This is second and final part of the story of how my career as a software developer unfolded (part 1 is here). In this half I work at four different companies in the Seattle area, make my mark, and then retire.

Cavedog/Humongous Entertainment – 1997 to 2002

In 1997 my wife and I got annoyed with being so far from family (we were in Wisconsin, they were mostly in British Columbia) and we wanted to move to the west coast. This time I did a proper job search, talking to at least four companies in Vancouver and greater Seattle. I mostly interview pretty well and that is an important skill. A good job hunt requires a well written resume that reflects some actual achievements, the ability to inter…

This is second and final part of the story of how my career as a software developer unfolded (part 1 is here). In this half I work at four different companies in the Seattle area, make my mark, and then retire.

Cavedog/Humongous Entertainment – 1997 to 2002

In 1997 my wife and I got annoyed with being so far from family (we were in Wisconsin, they were mostly in British Columbia) and we wanted to move to the west coast. This time I did a proper job search, talking to at least four companies in Vancouver and greater Seattle. I mostly interview pretty well and that is an important skill. A good job hunt requires a well written resume that reflects some actual achievements, the ability to interview well, and ideally some contacts. This time, as with ASDG and as with every future job, contacts were a critical part of getting the job.

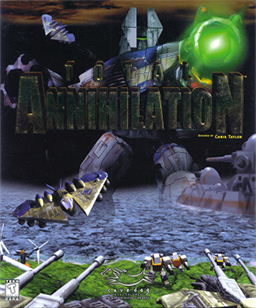

I got hired at Cavedog Entertainment with an unclear mandate or title based significantly on the recommendation of Chris Taylor who I had worked with back in the Distinctive Software days. I showed up as they were shipping Total Annihilation (TA) and they were having some stability problems. I wasn’t sure what I was doing but I eventually contributed by adding a crash reporting system that also included the ability for the game to ingest the crash reports to set up the stack and registers inside itself, like a bizarre crash-dump loading system. I do like that my crash system was purely text based – I could reconstruct crash states from text-only emails.

I got hired at Cavedog Entertainment with an unclear mandate or title based significantly on the recommendation of Chris Taylor who I had worked with back in the Distinctive Software days. I showed up as they were shipping Total Annihilation (TA) and they were having some stability problems. I wasn’t sure what I was doing but I eventually contributed by adding a crash reporting system that also included the ability for the game to ingest the crash reports to set up the stack and registers inside itself, like a bizarre crash-dump loading system. I do like that my crash system was purely text based – I could reconstruct crash states from text-only emails.

If a crash dump was passed to TA on the command line then TA would parse it, load the stack and registers from the text file into itself, then hit a breakpoint. After single-stepping past the breakpoint and a ret instruction the debugger would then display the state of the crashed program – call stack and all.

I also created an allocator that would keep individual memory allocations on different pages in order to expose out-of-bounds and use-after-free bugs. I “invented” these debugging concepts, with the quotation marks because I’m not sure when Windows integrated crash dumps, Dr. Watson, and pageheap – the same concepts but productized much better.

Some of the crashes ended up being caused by a buggy sound driver that was corrupting FP registers and by faulty memory on one of our test machines – sometimes it really is somebody else’s fault.

A combination of stress-testing TA locally and analyzing remote crashes in the debugger eventually helped me bring the crash rate down and it was at this job that I started making a career primarily out of fixing code rather than writing it. When programs were crashing, misbehaving, or running slowly I would often be the one asked to investigate and fix the problems, and I was good at this. I gradually lost the ability to create significant new features in consumer products

My next career mistake was sticking around too long at Cavedog/Humongous Entertainment, as the companies sunk into bankruptcy. Companies aren’t loyal to employees but they try to encourage employees to be loyal to them, to reduce attrition and depress compensation. It took me a long time to learn this cynical lesson, and I was too loyal to this sinking ship.

My next career mistake was sticking around too long at Cavedog/Humongous Entertainment, as the companies sunk into bankruptcy. Companies aren’t loyal to employees but they try to encourage employees to be loyal to them, to reduce attrition and depress compensation. It took me a long time to learn this cynical lesson, and I was too loyal to this sinking ship.

When leaving Cavedog/Humongous Entertainment I interviewed at Valve and Microsoft (using personal contacts for the Microsoft job in particular). I withdrew my Valve application before finding out if I’d get an offer and I do sometimes wonder what would have happened if I’d gone there nine years earlier than I actually did. I think I would have missed out on some valuable learning at Microsoft, but I might have become fabulously wealthy. There’s no way to know.

Microsoft – 2002 to 2011

At Microsoft I started in the Xbox group. My job was to help game developers create better games for their console. This involved writing samples and whitepapers, giving talks, visiting developers, and reviewing code, crashes, and performance analysis. I got to contribute to many dozens of games, honing my skills at optimizing and debugging.

At Microsoft I started in the Xbox group. My job was to help game developers create better games for their console. This involved writing samples and whitepapers, giving talks, visiting developers, and reviewing code, crashes, and performance analysis. I got to contribute to many dozens of games, honing my skills at optimizing and debugging.

Giving these talks for Microsoft plus teaching at DigiPen took me from being pathologically afraid of public speaking to absolutely loving it.

One of my most memorable contributions was Halo 2. I didn’t contribute much to the game. Maybe only one commit. And that was a one-line fix. But that one-line change was enough to make the game run about 7% faster!

When the Xbox 360 was being created I voraciously devoured the CPU manual. I wasn’t assigned the job of CPU expert, I just became the CPU expert and shared my distilled knowledge with my coworkers and other game developers. I gave talks and created CPU pipeline animations to help developers understand this bizarrely finicky CPU.

Reading the CPU documentation multiple times eventually gave me a powerful intuition for how the undocumented details of the CPU must work, and this is what allowed me to find a CPU Design Bug in the Xbox 360 CPU. I discovered – with just weeks to spare – that the xdcbt instruction was so dangerous that having it anywhere in an executable could cause memory corruption, even if it was never executed. You can’t make this stuff up.

The Xbox 360 project was in trouble – it nearly didn’t get finished in time – and the leads were willing to accept any help that was offered. This is how I ended up working on some fascinating aspects of the project:

- I realized that 4-KB memory pages were dramatically harming performance. That realization led the kernel developers to use 64-KB pages for all code, and I then modified the Windows-based heap (basically orphaned code that nobody understood) to use 64-KB pages

- I noticed that the CRT math functions (sin, cos, exp, log, etc.) were poorly written for our quirky CPU. I rewrote these functions to make them about five times faster. The faster versions gave bit-identical results, except in the cases where I fixed some correctness bugs. Apparently the original developers were slightly confused about how denormals work

- I created a hacky tool that would single-step the CPU for an entire game frame and record the instructions executed. I then wrote a tool that would replay these execution traces and look for patterns that would trigger CPU pipeline flushes or other slowdowns. Load-hit-stores, reads from uncacheable memory or 4-KB pages, floating-point comparison branches, and much more

- I also created a tool (Pgo-Lite) that would use these execution traces to rearrange code for better i-cache efficiency. This simple step made most games run about 7% faster in the Xbox 360’s two-way i-cache (make functions that call each other adjacent – that’s it)

Presumably the IBM employees who had designed the Xbox 360 CPU understood how it worked better than anybody else in the world, but they didn’t necessarily understand the implications of how it worked. It turned out that prefetch instructions which missed in the TLB cache were discarded, which is what made 4-KB memory pages uselessly slow. And it turned out that speculative execution of extended-prefetch instructions was the same as real execution (the CPU design bug). I was in the right place – the intersection of CPU internals knowledge and in-the-trenches experience – to realize these two critical implications.

I was sometimes amazed that I was left alone to pursue these madcap projects but at that time at Xbox it was results that mattered. Not only did they let me ship all of these diverse projects, they gave me an excellent review (a coveted 5.0 rating) and let me transfer to London for a year.

It is worth pointing out, however, that while I got a nice bonus and more stocks than normal after that year it was actually not spectacular compensation for helping save a multi-billion dollar project. Compensation at Microsoft is determined more than anything by level and at level 64 (or whatever I was) the biggest bonuses they will give you don’t match “meets expectations” for a level or two above. Just as when playing video games, leveling up is everything. I got a couple of promotions on the back of my Xbox 360 work but in hindsight I realize that I was falling behind.

Aside: one day while unicycling to my job at Microsoft (I was training) I saw a limo pulling in. I rode over to see who was in it and it was Don Mattrick and some other people from my Distinctive Software days. We chatted and I rode away thinking about how little we had all changed. They still loved expensive cars and the trappings of power, and I loved odd commute methods. They have more money. I like to think that I have more fun.

I eventually got bored of the Xbox 360 and moved to the Windows group to focus on performance investigations. It was here that I first learned about Event Tracing for Windows (ETW). ETW allows a wealth of performance information to be recorded on consumer Windows machines.

I saw the value in recording performance traces on customer machines when they were encountering issues, and I learned the dark art of how to analyze these traces. This was the most useful skill that I had learned in years. The majority of my blog posts – including the ones that cemented my reputation – would not exist if I hadn’t learned these tools. Suddenly I had the magical ability to understand performance issues that only ever occurred on remote machines. I took this skill to subsequent jobs and it – plus debugging obscure crashes – became the main way that I contributed.

When working with ETW I became acutely aware that while a profiler can tell you how long different parts of a program take, that information is useless without knowing how long these different parts should take. Although the cycle-accurate estimates of the 68000 were long gone it is often still possible to guess when an algorithm has gone quadratic, or when a function is either “too” expensive or called “too” often. Knowing this for your own code is vital. Guessing this for code I’d never even seen the source code for was often my secret sauce.

But, the excessive structure at Microsoft became frustrating. I created a one-line fix that would sometimes make Internet Explorer’s frame rate increase by 10x or more, but landing this trivial change required enduring interminable bogus security reviews. Meanwhile the code analysis team kept filing bugs and wasting developer time without acknowledging that the “bugs” were actually highly speculative. I was chafing at the amount of process and I wanted more freedom.

Valve – 2011 to 2014

My next job was working at Valve Software (based on personal recommendations from several Microsoft people who had moved there). In many ways this job was perfect for me. With no management structure I had the freedom to work on what I saw as valuable. And, Valve’s games were loaded with low-hanging fruit. There was no shortage of quadratic algorithms, obsolete throttling, logic errors, crashes, and memory leaks. I fixed bugs at a higher rate than I had ever managed before, and these were important bugs that were costing money and wasting the time of both developers and players.

One logic bug that VC++’s /analyze found led to one of the L4D2 designers saying “so that’s why we couldn’t tune the difficulty of that one level…” – it was years too late to fix it

I used Visual C++’s /analyze feature to find thousands of code correctness bugs, often in rarely executed code. In one memorable case I found an sprintf statement that was guaranteed to crash if executed. I created a CL to fix this bug on Friday, planning to submit it on Monday. On Sunday there was a power outage at Valve’s data-center servers. While the servers were being brought up many rarely executed code paths were hit, including this one. Steam crashed every time they tried to restart it. Steam remained down for several hours while the bug was investigated and fixed and Steam was recompiled and deployed. If I had found this bug just a few days earlier then Steam would have restarted after this power outage without difficulty. If you couldn’t play games that Sunday morning in 2014 now you know why.

I also fixed or created a lot of processes while at Valve. I worked on the build system and set up source indexing and symbol servers. I even figured out how to do the equivalent of symbol servers on Linux, and wrote some Linux debugger extensions for source indexing. Being able to load a crash dump on Linux and have symbols and source magically appear (just like on Windows!) was pretty amazing.

I also ran into some serious dysfunction at Valve. I filed an HR complaint about bullying by one of my coworkers (name withheld). I found that there were already three outstanding complaints against this person – including one from the director of HR. Years later all the complainants have left and the “brilliant jerk” remains.

On the other hand, the yearly company trips to Hawaii were definitely a lovely bonus.

One of my favourite investigations was when I was asked to look at memory consumption on CounterStrike servers. I found an unused global variable that was consuming 50 MB of memory per server process, and I found map ID mismatches that were wasting 20 MB every time a new game started. Those two fixes saved a huge amount of memory and greatly increased the number of server processes that could run per machine. Success.

But while I was on the live servers doing investigations I decided to look into some server processes that were consuming a lot of CPU time. They were consuming all of one core. I fired up perf and found that they were spinning in an eleven instruction loop. Forever. At first I assumed I was misunderstanding the data. I was new to perf and me being wrong was the most likely explanation for what seemed like impossible behaviour.

It turns out that there was a pathfinding bug. Every now and then the pathfinding algorithm would generate a set of nodes that created a loop and the game would traverse it forever. Player connections would time out and the server would keep spinning – wasting CPU time for no reason. Over time more and more server processes would hit this trap and the percentage of server CPU time going to this one loop would increase. The only reason this had never been noticed is that every month the server machines would be rebooted. The CPU usage graphs were hilarious with the daily usage variations overlaid on the inexorable climb caused by this bug.

It turns out that there was a pathfinding bug. Every now and then the pathfinding algorithm would generate a set of nodes that created a loop and the game would traverse it forever. Player connections would time out and the server would keep spinning – wasting CPU time for no reason. Over time more and more server processes would hit this trap and the percentage of server CPU time going to this one loop would increase. The only reason this had never been noticed is that every month the server machines would be rebooted. The CPU usage graphs were hilarious with the daily usage variations overlaid on the inexorable climb caused by this bug.

After fixing this series of bugs and thereby increasing CounterStrike server capacity by more than anyone had dreamed possible, I got another mediocre review. I’d been doing the best work of my career and Valve didn’t care. You can’t make a company value you so my only option was to leave.

Blogging – 2009 to present

While at Valve I started finding interesting issues that I felt compelled to share – and was allowed to share – so I started publishing more frequently on my blog. It started out being some pretty dry explanations of VC++’s /analyze, but I started branching out. A whole series on floating-point, advice on 64-bit porting, symbol servers, Linux, etc.

My first investigative reporting post was this one from 2011, and dozens more of this type followed. These were the ones that got the most readers, and got me noticed. But more importantly they were the ones that I most enjoyed writing. I found great joy in leading my readers through the twists and turns of solving an elaborate mystery, trying to explain the intricate details of quadratic algorithms, lock contention, and zombie processes.

It was also satisfying when one of my posts reached a large audience. It was extremely satisfying whenever one crossed 100,000 views, and some of them received many more views in Russian and other translations.

This blog was incredibly valuable during the job search that landed me at Google. And it was also surprisingly valuable within Google because often my manager and my peers would know about what I was doing because they read it on my blog. It was a brilliant form of self promotion.

But these aren’t the reasons I wrote the blog, and given how long it took to reap these benefits (my initial audience was basically zero) it would have been challenging to maintain motivation for these reasons. Instead I wrote because I wanted to. I had knowledge and opinions that I wanted to share with the world – that I needed to share with the world – and it felt good to get this out of my system.

I was reminded of this motivation when talking to my father. He loves music but he loves it in an esoteric way. When he tries describing it to “normal” people their eyes often glaze over, and so he has an unresolved need to share his passion. My work also has the problem that if I try explaining it at a dinner party in any detail then I will not be invited back. The blog gives me an audience of the small set of people around the world who do think my work is interesting, so that when I am at a social gathering I can talk about more interesting topics like long-distance unicycling.

Google – 2014 to 2024

This time I did my best job search ever. I talked to about twenty coworkers and ex-coworkers. I asked them for details about their compensation and most of them shared. For the first time I learned how much money was potentially available, and I wanted some of it. I hadn’t been paid badly in the past, but it was clear to me that there was the potential to be paid better. All else being equal, I wanted that.

I ended up talking to about ten companies (having ex-coworkers at the companies submit my resume) and doing formal interview loops with Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, and Google. I interviewed well and got offers from all four. My blog had had some “hits” at this point and I’m sure my increased visibility from this was helpful. Companies hate hiring an unknown quantity and my blog proved some of my abilities.

I also remember one particular interview, at Google, with Steve Yegge. Steve asked me about the various steps a compiler goes through when consuming a source file. One of those steps was lexing, and I didn’t know that, ‘cause I missed compiler class due to failing out of university. But while I didn’t know that about compilers there was a lot that I did know, and I managed to change the subject to link-time-code-generation. I spent a good chunk of the interview explaining how this works and it’s non-obvious benefits and I suspect that I got a glowing review based on this lucky save.

I made sure that all of the companies knew that I was talking to the others, to ensure that they would give their best offers. Then I negotiated for a little bit more, because why not? I also used the rhetorical device of “this offer looks great to me, but my spouse is really concerned about the cost of sending our kids to university so…” – it doesn’t hurt.

I agonized over the choice for a while until I realized that Google offered the shortest commute, had an on-site gym and free food, the best compensation, the most promising job opportunities, and an engineering culture that I admired. Done.

Google lived up to their promise. I was given the freedom to focus my attention where it seemed worthwhile, which included chasing bugs that I discovered, along with those sent to me by my peers. I found serious bugs in Windows, Visual Studio, Chrome, and a host of third-party software. Working at Google/Chrome scale was an amazing experience – it exposed issues that would normally never be seen. Just a few of the hundreds of issues I had the pleasure of uncovering or fixing include:

- Occasional failures in Chrome’s build system turned out to be a disk-cache bug in Windows

- A set of impossible crashes in Chrome turned out to be a device driver that was not restoring registers (resuming a pattern first seen in 1987 at Cavedog)

- A set of impossible crashes in Chrome turned out to be a CPU bug (this time it was an implementation bug rather than a design bug)

- A set of impossible crashes in Chrome turned out to be a bug in Microsoft’s x86 emulator (Windows for ARM emulating x86) – I landed a workaround while waiting for a fix

- Slowdowns in loading Chrome’s enormous test binaries turned out to be due to a accidentally quadratic algorithm in Windows

I stayed at Google for ten years, continuing my pattern of not shipping any features. Google was a great fit for me because they let me be self directed (unlike my later years at Microsoft) and they appreciated my work (unlike Valve).

I stayed at Google for ten years, continuing my pattern of not shipping any features. Google was a great fit for me because they let me be self directed (unlike my later years at Microsoft) and they appreciated my work (unlike Valve).

If you stay too long at one company then your compensation may stagnate, because companies are happy to pay you below market rates if you do nothing to prevent this. In my case my sign-on stock grant had become quite valuable over my first four years as Google stock rocketed upwards and when those monthly grant vests stopped after four years my compensation dropped significantly. Even though I had received refresher grants ever year the economic reality was that that sign-on grant was bigger, and granted at a lower stock price, and stock grants had become the majority of my compensation. I was still being paid well, but I knew that I could get a bump back up by moving somewhere else and getting a new sign-on grant.

I didn’t want to leave Google, and they didn’t want to give me more stock. Unless they had to. So the advice I was given was to interview elsewhere, get an offer, give it to my manager and see what happened. You can disapprove if you want, but this is the game that you must play if you want to maximize earnings. I interviewed at <company X> that I did not want to work at, got an offer, and Google played their part in this charade by making a counter offer which I happily accepted. I could have done this game again when the second large stock grant finished vesting, but I lacked the stomach for it and I was almost done at that point anyway.

Retirement – 2024 to ???

After my wife died in 2023 I reassessed my life and decided that I wasn’t enjoying work enough anymore. I wasn’t finding amazing problems to solve as frequently. I had cut back my hours to improve my work-life balance but this meant that meetings – which continued at the same rate – became a larger percentage of my work time. I was working from home in a new city (we moved back to Vancouver in 2022) and I wanted to focus my time on hobbies and making friends, rather than working alone. I talked to my financial adviser and they advised me that I could stop if I wanted to. I took a three-month leave of absence as a trial run, loved it, and quit on my ten-year anniversary. It’s been over a year now and, to the surprise of me from five years earlier, I don’t miss work at all.

In hindsight I got out at an excellent time. I have no enthusiasm for AI and I avoided having to learn it, or compete with it. I’m loving the freedom to play tennis whenever I want and take vacations without counting the days.

Ruminations

As I realized that I preferred fixing code rather than writing code I realized that this meant that it was critical that I work at a large company. With the big teams at Microsoft and Google there were always enough new and interesting issues being created to keep me busy. That plus the huge number of customers and the importance of improving the build pipeline meant that I could always add value. If I could make Chrome build five percent faster, or make Chrome use a few percent fewer CPU cycles, or crash slightly less frequently then I could justify my existence (and sometimes the change was much more than a few percent) by improving the experience for large numbers of coworkers and enormous numbers of users. In a smaller company I would have needed to buckle down and write some features – and I’d mostly forgotten how to do that. The correct company size is a very personal choice but for me “large” was the only option.

My desire to focus on large companies meant that a startup was never going to happen, and that’s fine. The theoretical riches of startups almost never pan out – the expected value is really not worth it.

At my first couple of programming jobs I worked long hours due to pressure from management. This was probably okay because it helped me master my craft a bit faster. As I progressed through my career I mostly pulled back on the hours worked. I don’t know exactly how much I was working at the end, and it did depend on how interesting a puzzle I was solving, but somewhere around 40 hours a week I think. The more I got paid, the less I worked. Or vice-versa.

The point of that, I guess, is that you should be sure that you don’t sacrifice vacations, family time, and hobbies to your job. Taking the time to have friends and a diverse range of activities is crucial.

Skills learned

Software development requires constant reinvention. New languages are a given, but so are new techniques, so plan to stay open to keeping up as long as you are working. Some skills that I learned over the years include:

- C, C++, Python, assembly languages (6502, 68000, PowerPC, x86, x64, ARM) In addition to learning these languages I learned, at Google, that with enough test coverage, code reviewing, and pattern matching it is possible to fix bugs in languages that you do not know at all

- While I never learned parsing, lexing, or other compiler implementation skills I did learn how to “think like a C compiler” which turns out to be extremely useful when understanding how to make a compiler generate efficient code. A lot of this comes down to realizing what optimizations the compiler can do, and which (perhaps due to aliasing) it cannot.

- Version control, various types

- Windbg and Visual Studio arcana

- ETW, perf, various other profiling tools

- Various Xbox and Xbox 360 profiling tools

- So much more

Lessons learned:

- Interview practice matters. If you’re not naturally good at interviews you will be at a disadvantage but you can try to mitigate that

- Talk to other developers about compensation. You can read compensation guides all day but it’s more useful to talk to developers at your level and above and ask them how they are being paid

- Don’t stay too long at any one job. Or, at least, don’t go too long without interviewing

- Keep learning. Always. New languages, tools, techniques, everything.

- Have fun, both in work and outside of work. Don’t save all your enjoyment for retirement