s own nostalgia and what might, in a less charitable reading, be taken as a boomer lament. Depending on prior knowledge and preconceptions about defense spending, racial politics, unionized labor, American intervention in the Middle East, and climate emergency, not to mention musical taste, *little boy *can be an emotional film with resonance that goes beyond Benning.

With Cullis-Suzuki’s urgent plea for adults to “stop breaking the world” imbricated among it, the sequence of Sinéad O’Connor’s “Molly Malone,” Cat Power’s “The Greatest,” and Tracy Chapman’s all-timer “Fast Car” had me in tears. That successive pairs of hands, nominally tethered to some “little boy,” kept painting and assembling models, as if naïve to struggle and destruction, was somehow devastating too. Look extremely closely, and you’ll find that Benning has affixed the logos of arms manufacturers to certain models, thus situating them within corporate America. With the final image, Benning puts the US military-industrial complex center-screen; an exact model of the “Little Boy” bomb that obliterated Hiroshima in August 1945 destroys the innocence of that “little boy” in the lowercase title. Watch the film back, and the seemingly benign rock ’n’ roll track that gets 1961 going, “It’s Late,” might now have too-late, apocalyptic connotations; the model dinosaur skeleton that precedes it, a warning of where we might end up.

It occurred to Benning in the post-screening discussion that he had made something simple, but sophisticated. It’s true. That tessellation of different elements follows an uncomplicated, coherent pattern, not difficult to learn, but little boy, all the same, exceeds the sum of its parts. That tension between withdrawal from the world and the vociferous persistence of international politics was, furthermore, striking in the film festival context.

*Escape *(Masao Adachi, 2025).

Some want virgin forests from film festivals, waxing romantic about some ideal cinephile past in which the sequestered black box of cinema kept politics and economics out. Others feel an obligation, whether ethical or calculated, to make an appeal to the current world in crisis and for the continued relevance of cinema. At the Viennale, the most impressive films turned toward a desire for worldlessness, the perspective of the individual, and the pleasure of making something small and discrete, while understanding it impossible to escape from the world completely. That Toso, the Japanese title of Adachi’s film, can be translated as both “escape” and “fight” struck me as appropriate. Even in relative wilderness, for both Adachi and Benning, there is no giving up the fight.

- Christoph Huber, “Status Quo and Beyond: The Viennale, a Success Story” in On Film Festivals, ed. Richard Porton (Wallflower, 2009), 131. Huber, an Austrian Film Museum curator and critic, is as baffled by the “effusive praise” from international visitors as he is by the “damning frustration” of locals. ↩