- 30 Nov, 2025 *

Table of Contents

Intro Lore and Motivation - Yapping about why I wrote this post and giving a brief on territory we are about to venture in 1.

Tips to hit prompt cache more consistently - Why prompt caching matters and how to improve cache hits 1.

LLM inference basics - Prefill, decode, and KV caching fundamentals 1.

The memory problem - Why naive KV cache allocation doesn’t scale 1.

Paged attention - vLLM’s OS-inspired solution with blocks and block tables 1.

Prefix caching - Block hashing, longest cache hit, and the full picture

Prerequisite: Sections 2 onwards assumes familiarity with self-attention in deco…

- 30 Nov, 2025 *

Table of Contents

Intro Lore and Motivation - Yapping about why I wrote this post and giving a brief on territory we are about to venture in 1.

Tips to hit prompt cache more consistently - Why prompt caching matters and how to improve cache hits 1.

LLM inference basics - Prefill, decode, and KV caching fundamentals 1.

The memory problem - Why naive KV cache allocation doesn’t scale 1.

Paged attention - vLLM’s OS-inspired solution with blocks and block tables 1.

Prefix caching - Block hashing, longest cache hit, and the full picture

Prerequisite: Sections 2 onwards assumes familiarity with self-attention in decoder transformers. Refer nanoGPT or 3blue1brown.

Intro Lore and Motivation

Recently at work, I had to build a feature on a tight deadline. It involved chat plus tool calling components. I didn’t give much thought to prompt caching as I was just trying to ship v0.

Following next week I started to optimise it and started realising some silly mistakes I had made under pressure. I ended up adding long user-specific data at the end of system prompt thinking that I just need to keep the longest prefix stable for a single conversation / messages array.

A messages array would look like

0. [system prompt + tool definitions]

1. user: what's up. please build this feature for me

2. assistant: can you tell me where to look, it's a big codebase

3. user: look into kv_caching folder

4. assistant: you're absolutely right! i will look there

5. tool output: *greps* *reads*

6. assistant: llm gets output for observation

7. user: ...

8. assistant: ...

My expectation was to hit cache at point 4 for this session - correct, since points 0-3 repeat. But I missed the bigger picture: cache hits can start at point 0 across different users. Your system prompt can be shared across all conversations from your API key org.

My mental model was wrong. I was thinking of inference as a synchronous engine - a single blocking process for one user, like hosting a model locally. First prompt → model does prefill → generates KV cache → responds. Second prompt → hit the cache → fast response.

But this is not how models are deployed at scale by providers like OpenAI and Anthropic. They need to handle concurrent user requests. They do so via async distributed (multi-GPU, multi-node) systems. When the word async comes up, you should get an image of schedulers and message queues in your mind.

These engines incorporate several techniques that optimise LLM inference like KV-cache reuse, continuous batching, chunked prefill, speculative decoding, and more. KV-cache re-use enables prompt caching.

To understand how prompt caching works, we will also need to look at basics of inference engine like vLLM and subsequently how kv-cache re-use is implemented.

Why This Post Exists

I could find amazing tips for prompt caching but was unable to find a comprehensive resource on how prompt caching works under the hood. So here I am load-bearing the responsibility and suffering to write the post. Following “Be the change you want to see in the world” etc. When somebody searches “how does prompt caching work really”, my hope is this post pops-up and gives them a good idea of how prompt caching works with the bonus of learning how inference looks like at scale.

I spent a lot of time wrapping my head around vLLM engine and inference techniques in the last few days to write this post. This was me a few days back.

Literally me

For a long time I thought prompt caching works due to kv-caching which was partially true. However, it works due to actually re-using the kv-cache via different techniques like paged-attention and radix-attention. In this post, I focus on paged-attention. For that purpose, we would require to look at how vLLM engine works. The aim of this post is to “grok prompt caching” so I will focus on parts of vLLM engine that are super-relevant for paged-attention and prefix-caching.

Before we get to the internals, let me start with tips to hit prompt cache more consistently. These are actually what got me curious enough to figure out how everything works under the hood.

Tips to hit prompt cache more consistently

Prompt caching is when LLM providers reuse previously computed key-value tensors for identical prompt prefixes, skipping redundant computation. When you hit the cache, you pay less and get faster responses.

Prompt caching basics and why even worry about it

If you use Codex/Claude Code/Cursor and check the API usage, you will notice a lot of the tokens are “cached”. Luckily code is structured and multiple queries can attend to same context/prefixes to answer queries so lots of cache hits. This is what keeps the bills in control.

Code generation agents are a good example where the context grows very quickly and your input to output token ratio can be very large (which means prefill/decoding ratio is gonna be large - these are crucial concepts that I will cover in next few sections).

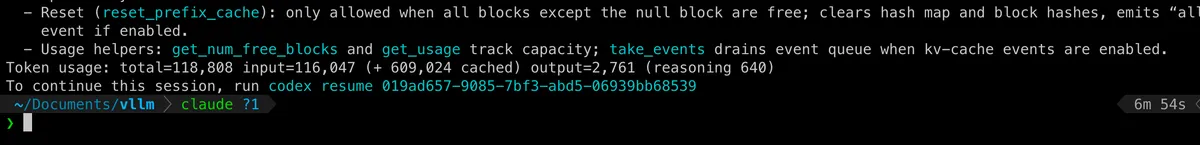

Codex shows cached tokens at end of session

This is where prompt caching saves you. Upto 10x savings on input tokens when the cache hits. You also get faster responses. As you can see in the image below, Sonnet 4.5 costs 1/10th on input tokens on cache hits.

anthropic is so greedy. they literally charge more on base price if you try to use prompt caching lol pic.twitter.com/kXVOw5SNGx

— sankalp (@dejavucoder) November 17, 2025

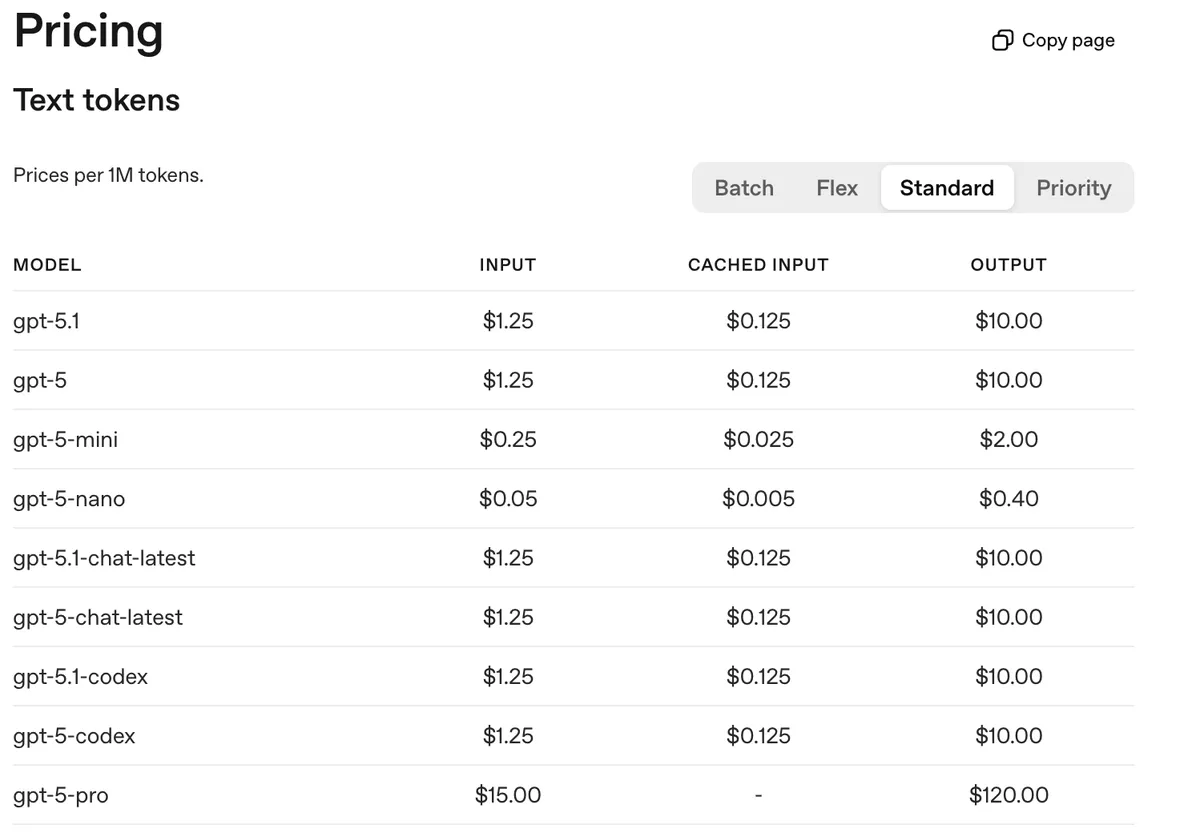

OpenAI prompt caching pricing - note no extra cost for storing tokens in cache

I was calling Anthropic greedy because they charge more for cache writes (and Sonnet/Opus already cost a lot). In comparison, OpenAI doesn’t charge extra. That’s a consumer lens. From a based engineer lens, storing key-value tensors in GPU VRAM or GPU-local storage has a cost - which explains the extra charge, as we’ll see later in this post.

Semi-related but OpenAI also recently rolled out 24 hour cache retention policy for the GPT-5.1 series and GPT-4.1 model. By default, cached prefixes stay in GPU VRAM for 5-10 minutes of inactivity. The extended 24hr retention offloads KV tensors to GPU-local storage (SSDs attached to GPU nodes) when idle, loading them back into VRAM on cache hit.

Below are some different type of LLM call patterns where caching can be useful.

KV cache sharing examples. Blue boxes are shareable prompt parts, green boxes are non-shareable parts, and yellow boxes are non-shareable model outputs. Source: SGLang Blog

Tips to improve cache hits

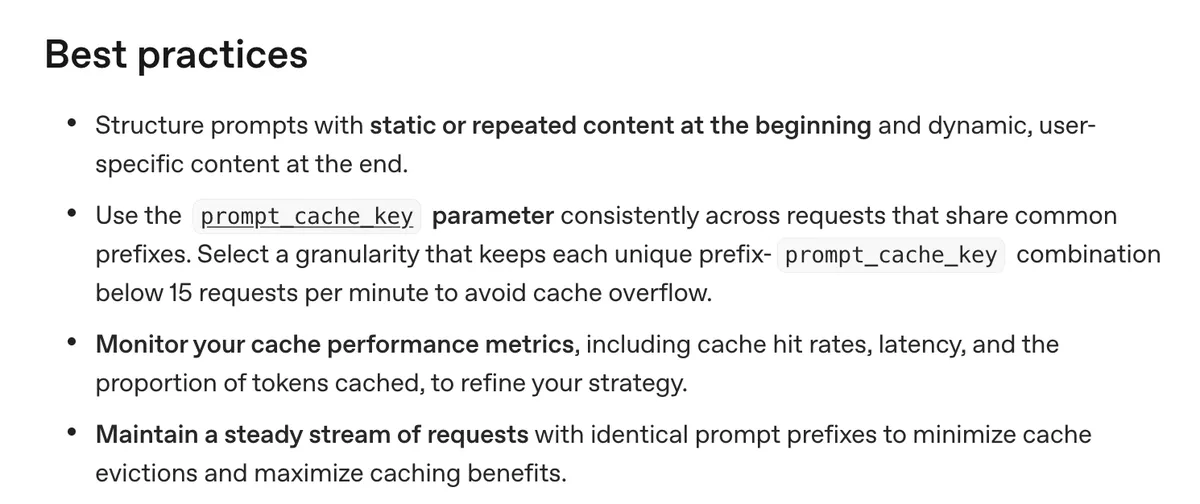

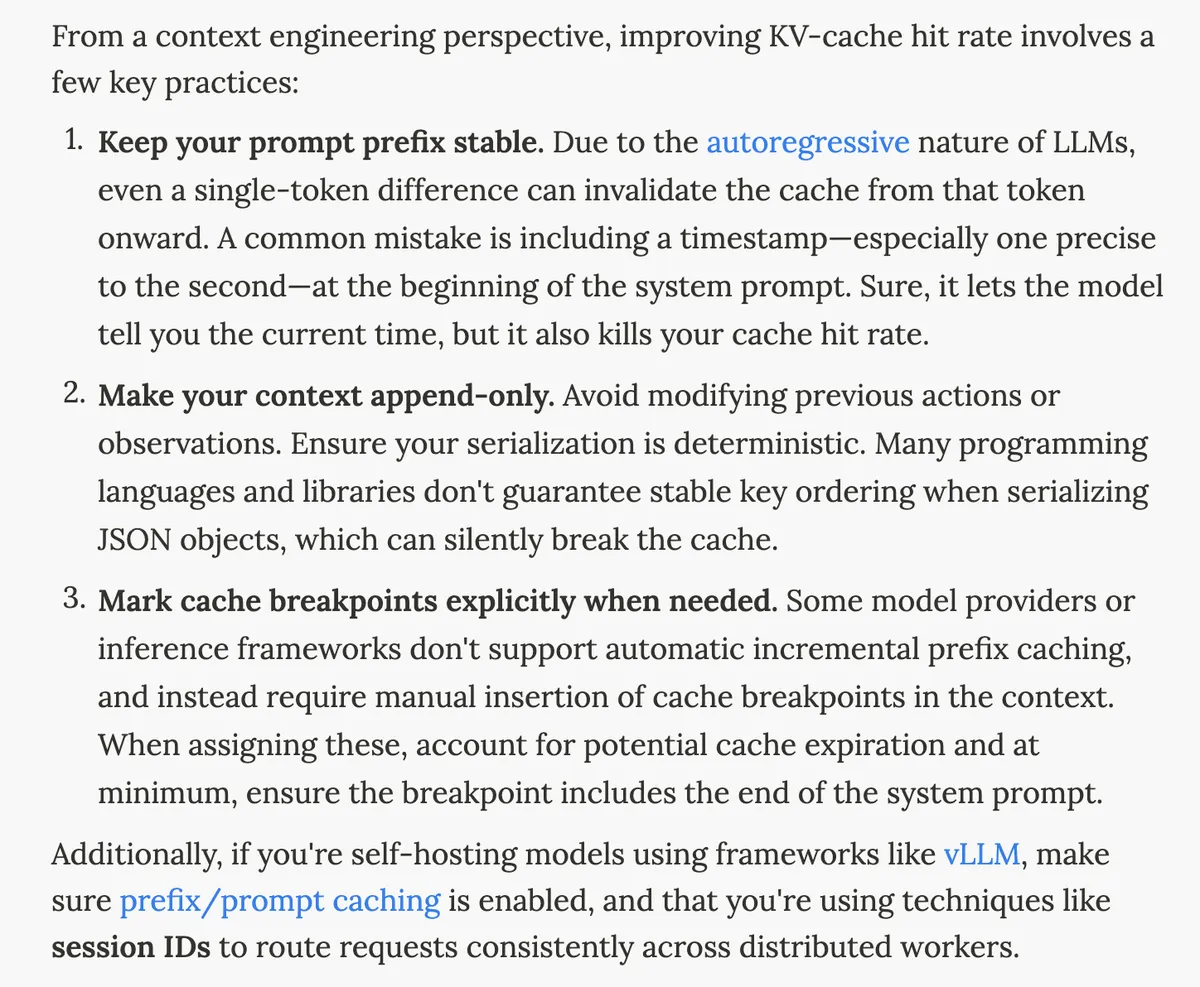

OpenAI and Anthropic offer some tips in their docs. The main idea is to maintain a longest possible stable prefix.

OpenAI suggested practices. Source: OpenAI Docs

I felt these tips were not nuanced and there is a lot of room to make mistakes. I found a better guide in Manus’ super helpful blog’s, the first section specifically.

Manus context engineering tips. Source: Manus Blog

I read this blog and a couple of other resources and ended up making some changes at the work problem I was yapping about at the start.

Make the prefix stable

I ended up removing all the user specific or dynamic content from my system prompt. This made it possible for other users to hit prompt cache even for the system prompt message as it will be a common prefix in the “kv-cache blocks” (more on this later)

Keep context append-only

In the feature I was building, there could be multiple tool calls and their moderately long outputs were getting stored in the messages array. I thought that this may degrade performance due to context rot for longer conversation so I was truncating just the tool call outputs in the messages array upon the conversation getting longer.

In reality, I was breaking the prefix due to this so I decided to stop the truncation as I preferred the cost and latency benefits. Now my context was append-only.

I am guessing Claude Code’s compaction is likely an append only process.

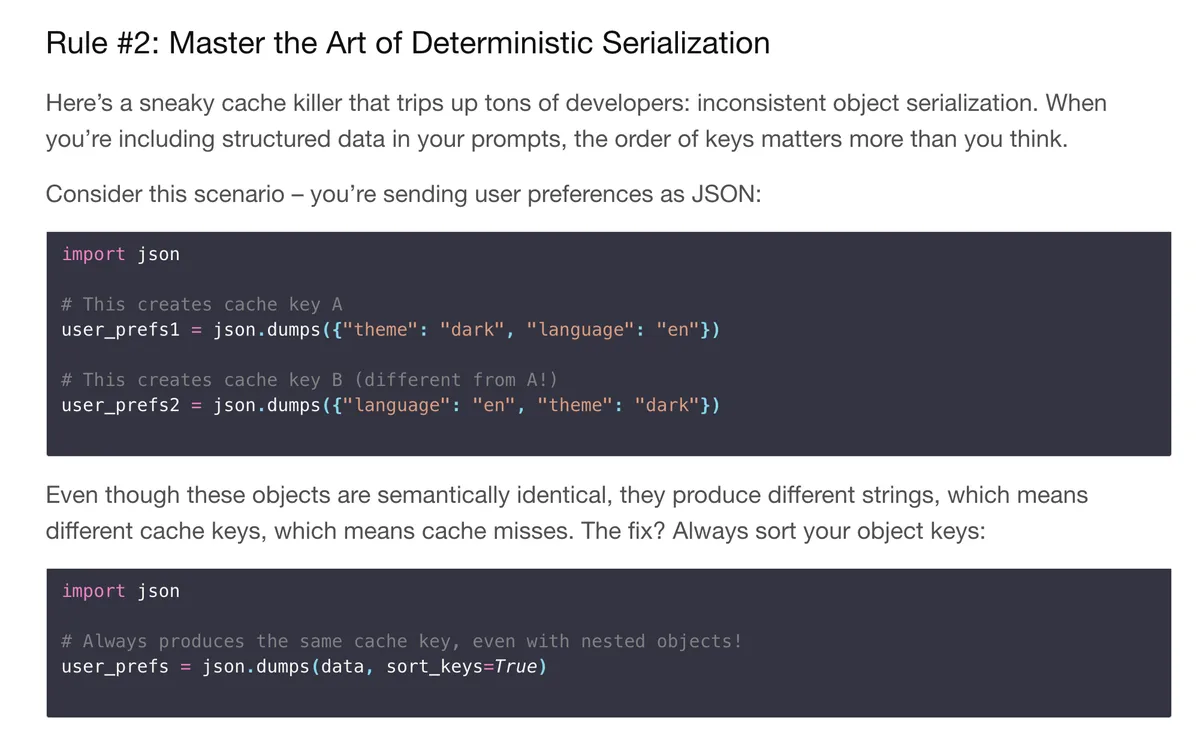

Use deterministic serialization

Manus blog mentions to have deterministic serialization. I ended up using sort_keys=True when serializing JSON in tool call outputs. Even if two objects are semantically identical, different key ordering produces different strings - which means different cache keys and cache misses. I knew about the first two but I didn’t think about this point.

- Use `sort_keys=True` in `json.dumps()` to ensure consistent key ordering. This blog benchmarks cost difference of prompt caching. Source: Ankit’s Blog*

Don’t change tool call definitions dynamically

Manus mentioned another important thing to keep in mind - tool call definitions are usually stored before or after the system prompt. Refer here. This means changing or removing certain tool call definitions will break the entire prefix afterwards the point of change.

Anthropic recently launched a Tool Search Tool which searches for tools on demand. You don’t need to mention all tools upfront. I wondered if it would break caching because tools usually sit at start or end of system prompt internally. Later I saw in the docs that these tool definitions are “appended” to the context - so it stays append-only.

tool call definitions sit before or after the system prompt so this is a cool approach although i wonder if the model brings up a new tool in middle of execution. won’t it break prompt caching? https://t.co/zVRkU0f5dh

— sankalp (@dejavucoder) November 24, 2025

prompt_cache_key and cache_control

For OpenAI, your API request needs to get routed to the same machine to hit the cache. OpenAI routes based on a hash of the initial prefix (~256 tokens). You can pass a prompt_cache_key parameter which gets combined with this prefix hash, helping you influence routing when many requests share long common prefixes. Note that this is not a cache breakpoint parameter - it’s a routing hint. This is something I need to experiment more with too.

For Anthropic, I think they don’t have automatic prefix caching (not 100% sure) so you need to explicitly mark cache_control breakpoints to tell them where to cache (as mentioned in Manus’ point 3). From each breakpoint, Anthropic checks backwards to find the longest cached prefix, with a 20-block lookback window per breakpoint.

LLM inference basics

Now that we are done with the practical stuff, let’s see things under the hood. You may wonder if there is a reason to spend time looking into things under hood (besides curiosity and building conviction). I think when it comes to optimising stuff at any layer of the stack (especially application/engineering layer), going down the abstractions can help tremendously. Sometimes people don’t have any other option but to look at the building blocks and figure out solutions from there.

This has been my experience in the past and was reminded after reading Manus’ blog. Those guys were able to optimise because they knew about how things worked under the hood.

Prefill and decoding

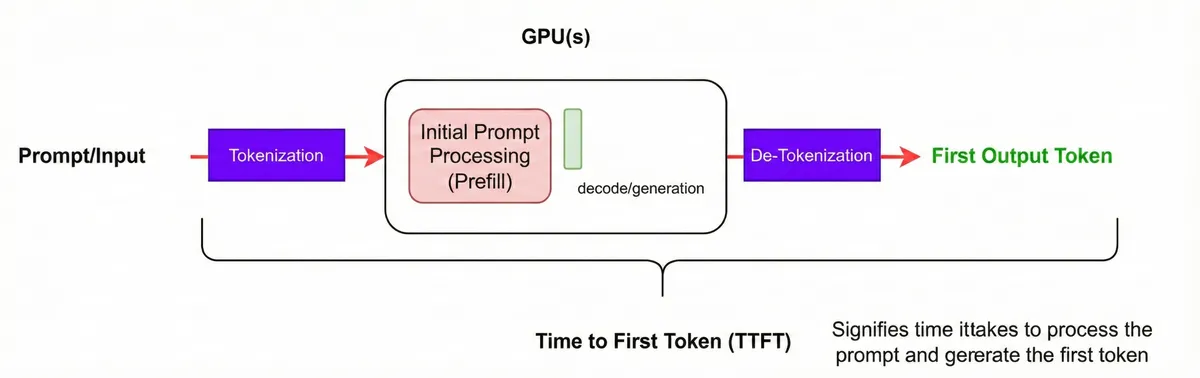

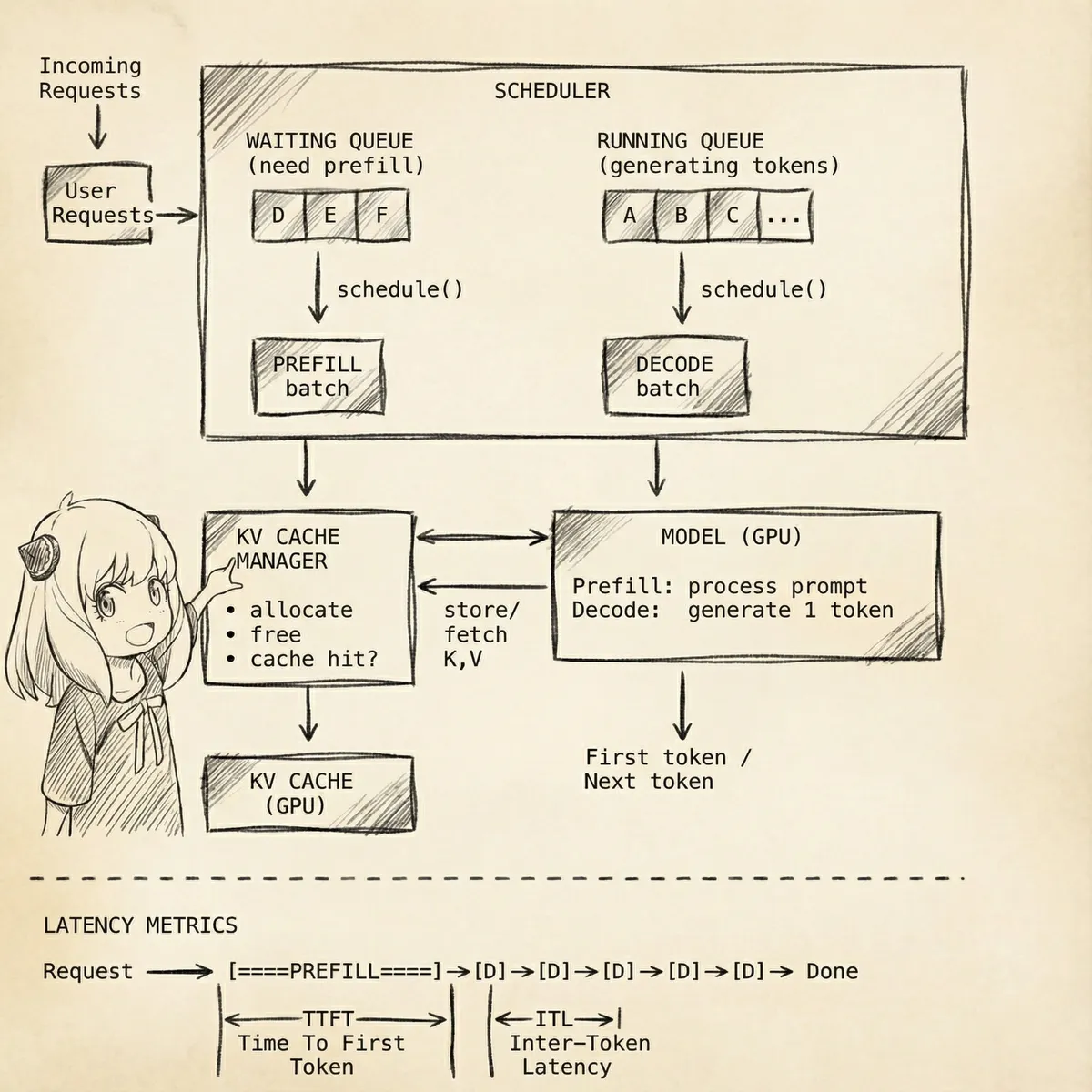

There are two stages (or rather requests) as to how LLM inference works - prefill (input processing to get first token) and decode (output generation).

Time to first token (TTFT). Source: NVIDIA NIM Docs

Consider an input prompt -> “The capital of France is” aka the “Prefill” mode.

During prefill, the model processes the entire prompt. Each token attends to previous tokens via causal self-attention, calculating Query, Key, and Value tensors across all transformer layers to produce the first output token. This is a highly parallel step (thanks to matrix multiplication) and is heavily compute/GPU FLOPs bound. Much more computation steps than memory moving around steps. More arithmetic stuff here

In contrast, decode is memory-bound - each step processes just 1 token but must load the entire KV cache from GPU memory. This compute vs memory distinction matters for scheduling: vLLM prioritizes the running queue (decode) over the waiting queue (prefill), ensuring latency-sensitive decode steps aren’t starved by compute-heavy prefills. Chunked prefill extends this by capping prefill tokens per batch, letting decode requests proceed without waiting.

# source: [nanoGPT](https://github.com/karpathy/nanoGPT/blob/3adf61e154c3fe3fca428ad6bc3818b27a3b8291/model.py#L29)

def forward(self, x):

B, T, C = x.size() # batch size, sequence length, embedding dimensionality (n_embd)

# prefill - calculate query, key, values for all heads in batch and move head forward to be the batch dim

q, k, v = self.c_attn(x).split(self.n_embd, dim=2)

k = k.view(B, T, self.n_head, C // self.n_head).transpose(1, 2) # (B, nh, T, hs)

q = q.view(B, T, self.n_head, C // self.n_head).transpose(1, 2) # (B, nh, T, hs)

v = v.view(B, T, self.n_head, C // self.n_head).transpose(1, 2) # (B, nh, T, hs)

Once prefill is done, decode begins. We take the output token and append it to input sequence and pass it through the LLM (auto-regressive generation). This process repeats till we get end of sequence token.

Dry run:

Prefill

[The capital of France is] → Paris

Decode iteration 1

[The Capital of France is Paris] → which

Decode iteration 2

[The Capital of France is Paris which] → has

Decode iteration 3

[The Capital of France is Paris which has] → the

Decode iteration 4

[The Capital of France is Paris which has the] → Eiffel

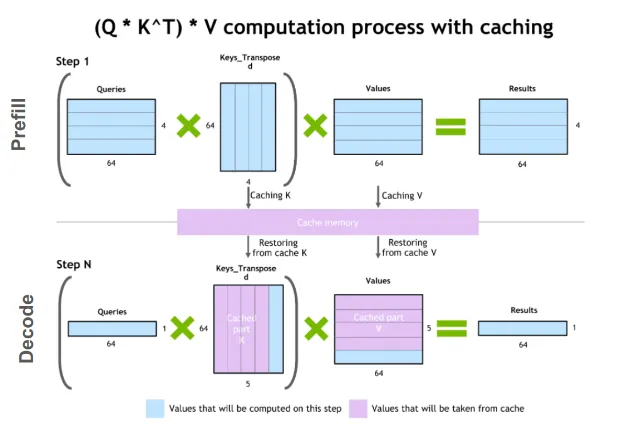

Observation 1: At each decode iteration, we’re recomputing KV tensors for all previous tokens - that’s wasteful:

[The]→K₁V₁ [Capital]→K₂V₂ [of]→K₃V₃ [France]→K₄V₄ [is]→K₅V₅ [Paris]→K₆V₆ [which]→K₇V₇ [has]→K₈V₈ → [the]

WASTE WASTE WASTE WASTE WASTE WASTE WASTE NEW

Observation 2: x in q, k, v = self.c_attn(x).split(self.n_embd, dim=2) is the embedding of the input prompt. For the sake of simplicity, I will just write the English version. For iteration 1, x would be “The Capital of France is Paris”. For iteration 2, x would be “The Capital of France is Paris which”. We are processing the same input sentence repeatedly and the KV tensors are getting re-calculated.

KV caching

This happens because LLMs are stateless. But luckily you can just do things and add state.

You can store the KV tensors for the input prompt in GPU memory and re-use them. When we do this, the iterations change to

Prefill (with cache)

Model view: x = [The capital of France is]

Output: Paris

We compute and store K/V for: [The], [capital], [of], [France], [is]

→ KV cache now has entries for the whole prefix.

Now decode. At each step, we only feed the new token through the projections and append its K/V to the cache. The full context is reconstructed by “prefix from cache + new token”.

Decode iteration 1

Model view: x = [Paris] (only the new token)

Cache: K/V for [The capital of France is] + [Paris]

Output: which

We compute K/V just for [Paris] and append it to the existing cache.

Decode iteration 2

Model view: x = [which]

Cache: K/V for [The capital of France is Paris] + [which]

Output: has

Decode iteration 3

Model view: x = [has]

Cache: K/V for [The capital of France is Paris which] + [has]

Output: the

Decode iteration 4

Model view: x = [the]

Cache: K/V for [The capital of France is Paris which has] + [the]

Output: Eiffel

The decode process now just happens for only 1 token per step and rest we hit the kv-cache. Adding to kv-cache is a O(1) operation. In most scenarios like long documents and code, the input context/prompt tends to be much larger than the number of output tokens. In other words, the prefill to decode ratio is big so we benefit in latency and cost due to this.

Optional KV-cache code walkthrough

The code changes are mainly around three things -

- Allocating memory in GPU

- Concatenation of new k/v tensor

- Causal Mask related changes - when you have only a single query / 1 token to decode, no causal mask is required as this is the last token so it’s allowed to see everything before it

A good reference for kv-cache code is Karpathy sensei’s nanochat. You can access my minimal code walkthrough of nanochat here.

A simpler code reference is available here by Sebastian Raschka.

The memory problem

Traditional KV cache - contiguous memory allocation per request

The problem is we need to store the kv-cache somewhere - in GPU memory. The easiest approach is to allocate one big chunk of GPU memory per request but this is not good for serving at scale and leads to several challenges.

Scaling problem

KV cache size grows linearly with sequence length / context:

kv_size = 2 (K+V) × layers × kv_heads × head_dim × seq_len × precision

For a 7B model (32 layers, 32 KV heads, 128 head_dim, float16 = 2 bytes):

- Per token: 2 × 32 × 32 × 128 × 2 bytes ≈ 0.5 MB

- 1K context: ~512 MB per request

- 100 concurrent requests: ~50 GB just for KV cache

Classic memory problems

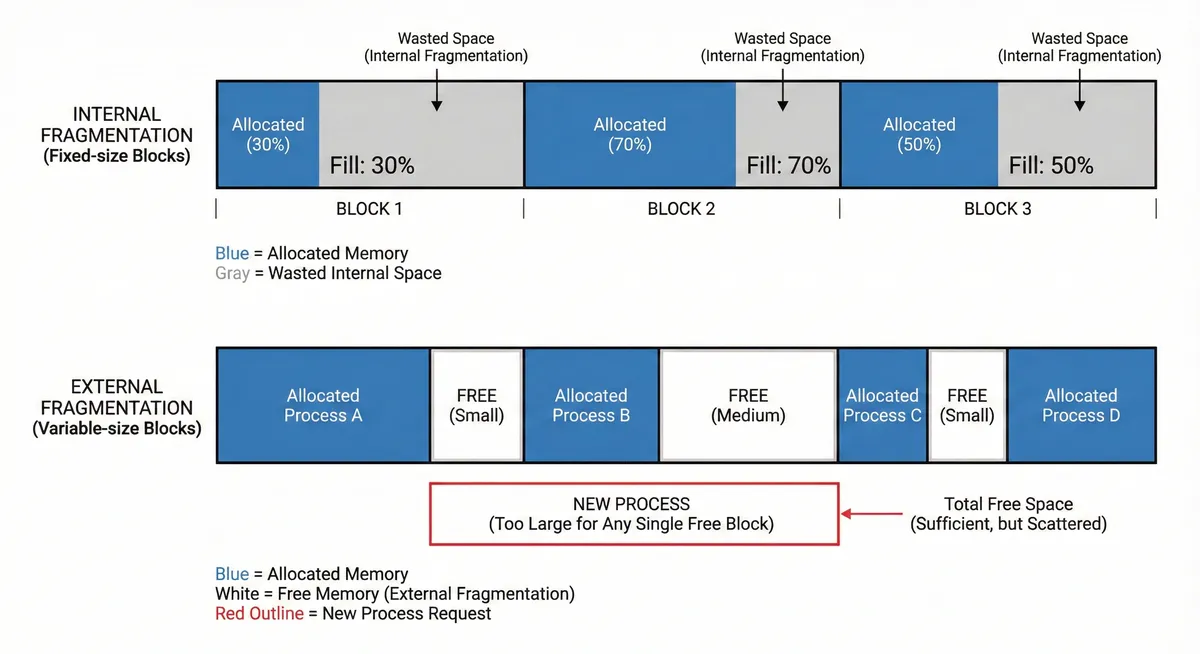

These are classic OS memory allocation problems:

Internal Fragmentation: Unused space within an allocated block. Occurs when allocated memory is larger than what’s actually needed, and the excess cannot be used by other processes. 1.

External Fragmentation: Unusable space between allocated blocks. Occurs when free memory is split into small non-contiguous chunks, making it impossible to allocate large contiguous blocks even when total free memory is sufficient.

Internal and external fragmentation in OS memory allocation

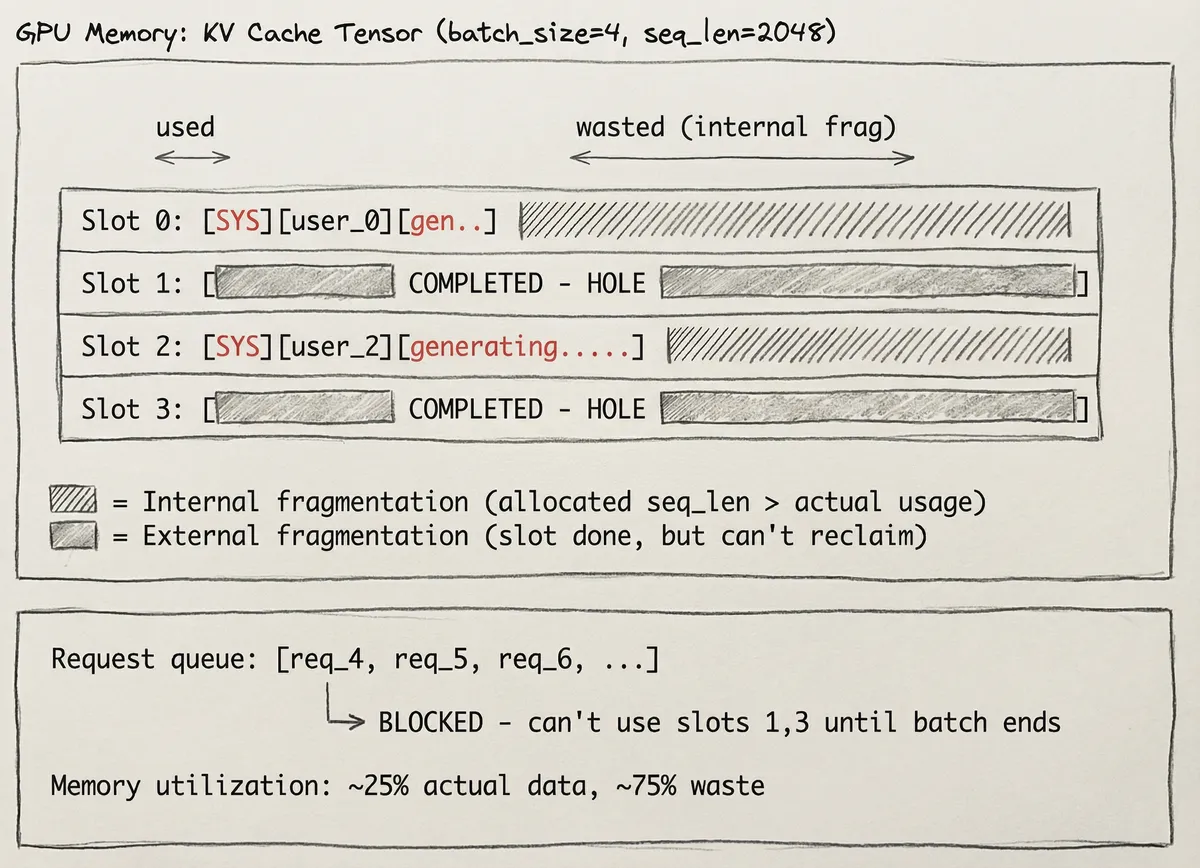

For KV cache, these problems manifest as:

- Internal: We pre-allocate memory for max sequence length. If a request uses 100 tokens but we allocated for 1024, the remaining 924 tokens worth of memory sits unused.

- External: Requests finish at different times, leaving scattered gaps in GPU memory. A new request needing a contiguous 512-token block might fail even if 512 tokens worth of free memory exists in smaller fragments.

Internal and external fragmentation in KV cache memory. Source: vLLM Paper

Redundancy

Besides memory problems, identical prefixes are going to stored multiple times. 100 requests with same system prompt = 100 copies of the same kv cache. If only we had blocks and pointers... like how operating systems solved this exact problem decades ago.

OS paging - virtual to physical memory mapping via page table

Lastly traditional kv-cache is per-request - it’s discarded after the LLM call generation is complete. No sharing across different requests.

Towards better memory allocation solutions for kv-cache re-use aka prompt caching

Different engines solve for automatic prefix-caching via different solutions.

Paged Attention (vLLM inference engine)

Berkeley researchers introduced page-attention to solve this and they built the vLLM inference engine v0.

In OS paging, we break one big contigous chunk of RAM into fixed size pages and give the process a page table that maps virtual (CPU) to physical address (RAM). Pages can be scattered anywhere in physical memory/RAM. The idea is to model the kv cache in a way that is similar to paging in operating systems.

Radix Attention (SGLang inference engine)

SGLang solves for prompt-caching via Radix attention that utilises a radix-tree. You can check out blog and video.

Paged attention

Inference engine overview

Inference engines have to handle concurrent user requests in a async, real-time manner. They are hosted on distributed GPU setup. These typically have a scheduler which helps to schedule requests like prefill/decode and does other kind of orchestration.

Basic inference optimisation techniques these engines usually support include kv-cache re-use, continuous batching (also known as in-flight batching), and chunked-prefill. These three are designed for fast asynchronous generation. Other common optimisations include torch native optimisations (torch.ao, compile etc.), speculative decoding, and quantised kv-caching. These engines also support multiple attention architectures so that models of different architectures can be served.

Simplified vLLM engine overview

Time to get to paged attention now.

How it works

Instead of allocating one big chunk of memory for kv-cache, vLLM pre-allocates a pool of fixed size blocks (fixed GPU memory) at startup. All these reside in a FreeKVCacheBlockQueue#free_block_queue. These blocks by default have space for 16 tokens. This is the same idea as OS paging where we have fixed-size pages, scattered in physical memory, managed via a page table.

Each block is represented by a KVCacheBlock:

@dataclass

class KVCacheBlock:

block_id: int

ref_cnt: int = 0

_block_hash: BlockHashWithGroupId | None = None

block_id- which physical GPU memory blockref_cnt- how many requests are using this blockblock_hash- content hash for prefix caching (more on this later)

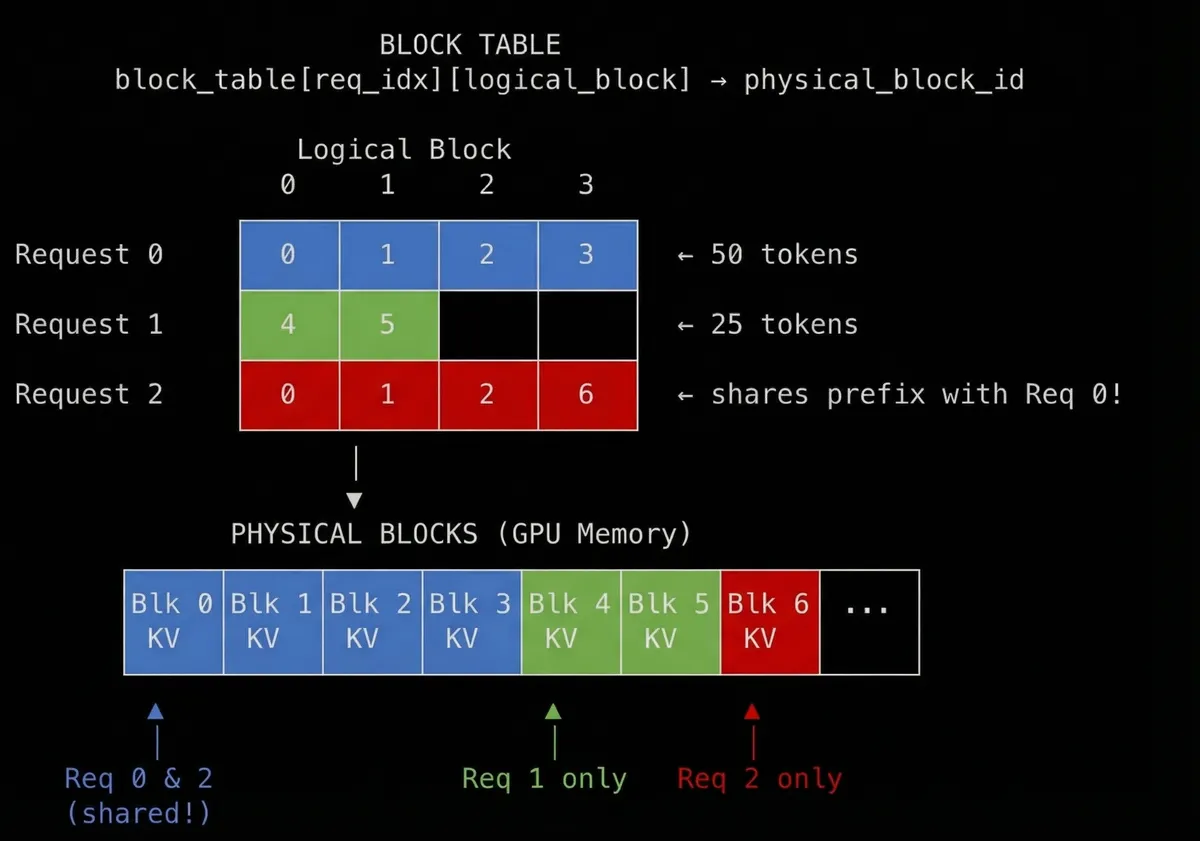

Request to Blocks - Logical Mapping

When a request arrives, tokens are first mapped to logical block positions:

block_index = token_position // block_size # which block

offset = token_position % block_size # position within block

We map set of 16 tokens into a block logically. A 50 token prompt needs ceil(50/16) = 4 blocks

Request: "The capital of France is Paris which is known for..." (50 tokens)

Token positions: [0-15] [16-31] [32-47] [48-49]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Logical blocks: Block 0 Block 1 Block 2 Block 3

(full) (full) (full) (partial)

This is just math so far in the sense no actual GPU memory has been assigned yet to the block. Next we need to decide which physical blocks to use.

Block Hashing

To solve for this, vLLM uses block hashing. The idea is to calculate content-addressable block hashes based on token IDs. When a request arrives, a block hash is calculated and looked up in a cache. If a hash exists, we reuse the cached block. If not, we pop a block from the free queue and allocate it. These hashes are also stored in a lookup table (next section).

Hashing gives you O(1) lookup per block, whereas comparing token sequences directly against all cached prefixes would be far more expensive.

The hash function:

def hash_block_tokens(

parent_block_hash: BlockHash | None,

curr_block_token_ids: Sequence[int],

extra_keys: tuple[Any, ...] | None = None,

) -> BlockHash:

if not parent_block_hash:

parent_block_hash = NONE_HASH # seed for first block

return BlockHash(

sha256((parent_block_hash, tuple(curr_block_token_ids), extra_keys))

)

Three inputs go into each hash:

parent_block_hash- hash of the previous block (or a seed for block 0)curr_block_token_ids- the token IDs in this blockextra_keys- optional metadata (cache salt, LoRA adapter, multimodal inputs)

Parent block hash is included so that block N’s hash encodes block 0 through N-1. If block 5’s hash matches, blocks 0-4 are guaranteed to be identical - this means one lookup validates an entire prefix. This is core to how prefix caching works.

You might wonder: why not just hash each block independently? The problem is causal attention. Token 32’s KV values depend on tokens 0-31. If I reuse block 2’s cached KV tensors, I’m implicitly assuming blocks 0 and 1 are identical too. Independent hashes can’t guarantee that. Hence parent chaining.

A note on cache isolation: By default, there’s no isolation - the cache is purely content-addressed. If you need tenant isolation, vLLM supports a cache_salt parameter that gets included in the block hash, creating separate cache namespaces per user/tenant.

Hash to block map

Computed hashes are stored in a dictionary called BlockHashToBlockMap:

class BlockHashToBlockMap:

def __init__(self):

self._cache: dict[BlockHashWithGroupId, KVCacheBlock] = {}

def get_one_block(self, key: BlockHashWithGroupId) -> KVCacheBlock | None:

return self._cache.get(key) # O(1) lookup

This hashmap basically tells you - given a hash, is there already a physical block with matching KV tensors?

After the hash lookup, the block table is constructed. This maps the logical positions to physical GPU memory blocks.

Allocation flow

The physical memory (GPU memory) block actually contain space to hold the KV tensors for those tokens. The actual KV tensors are computed and written during the forward pass (prefill). The block table just tells the GPU kernel where to write them.

Block reuse - multiple requests sharing KV cache blocks. Made using Nano Banana Pro

In the diagram, we can see request 0 and request 2 re-uses blocks 0, 1, 2 from request 0. This means they are having same KV tensors because same prefix. If both the requests 0 and 2 are live, the ref_cnt would be 2. When one finishes, ref_cnt = 1. Both finish ref_cnt = 0 and the block goes back to free queue which follows an LRU eviction policy.

Prefix caching

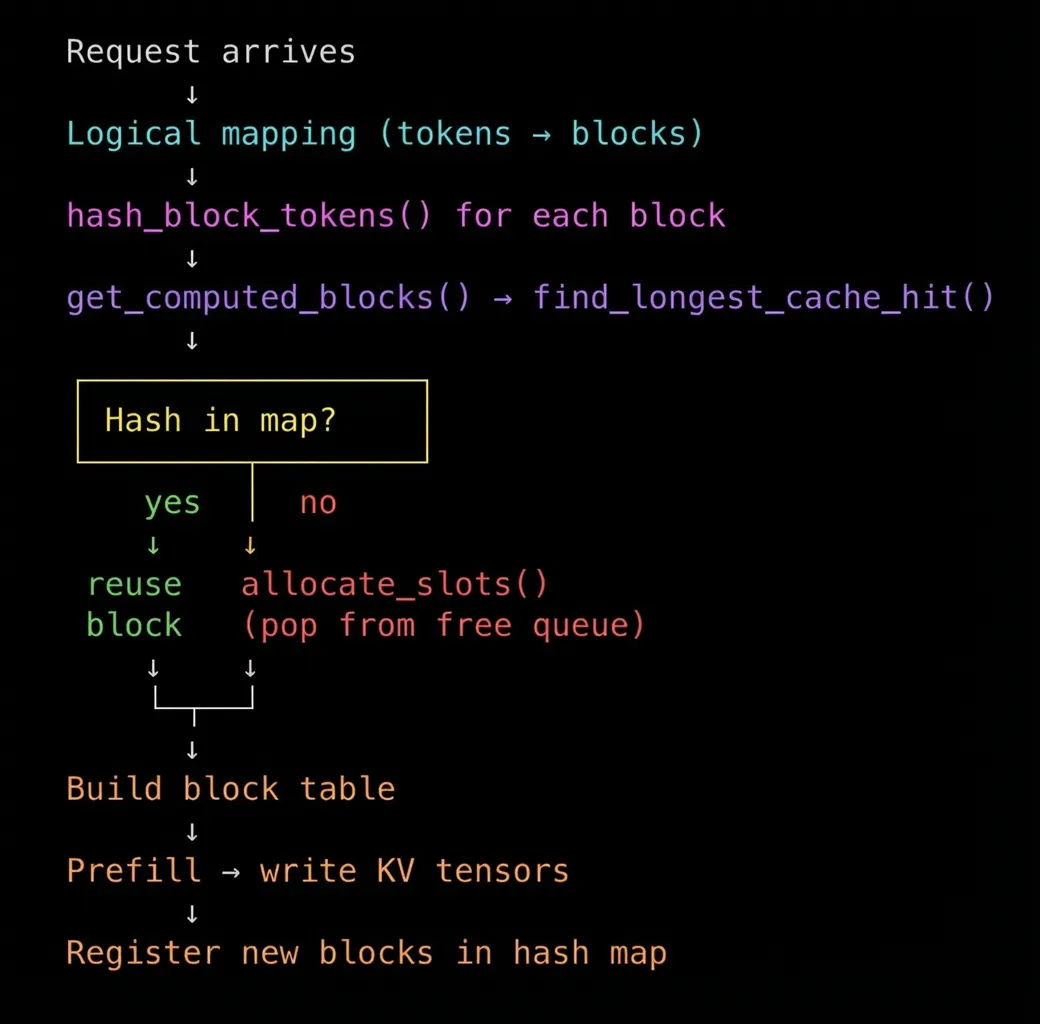

Finally all the building blocks are there to explain how prefix caching works.

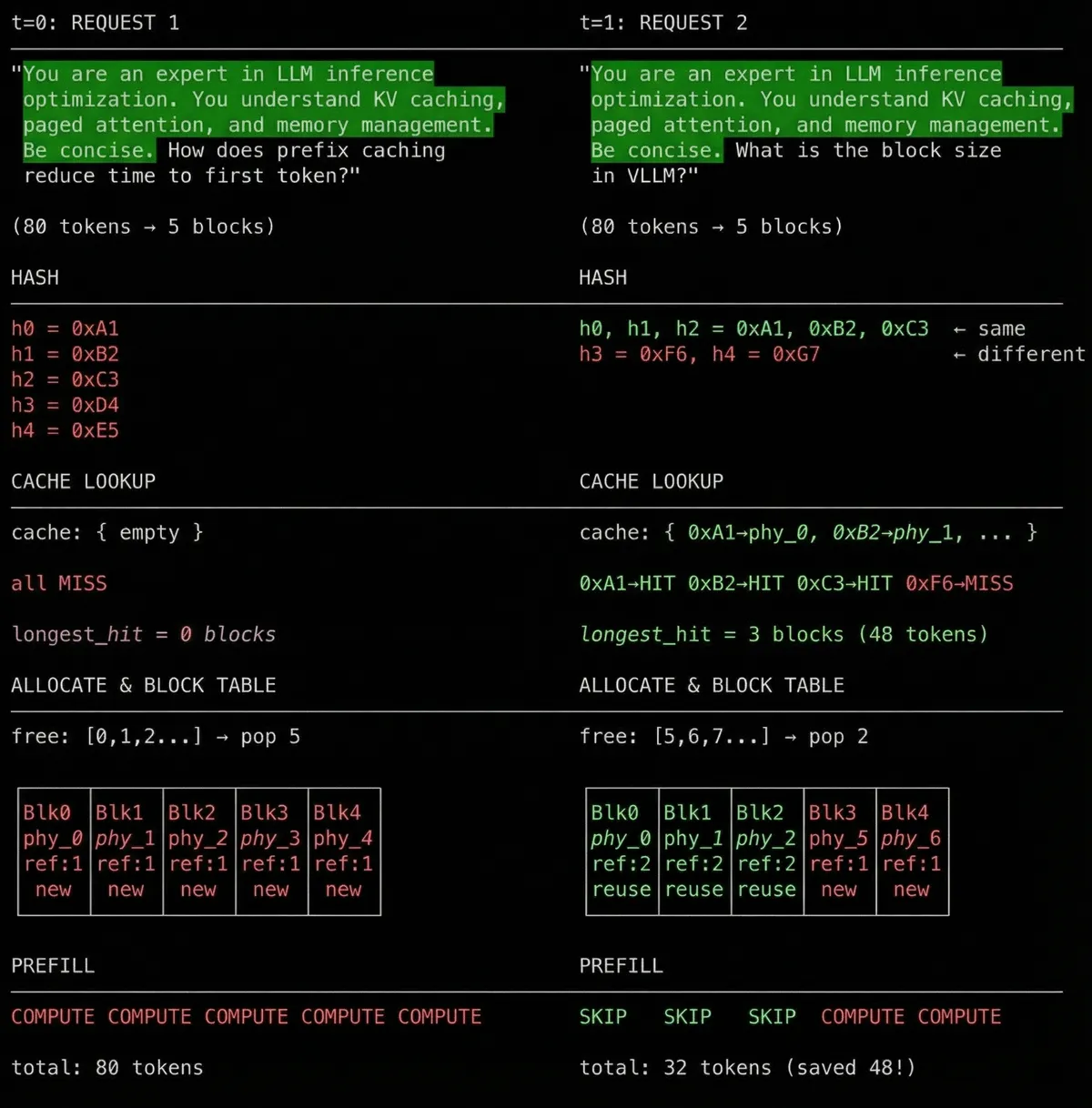

The key insight: cached blocks skip prefill computation. If we can find the longest prefix of cached blocks amongst multiple requests, then we can entirely skip prefill for them.

Why “prefix” though? Reason is causal attention. Each token can only attend to tokens that came before it. If you change anything before it, the KV tensor values at Nth position will differ. Token 50’s KV tensors depend on tokens 0-49. This means KV values are only valid if the entire prefix is identical. You can’t reuse block 3’s KV tensors if blocks 0, 1, or 2 are different - because in that case KV tensor at position 3 would be different.

This is also the reason to use parent hash-chaining.

hash(block 0) = sha256(NONE_HASH, tokens[0:16], extras)

hash(block 1) = sha256(hash(block 0), tokens[16:32], extras)

hash(block 2) = sha256(hash(block 1), tokens[32:48], extras)

Each hash encodes its entire history. If block 2’s hash matches, blocks 0 and 1 are guaranteed identical. One lookup validates the whole prefix. After the block table is built, we know which blocks are cache hits (reused) and which are misses (freshly allocated).

Now we only need to figure out the longest prefix. The scheduler calls get_computed_blocks() before scheduling a request for prefill. This internally calls find_longest_cache_hit() which walks through block hashes sequentially until it hits a miss:

def find_longest_cache_hit(block_hashes, block_pool):

computed_blocks = []

for block_hash in block_hashes:

if cached_block := block_pool.get_cached_block(block_hash):

computed_blocks.append(cached_block)

else:

break # stop at first miss

return computed_blocks

The consecutive hits from block 0 are the cached prefix. Because hashes chain through parents, if block 2’s hash matches, blocks 0 and 1 are guaranteed to match too.

Now during prefill, we only compute KV tensors for the cache misses:

Request: "The capital of France is Paris which..."

[block 0] [block 1] [block 2] [block 3]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Lookup: HIT HIT MISS MISS

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Prefill: [skip] [skip] [compute] [compute]

Blocks 0 and 1 already have KV tensors in GPU memory from a previous request. We don’t recompute; we just point to them in the block table. Prefill only runs for blocks 2 and 3.

And that’s basically it. If you understood till here, that’s the crux of paged attention.

Putting it all together

One dry run

Request 1 arrives, computes all blocks, and starts decoding. While request 1 is still generating tokens, request 2, a completely different request from a different user, arrives. Because they share the same system prompt, request 2 gets cache hits on blocks 0-2 and only needs to compute the new blocks.

Prefix caching dry run - request 2 arrives at t=1 and reuses cached blocks

This is how prompt caching works. Same system prompt = same hash = same cached KV blocks. KV cache blocks can be used across requests. User B benefits from blocks cached by User A.

Conclusion

So it turns out my original mental model was wrong. I was thinking of caching as per-conversation, but it’s actually per-content. Prefix caching works at the token level, not the request level - which is exactly why it works across requests.

I hope you now understand why providers need a static prefix: any change in the prefix breaks the entire hash chain.

If you want to go deeper, continuous batching and chunked-prefill are worth exploring. They weren’t prerequisites here, but they make overall inference more asynchronous and faster. Pretty standard across inference engines.

Thanks for reading! Please share/RT/upvote if you found this useful.

Acknowledgements

Note that this blog is not sponsored by anyone.

I highly recommend reading Aleksa Gordic’s vLLM blog to get an overview of vLLM engine including continous batching and prefill. It was incredibly helpful in understanding the internals.

Thanks to snimu for providing great feedback to improve readability and tips to improve the first half of the post.

Thanks to tokenbender, Himanshu, and Sachin for proofreading - they helped verify the content and improve the overall experience.

This post was written with assistance from Claude Opus 4.5 and Nano Banana Pro.

This post wouldn’t exist without these resources:

Code Reference

This blog is grounded on vLLM v1.

vllm/

├── utils/

│ └── hashing.py

│ └── sha256() # Hash function for block content

│

└── v1/core/

├── kv_cache_utils.py

│ ├── KVCacheBlock # Block metadata (block_id, ref_cnt, hash)

│ ├── hash_block_tokens() # Computes block hash with parent chaining

│ └── BlockHash # Type alias for 32-byte hash

│

├── block_pool.py

│ ├── BlockHashToBlockMap # Hash → KVCacheBlock lookup dictionary

│ └── BlockPool # Manages free queue and cached blocks

│

├── kv_cache_manager.py

│ ├── get_computed_blocks() # Entry point for prefix cache lookup

│ └── allocate_slots() # Allocates blocks for cache misses

│

├── single_type_kv_cache_manager.py

│ └── find_longest_cache_hit() # Walks hashes until first miss

│

└── sched/

└── scheduler.py # Orchestrates the allocation flow

Papers

- Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention - The original vLLM paper by Berkeley researchers

Blogs & Articles

- Baseten Inference Stack - How a production inference stack looks

- Manus Context Engineering - Practical tips for prompt caching optimisation

- Ankit’s Prompt Engineering for KV Cache - Benchmarking on cache hit cost differences

- Transformer Inference Arithmetic - Deep dive into FLOPs vs memory boundedness

- Sebastian Raschka’s KV Cache Guide - Simple code reference for KV caching

- Tool call placement in prompts - Where tool definitions go in the message structure

Videos

- Julien Simon’s LLM Inference Optimisation - Highly recommend for inference basics

- Andrej Karpathy’s nanoGPT - Understanding transformer internals

- 3Blue1Brown Attention Mechanism - Visual explanation of attention

- SGLang Radix Attention - Alternative approach to prefix caching

Code

- Karpathy’s nanochat - Clean KV cache implementation

- vLLM GitHub - The source code I spent my weekend reading

Other

- NVIDIA NIM Metrics - LLM inference metrics reference

- SGLang Blog - Radix attention explanation