As the sky continued to lighten, Sona’s eyes kept travelling to the window and the bend in the road. Should she wait for her brother before heading to get water? If he didn’t find work, he’d ride his bicycle back up the hill to cook breakfast for himself and Sona. She hated to leave him to eat alone, especially if he were discouraged.

Unlike most Nepali boys and men, Samiran Daju liked to cook and boasted about his “magical momo” to anyone who’d listen. Sona didn’t mind the bragging; her brother’s momos were scrumptious. He always told the truth, like the time last year when he’d been accused of stealing a neighbour’s motorcycle and leaving it wrecked somewhere up in the mountains. Samiran Daju had insisted he hadn’t done it, but doubt had flickered even in Ama’s eyes because everyo…

As the sky continued to lighten, Sona’s eyes kept travelling to the window and the bend in the road. Should she wait for her brother before heading to get water? If he didn’t find work, he’d ride his bicycle back up the hill to cook breakfast for himself and Sona. She hated to leave him to eat alone, especially if he were discouraged.

Unlike most Nepali boys and men, Samiran Daju liked to cook and boasted about his “magical momo” to anyone who’d listen. Sona didn’t mind the bragging; her brother’s momos were scrumptious. He always told the truth, like the time last year when he’d been accused of stealing a neighbour’s motorcycle and leaving it wrecked somewhere up in the mountains. Samiran Daju had insisted he hadn’t done it, but doubt had flickered even in Ama’s eyes because everyone knew her son dreamed of owning a motorcycle. Their village had branded him as a thief with a word that was the same in Bangla and Nepali: “chor.” Schoolboys still hissed it when he passed them in the road. Only Sona had believed her brother. She and Kutu had nosed around until they’d found the Honda Dio tucked away in the neighbour’s cousin’s shed, hidden there in an effort to frame Samiran Daju.

Thanks to gossip, though, shame still clung to Sona’s whole family like muddy residue. Ama still teared up sometimes, remembering how close her son had come to being arrested. The false accusation was why the manager wouldn’t hire Samiran Daju for any job on the plantation; it was the reason people hadn’t patronised his tea and snack stall. But her brother wasn’t giving up; he’d promised Sona he’d pay back that loan so she wouldn’t have to work in the fields. You do your part, he told her. *Pass that exam! *

As she tried to focus on the textbook, Sona thought of the couplet from a Rabindranath Tagore poem that Sir, their primary-school teacher, had posted on the wall of his schoolroom. The Bangla words were embedded in her memory: Freedom from the insult of dwelling in a puppet’s world, where movements are started through brainless wires, repeated through mindless habits. Working on the plantation would feel like being trapped in a puppet’s world. She’d be locked behind brainless wires, trapped in a world of mindless habits. She had to keep that scholarship, no matter what it took!

There was enough daylight now to see without lighting a candle, but a Hindi song from next door kept crashing into the English words she was trying to memorise. The volume was loud because their neighbour’s mother was hard of hearing. A singer was belting out a song about eloping because they were in love.

Sona scowled. So many popular songs in India were about falling in love – like young couples did in the West. To her, the Nepali way seemed safer. Her parents and grandparents had been happy in their arranged marriages. Besides, all falling in love did was get people in trouble. Romance was why her brother had been falsely accused of stealing the motorcycle – their neighbour had caught his daughter with Samiran Daju at the cinema hall and wanted revenge. He’d shipped his daughter down to Kolkata to finish her schooling and still scowled at their family every time he saw them.

*Oh, Samiran Daju! Please don’t fall in love again! *She glanced out of the window, and this time caught sight of him cycling up the road. His shoulders were bowed as he dismounted and trudged to the house. She knew he’d stop to wash his hands and face with the bit of water she’d left outside for him.

“No luck today, Daju?” she asked as he came in.

He managed a smile. “Nothing. But seeing you hard at work inspires me. I’ll try again after breakfast.”

“Let’s eat quickly. I have to fetch water, remember?”

“I’ll cook like the wind. Keep studying.”

He cracked eggs open into the skillet and cooked them with the chillies, onions and garlic Sona had chopped. Singing along with the radio next door, he added the potatoes and stirred in salt, coriander, and turmeric.

Sona inhaled deeply. Mmmmmm … the smell of her brother’s cooking and the sound of his voice always made her relax.

“Feeling more hopeful?” Samiran Daju asked as they plopped down onto the mat to eat. “Wish I could help you with English, but you’ll have to teach me that crazy language once you’re fluent.”

She groaned. “I’m so scared I won’t pass. Why didn’t Sir teach us more English?”

Her brother took a big swig of water. “You know why. He wants the Nepali students to stay strong in our mother tongue. That’s one of the many reasons we respect him so much.” She agreed with Samiran Daju, of course, but frustration over her limited English pushed her to argue. “He’s not even Nepali himself! He’s Bengali!”

“He’s a Bengali who cares about non-Bengalis. Besides, you didn’t need him to teach you Bangla – you’re fluent in that already. That’s far ahead of most Nepali people in the state of West Bengal, including Ama and me.” He ladled the last helping of eggs and potatoes onto her plate. “There was a quote about learning languages on the schoolroom wall that made me think of you when Sir explained it. Do you remember it?”

Sona knew which one he meant; this one was in English. She’d memorised dozens of quotes Sir had posted, whether in Nepali, English, Bangla or Hindi. “‘With languages, you are at home anywhere’ by Edmund De Waal,” she said.

“Translate into Nepali for me, please. It’s good practice for you.” He listened as she chose the right words in their own language. “Yes! That’s what you do in every language – make yourself at home anywhere, with anyone, and make them feel at home, too. Bahini, god gave you a kind heart and a keen brain. Look how beautifully you translated that quote from English. You’ll pass that exam – I know you will.”

Sona couldn’t help smiling. Bahini meant “little sister” in their mother tongue, and it always sounded sweet to her ears. Like their father before him, her big brother saw her as practically perfect. Sometimes, though, that felt like a lot to live up to.

She sighed. “I’ll keep trying. You have enough money for this month’s payment to Banerji babu, right?”

Her brother dropped his eyes to his plate. “Not yet. I only worked five days this month. On top of that, I had to replace a tyre on my cycle and Ama needed a new skillet, plus we had to pay for bottled water– we’re short on cash.”

Sona’s stomach twisted. “Oh, Samiran Daju! No! I can’t stand the thought of that Bengali big shot making you beg for grace.”

“I won’t beg,” Samiran Daju said, lifting his head. “I’ll make that payment; I promise. I have a plan. You’ve always trusted me, bahini. Don’t stop now.”

Sona managed a smile. She did trust Samiran Daju, even if she worried. He’d keep his promise. He always did. In the meantime, she had to master English. And for that, she needed to visit her friend Tara Banerji, niece of the “Bengali big shot”.

But first things first: water.

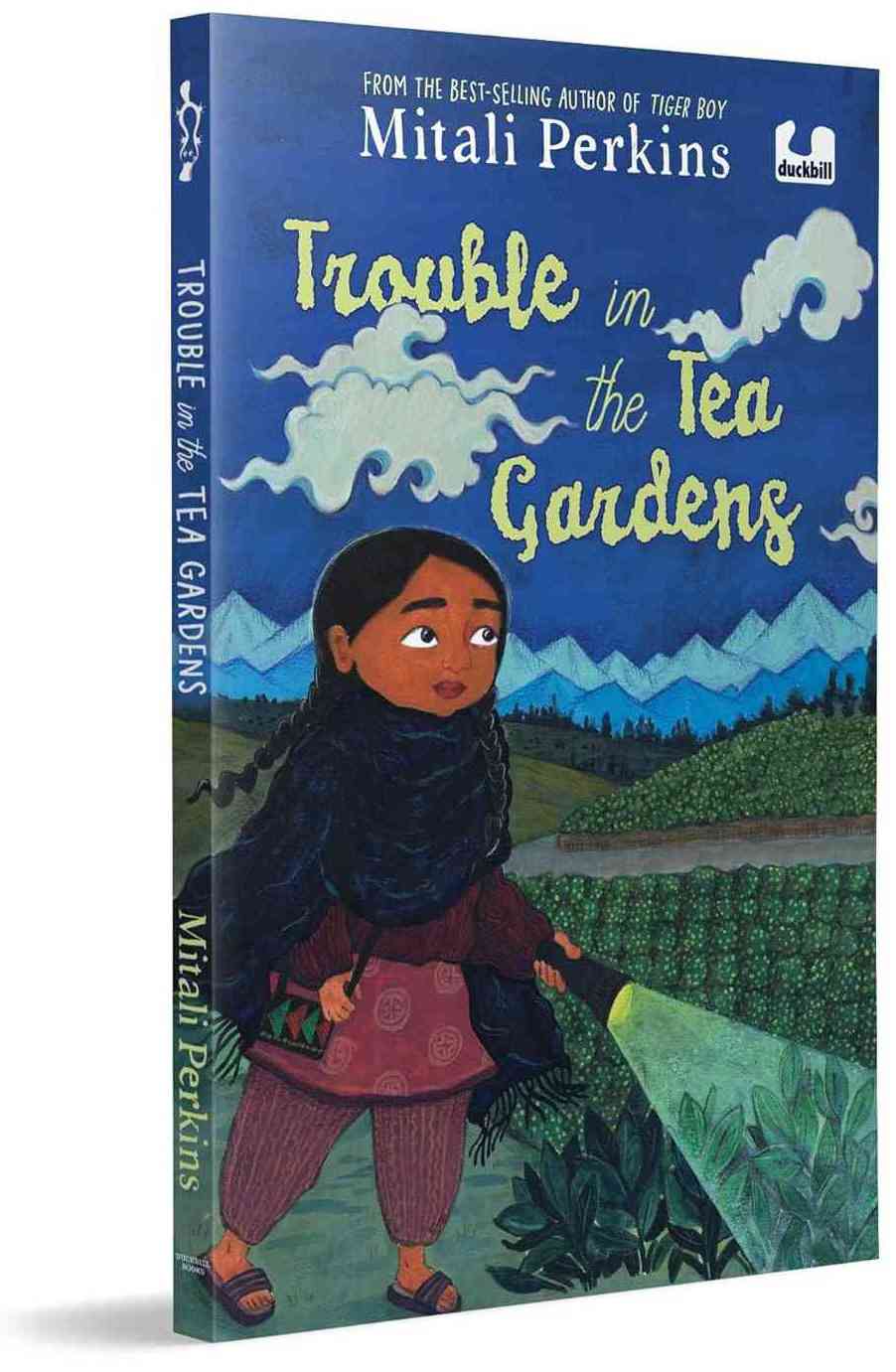

*Excerpted with permission from *Trouble in the Tea Gardens, Mitali Perkins, illustrated by Tanvi Bhat, Duckbill.

- We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in. *

Get the app