Game changing editions

Written on 2025-11-13

A couple of weeks ago, I shared my wishlist for PHP in 2026, and the one item that stood out were “PHP Editions”. Let’s unpack why I think this would be a gamechanger for PHP.

What are editions?

The word “edition” was pitched by Nikita Popov years ago, and was inspired by Rust editions. They are a way to evolve a language without being blocked by (as many) backwards compatibility issues:

There are times when it’s useful to make backwards-incompatible changes to the language […] Rust uses editions to solve this problem. When there are backwards-incompatible changes, they are pushed into the next edition. Sin…

Game changing editions

Written on 2025-11-13

A couple of weeks ago, I shared my wishlist for PHP in 2026, and the one item that stood out were “PHP Editions”. Let’s unpack why I think this would be a gamechanger for PHP.

What are editions?

The word “edition” was pitched by Nikita Popov years ago, and was inspired by Rust editions. They are a way to evolve a language without being blocked by (as many) backwards compatibility issues:

There are times when it’s useful to make backwards-incompatible changes to the language […] Rust uses editions to solve this problem. When there are backwards-incompatible changes, they are pushed into the next edition. Since editions are opt-in, existing crates won’t use the changes unless they explicitly migrate into the new edition.

In other words: editions allow us to have opt-in breaking changes.

In Rust, you specify the edition in a Cargo.toml file (similar to composer.json):

[package]

name = "Tempest"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

Every package in Rust can thus define its own edition, and different packages within the same projects can use other editions, all working together. There is a lot to unpack about editions, some parts translate easily to PHP while others don’t. In this post, I’ll go through everything step by step. First, let’s talk about why opt-in breaking changes have a lot of potential, then let’s talk about the different ways they could be implemented in PHP.

Why break stuff?

“Can’t we just… not break stuff?” Sure, PHP already does its utmost best to keep backwards compatibility to the highest level. That doesn’t always work out, and luckily, there are automated tools these days that have made upgrading PHP super easy. Despite all of that, Packagist stats report around 50% of PHP projects running on outdated versions. Around 50% of the most popular open source packages still support outdated PHP versions as well. Last year, PHP increased their security support for outdated versions with an additional year, creating even less incentive for projects to upgrade.

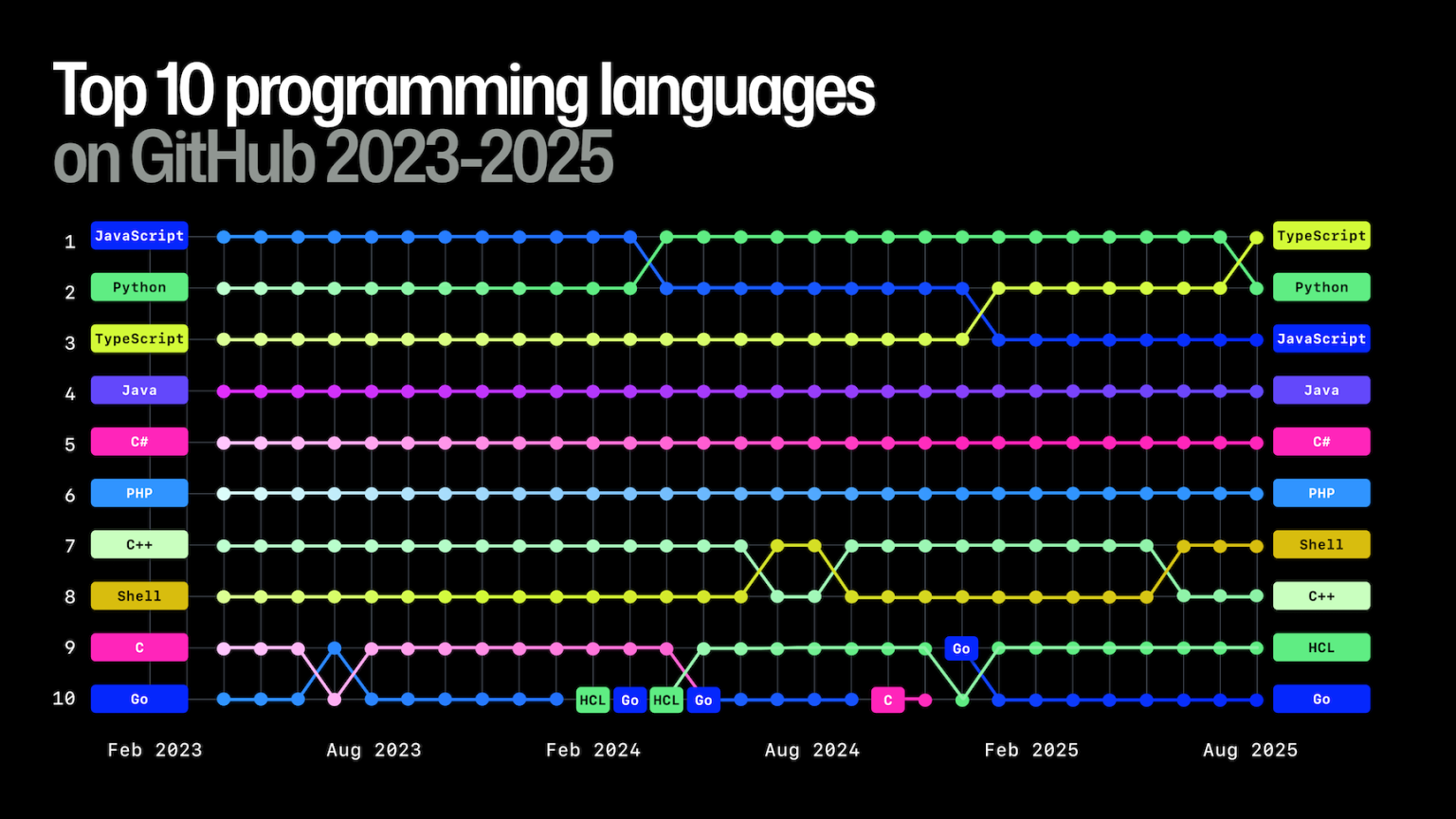

PHP doesn’t hold on to backwards compatibility just for the sake of it. It does indeed bring stability to the ecosystem. PHP’s backwards compatibility promise has made the language a reliable and trusted choice. For example, the recent state of GitHub in 2025 shows that PHP has been a steady programming language for years:

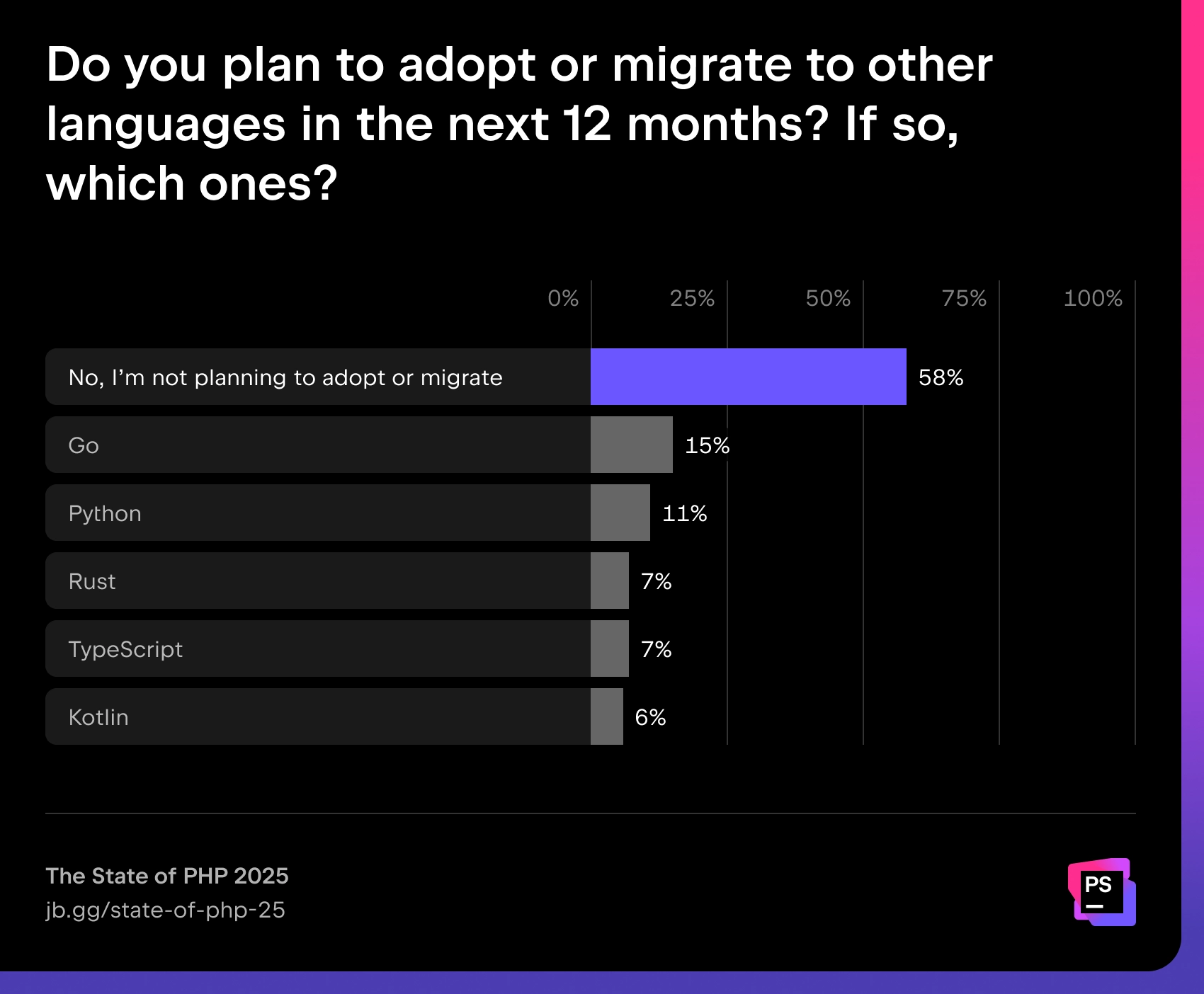

Stability comes at a cost, though. It’s getting increasingly difficult to evolve PHP and shape it into a more modern language. Expectations of a programming language in 2025 are different from those in 2000, and PHP is struggling to keep up. JetBrains’ recent dev ecosystem survey, for example, shows that a large portion of surveyed developers consider adopting languages like Go, Python, or Rust, alongside or instead of PHP. I don’t think that in itself is bad: using different technologies for different tasks has its merits; but it also shows that there is room for PHP to grow.

Here’s a powerful insight that Nikita Popov shared on the matter when he was still working on PHP:

I think that introducing this kind of concept [editions] for PHP is very, very important. We have a long list of issues that we cannot address due to backwards compatibility constraints and will never be able to address, on any timescale, without having the ability of opt-in migration.

So, why do we need to “break stuff”? I would summarize it as this: to move the language forward in a relevant, contemporary way, at a reasonable timescale.

A long list of issues

Before diving into technicalities, let’s also unpack what Nikita meant with “a long list of issues that currently can’t be addressed”. Let’s make sure we know what we’re talking about in practice. Here are a couple of ideas that Nikita listed when he was still working on PHP:

- Explicit pass-by-reference, where both the call-site and definition-site have to define references. You can read more about it here.

- Strict operators, which makes all operators use strict comparisons. There’s also an RFC for it.

- Improved string interpolation to allow arbitrary expressions like

$string = "foo #{1 + 1} bar". You can read about it here. - Finally, Nikita’s list mentioned a feature that has since been implemented without editions: the deprecation of dynamic properties.

That last one, actually, is interesting. Indeed, dynamic properties were deprecated in PHP 8.2, and might be removed in PHP 9.0 (although that has yet to be confirmed). To deal with the deprecation and potential future-breaking change, we got a new #[AllowDynamicProperties] attribute: a way to opt-out of the deprecation, on a class-based level. With this new attribute, though, we have essentially added another thing that has to be deprecated and removed before dynamic properties can be entirely gone from the language. That’s because, technically, you could consider the removal of #[AllowDynamicProperties] to be a breaking change in itself as well. As far as I know, there’s no consensus yet on how to deal with this change, but you can see how the addition of the attribute is causing a lot of headaches.

Let’s imagine how the deprecation of dynamic properties could have gone if we had opt-in breaking changes: the #[AllowDynamicProperties] attribute wouldn’t have been necessary, since people would have been able to opt-in the breaking change on their own basis. Whatever vendor dependencies still relied on dynamic properties could have decided to not support this feature (yet), and everything would have been worked without even the need for deprecation.

Those were Nikita’s examples, I can think of a couple more features that would made sense to be opt-in as well:

- Disabling the runtime type checker for parts of your code that’s being verified by static analyzer, possibly increasing runtime performance.

- Building on top of that, if “running PHP without runtime type checks” becomes acceptable, this would finally open the door for proper generics support.

- New features could be marked as “experimental opt-ins”: features that we’re sure will end up in the language, but might need another year of real-life testing and fine-tuning before calling them “stable”.

You might disagree with some of the proposals listed above, and that’s ok. These are just here as examples to show how opt-in breaking changes could help PHP move forward. Now that we know what kind of things could be possible, let’s discuss the technical side.

Editions — or something else?

You might have noticed that I tried to avoid the word “edition” and preferred to use “opt-in breaking changes” instead. That’s because I don’t think PHP should port the concept of editions as we know it in Rust and call it a day. For starters, Rust editions all compile to the same version. While that’s trivial to do in Rust, I reckon it would be a lot more tricky to pull off in PHP, due to its runtime nature. It also limits the scope of things that can be “editioned”. On top of that, Rust editions also come with a “lifetime guarantee”, something that I’m not sure is the best approach for PHP either.

When you get to the core of “editions”, though, it’s about opt-in breaking changes. That, I think, is key to helping PHP move into the next phase of maturity.

The best part? We already have a mechanism in place that allows opt-in breaking changes! It’s been in PHP since PHP 4. We’ve barely tapped its potential, but the foundation is already there. I’m talking about declare.

Declare has been in PHP since virtually forever, but you probably only know it because the addition of scalar types in PHP 7, which also came with the opt-in declare(strict_types=1) directive. It’s a way to optionally change PHP’s type checker behavior to be more strict to accommodate these newly added type hints. This is a perfect example of an opt-in breaking change: by default, PHP keeps working like normal, except for files that explicitly declare they want to use the stricter type checker.

Now, there are some limitations to how the strict_types specificially were implemented, and I don’t want to dive deep into those, because it would lead us too far into a slightly unrelated rabbit hole. The main takeaway for me is that we already have a mechanism in place that allows for opt-in breaking changes, and that mechanism only needs a minor change to become truly useful.

Namespace-scoped declares

The one downside of declare directives is how they are defined on a file-based level. Indeed, they provide a lot of granularity for toggling features on and off per file; but having to add declare(strict_types=1) on every file becomes tedious very fast. Now imagine adding more opt-in flags, and you’ll soon end up with a total mess:

<?php

declare(strict_types=1);

declare(strict_operators=1);

declare(runtime_type_checks=0);

declare(generics=1);

Keep in mind: this would have to be repeated for every single PHP file you want to opt-into breaking changes.

No, declare in its current state isn’t a viable solution, but it would only require a minor new feature to unlock its full potential: the ability to declare directives on a namespace level. And guess what? Nikita was already working on this mechanism when he was still actively involved in PHP! There’s an RFC for it, as well as a pull request with initial implementation!

All of this work stopped when Nikita left PHP, but from what I can tell, it shouldn’t be too difficult bringing this RFC back to the table. If it were to succeed, we’d be able to write something like this:

namespace_declare('Tempest\\', [

'strict_types' => 1,

'strict_operators' => 1,

'runtime_type_checks' => 0,

'generics' => 0,

]);

Even better, I reckon it would be trivial for composer to add support for namespace-scoped declares, which I believe would be the recommended way to configure them, similar to how composer wraps PHP’s class autoloading:

{

"autoload": {

"psr-4": {

"Tempest\\": "src/"

}

},

"declare": {

"Tempest\\": {

"strict_types": "1",

"strict_operators": "1",

"runtime_type_checks": "0",

"generics": "0",

}

}

}

Having read through Nikita’s draft work from years ago, I think we’re only one minor RFC away from unlocking a whole new potential for PHP.

Unanswered questions

I’m skipping over a lot of intricacies and details. For example, the main discussion topic was whether PHP should have a concept of editions like Rust, or build on top of the existing declare directive. The Rust approach would mean we’d have one edition per year at max, and each edition would build on top of the other. Embracing declare would mean more flexibility, but also more complexity.

On top of that, there are questions like:

- Do we support opt-in breaking changes indefinitely, like Rust, or will we have true “breaking-points” where opt-in features become the default in a new major version?

- The idea of experimental features could be massively beneficial to PHP as well, but I only mentioned it briefly, and there are a lot of details to be discussed there.

- What kind of changes could be modeled as opt-ins? Some things might be technically too complex to pull off or run into other kinds of limitations.

I’ve skimmed over my personal preference in this blog post, and I’m happy to further elaborate on it soon. At the same time, let’s take it step by step: whether we choose to go with yearly editions or granular feature toggles, we’ll need namespaced-scoped declares in both cases. Even if neither approaches got accepted, we would still benefit from namespace-scoped declares today because of strict_types, which we could then define on a higher level.

My plan is to not just blog about it. I had to write this blog post to order my thoughts, and my next step is to talk to some Foundation members and gather their input. I’m up for helping revive the namespace-scoped declares, as well as help carve out a framework for what “opt-in features” in PHP would look like in the future.

I would also like to hear from you: I’m especially curious to hear your thoughts about linear editions vs. granular feature opt-ins. You can leave your thoughts in the comments, send me an email, or join the Tempest Discord server.