Culture

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski is very pregnant and very far away from the nearest hospital. An excerpt from ‘Wilderness Mother.’

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski TodayThe Tyee

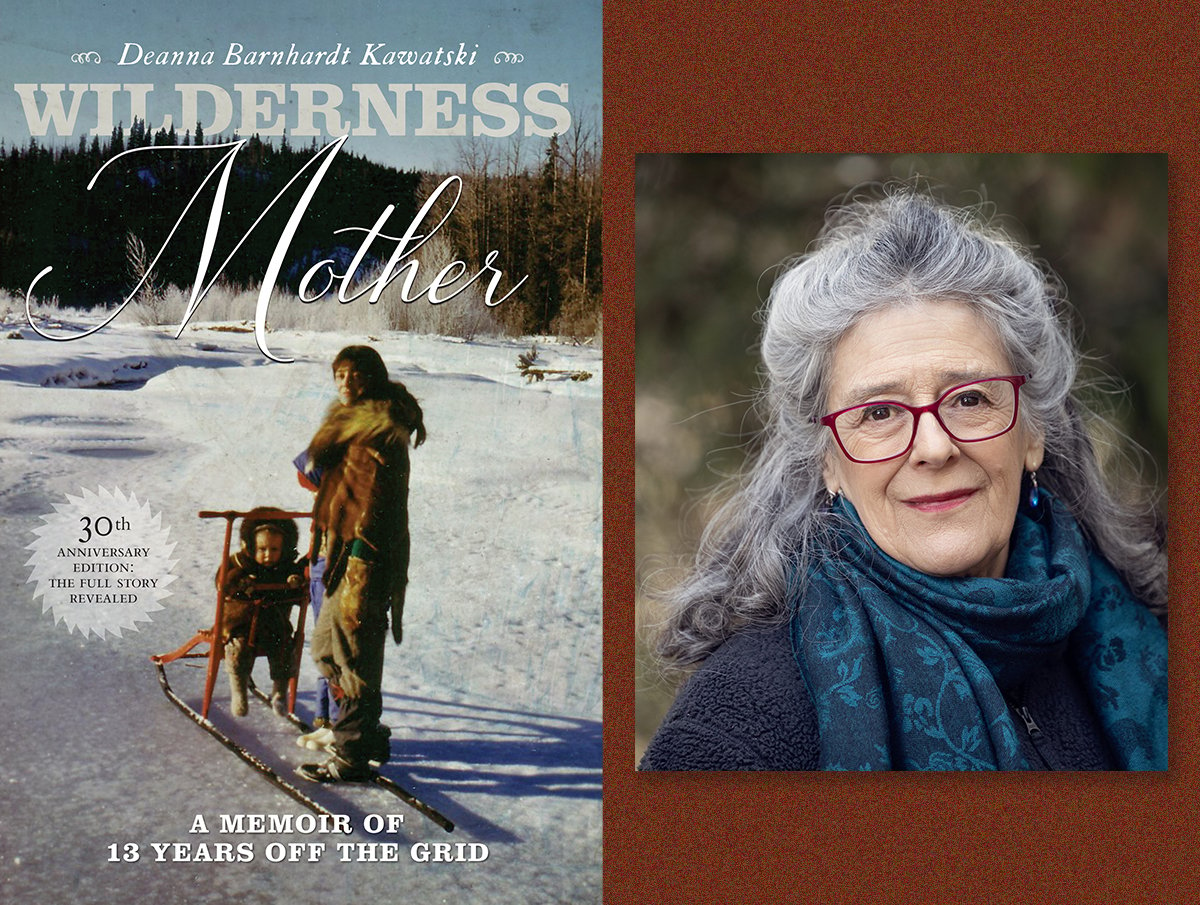

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski is the author of nine books, including the recently re-released Wilderness Mother: A Memoir of 13 Years Off the Grid.

[Editor’s note: ‘Wilderness Mother: A Memoir of 13 Years off the Grid,’ originally published in 1995, has recently been republished by Ronsdale Press to celebrate the book’s 30th anniversary. In ‘Wilderness Mother,’ Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski recounts how she met her hermit husb…

Culture

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski is very pregnant and very far away from the nearest hospital. An excerpt from ‘Wilderness Mother.’

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski TodayThe Tyee

Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski is the author of nine books, including the recently re-released Wilderness Mother: A Memoir of 13 Years Off the Grid.

[Editor’s note: ‘Wilderness Mother: A Memoir of 13 Years off the Grid,’ originally published in 1995, has recently been republished by Ronsdale Press to celebrate the book’s 30th anniversary. In ‘Wilderness Mother,’ Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski recounts how she met her hermit husband, Jay, in the late 1970s while working at a fire tower in northern B.C. For the next 13 years, Kawatski led an alternately peaceful and tumultuous off-grid life with Jay — raising two kids, growing and hunting their own food, building their own shelter. In this excerpt, a very pregnant Barnhardt Kawatski goes into labour with her first child.]

Author photo by Janis Smith Photography.

Author photo by Janis Smith Photography.

My due date, June 15, came and went. Jay and I were both restless and I grew moody and depressed, plagued by the usual insecurities about a home birth. What if something went wrong? What if the baby died? Would I be strong enough to shoulder the blame? I could face my own death, but surely the death of my child would be too much to bear. Then I calmed as I reasoned that babies also die in hospitals, that life never comes with guarantees. Intuitively I knew that at home was where our baby was meant to enter the world and that everything would be okay.

It hadn’t rained for weeks and we were concerned about our garden in the Ningunsaw Valley. At this crucial stage of pregnancy, I didn’t want to be on my own while Jay travelled on foot to look after the crops. So on June 18 we trudged together to the valley. Through the afternoon and far into the evening we toiled, thinning and weeding, then packing water to the orderly rows of vegetables. Later, outside the unfinished cabin, I wearily prepared us a moose stew on the firepit that was closed in with an old cast-iron stovetop. Famished from the exertion, we eagerly sat down to our simple supper, but as we did so I discovered that my tailbone was extremely tender. I couldn’t find a comfortable position to sit in. Even though Jay manoeuvred the best stump over for me to perch on, its stubborn surface caused me greater discomfort than before.

We and several hundred mosquitoes spent a restless night on loose boards in the rough loft. The next day the sun beat down on us as I thinned beets and Jay watered. As my fingers sank into the rich, moist soil, I did my best to ignore the stinging insects and tried to revel in the sights and sounds of spring. The baby green leaves of elderberry, alder, poplar, birch and cottonwood had unfurled to their full glory. Tiny winter wrens with their gigantic songs perched on alder branches while tuxedoed robins skittered across the garden. They joined the chorus of scores of songbirds while a male ruffed grouse, just beyond the clearing, accompanied them with drumming. But I was now finding it difficult to move from row to row, and I also felt a strong urge to sleep.

A half hour later Jay and I ventured out to the river to rest and escape the insects, which preferred the woods to the open, windswept river flat. As we broke out of the timber we spotted two mountain bluebirds flickering through the alder like tiny pieces of fallen sky. Then we stretched out onto the warm black sand and began to take turns reading aloud from Great Expectations. The irony of our choice of book was not lost on me.

Suddenly I was seized with the realization that we had no time to spare. We had to set out for our cabin on Desiré Lake immediately. I had no wish to give birth in our sketchy home in the valley. It took mere minutes to pack and set out.

The first lung-bursting hill we had to climb was a 50-degree slope with a rise of sixty metres. It was like toiling up twenty consecutive flights of stairs. Mosquitoes clung to the undersides of thimbleberry leaves, then flew forth in ever-swelling battalions to attack us. Through their ranks wafted the aroma of cottonwood leaves, and I glanced at the mosaic of treetops against an indigo sky. Although even in my state I was accustomed to 16-kilometre hikes, at the top of the hill my calves ached and my upper body trembled.

After plodding to the summit of the next 30-metre rise, I felt a sudden gush of warm liquid down my legs. The amniotic membrane had burst! It was 5 p.m. and my contractions began instantly. I had four kilometres of rugged trail yet to go.

Jay put his hand gently on my back. “You can do it,” he encouraged, wiping more insect repellent the length of my arms. The insects now surrounded me in screaming masses. After my water broke, thousands of bloodthirsty mosquitoes were magnetically drawn to me. It took every ounce of my concentration to focus on my breathing during the contractions as the bugs invaded my eyes, ears, nose and throat. All I could hear was their sanity-shredding whine.

Jay tried to reassure me. “You have lots of time and energy.”

I turned to him. “I’ll tell you one thing,” I vowed. “There’s no damned way I’m going to give birth out here!”

Storms of orange and black butterflies released themselves with every step I took on the path ahead. Flickering by our heads, they competed with the whining mosquitoes for space, chaperoning us through the birch and balsam. I had never seen so many in one place, and their presence gave me fresh hope — a signal of my metamorphosis as a mother.

But the trail remained an obstacle course of windfalls, steep hills and boot-sucking bogs. Two hours later, filthy and exhausted, we reached the cabin. My wet pants were thick with mud from the knees down and my face and arms were smeared with repellent, sweat and squished mosquitoes.

l kicked off my gumboots and kneeled on the floor, preparing for another contraction. Jay flew into activity. He lit the fire, hauled water in buckets from the creek, heated it, fed the animals and threw together a dinner of beet greens, spinach, lettuce, scrambled eggs and raspberry leaf tea. Between bites, I had to drop to the floor on all fours, the position in which I felt least uncomfortable and better able to cope with the contractions.

Excerpted from ‘Wilderness Mother: A Memoir of 13 Years Off the Grid’ by Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski. Copyright © 2025 Deanna Barnhardt Kawatski. Published by Ronsdale Press. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved. ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/design-article.thetyee.ca/ui/img/yellowblob.png)

- Share:

- **

Get The Tyee’s Daily Catch, our free daily newsletter.

** The Barometer

What Do You Think of PM Carney’s First Months?

-

I’m still excited about PM Carney.

-

His shine has worn off for me.

-

I never liked the guy.

-

I don’t know.

-

Tell us more…