Mayan Calendar. Credit: Shutterstock | The Daily Galaxy –Great Discoveries Channel

A 13th-century manuscript sits under glass, its bark-paper pages filled with vivid glyphs and cryptic figures, in a quiet reading room in Dresden, Germany. Known as the Dresden Codex, it’s one of the few surviving Maya books, long admired for its enigmatic beauty and astronomical data. But new research suggests this ancient document holds far more than symbolic art—it contains a highly sophisticated mathematical framework, capable of tracking solar eclipses with remarkable precision.

For decades, scholars believed the codex’s eclipse tables were primarily ritualistic. …

Mayan Calendar. Credit: Shutterstock | The Daily Galaxy –Great Discoveries Channel

A 13th-century manuscript sits under glass, its bark-paper pages filled with vivid glyphs and cryptic figures, in a quiet reading room in Dresden, Germany. Known as the Dresden Codex, it’s one of the few surviving Maya books, long admired for its enigmatic beauty and astronomical data. But new research suggests this ancient document holds far more than symbolic art—it contains a highly sophisticated mathematical framework, capable of tracking solar eclipses with remarkable precision.

For decades, scholars believed the codex’s eclipse tables were primarily ritualistic. Now, researchers argue that these were not merely tools of divination or myth, but the output of an advanced calendrical system that, through layered cycles and subtle corrections, could project solar eclipses centuries into the future. The findings, published inScience Advances, suggest that Maya scribes were not just skywatchers but deep thinkers—mathematicians working within a model as elegant as it was accurate.

Sample Of A Page From The Dresden Codex And Its Hieroglyphs

The Maya civilization, which flourished across southern Mexico and Central America between 250 and 900 AD, has long been credited with developing one of the most complex calendar systems in the ancient world. But this new analysis shifts the focus from admiration to astonishment. By aligning lunar and ritual cycles into an overlapping framework, they achieved a predictive system rivaling those of pre-telescope Europe.

A Calendar of Convergence, Not Coincidence

At the heart of the study lies the Tzolk’in, a 260-day ritual calendar, and a lunar cycle system meticulously documented in the Dresden Codex. These two systems, researchers found, weren’t used in isolation. Instead, they were superimposed in a way that generated “interference patterns”—periods where solar eclipses were more likely to occur.

This alignment wasn’t accidental. According to lead author John Justeson, professor emeritus at SUNY Albany, the Maya recognized that by syncing the two calendars, eclipse events naturally surfaced at consistent intervals. “They weren’t just watching the skies,” Justeson told The Atlantic. “They were engineering time.”

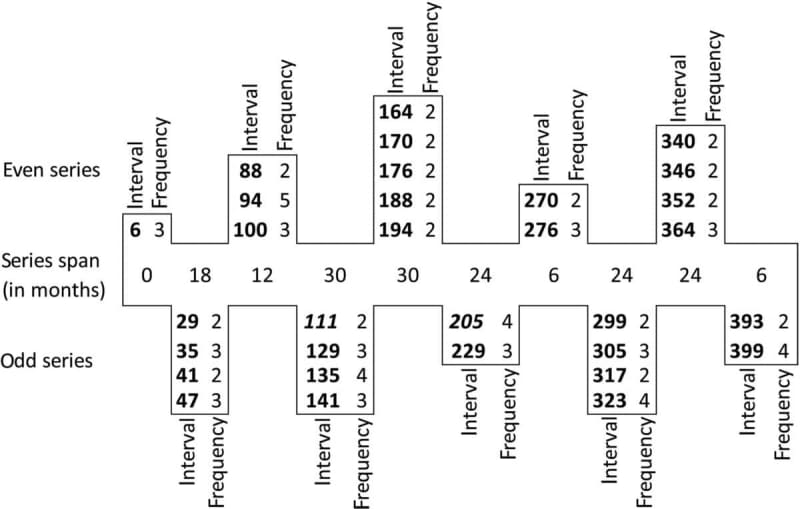

Frequency Distribution Of Repeated Intereclipse Intervals Among The First 3 × 405 Months In The Mayan Territory, 356 To 454 Ce

These overlapping calendars created what modern scientists would call a modular arithmetic system—mathematical structures that emerge when repeating cycles intersect. In this case, the 260-day ritual cycle and an eclipse-relevant lunar cycle of roughly 177 days created nodes—moments of convergence—that coincided with historical eclipse events. When extended across centuries and calibrated through successive corrections, the result was a predictive system of startling accuracy.

Long-Range Forecasting, Ancient Style

Rather than use a single fixed cycle, the codex features multiple eclipse tables that stack together. This layered method allowed for gradual correction, accommodating the drift that naturally occurs in any astronomical prediction model. The Maya method resembles techniques used in contemporary long-range forecasting—incremental updates based on cumulative error correction.

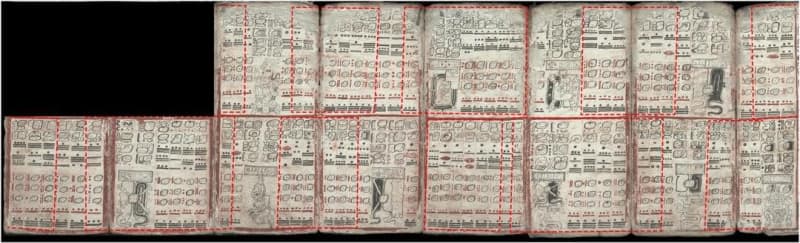

In Red, The Tables Corresponding To Solar Eclipses In The Codex

That’s what makes the tables so effective: they anticipate change. Over hundreds of years, the model remains reliable not because it is perfect, but because it is designed to evolve.

“These tables weren’t static,” explains Barbara Tedlock, an anthropologist and expert on Maya timekeeping at the University at Buffalo. “They were self-correcting. That’s not just empirical astronomy—it’s an adaptive system.”

The scale of the achievement is even more impressive considering the tools available at the time. With no telescopes, no written numerals as we know them, and no known abstract algebra, Maya scribes nevertheless managed to embed a working astronomical model inside a spiritual manuscript, written in pictographic script on painted bark.

Sacred Science on Bark and Ink

The Dresden Codex has long been viewed as a ceremonial artifact, preserved through conquest and colonization almost by accident. Written between the 13th and 14th centuries, it likely preserves knowledge developed during the Classic Maya period, centuries earlier. It contains 39 pages folded accordion-style, densely packed with glyphs and color illustrations—pages once dismissed as decorative or mythological.

This study reframes those assumptions. The codex is now interpreted as a hybrid document: part religious guide, part scientific almanac. Its pages serve both a cosmological and a computational function—offering rituals for divine timing while encoding long-term celestial patterns.

The researchers’ reinterpretation not only elevates Maya scientific reasoning, but challenges modern narratives about the evolution of astronomy. It suggests thatadvanced astronomical modeling doesn’t depend on Western mathematics or Greek rationalism—it can emerge from a completely different knowledge system, one grounded in ritual, observation, and symbolic structure.

This isn’t the first time scholars have pointed to the astronomical depth of ancient American civilizations. *The Venus tables *found in the same codex, which have long fascinated researchers, also reflect an advanced understanding of planetary motion, as shown in prior work by anthropologists and mathematicians.

Enjoyed this article? Subscribe to our free newsletter for engaging stories, exclusive content, and the latest news.