The Chemainus River reveals its secrets in strange and unexpected ways.

For years, I have wandered the forests near my North Cowichan home in search of the last few ancient trees, finding a few nice specimens here and there, but nothing I could describe as old growth.

In the heavily logged, 5,000-hectare Municipal Forest Reserve — popularly known as the Six Mountains, an hour north of Victoria — they are as elusive as the last rhinos of Sumatra. With a bit of luck, I hope my persistence may yet pay off.

I don’t know it at the time, but my quest will launch me on a journey from the river’s headwaters to its mouth in pursuit of questions fundamental to the Chemainus and its future.

How have human activities like industrial logging shaped the river, its watershed, and its salmon?

Wh…

The Chemainus River reveals its secrets in strange and unexpected ways.

For years, I have wandered the forests near my North Cowichan home in search of the last few ancient trees, finding a few nice specimens here and there, but nothing I could describe as old growth.

In the heavily logged, 5,000-hectare Municipal Forest Reserve — popularly known as the Six Mountains, an hour north of Victoria — they are as elusive as the last rhinos of Sumatra. With a bit of luck, I hope my persistence may yet pay off.

I don’t know it at the time, but my quest will launch me on a journey from the river’s headwaters to its mouth in pursuit of questions fundamental to the Chemainus and its future.

How have human activities like industrial logging shaped the river, its watershed, and its salmon?

What role might climate change play in the watershed’s future?

What is being done to protect the Chemainus?

In my search for answers, I will discover modern challenges that bedevil other B.C. coastal rivers.

And in the waters of the Chemainus, I will find what makes one oft-overlooked river worthy of the appreciation that often eludes it.

Video by Larry Pynn.

1. In Search of a Giant

Two years ago my explorations lead me improbably to an old clearcut above the Chemainus River. There is no river to be seen, no roar of rushing water, and no obvious reason to be here. But a previous investigation of LiDAR topography and vegetation maps suggests that big trees are somewhere below us in the distance.

My friend Bruce Coates, the president of Nature Cowichan, a local conservation and education non-profit, accompanies me through a stunted landscape that once grew giants in a coastal Douglas fir forest, the smallest and rarest of B.C.’s 16 biogeoclimatic zones.

We drive down a logging spur road, then walk past the scattered bones of black-tailed deer dumped by hunters in a no-shooting zone. The roadside is littered with household garbage: stove pipes, concrete blocks, clothes, plastic toys, and a four-slice toaster. Nearby sits the shell of a fibreglass boat, its outboard engine removed.

We follow rainwater trickling like mercury down a slick, narrowing route and soon leave the vulgarities of humanity behind.

A vantage point finally allows us to view the Chemainus River hurrying behind a veil of moss-smothered trees — western red cedar, Douglas fir, grand fir, bigleaf maple, red alder and western hemlock.

The road ends at a small sandy beach that shows no sign of humans. No illegal campfires, no shotgun shells, no mounds of booze containers. None of the detritus found in other parts of the forest reserve that are accessible to motor vehicles.

The river’s current bounces off a shale cliff and forms rambunctious rapids downstream. The presence of whole trees stacked on gravel bars suggests the Chemainus has a temper that is best not ignored.

The Chemainus River winds through mountainous, rocky terrain en route to the Pacific Ocean. Photo by Larry Pynn.

We follow a thin trail upriver and, as we peel back sword ferns and flourishing Oregon grape, find dark stumps left behind by long-gone loggers.

The Chemainus River winds through mountainous, rocky terrain en route to the Pacific Ocean. Photo by Larry Pynn.

We follow a thin trail upriver and, as we peel back sword ferns and flourishing Oregon grape, find dark stumps left behind by long-gone loggers.

There are large standing trees, too, but they fall short of old-growth — officially defined as those at least 250 years old, dating from around the time British explorer Captain James Cook made contact at Yuquot/Friendly Cove on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Suddenly, a silhouette emerges from the riverbank. Could it be?

We approach and the immensity of this single plant comes into focus.

At last. An honest-to-goodness, old-growth cedar — one that, having somehow avoided the logger’s saw in a past century, today rules over this pocket forest.

Writer Larry Pynn admires a towering old-growth cedar along the banks of the Chemainus. Photo by Bruce Coates.

“It gives me the shivers,” Coates says. “A beautiful tree, and still very healthy.”

Writer Larry Pynn admires a towering old-growth cedar along the banks of the Chemainus. Photo by Bruce Coates.

“It gives me the shivers,” Coates says. “A beautiful tree, and still very healthy.”

At the height of my chest, the tree’s diameter exceeds two metres, making it bigger than anything the municipal forester has encountered in the reserve.

We continue wandering the shoreline and find another half-dozen giants, including more cedars and a Douglas fir, all close to the same size.

Documenting these last big trees could represent a satisfying conclusion to my journey. Instead, the experience raises ever more questions.

To find answers, I must continue my exploration — across all the seasons, returning time and again — to see what other secrets this landscape holds, to learn how history has influenced the present, and to better appreciate the challenges ahead.

Lower Banon Creek Falls punctuates the Lower Chemainus River. On a river that is often hidden from public view, the spot is one of the more popular access points. Photo by Larry Pynn.

Lower Banon Creek Falls punctuates the Lower Chemainus River. On a river that is often hidden from public view, the spot is one of the more popular access points. Photo by Larry Pynn.

2. Beginnings

In many ways, the Chemainus is a forgotten river.

The river begins on the slopes of Mount Whymper, named after an artist, Frederick Whymper, who explored the area in 1864. The 1,539-metre peak is the ultimate source of a river that flows 64 kilometres to tidewater.

Despite its respectable size, the Chemainus has received a fraction of the interest of its larger cousin, the Cowichan River, a dozen kilometres to the south.

The Cowichan’s valley is laced with bicycle and hiking trails, and the river is frequented by sport anglers, Indigenous spear fishers, inner tubers, paddlers and swimmers. The combination of Cowichan Lake and a pulp mill’s weir regulates downstream flows, reducing the threat of flooding along the river’s banks.

In contrast, access to the upper Chemainus is limited and the lower part of the river valley offers relatively few recreational opportunities due to its private properties, Indigenous reserve lands, and marshy estuary.

The Chemainus River runs from the flanks of Mount Whymper to the eastern coast of Vancouver Island. Image by Tyler Olsen/Google Studio.

One of the main entry points, the 103-hectare Chemainus River Provincial Park, suffers from illegal activities, including shooting, off-road vehicles, and campfires.

The Chemainus River runs from the flanks of Mount Whymper to the eastern coast of Vancouver Island. Image by Tyler Olsen/Google Studio.

One of the main entry points, the 103-hectare Chemainus River Provincial Park, suffers from illegal activities, including shooting, off-road vehicles, and campfires.

The District of North Cowichan often restricts vehicle access in summer at a second entry point — a sandy beach near Banon Creek — due to wildfire concerns. But the municipality encourages hiking and cycling as ways to deter and report on criminal behaviour. The only lawlessness I discover during my visit is the steel carcass of a motor vehicle almost certainly stolen and dumped in the river in the distant past.

Although the Chemainus River itself has been largely overlooked, the trees that lined its shores and river valley have not. For more than a century, the valley — like other watersheds across Vancouver Island — has been intensively logged. British Columbia was proud not just of the scale of the resource operations, but of the individual trees that were routinely pulled from the valley.

The Chemainus’s watershed was home to some of the world’s most-impressive trees. One was logged and sent to England to celebrate BC’s centennial. Photo via UBC/MacMillan Bloedel fonds.

In 1958, MacMillan Bloedel’s Copper Canyon crews cut down a 371-year-old Douglas fir to be shipped to England as a flagpole to celebrate BC’s centennial and the 200th anniversary of the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. It took two trucks with log swivels positioned above the height of the cabs to transport the behemoth along winding logging roads. The Guinness Book of Records recognized the 225-foot-tall flag pole as the world’s tallest.

The Chemainus’s watershed was home to some of the world’s most-impressive trees. One was logged and sent to England to celebrate BC’s centennial. Photo via UBC/MacMillan Bloedel fonds.

In 1958, MacMillan Bloedel’s Copper Canyon crews cut down a 371-year-old Douglas fir to be shipped to England as a flagpole to celebrate BC’s centennial and the 200th anniversary of the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. It took two trucks with log swivels positioned above the height of the cabs to transport the behemoth along winding logging roads. The Guinness Book of Records recognized the 225-foot-tall flag pole as the world’s tallest.

These days, the forest giants have been replaced with plantations and vast clearcuts that gnaw their way down mountain sides to the valley floor — landscape changes that have year-round hydrological implications.

Logging and other forms of human disturbance can reduce the land’s ability to hold back rainwater in winter and retain moisture in the heat of summer. And human-caused climate change is magnifying those impacts.

Younes Alila, a professor of hydrology in the University of British Columbia’s forestry department, told me about the “transient snow zone,” where snow levels fluctuate throughout winter and where snowpacks can melt quickly in heavy rains.

On the B.C. coast, that zone typically ranges from 300 to 1,100 metres above sea level. But when an atmospheric river brings heavy rain and mild temperatures to Vancouver Island, snow as high as 2,000 metres can melt, intensifying the flood threat downstream.

“The frequency, severity and duration of these extremes — droughts, floods, landslides — are being accentuated as a result of changing climate superimposed with changing land use and land cover,” Alila said.

Video by Larry Pynn.

3. Whitewater

Access to the valley is limited not just by geography and circumstance, but by the company that controls most of the land in the upper watershed.

Unlike much of British Columbia, where private logging companies obtain licenses to extract timber from publicly owned land, most of the upper Chemainus is privately owned and controlled by timber giant Mosaic Forest Management. Mosaic only opens the upper watershed to the public within specific hours on weekends — the sort of restrictions that have driven frustrated backcountry enthusiasts to form a coalition to lobby for greater openness. Mosaic is expected to release a report in the fall that seeks to balance greater public access with issues such as wildfire risk, illegal dumping, and liability.

After my successful search for giant trees in the lower river, my curiosity naturally leads to these upper headwaters, where problems with the river are likely rooted.

Here, I also see the incredible forces with which a river can exert itself. Nowhere on the Chemainus is that more apparent than at Copper Canyon, where the bottom falls out of the river and frenzied, fomenting waters tumble sharply through a narrow gap in the landscape.

I have hiked many mountains in B.C. — a couple of them first recorded ascents — but have never felt comfortable looking straight down, be it from a sheer cliff or, in this case, a logging road bridge with no handrails. One wrong move here means almost certain death.

Yet some adventurers are drawn here specifically for the considerable challenges.

Experienced whitewater kayakers paddle the canyon at medium water levels (peak flows are too dangerous), tackling rapids with names like Powerhouse, Landslide and Flume.

“That section of the river is pretty special,” says Garrett Quinn, president of the Vancouver Island Whitewater Paddling Society. “People come from pretty far and wide looking to paddle it.”

But while the currents delight recreation enthusiasts, for fish, the canyon can form a natural impediment.

Three species of salmon – chinook, coho and chum — spawn in the lower river, but only steelhead are able to navigate beyond the turbulent canyon into the upper watershed.

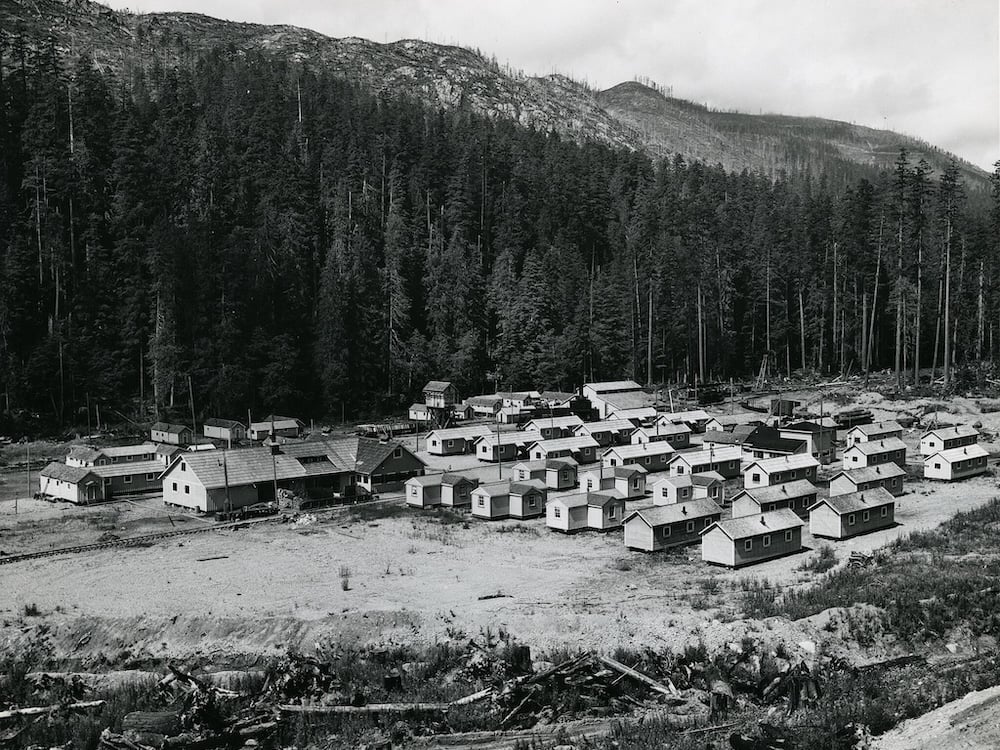

The Chemainus River has been a key logging centre for more than a century. In the MacMillan Bloedel camps housed crews tasked with bringing down trees. Photo via UBC Archives.

The Chemainus River has been a key logging centre for more than a century. In the MacMillan Bloedel camps housed crews tasked with bringing down trees. Photo via UBC Archives.

4. Ghosts of Industry

Humans have posed a far greater threat to the survival of the fish in the Chemainus than any rapid.

In the 1940s, fishermen illegally used dynamite to kill and harvest fish in Copper Canyon, according to a 1947 article in The Province. (The fishing method has been blackly described as the “C.I.L. wobbler,” after the former explosives company, Canadian Industries Ltd.)

Bomb-wielding fishermen were only one of several threats.

Logging activity in the area dates back to the 1800s, with significant impacts on the river’s fish habitats. The expansion of the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway around the turn of the century fed the industry’s growth and stoked environmental damage.

Railroads were carved into the river valley to expedite logging in the Chemainus area. Photo via UBC Archives.

Logging-fueled erosion and sedimentation also made it harder for salmon to successfully spawn.

Railroads were carved into the river valley to expedite logging in the Chemainus area. Photo via UBC Archives.

Logging-fueled erosion and sedimentation also made it harder for salmon to successfully spawn.

An Environment Canada report noted that chum returns plummeted from 60,000 to 9,350 between 1949 and 1968. Coho declined from 4,350 to just 348, and steelhead numbers also plunged, from 2,480 to 453.

“The drastic reduction in salmon escapements…is at least partially attributable to habitat disruption due to logging,” the report said.

The Chemainus River dodged a threat in the early 1970s when a proposed dam just above Copper Canyon was rejected because of concerns over its impact on fish, especially steelhead.

As the salmon disappeared, First Nation fisheries suffered around the region.

First Nations faced competition from commercial and sport-fishers, along with the ire of white communities who feared declining fish stocks and lost tourism revenue. Logging, meanwhile, continued to harm fish and their spawning habitat.

A 2001 book by UBC law professor Douglas C. Harris traced Indigenous peoples’ six-decade struggle to maintain their traditional weir fishery on the nearby Cowichan River through the late 1800s and into the 1930s.

“Loggers drove thousands of logs, millions of timber feet, down the river in the short period between the summer’s low water and the winter’s high water, the principal season of salmon migration,” Harris wrote in Fish, Law and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. “Log-jams were frequent, particularly in the canyons, and often required dynamiting. Once loosed, the logs and water swept down the river, threatening road and railway bridges, causing extensive damage to the riverbed, and killing the migrating salmon and trout.”

The salmon reliant on the Chemainus continue to feel the effects of a century of resource extraction. Photo by Larry Pynn.

Indigenous people ultimately lost the battle for their traditional weir fishery.

The salmon reliant on the Chemainus continue to feel the effects of a century of resource extraction. Photo by Larry Pynn.

Indigenous people ultimately lost the battle for their traditional weir fishery.

“The Cowichan built their last weir in 1936, a symbolic end of the last vestiges of Cowichan control,” Harris wrote. “They were confined to a meagre subsistence fishery, supervised by the state, on what had been their river.”

Today, pink salmon — the most plentiful salmon species across much of British Columbia — are no longer found in the river. A report in The Province in 1974 noted that a “fairly large run faded out in 1955.”

On the nearby Cowichan, salmon recovery is now a major focus of government and community efforts. It seems to be working. An estimated 25,914 adult chinook — the most prized salmon species — returned in 2024, the highest in at least 36 years.

But the plight of fish stocks on the Chemainus River has received relatively little public attention.

Summer chinook enter the river in spring and hole up in ever-shrinking pools until spawning in September and October.

The latest survey by four three-member teams working different sections of the river counted just five adults and two smaller jacks — among the lowest returns to date. That compares with a rough estimate of 3,000-4,000 winter chinook.

Each year, small teams wade and snorkel through low-lying parts of the Chemainus to survey salmon populations. Photo by Larry Pynn.

“It’s grim,” confirms biologist Damon Nowosad, with the Q’ul-lhanumutsun Aquatic Resources Society, which represents six Hul’q’umi’num’ communities in the Cowichan Valley region. “They’re not doing great, and they’re probably not talked about as much as they should.”

Each year, small teams wade and snorkel through low-lying parts of the Chemainus to survey salmon populations. Photo by Larry Pynn.

“It’s grim,” confirms biologist Damon Nowosad, with the Q’ul-lhanumutsun Aquatic Resources Society, which represents six Hul’q’umi’num’ communities in the Cowichan Valley region. “They’re not doing great, and they’re probably not talked about as much as they should.”

Cosmo Roemer, a biologist with Halalt First Nation, attributes the problem to the build-up of sediments due to the “cumulative effects of upper watershed timber harvest, agricultural land practices in the lower watershed, and urbanization.” Still, he is reluctant to point fingers, saying partnerships can yet be forged “to help us all move forward together in a good way.”

Clearcuts have been shown to increase run-off, aggravating droughts and the risk of landslides. Photo by Larry Pynn.

Clearcuts have been shown to increase run-off, aggravating droughts and the risk of landslides. Photo by Larry Pynn.

5. What Logging Has Done

The Chemainus is highly susceptible to flooding, a problem aggravated by logging.

Some of the worst inundations are caused by heavy winter rains and melting snow, a double whammy that may only be worsened by climate change. Raging flows tear trees from their banks, disgorge gravel and sediment, and pose a threat to people and properties downstream.

The situation is not unique to the Chemainus River.

A 2025 report by Vancouver geotechnical consultancy BGC Engineering counted 1,360 landslides across southern B.C. associated with the November 2021 atmospheric river. Nearly half occurred in areas that had seen logging and wildfires.

Hundreds of slides originated near logging roads and cutblocks. The report said that despite some improvement in forestry management practices, historic and ongoing resource extraction continue to increase the frequency of landslides.

Logging roads and poorly designed culverts are particularly problematic. They frequently lead to unstable slopes and unnatural drainage patterns that concentrate runoff and cause landslides, the report says.

But flooding is only half the problem.

“An increase in flood risk by clearcut logging always comes with the price of increasing drought risk,” UBC’s Alila said.

Clearcutting contributes to drought river conditions in various ways, including reducing forest shade necessary to slow the melt of snow in spring.

“We lose the temporary snowpack from the cut blocks down to the ocean several times in a flood season,” Alila said.

Forest hydrology professor Younes Alila warns that intensive logging reduces the ability of a forest to retain moisture. Photo submitted.

Forests also suck up moisture from the soil for photosynthesis and growth. That allows the soil to better absorb moisture during heavy rains. Furthermore, in mountainous terrain, logging roads are ditched and drained by culverts, which rob the landscape of moisture and accelerate runoff downstream.

Forest hydrology professor Younes Alila warns that intensive logging reduces the ability of a forest to retain moisture. Photo submitted.

Forests also suck up moisture from the soil for photosynthesis and growth. That allows the soil to better absorb moisture during heavy rains. Furthermore, in mountainous terrain, logging roads are ditched and drained by culverts, which rob the landscape of moisture and accelerate runoff downstream.

“If we did not log, the slow melt would recharge the groundwater, which comes in handy feeding streams during the driest period of the year in summer and early fall before the rain season starts again,” Alila said.

I have seen the raging Chemainus reduced to a whimper in summer. I once waded into a boulder-strewn section to retrieve my crashed drone mid-stream, barely getting my calves wet. At such times, the lack of water poses an obvious threat to fish. The Halalt frequently launch rescue missions to relocate juvenile fish stranded in warm, shallow isolated pools.

Biologists wearing wetsuits, masks and snorkels also float down the river from Copper Canyon to the estuary, counting chinook that have returned to spawn. Or at least that’s the idea. The day I watched from ashore, upstream of the Trans Canada Highway, the team wound up walking much of the distance due to scarcity of water.

The Chemainus River severely flooded Halalt First Nation territory after a heavy rainfall on Jan 31, 2020. Photo by Shawn Wagar.

The Chemainus River severely flooded Halalt First Nation territory after a heavy rainfall on Jan 31, 2020. Photo by Shawn Wagar.

6. A First Nations Lawsuit

Recent years have brought new efforts to help restore the Chemainus and its watershed. They have also brought new questions about how the area is managed and its consequences on local Indigenous people.

In 2024, Halalt First Nation, whose reserve sits near the river’s mouth, launched a class-action lawsuit against Mosaic Forest Management and three levels of government for damages caused by flooding on the band’s lands. Mosaic is the timberlands manager for TimberWest and Island Timberlands, which are owned by public pension funds.

In addition to Mosaic, the suit names the federal and provincial governments, the municipality of North Cowichan, the Island Corridor Foundation and Managed Forest Council, which is an independent provincial agency.

The Halalt reserve is home to 217 residents, many of them “multi-generational residents, using below-ground areas as living space,” according to the documents.

The Halalt First Nation says logging has aggravated flooding on its reserve and led to the destruction of local fish stocks. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The suit alleges Mosaic and other forestry defendants conducted their operations in a “careless and reckless manner” by overharvesting and failing to manage and clear harmful logging debris. It says logging caused increased surface runoff, sedimentation and riverbank erosion in the Chemainus River watershed. The plaintiffs say that has led to lost fish habitat and the “complete destruction of Halalt’s fish hatchery.”

The Halalt First Nation says logging has aggravated flooding on its reserve and led to the destruction of local fish stocks. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The suit alleges Mosaic and other forestry defendants conducted their operations in a “careless and reckless manner” by overharvesting and failing to manage and clear harmful logging debris. It says logging caused increased surface runoff, sedimentation and riverbank erosion in the Chemainus River watershed. The plaintiffs say that has led to lost fish habitat and the “complete destruction of Halalt’s fish hatchery.”

Mosaic says it takes the lawsuit “very seriously,” but declined to comment due to the matter being before the courts. The province, federal, and municipal governments, and Halalt First Nation, also declined to comment on the legal action.

The Halalt are not alone in their concerns. A provincial review of privately owned working forests has found widespread criticism of logging on private lands.

Local governments said they want private lands “managed to consider cumulative effects and better protect community watersheds,” while First Nations said private landowners are “not managing their lands to sustainable forest practices standards and they are frustrated with the lack of protection of their traditional use and spiritual sites.”

Despite the challenges, there are indications of positive change for the Chemainus.

The Cowichan Tribes, Halalt First Nation, and Cowichan Watershed Board have created the Twinned Watersheds Project, a collaborative effort aimed at improving the ecological understanding of the Chemainus and Koksilah rivers. (The Koksilah is another at-risk watercourse that flows just south of the Cowichan.)

Good chum returns in 2024 are cause for cautious optimism.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) estimates 46,000 chum returned to the Chemainus River in 2024, up from an estimated 19,000 in 2023 and just 2,000 in 2022.

Despite the improvement, those numbers are still below the 51,000 chum that returned in 2018. Officials don’t know exactly why the number of fish have declined, but they have their theories. Many blame logging practices that increase sediment in the water.

“Hopefully, with increased attention being paid to the river over the next few years we can answer some of these questions,” DFO technician Andrew Campbell said.

Video by Larry Pynn.

7. ‘It Rips Through Here’

Meanwhile, residents along the Chemainus River continue to deal with the threat of floods.

Since 2021, the province has spent millions on sediment removal, flood-barrier walls, weirs to reduce bank erosion, and disaster financial assistance to local communities along the river. But challenges remain across the watershed.

On one trip to the lower river, I visit Colin James, a farmer on the lower river who is growing old fighting for action to reduce the danger posed by floodwaters to his seven-hectare farm.

James tells me he raises beef cattle because he has no other choice.

“That’s all I can raise here. That’s because of the floods. I can’t cultivate any of the land.”

In 1988, James was interviewed and photographed for an article in the Cowichan Valley Citizen about persistent flooding. At the time, he sported a black beard. Close to four decades later, his beard is white but his spirit is undiminished.

James walks across his field and points out divots created by the rushing water.

“It rips through here,” he says. “I’ve had holes in this field big enough to lose a tractor.”

At the edge of his property, we look at a swath of riverbed where the province removed 9,000 cubic metres of gravel in 2023 to reduce the flood risk.

Colin James has called for the removal of gravel to reduce the threat of flooding to properties along the Lower Chemainus. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The problem is compounded in cases of upstream deforestation.

Colin James has called for the removal of gravel to reduce the threat of flooding to properties along the Lower Chemainus. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The problem is compounded in cases of upstream deforestation.

Colin’s neighbour, farmer Don Allingham, believes the flooding situation is getting worse on the lower Chemainus. He stands in the driveway of his 12-hectare property and holds a stack of colour photographs of the 2021 flood that reached the second bay of his barn. “I’m a lifer here — 60 years — and it’s never done that.”

Allingham’s property is located on an outside bend of the river where the flows are strongest and bite off big chunks of riverbank. Every year, the river writhes with the seasonal floods, forging news paths through the delta and leaving gravel and logs in its wake.

“It’s a violent river when it floods,” Allingham says. “Everybody wants to point their finger at Mosaic, the logging. Well, it’s always kind of flooded…but not to the degree it is now. It comes up. Boom. Like that.”

James says the removal of gravel near his property has lessened the flood threat to his farm. He would like to see gravel removed all the way downstream to the estuary.

“We don’t want to dredge the river,” he says. “We’re (talking about) removing the accumulated debris and gravel that has reduced the capacity of the river to carry water.”

But it’s not that simple.

Efforts to resolve the challenge are complex. Rivers are dynamic and constantly changing, and action taken to reduce flooding in one area can aggravate it in another spot.

Removing gravel from rivers can destroy spawning and rearing habitats for salmon, affecting the survival of eggs. It can also disrupt water flows, thereby actually increasing sedimentation in some areas. That can smother spawning beds, erode water quality, and further impact salmon.

Increasingly, humans are recognizing that simply penning in a river through ever-bigger dikes is not the panacea for flood prevention.

The Cowichan Valley Regional District has started work on a flood management plan that would bring a broader understanding of river flows and dynamics. Last year, the province published a new flood strategy that aims to reduce flood vulnerabilities by promoting local planning initiatives, like that undertaken by the regional district, and creating a “whole of government” approach to resource and land stewardship.

The strategy says that flood risks can be mitigated through better forestry practices, improved public awareness, and strategies that emphasize the preservation of natural storage areas like wetlands and undeveloped floodplains.

Video by Larry Pynn.

8. Journey’s End

Below the Halalt reserve and the impacted farms lies the Chemainus estuary — perhaps the most isolated and inaccessible stretch in the entire river system.

My years-long journey along the Chemainus River concludes on a crisp winter day with Bruce and another friend, David Carey, to paddle the quiet stretch. The river flows clear and clean at a steady pace that belies its unpredictable mood swings.

With no obvious launching site, we pull into a short driveway marked “private, no access” across the river from a historic Anglican cemetery. The landowner allows me to park my truck. I repay the kindness with my home-smoked, wild sockeye salmon.

We haul our kayaks past a gate, down an embankment beneath a steel-and-concrete bridge and onto a gravel beach.

The current carries us quickly downstream into territory where logs from past flood events are stacked high and pose a risk to navigation.

In a forested opening to our left, we spot a picnic table.

Two years ago, provincial natural resource officers investigated unauthorized wood-cutting and gravel extraction on Crown land, in addition to decades of illegal, long-term camping. A now-closed campground was fined $230.

The episode reinforces how few people travel this section of river, downstream from where most river kayakers exit the water.

Further along, the river splits and offers no obvious best route.

Paddle right and we are likely to bottom out in shallow riffles. Go left and we must choose between two narrow routes flowing amongst wood. I take my chances with a track that offers just enough water to squeeze across a submerged log.

I return safely to the main river but Bruce is not so lucky. He gets hung up on wood, his kayak tips, and into the river he spills.

Profanity bubbles to the surface as he finds himself in chilly chest-deep water.

David and I collect Bruce’s kayak and gear floating downriver and regroup on a stretch of gravel where we share spare clothing and have lunch.

Bald eagles watch from big cottonwoods as we remove metres of string that could ensnare wildlife such as river otters and birds. It’s possible the string washed downstream in high water from a construction site.

As we continue our paddle, trees fall away and the braided estuary begins.

The area provides critical habitat for juvenile salmon, waterfowl and migratory birds.

Ducks Unlimited purchased 210 hectares in the lower river from the owners of the Crofton pulp mill in 2009. The organization also has an agreement with local farmers to raise crops such as corn and hay on close to 30 hectares to benefit waterfowl and other migratory birds.

Birdwatchers like Liam Ragan, a local co-ordinator for Important Bird Areas Canada, conduct an annual count of birds just after Christmas near the estuary. Last year they recorded 606 birds representing 24 species — including 163 bufflehead and 127 common goldeneye.

“From a birdwatching perspective, there’s a ton of untapped potential for what’s going on in there,” Ragan told me.

As the Chemainus approaches the ocean, its waters slow and form the basis for a large wetland that provides ideal habitat for dozens of bird species. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The estuary remains good habitat for birds partly because humans can’t easily traverse it. You can’t walk across the marsh. The relentless goo would take you down. Only small craft like ours can navigate it — and only then at high tide.

As the Chemainus approaches the ocean, its waters slow and form the basis for a large wetland that provides ideal habitat for dozens of bird species. Photo by Larry Pynn.

The estuary remains good habitat for birds partly because humans can’t easily traverse it. You can’t walk across the marsh. The relentless goo would take you down. Only small craft like ours can navigate it — and only then at high tide.

Two dozen harbour seals provide an escort as we paddle toward the throbbing smoke stacks of Crofton mill and the town’s boat launch.

The moment provides opportunity for reflection.

I have described the Chemainus as a forgotten river. My travels through the watershed from top to bottom have only reinforced that opinion.

But I refuse to believe it is a lost river.

The Chemainus remains a place where ancient trees grow in a small primeval forest, where waters still stir with a chinook run’s last survivors, and where birdlife thrives in a secluded estuary largely hidden from the world.

One must leave with a sense of hope, as long as the fight for existence continues. ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/design-article.thetyee.ca/ui/img/yellowblob.png)