OpenAI’s flood of announcements are getting hard to keep up with. A selection — not exhaustive! — from just the last month:

- A massive data center buildout in partnership with Oracle

- A $100 billion investment from Nvidia and associated deal to acquire 10 GW worth of Nvidia chips

- A new Instant Checkout offering for the long tail of e-commerce

- A partnership with Samsung and SK hynix for memory for AI chips

- The Sora 2 video generation model and [Sora the app](https://stratechery.c…

OpenAI’s flood of announcements are getting hard to keep up with. A selection — not exhaustive! — from just the last month:

- A massive data center buildout in partnership with Oracle

- A $100 billion investment from Nvidia and associated deal to acquire 10 GW worth of Nvidia chips

- A new Instant Checkout offering for the long tail of e-commerce

- A partnership with Samsung and SK hynix for memory for AI chips

- The Sora 2 video generation model and Sora the app

- A deal with AMD for 6 GW worth of AMD chips and an associated OpenAI stake in the chipmaker

- A slew of DevDay announcements, including apps in ChatGPT, AgentKit, Sora 2 and GPT-5 Pro in the API, the GA release of Codex, and more. The last two announcements just dropped yesterday, and actually bring clarity and coherence to the entire list. In short, OpenAI is making a play to be the Windows of AI.

For nearly two decades smartphones, and in particular iOS, have been the touchstones in terms of discussing platforms. It’s important to note, however, that while Apple’s strategy of integrating hardware and software was immensely profitable, it entailed leaving the door open for a competing platform to emerge. The challenge of being a hardware company is that by virtue of needing to actually create devices you can’t serve everyone; Apple in particular didn’t have the capacity or desire to go downmarket, which created the opportunity for Android to not only establish a competing platform but to actually significantly exceed iOS in market share.

For nearly two decades smartphones, and in particular iOS, have been the touchstones in terms of discussing platforms. It’s important to note, however, that while Apple’s strategy of integrating hardware and software was immensely profitable, it entailed leaving the door open for a competing platform to emerge. The challenge of being a hardware company is that by virtue of needing to actually create devices you can’t serve everyone; Apple in particular didn’t have the capacity or desire to go downmarket, which created the opportunity for Android to not only establish a competing platform but to actually significantly exceed iOS in market share.

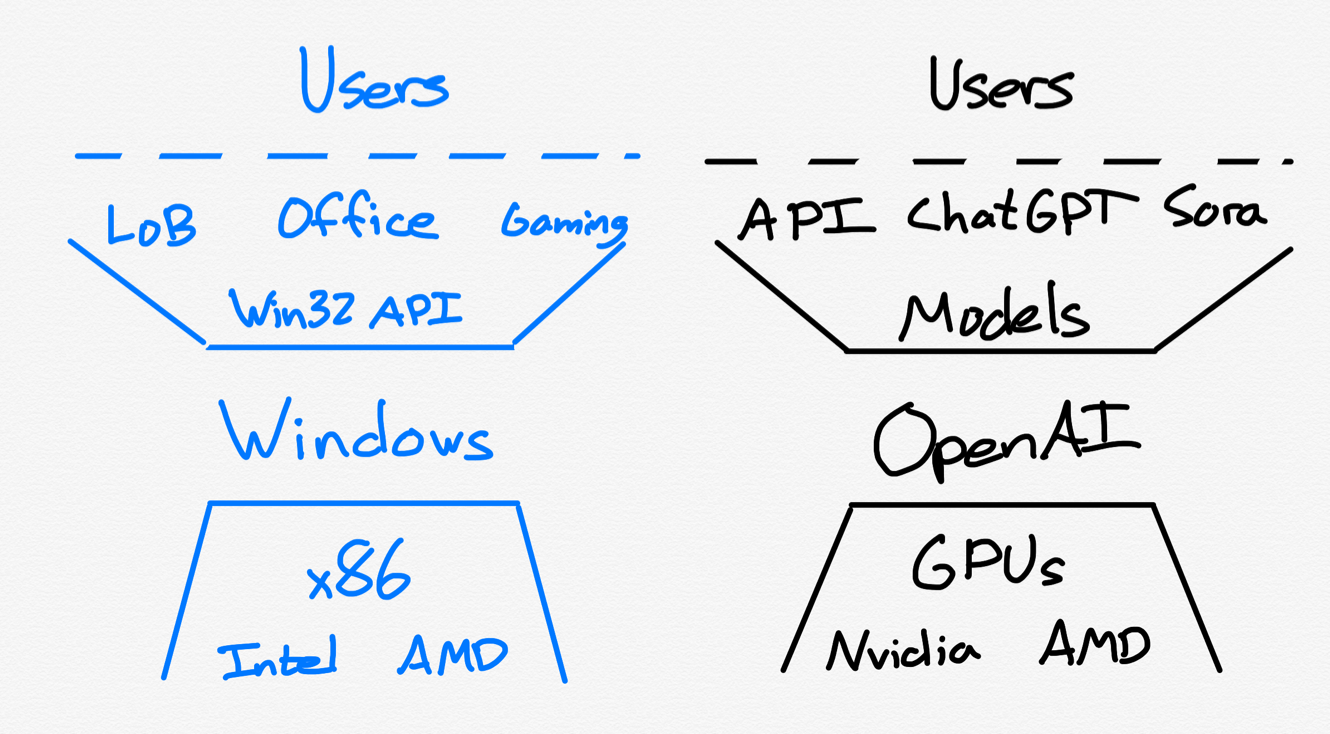

That means that if we want a historical analogy for total platform dominance — which increasingly appears to be OpenAI’s goal — we have to go back further to the PC era and Windows.

Platform Establishment

Before there was Windows there was DOS; before DOS, however, there was a fast-talking deal-making entrepreneur named Bill Gates. From The Truth About Windows Versus the Mac:

In the late 1970s and very early 1980s, a new breed of personal computers were appearing on the scene, including the Commodore, MITS Altair, Apple II, and more. Some employees were bringing them into the workplace, which major corporations found unacceptable, so IT departments asked IBM for something similar. After all, “No one ever got fired for buying IBM.”

IBM spun up a separate team in Florida to put together something they could sell IT departments. Pressed for time, the Florida team put together a minicomputer using mostly off-the shelf components; IBM’s RISC processors and the OS they had under development were technically superior, but Intel had a CISC processor for sale immediately, and a new company called Microsoft said their OS — DOS, which they acquired from another company — could be ready in six months. For the sake of expediency, IBM decided to go with Intel and Microsoft.

The rest, as they say, is history. The demand from corporations for IBM PCs was overwhelming, and DOS — and applications written for it — became entrenched. By the time the Mac appeared in 1984, the die had long since been cast. Ultimately, it would take Microsoft a decade to approach the Mac’s ease-of-use, but Windows’ DOS underpinnings and associated application library meant the Microsoft position was secure regardless.

There is nothing like IBM and its dominant position in enterprise today; rather, the route to becoming a platform is to first be a massively popular product. Acquiring developers and users is not a chicken-and-egg problem: it is clear that you must get users first, which attracts developers, enhancing your platform in a virtuous cycle; to put it another way, first a product must Aggregate users and then it gets developers for free.

ChatGPT is exactly that sort of product, and at yesterday’s DevDay 2025 keynote CEO Sam Altman and team demonstrated exactly that sort of pull; from The Verge:

OpenAI is introducing a way to work with apps right inside ChatGPT. The idea is that, from within a conversation with the chatbot, you can essentially tag in apps to help you complete a task while ChatGPT offers context and advice. The company showed off a few different ways this can work. In a live demo, an OpenAI employee launched ChatGPT and then asked Canva to create a poster of a name for a dog-walking business; after a bit of waiting, Canva came back with a few different examples, and the presenter followed up by asking for a generated pitch deck based on the poster. The employee also asked Zillow via ChatGPT to show homes for sale in Pittsburgh, and it created an interactive Zillow map — which the employee then asked follow-up questions about.

Apps available inside ChatGPT starting today will include Booking.com, Canva, Coursera, Expedia, Figma, Spotify, and Zillow. In the “weeks ahead,” OpenAI will add more apps, such as DoorDash, OpenTable, Target, and Uber. OpenAI recently started allowing ChatGPT users to make purchases on Etsy through the chatbot, part of its overall push to integrate it with the rest of the web.

It’s fair to wonder if these app experiences will measure up to these company’s self-built apps or websites, just as there are questions about just how well the company’s Instant Checkout will convert; what is notable, however, is that I disagree that this represents a “push to integrate…with the rest of the web”.

This is the opposite: this is a push to make ChatGPT the operating system of the future. Apps won’t be on your phone or in a browser; they’ll be in ChatGPT, and if they aren’t, they simply will not exist for ChatGPT users. That, by extension, means the burden of making these integrations work — and those conversions performant — will be on third party developers, not OpenAI. This is the power that comes from owning users, and OpenAI is flexing that power in a major way.

Second Sourcing

There is a second aspect to the IBM PC strategy, and that is the role of AMD. From a 2024 Update:

While IBM chose Intel to provide the PC’s processor, they were wary of being reliant on a single supplier (it’s notable that IBM didn’t demand the same of the operating system, which was probably a combination of not fully appreciating operating systems as a point of integration and lock-in for 3rd-party software, which barely existed at that point, and a recognition that software is just bits and not a physical good that has to be manufactured). To that end IBM demanded that Intel license its processor to another chip firm, and AMD was the obvious choice: the firm was founded by Jerry Sanders, a Fairchild Semiconductor alum who had worked with Intel’s founders, and specialized in manufacturing licensed chips.

The relationship between Intel and AMD ended up being incredibly fraught and largely documented by endless lawsuits (you can read a brief history in that Update); the key point to understand, however, is that (1) IBM wanted to have dual suppliers to avoid being captive to an essential component provider and (2) IBM had the power to make that happen because they had the customers who were going to provide Intel so much volume.

The true beneficiary of IBM’s foresight, of course, was Microsoft, which controlled the operating system; IBM’s mandate is why it is appropriate that “Windows” comes first in the “Wintel” characterization of the PC era. Intel reaped tremendous profits from its position in the PC value chain, but more value accrued to Microsoft than anyone else.

This question of who will capture the most profit from the AI value chain remains an open one. There’s no question that the early winner is Nvidia: the company has become the most valuable in the world by virtue of its combination of best-in-class GPUs, superior networking, and CUDA software layer that locks people into Nvidia’s own platform. And, as long as power is the limiting factor, Nvidia is well-placed to maintain its position.

What Nvidia is not shy about is capturing its share of value, and that is a powerful incentive for other companies in the value chain to look for alternatives. Google is the furthest along in this regard thanks to its decade-old investment in TPUs, while Amazon is seeking to mimic their strategy with Trainium; Microsoft and Meta are both working to design and build their own chips, and Apple is upscaling Apple Silicon for use in the data center.

Once again, however, the most obvious and most immediately available alternative to Nvidia is AMD, and I think the parallels between yesterday’s announcement of an OpenAI-AMD deal and IBM’s strong-arming of Intel are very clear; from the Wall Street Journal:

OpenAI and chip-designer Advanced Micro Devices announced a multibillion-dollar partnership to collaborate on AI data centers that will run on AMD processors, one of the most direct challenges yet to industry leader Nvidia. Under the terms of the deal, OpenAI committed to purchasing 6 gigawatts worth of AMD’s chips, starting with the MI450 chip next year. The ChatGPT maker will buy the chips either directly or through its cloud computing partners.

AMD chief Lisa Su said in an interview Sunday that the deal would result in tens of billions of dollars in new revenue for the chip company over the next half-decade. The two companies didn’t disclose the plan’s expected overall cost, but AMD said it costs tens of billions of dollars per gigawatt of computing capacity. OpenAI will receive warrants for up to 160 million AMD shares, roughly 10% of the chip company, at 1 cent per share, awarded in phases, if OpenAI hits certain milestones for deployment. AMD’s stock price also has to increase for the warrants to be exercised.

If OpenAI is the software layer that matters to the ecosystem, then Nvidia’s long-term pricing power will be diminished; the company, like Intel, may still take the lion’s share of chip profits through sheer performance and low-level lock-in, but I believe the most important reason OpenAI is making this deal is to lock in its own dominant position in the stack. It is pretty notable that this announcement comes only weeks after Nvidia’s investment in OpenAI; that, though, is another affirmation that the company who has the users has the ultimate power.

There is one other part of the stack to keep an eye on: TSMC. Both Nvidia and AMD make their chips with the Taiwanese giant, and while TSMC is famously reticent to take price, they are positioned to do so in the long run. Altman surely knows this as well, which means that I wouldn’t be surprised if there is an Intel announcement sooner rather than later; maybe there is fire to that recent smoke about AMD talking with Intel?

The AI Linchpin

When I started writing Stratechery, Windows was a platform in decline, superceded by mobile and, surprisingly enough, increasingly challenged by its all-but-vanquished ancient foe, the Mac. To that end, one of my first pieces about Microsoft was about then-CEO Steve Ballmer’s misguided attempt to focus on devices instead of services. I wrote a few years later in Microsoft’s Monopoly Hangover:

The truth is that both [IBM and Microsoft] were victims of their own monopolistic success: Windows, like the System/360 before it, was a platform that enabled Microsoft to make money in all directions. Both companies made money on the device itself and by selling many of the most important apps (and in the case of Microsoft, back-room services) that ran on it. There was no need to distinguish between a vertical strategy, in which apps and services served to differentiate the device, or a horizontal one, in which the device served to provide access to apps and services. When you are a monopoly, the answer to strategic choices can always be “Yes.”

Microsoft at that point in time no longer had that luxury: the company needed to make a choice — the days of doing everything were over — and that choice should be services (which is exactly what Satya Nadella did).

Ever since the emergence of ChatGPT made OpenAI The Accidental Consumer Tech Company I have been making similar arguments about OpenAI: they need to focus on the consumer opportunity and leave the enterprise API market to Microsoft. Not only would focus help the company capture the consumer opportunity, there was the opportunity cost of GPUs used for the API that couldn’t be used to deliver consumers a better experience across every tier.

I now have much more appreciation for OpenAI’s insistence on doing it all, for two reasons. First, this is a company in pure growth mode, not in decline. Tradeoffs are in the long run inevitable, but why make them before you need to? It would have been a mistake for Microsoft to restrict Windows to only the enterprise in the 1980s, even if the company had to low-key retreat from the consumer market over the last fifteen years; there was a lot of money to make before that retreat needed to happen! OpenAI, meanwhile, is the hottest brand in AI, so why not make a play to own it all, from consumer touchpoint to API to everything in-between?

Second, we’ve obviously crossed the line into bubble territory, which always was inevitable. The question now is whether or not this is a productive bubble: what durable infrastructure will be built by eventually bankrupt companies that we benefit from for years to come?

GPUs are not that durable infrastructure; data centers are more long-lasting, but not worth the financial pain of a bubble burst. The real payoff would be a massive build-out in power generation, which would be a benefit for the next half a century. Another potential payoff would be the renewed viability of Intel, and as I noted above, OpenAI may be uniquely positioned and motivated to make that happen.

More broadly, this play to be the Windows of AI effectively positions OpenAI as the linchpin of the entire AI buildout. Just look at what the mere announcement of partnerships with OpenAI has done for the stocks of Oracle and AMD. OpenAI is creating the conditions such that it is the primary manifestation of the AI bubble, which ensures the company is the primary beneficiary of all of the speculative capital flooding into the space. Were the company more focused, as I have previously advised, they may not have the leverage to get enough funding to meet those more modest (but still incredible) goals; now it’s hard to see them not getting whatever money they want, at least until the bubble bursts.

What’s amazing about this overview is that I only scratched the surface of what OpenAI announced both yesterday and over the last month — and I haven’t even mentioned Sora (although I covered that topic yesterday). What the company is seeking to achieve is incredibly audacious, but also logical, and something we’ve seen before:

And, interestingly enough, there is an Apple to OpenAI’s Microsoft: it’s Google, with their fully integrated stack, from chips to data centers to models to end user distribution channels. Instead of taking on a menagerie of competitors, however, Google is facing an increasingly unified ecosystem, organized, whether they wish to be or not, around OpenAI. Such is the power of aggregating demand and the phenomenon that is ChatGPT.

And, interestingly enough, there is an Apple to OpenAI’s Microsoft: it’s Google, with their fully integrated stack, from chips to data centers to models to end user distribution channels. Instead of taking on a menagerie of competitors, however, Google is facing an increasingly unified ecosystem, organized, whether they wish to be or not, around OpenAI. Such is the power of aggregating demand and the phenomenon that is ChatGPT.